To Effective Philanthropy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effective Altruism William Macaskill and Theron Pummer

1 Effective Altruism William MacAskill and Theron Pummer Climate change is on course to cause millions of deaths and cost the world economy trillions of dollars. Nearly a billion people live in extreme poverty, millions of them dying each year of easily preventable diseases. Just a small fraction of the thousands of nuclear weapons on hair‐trigger alert could easily bring about global catastrophe. New technologies like synthetic biology and artificial intelligence bring unprece dented risks. Meanwhile, year after year billions and billions of factory‐farmed ani mals live and die in misery. Given the number of severe problems facing the world today, and the resources required to solve them, we may feel at a loss as to where to even begin. The good news is that we can improve things with the right use of money, time, talent, and effort. These resources can bring about a great deal of improvement, or very little, depending on how they are allocated. The effective altruism movement consists of a growing global community of peo ple who use reason and evidence to assess how to do as much good as possible, and who take action on this basis. Launched in 2011, the movement now has thousands of members, as well as influence over billions of dollars. The movement has substan tially increased awareness of the fact that some altruistic activities are much more cost‐effective than others, in the sense that they do much more good than others per unit of resource expended. According to the nonprofit organization GiveWell, it costs around $3,500 to prevent someone from dying of malaria by distributing bed nets. -

Evidence-Based Policy Cause Area Report

Evidence-Based Policy Cause Area Report AUTHOR: 11/18 MARINELLA CAPRIATI, DPHIL 1 — Founders Pledge Animal Welfare Executive Summary By supporting increased use of evidence in the governments of low- and middle-income countries, donors can dramatically increase their impact on the lives of people living in poverty. This report explores how focusing on evidence-based policy provides an opportunity for leverage, and presents the most promising organisation we identified in this area. A high-risk/high-return opportunity for leverage In the 2013 report ‘The State of the Poor’, the World Bank reported that, as of 2010, roughly 83% of people in extreme poverty lived in countries classified as ‘lower-middle income’ or below. By far the most resources spent on tackling poverty come from local governments. American think tank the Brookings Institution found that, in 2011, $2.3 trillion of the $2.8 trillion spent on financing development came from domestic government revenues in the countries affected. There are often large differences in the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of social programs— the amount of good done per dollar spent can vary significantly across programs. Employing evidence allows us to identify the most cost-effective social programs. This is useful information for donors choosing which charity to support, but also for governments choosing which programs to implement, and how. This suggests that employing philanthropic funding to improve the effectiveness of policymaking in low- and middle-income countries is likely to constitute an exceptional opportunity for leverage: by supporting the production and use of evidence in low- and middle-income countries, donors can potentially enable policy makers to implement more effective policies, thereby reaching many more people than direct interventions. -

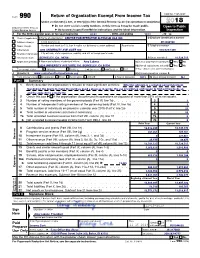

2018 ▶ Do Not Enter Social Security Numbers on This Form As It May Be Made Public

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) 2018 ▶ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Open to Public Internal Revenue Service ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information. Inspection A For the 2018 calendar year, or tax year beginning01/01 , 2018, and ending12/31 , 20 18 B Check if applicable: C Name of organization CENTRE FOR EFFECTIVE ALTRUISM USA INC D Employer identification number Address change Doing business as 47-1988398 Name change Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial return 2054 UNIVERSITY AVE SUITE 300 510-725-1395 Final return/terminated City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code Amended return BERKELEY, CA, 94704 G Gross receipts $ 10,524,715 Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: Amy Labenz H(a) Is this a group return for subordinates? Yes ✔ No 2054 UNIVERSITY AVE SUITE 300, BERKELEY, CA 94704 H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: ✔ 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( ) ◀ (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If “No,” attach a list. (see instructions) J Website: ▶ www.centerforeffectivealtruism.org H(c) Group exemption number ▶ K Form of organization: ✔ Corporation Trust Association Other ▶ L Year of formation: 2013 M State of legal domicile: NJ Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission or most significant activities: Effective altruism is a growing social movement founded on the desire to make the world as good a place as it can be, the use of evidence and reason to find out how to do so, and the audacity to actually try. -

By William Macaskill

Published on June 20, 2016 Brother, can you spare an RCT? ‘Doing Good Better’ by William MacAskill By Terence Wood If you’ve ever thought carefully about international development you will be tormented by shoulds. Should the Australian government really give aid rather Link: https://devpolicy.org/brother-can-spare-util-good-better-william-macaskill-20160620/ Page 1 of 5 Date downloaded: September 30, 2021 Published on June 20, 2016 than focus on domestic poverty? Should I donate more money personally? And if so, what sort of NGO should I give to? The good news is that William MacAskill is here to help. MacAskill is an associate professor in philosophy at the University of Oxford, and in Doing Good Better he wants to teach you to be an Effective Altruist. Effective Altruism is an attempt to take a form ofconsequentialism (a philosophical viewpoint in which an action is deemed right or wrong on the basis of its consequences) and plant it squarely amidst the decisions of our daily lives. MacAskill’s target audience isn’t limited to people involved in international development, but almost everything he says is relevant. Effective Altruists contend we should devote as much time and as many resources as we reasonably can to help those in greater need. They also want us to avoid actions that cause, or will cause, suffering. Taken together, this means promoting vegetarianism, (probably) taking action on climate change, and–of most interest to readers of this blog–giving a lot of aid. That’s the altruism. As for effectiveness, MacAskill argues that when we give we need to focus on addressing the most acute needs, while carefully choosing what works best. -

Wise Leadership & AI 3

Wise Leadership and AI Leadership Chapter 3 | Behind the Scenes of the Machines What’s Ahead For Artificial General Intelligence? By Dr. Peter VERHEZEN With the AMROP EDITORIAL BOARD Putting the G in AI | 8 points True, generalized intelligence will be achieved when computers can do or learn anything that a human can. At the highest level, this will mean that computers aren’t just able to process the ‘what,’ but understand the ‘why’ behind data — context, and cause and effect relationships. Even someday chieving consciousness. All of this will demand ethical and emotional intelligence. 1 We underestimate ourselves The human brain is amazingly general compared to any digital device yet developed. It processes bottom-up and top-down information, whereas AI (still) only works bottom-up, based on what it ‘sees’, working on specific, narrowly defined tasks. So, unlike humans, AI is not yet situationally aware, nuanced, or multi-dimensional. 2 When can we expect AGI? Great minds do not think alike Some eminent thinkers (and tech entrepreneurs) see true AGI as only a decade or two away. Others see it as science fiction — AI will more likely serve to amplify human intelligence, just as mechanical machines have amplified physical strength. 3 AGI means moving from homo sapiens to homo deus Reaching AGI has been described by the futurist Ray Kurzweil as ‘singularity’. At this point, humans should progress to the ‘trans-human’ stage: cyber-humans (electronically enhanced) or neuro-augmented (bio-genetically enhanced). 4 The real risk with AGI is not malice, but unguided brilliance A super-intelligent machine will be fantastically good at meeting its goals. -

Letters to the Editor

Articles Letters to the Editor Research Priorities for is a product of human intelligence; we puter scientists, innovators, entrepre - cannot predict what we might achieve neurs, statisti cians, journalists, engi - Robust and Beneficial when this intelligence is magnified by neers, authors, professors, teachers, stu - Artificial Intelligence: the tools AI may provide, but the eradi - dents, CEOs, economists, developers, An Open Letter cation of disease and poverty are not philosophers, artists, futurists, physi - unfathomable. Because of the great cists, filmmakers, health-care profes - rtificial intelligence (AI) research potential of AI, it is important to sionals, research analysts, and members Ahas explored a variety of problems research how to reap its benefits while of many other fields. The earliest signa - and approaches since its inception, but avoiding potential pitfalls. tories follow, reproduced in order and as for the last 20 years or so has been The progress in AI research makes it they signed. For the complete list, see focused on the problems surrounding timely to focus research not only on tinyurl.com/ailetter. - ed. the construction of intelligent agents making AI more capable, but also on Stuart Russell, Berkeley, Professor of Com - — systems that perceive and act in maximizing the societal benefit of AI. puter Science, director of the Center for some environment. In this context, Such considerations motivated the “intelligence” is related to statistical Intelligent Systems, and coauthor of the AAAI 2008–09 Presidential Panel on standard textbook Artificial Intelligence: a and economic notions of rationality — Long-Term AI Futures and other proj - Modern Approach colloquially, the ability to make good ects on AI impacts, and constitute a sig - Tom Dietterich, Oregon State, President of decisions, plans, or inferences. -

Climate Change Cause Area Report

Climate Change Cause Area Report AUTHOR: LAST UPDATED 05/2018 JOHN HALSTEAD, DPHIL Executive Summary Climate change is an unprecedented problem requiring unprecedented global cooperation. However, global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have failed thus far. This report discusses the science, politics, and economics of climate change, and what philanthropists can do to help improve progress on tackling climate change. 1. The climate challenge and progress so far The first section provides an overview of the science of climate change, what needs to be done in order to avoid dangerous warming, and progress so far. One can mark the advent of the Industrial Revolution with James Watt’s patent for the steam engine in 1769. Until that point, for most of human history concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere had hovered around 280 parts per million (ppm). They recently passed 400 ppm for the first time in hundreds of thousands of years. This has been driven by the massive increase in deforestation and the burning of fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution. CO2 and other greenhouse gases, such as methane, remain in the atmosphere and trap some of the heat leaving the planet, causing global warming. The metric of CO2-equivalent (CO2e) expresses the warming effect of all greenhouse gases in terms of the warming effect of CO2. The challenge facing humanity is not to reduce emissions rates to a lower level: if emissions continue at a constant (even low) positive rate, atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gas concentrations will continue to increase and so will global temperatures. -

194 William Macaskill. Doing Good Better: How Effective Altruism Can Help You Help Others, Do Work That Matters, and Make Smarte

Philosophy in Review XXXIX (November 2019), no. 4 William MacAskill. Doing Good Better: How Effective Altruism Can Help You Help Others, Do Work that Matters, and Make Smarter Choices About Giving Back. Avery 2016. 272 pp. $17.00 USD (Paperback ISBN 9781592409662). Will MacAskill’s Doing Good Better provides an introduction to the Effective Altruism movement, and, in the process, it makes a strong case for its importance. The book is aimed at a general audience. It is fairly short and written for the most part in a light, conversational tone. Doing Good Better’s only real rival as a treatment of Effective Altruism is Peter Singer’s The Most Good You Can Do, though MacAskill’s and Singer’s books are better seen as companion pieces than rivals. Like The Most Good You Can Do, Doing Good Better offers the reader much of philosophical interest, and it delivers novel perspectives and even some counterintuitive but well-reasoned conclusions that will likely provoke both critics and defenders of Effective Altruism for some time to come. Before diving into Doing Good Better we want to take a moment to characterize Effective Altruism. Crudely put, Effective Altruists are committed to three claims. First, they maintain that we have strong reason to help others. Second, they claim that these reasons are impartial in nature. And, third, they hold that we are required to act on these reasons in the most effective manner possible. Hence, according to Effective Altruists, those of us who are fortunate enough to have the leisure to write (or read) scholarly book reviews (1) should help those who are most in need, (2) should do so even if we lack any personal connection to them, and (3) should do so as efficiently as we can. -

Farm Animal Funders Briefings

BRIEFING SERIES February, 2019 v1.0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Smart Giving: Some Fundamentals 2 Supporting Alternative Foods To Farmed Animal Products 4 Veg Advocacy 7 Corporate Campaigns For Welfare Reforms 9 Fishes 12 Legal and Legislative Methods 13 A Global Perspective on Farmed Animal Advocacy 15 Shallow Review: Increasing Donations Through Your Donation 19 2 Smart Giving: Some Fundamentals How Much To Give? There are a number of approaches to how much to give, Why Give? including: For the world: There are over 100 hundred billion farmed animals alive at any moment in conditions that Giving what you don’t need cause severe suffering, that number has been increasing over time and is projected to continue to do so. Consuming animal products is associated with many x % Pledging a set percentage negative health outcomes and animal agriculture is a chief cause of environmental degradation—causing approximately 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions. % Giving to reach a personal best For you: Giving activates the brain’s reward centers, Some people give everything above what is necessary to resulting in increased life satisfaction and happiness. satisfy their needs, in part because of evidence that high levels of income have diminishing returns on wellbeing. How Can We Help Identify Cost-effective Funding Thousands of people (including some of the wealthiest) How To Give? Opportunities? publicly pledge some set percentage for giving. Pledging could increase your commitment to giving, further Effective giving is important because top Farmed Animal Funders release briefings and research connect you with a giving community, and inspire others. giving options are plausibly many times more different promising areas. -

The Definition of Effective Altruism

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 19/08/19, SPi 1 The Definition of Effective Altruism William MacAskill There are many problems in the world today. Over 750 million people live on less than $1.90 per day (at purchasing power parity).1 Around 6 million children die each year of easily preventable causes such as malaria, diarrhea, or pneumonia.2 Climate change is set to wreak environmental havoc and cost the economy tril- lions of dollars.3 A third of women worldwide have suffered from sexual or other physical violence in their lives.4 More than 3,000 nuclear warheads are in high-alert ready-to-launch status around the globe.5 Bacteria are becoming antibiotic- resistant.6 Partisanship is increasing, and democracy may be in decline.7 Given that the world has so many problems, and that these problems are so severe, surely we have a responsibility to do something about them. But what? There are countless problems that we could be addressing, and many different ways of addressing each of those problems. Moreover, our resources are scarce, so as individuals and even as a globe we can’t solve all these problems at once. So we must make decisions about how to allocate the resources we have. But on what basis should we make such decisions? The effective altruism movement has pioneered one approach. Those in this movement try to figure out, of all the different uses of our resources, which uses will do the most good, impartially considered. This movement is gathering con- siderable steam. There are now thousands of people around the world who have chosen -

AIDA Hearing on AI and Competitiveness of 23 March 2021

SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN A DIGITAL AGE (AIDA) HEARING ON AI AND COMPETITIVENESS Panel I: AI Governance Kristi Talving, Deputy Secretary General for Business Environment, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications, Estonia Khalil Rouhana, Deputy Director General DG-CONNECT (CNECT), European Commission Kay Firth-Butterfield, Head of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learnings; Member of the Executive Committee, World Economic Forum Dr. Sebastian Wieczorek, Vice President – Artificial Intelligence Technology, SAP SE, external expert (until October 2020) in the study commission on AI in the Bundestag * * * Panel II: the perspective of Business and the Industry Prof. Volker Markl, Chair of Research Group at TU Berlin, Database Systems and Information Management, Director of the Intelligent Analytics for Massive Data Research Group at DFKI and Director of the Berlin Big Data Center and Secretary of the VLDB Endowment Moojan Asghari, Cofounder/Initiator of Women in AI, Founder/CEO of Thousand Eyes On Me Marina Geymonat, Expert for AI strategy @ Ministry for Economic Development, Italy. Head, Artificial intelligence Platform @TIM, Telecom Italia Group Jaan Tallinn, founding engineer of Skype and Kazaa as well as a cofounder of the Cambridge Centre for the Study of Existential Risk and Future of Life Institute 2 23-03-2021 BRUSSELS TUESDAY 23 MARCH 2021 1-002-0000 IN THE CHAIR: DRAGOŞ TUDORACHE Chair of the Special Committee on Artificial Intelligence in a Digital Age (The meeting opened at 9.06) Opening remarks 1-003-0000 Chair. – Good morning dear colleagues. I hope you are all connected and you can hear and see us in the room. Welcome to this new hearing of our committee. -

Ssoar-2020-Selle-Der Effektive Altruismus Als Neue.Pdf

www.ssoar.info Der effektive Altruismus als neue Größe auf dem deutschen Spendenmarkt: Analyse von Spendermotivation und Leistungsmerkmalen von Nichtregierungsorganisationen (NRO) auf das Spenderverhalten; eine Handlungsempfehlung für klassische NRO Selle, Julia Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Arbeitspapier / working paper Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Selle, J. (2020). Der effektive Altruismus als neue Größe auf dem deutschen Spendenmarkt: Analyse von Spendermotivation und Leistungsmerkmalen von Nichtregierungsorganisationen (NRO) auf das Spenderverhalten; eine Handlungsempfehlung für klassische NRO. (Opuscula, 137). Berlin: Maecenata Institut für Philanthropie und Zivilgesellschaft. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-67950-4 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.de MAECENATA Julia Selle Der effektive Altruismus als neue Größe auf dem deutschen Spendenmarkt Analyse von Spendermotivation und Leistungsmerkmalen von Nichtregierungsorganisationen (NRO) auf das Spenderverhalten. Eine Handlungsempfehlung für klassische NRO. Opusculum Nr.137 Juni 2020 Die Autorin Julia Selle studierte an den Universität