Author: Sjir Hoeijmakers, Msc Last Updated 05/2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evidence-Based Policy Cause Area Report

Evidence-Based Policy Cause Area Report AUTHOR: 11/18 MARINELLA CAPRIATI, DPHIL 1 — Founders Pledge Animal Welfare Executive Summary By supporting increased use of evidence in the governments of low- and middle-income countries, donors can dramatically increase their impact on the lives of people living in poverty. This report explores how focusing on evidence-based policy provides an opportunity for leverage, and presents the most promising organisation we identified in this area. A high-risk/high-return opportunity for leverage In the 2013 report ‘The State of the Poor’, the World Bank reported that, as of 2010, roughly 83% of people in extreme poverty lived in countries classified as ‘lower-middle income’ or below. By far the most resources spent on tackling poverty come from local governments. American think tank the Brookings Institution found that, in 2011, $2.3 trillion of the $2.8 trillion spent on financing development came from domestic government revenues in the countries affected. There are often large differences in the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of social programs— the amount of good done per dollar spent can vary significantly across programs. Employing evidence allows us to identify the most cost-effective social programs. This is useful information for donors choosing which charity to support, but also for governments choosing which programs to implement, and how. This suggests that employing philanthropic funding to improve the effectiveness of policymaking in low- and middle-income countries is likely to constitute an exceptional opportunity for leverage: by supporting the production and use of evidence in low- and middle-income countries, donors can potentially enable policy makers to implement more effective policies, thereby reaching many more people than direct interventions. -

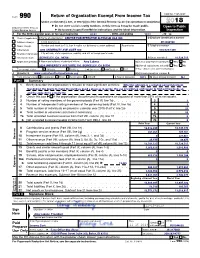

2018 ▶ Do Not Enter Social Security Numbers on This Form As It May Be Made Public

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) 2018 ▶ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Open to Public Internal Revenue Service ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information. Inspection A For the 2018 calendar year, or tax year beginning01/01 , 2018, and ending12/31 , 20 18 B Check if applicable: C Name of organization CENTRE FOR EFFECTIVE ALTRUISM USA INC D Employer identification number Address change Doing business as 47-1988398 Name change Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial return 2054 UNIVERSITY AVE SUITE 300 510-725-1395 Final return/terminated City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code Amended return BERKELEY, CA, 94704 G Gross receipts $ 10,524,715 Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: Amy Labenz H(a) Is this a group return for subordinates? Yes ✔ No 2054 UNIVERSITY AVE SUITE 300, BERKELEY, CA 94704 H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: ✔ 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( ) ◀ (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If “No,” attach a list. (see instructions) J Website: ▶ www.centerforeffectivealtruism.org H(c) Group exemption number ▶ K Form of organization: ✔ Corporation Trust Association Other ▶ L Year of formation: 2013 M State of legal domicile: NJ Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission or most significant activities: Effective altruism is a growing social movement founded on the desire to make the world as good a place as it can be, the use of evidence and reason to find out how to do so, and the audacity to actually try. -

Climate Change Cause Area Report

Climate Change Cause Area Report AUTHOR: LAST UPDATED 05/2018 JOHN HALSTEAD, DPHIL Executive Summary Climate change is an unprecedented problem requiring unprecedented global cooperation. However, global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have failed thus far. This report discusses the science, politics, and economics of climate change, and what philanthropists can do to help improve progress on tackling climate change. 1. The climate challenge and progress so far The first section provides an overview of the science of climate change, what needs to be done in order to avoid dangerous warming, and progress so far. One can mark the advent of the Industrial Revolution with James Watt’s patent for the steam engine in 1769. Until that point, for most of human history concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere had hovered around 280 parts per million (ppm). They recently passed 400 ppm for the first time in hundreds of thousands of years. This has been driven by the massive increase in deforestation and the burning of fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution. CO2 and other greenhouse gases, such as methane, remain in the atmosphere and trap some of the heat leaving the planet, causing global warming. The metric of CO2-equivalent (CO2e) expresses the warming effect of all greenhouse gases in terms of the warming effect of CO2. The challenge facing humanity is not to reduce emissions rates to a lower level: if emissions continue at a constant (even low) positive rate, atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gas concentrations will continue to increase and so will global temperatures. -

Farm Animal Funders Briefings

BRIEFING SERIES February, 2019 v1.0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Smart Giving: Some Fundamentals 2 Supporting Alternative Foods To Farmed Animal Products 4 Veg Advocacy 7 Corporate Campaigns For Welfare Reforms 9 Fishes 12 Legal and Legislative Methods 13 A Global Perspective on Farmed Animal Advocacy 15 Shallow Review: Increasing Donations Through Your Donation 19 2 Smart Giving: Some Fundamentals How Much To Give? There are a number of approaches to how much to give, Why Give? including: For the world: There are over 100 hundred billion farmed animals alive at any moment in conditions that Giving what you don’t need cause severe suffering, that number has been increasing over time and is projected to continue to do so. Consuming animal products is associated with many x % Pledging a set percentage negative health outcomes and animal agriculture is a chief cause of environmental degradation—causing approximately 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions. % Giving to reach a personal best For you: Giving activates the brain’s reward centers, Some people give everything above what is necessary to resulting in increased life satisfaction and happiness. satisfy their needs, in part because of evidence that high levels of income have diminishing returns on wellbeing. How Can We Help Identify Cost-effective Funding Thousands of people (including some of the wealthiest) How To Give? Opportunities? publicly pledge some set percentage for giving. Pledging could increase your commitment to giving, further Effective giving is important because top Farmed Animal Funders release briefings and research connect you with a giving community, and inspire others. giving options are plausibly many times more different promising areas. -

Risks of Space Colonization

Risks of space colonization Marko Kovic∗ July 2020 Abstract Space colonization is humankind's best bet for long-term survival. This makes the expected moral value of space colonization immense. However, colonizing space also creates risks | risks whose potential harm could easily overshadow all the benefits of humankind's long- term future. In this article, I present a preliminary overview of some major risks of space colonization: Prioritization risks, aberration risks, and conflict risks. Each of these risk types contains risks that can create enormous disvalue; in some cases orders of magnitude more disvalue than all the potential positive value humankind could have. From a (weakly) negative, suffering-focused utilitarian view, we there- fore have the obligation to mitigate space colonization-related risks and make space colonization as safe as possible. In order to do so, we need to start working on real-world space colonization governance. Given the near total lack of progress in the domain of space gover- nance in recent decades, however, it is uncertain whether meaningful space colonization governance can be established in the near future, and before it is too late. ∗[email protected] 1 1 Introduction: The value of colonizing space Space colonization, the establishment of permanent human habitats beyond Earth, has been the object of both popular speculation and scientific inquiry for decades. The idea of space colonization has an almost poetic quality: Space is the next great frontier, the next great leap for humankind, that we hope to eventually conquer through our force of will and our ingenuity. From a more prosaic point of view, space colonization is important because it represents a long-term survival strategy for humankind1. -

References: ACE's 2020 Review Of

References ACE’s 2020 Review of Environment & Animal Society of Taiwan Animal Charity Evaluators. (n.d.). ACE Movement Grants. Retrieved November 7, 2020, from https://animalcharityevaluators.org/donation-advice/ace-movement-grants/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2016). Why Farmed Animals? https://animalcharityevaluators.org/donation-advice/why-farmed-animals/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2017). Prioritizing Causes. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/advocacy-interventions/prioritizing-causes/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2018a). Allocation of Movement Resources. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/research/other-topics/allocation-of-movement-resourc es/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2018b). Subjective Confidence Intervals. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/research/methodology/subjective-confidence-interval/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2019). Interventions. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/advocacy-interventions/interventions/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2020a). 2019 Giving Metrics Report. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/about/impact/giving-metrics/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2020b). Cause Priorities for ACE. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/advocacy-interventions/prioritizing-causes/causes-we- consider/ Animal Charity Evaluators. (2020c). Menu of Outcomes for Animal Advocacy. https://animalcharityevaluators.org/research/methodology/menu-of-outcomes/ Animal Welfare Institute. (n.d.). International Shark Finning Bans and Policies. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://awionline.org/content/international-shark-finning-bans-and-policies -

Peter Singer's Effective Altruism

Peter Singer’s effective altruism By Stephen Howes Earlier this year, Peter Singer was in Melbourne to address the 2016 Australian Effective Altruism Conference. I was also there to speak at the same conference, to find out more about this new and growing movement, and to talk to Peter Singer, its founder. Our story starts in 1970. The essay A refugee mother and child from East Bengal during the Bangladesh war, in 1971. Photo: Sunil Janah In 1970, what was then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) was hit by a cyclone that killed half a million people. In 1971, war broke out between East and West Pakistan, leading to Bangladesh’s independence, and displacing nearly ten million refugees. The West was shocked and moved. George Harrison and Ravi Shankar organised The Concert for Bangladesh, the first of the big benefit concerts. Peter Singer, then a young philosophy lecturer at Oxford University, wrote an essay “Famine, Affluence and Morality”, which was published in 1972 in the academic journal Philosophy and Public Affairs. Singer’s argument consisted of two basic propositions. The first is the duty to prevent suffering. Singer expressed the more moderate version of this as a requirement to “prevent bad occurrences unless, to do so, we have to sacrifice something morally significant.” The second is the moral irrelevance of distance. “It makes no difference whether the person I can help is a neighbour’s child ten yards away from me or a Bengali whose name I shall never know, ten thousand miles away.” It was a compelling one-two. To drive his point home, Singer used the parable of a child drowning in a shallow pool. -

J.Savoie,K.Sarek,October2019

J. Savoie, K. Sarek, October 2019 Animal Research Page 2 Scope of the research and description of the approach: Using research is a meta-approach aimed at helping animal organizations, activists, and donors do more good in the long term. There are numerous ways of performing research to benefit animals, and many organizations are working on different components. Conducting and publicizing research results can inform decision-makers, making research impactful through translating it into concrete action and change. Research can vary from empirical, such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on online ads, to softer research, such as examining crucial considerations that might affect the animal movement. The main areas we considered were: Animal Ask Institute Funder-directed research Animal research agenda creation Randomized controlled trials for animal issues Deeper intervention reports Macro data research Impact evaluations for animal organizations Hiring a research organization (internal to the animal advocacy movement) Hiring a research organization (external to the movement) Research on other movements Field establishment research Cross-cutting animal research Gene-modification research Tools of research Charity evaluation research Creating a research database Throughout this report, we consider crucial considerations that cut across different types of research. We dive deeper into each of these possibilities using a number of methods, including expert interviews, to eventually narrow down the most promising approaches for a new research organization. Page 3 Crucial considerations Remaining crucial considerations affecting this area How will research be applied to decision-making? Funders, particularly more EA-aligned ones, seem more open to using research in their decisions than they have been in the past. -

Annual Report

2020 ANNUAL REPORT www.rcforward.org A Letter from Our Executive Director Our team is humbled that even in the midst of a global Although this growth certainly warrants celebration, we pandemic, hundreds of people across Canada collectively remain committed to adding partner charities only with donated $2.7 million dollars to high-impact charities. good reason. Our partner charities featured on rcforward.org/donate are recommended or endorsed by By donating through our effective giving platform, RC renowned charity evaluators like GiveWell, Animal Charity Forward, they had the opportunity to amplify their impact Evaluators, EA Funds, Open Philanthropy, Founders Pledge, by unlocking tax-efficient giving options. In what may be and The Life You Can Save. the most exciting part of filing Canadian income taxes, charitable tax credits can be worth up to 50% of the Additionally, our team and the donors we support were amount donated! RC Forward remains the only way for compelled to respond to 2020’s extraordinary events, while Canadians to donate tax efficiently (and therefore, cost remaining committed to the principles of effective giving. effectively) to virtually all of the high-impact charities we Through two special initiatives, we offered donors options partner with. to tax-efficiently support select organizations addressing the COVID-19 pandemic and criminal justice reform. When we launched RC Forward at the end of 2017, we could not have imagined that less than four years later, Whether you’re a donor who gives with RC Forward, a Canadians would have leveraged it to give over $9 million partner charity, or a funder who helps cover the platform’s to the high-impact charities featured on the platform. -

Mental Health Cause Area Report

Mental Health Cause Area Report AUTHORS: JAMES SNOWDEN, MSC, LAST UPDATED: 02/19 JOHN HALSTEAD, DPHIL, SJIR HOEIJMAKERS MSC Glossary CBT Cognitive Behavioural A form of talking psychotherapy Therapy DALY Disability-Adjusted Life A composite measure of morbidity and mortality caused by a Year disease DSM Diagnostic and Statistical Standard classification of mental disorders used by mental Manual of Mental Disorders health professionals IPT-G Interpersonal Group IPT delivered in a group setting Therapy MHF Mental Health Facilitator Community members given brief specialised training in delivery of mental health interventions MNS Mental health, A group of disorders which affect the mind Neurological and Substance use disorders PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire used to monitor severity of depression and Questionnaire response to treatment RCT Randomised Controlled A study design which includes a randomised control group. Trial Often considered the gold standard of evidence 1 — Founders Pledge Mental Health Executive Summary1 1. Mental health Mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety, and dementia are a daily reality of suffering for millions of people across the world. In total, mental health, neurological and substance-abuse (MNS) disorders account for 10.5% of the global disease burden, second only to cardiovascular disease. In addition to their health and wellbeing costs, MNS disorders impose a large economic cost: a 2012 report estimated the annual global cost of mental health conditions at $2.5 trillion. Lastly, there is still a large stigma on mental health: those suffering from mental health problems often face marginalisation at both the social and institutional level. 2. Our process Our research produced three key findings, which helped to guide our search for impactful charities: 1. -

Research Report Health Development Policy

GROWTH POLCY PRMARY AUTHOR: A. LADAK Review: K. Sarek, E. Hausen OCTOBER 2020 CONSDERED CE Research Report: Health & Development Policy - Growth Policy, 2020 Page 2 Research Report: Health & Development Policy – Growth Policy (2020 Considered Idea) Primary author: Ali Ladak Review: Karolina Sarek & Erik Hausen Date of publication: October 2020 Research period: 2020 This is a summary report about growth policy. Due to its low probability of success, we do not recommend this intervention despite its potential to be highly cost-effective. Thanks to Karolina Sarek and Erik Hausen for reviewing the research, and to Joe Benton, Antonia Shann, Fin Moorhouse, and Urszula Zarosa for their contributions to this report. We are also grateful to the six experts who took the time to offer their thoughts on this research. For questions about the content of this research please contact Ali Ladak at [email protected]. For questions about the research process, charity recommendations, and intervention comparisons please contact Karolina Sarek at [email protected]. Charity Entrepreneurship is a research and training program that incubates multiple high-impact charities annually. Our mission is to cause more effective charities to exist in the world by connecting talented individuals with high-impact intervention opportunities. We achieve this through an extensive research process and through our Incubation Program. CE Research Report: Health & Development Policy - Growth Policy, 2020 Page 3 Research Process Before opening the report, we think it is important to introduce our research process. Knowing the principles of the process helps readers understand how we formed our conclusions and enables greater reasoning transparency. -

GHD Prospectus Draft 1

Global Health and Development Fund Supporting highly-impactful, evidence-based, and neglected solutions to the global challenges of poverty and inequality. Solving a Global Problem Despite substantial progress in recent decades on development goals, nearly half the world lives on less than $2.50 per day. This poverty leads to a huge amount of hardship and unnecessary loss of life. In 2019, more than five million children under five years old died, mostly from preventable causes like diarrhoea, malaria, and respiratory infections. Poverty is also associated with hunger, exposure to conflict, and limited access to education and other opportunities. We believe that all individuals, regardless of where they were born, deserve the chance to live happy, healthy, and prosperous lives. Global inequality in mortality, health, poverty and more is a tragic, but not unsolvable, problem. Researchers, advocates, and organisations around the world are working to scale up solutions to these problems. By taking a thoughtful, evidence-based approach to philanthropy that accelerates the best of these solutions, we can do immense good. Jonathan Torgovnik/Getty Images/Images of Empowerment Meet the Fund Managers Sam Carter is a Research Advisor based in New York. Sam previously worked at MIT’s Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), where she led global policy outreach on cash transfers and financial inclusion, and supported government scale-ups of evidence-based programmes. Sam has a Master’s degree in International Economics from Johns Hopkins University. She has also worked at the World Bank and numerous organisations in the U.S., Bolivia, Indonesia, and Peru. Stephen Clare is an Applied Researcher based in London.