First Attempts at Imitating James Joyce's Ulysses in Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intermedialtranslation As Circulation

Journal of World Literature 5 (2020) 568–586 brill.com/jwl Intermedial Translation as Circulation Chu Tien-wen, Taiwan New Cinema, and Taiwan Literature Jessica Siu-yin Yeung soas University of London, London, UK [email protected] Abstract We generally believe that literature first circulates nationally and then scales up through translation and reception at an international level. In contrast, I argue that Taiwan literature first attained international acclaim through intermedial translation during the New Cinema period (1982–90) and was only then subsequently recognized nationally. These intermedial translations included not only adaptations of literature for film, but also collaborations between authors who acted as screenwriters and film- makers. The films resulting from these collaborations repositioned Taiwan as a mul- tilingual, multicultural and democratic nation. These shifts in media facilitated the circulation of these new narratives. Filmmakers could circumvent censorship at home and reach international audiences at Western film festivals. The international success ensured the wide circulation of these narratives in Taiwan. Keywords Taiwan – screenplay – film – allegory – cultural policy 1 Introduction We normally think of literature as circulating beyond the context in which it is written when it obtains national renown, which subsequently leads to interna- tional recognition through translation. In this article, I argue that the contem- porary Taiwanese writer, Chu Tien-wen (b. 1956)’s short stories and screenplays first attained international acclaim through the mode of intermedial transla- tion during the New Cinema period (1982–90) before they gained recognition © jessica siu-yin yeung, 2020 | doi:10.1163/24056480-00504005 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the cc by 4.0Downloaded license. -

Lady General Hua Mulan (1964)

Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2016, 4, 55-61 Published Online April 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2016.44008 Praises of Household Happiness in Social Turmoil: Lady General Hua Mulan (1964) Yuan Tian Department of General Education, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau, China Received 17 March 2016; accepted 16 April 2016; published 19 April 2016 Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract The relationship between film and culture can be seen from the adaptations that historical fiction films make on these original ancient stories or literary works under the influence of concurrent cultural contexts. In other words, these films are always used to reflect and react on the times in which they are made, instead of the past in which they are set. Therefore film makers add abun- dant up-to-date elements into traditional stories and constantly explore new ways of narration, an effort that turns their productions into live records of certain social and historical periods, com- bining macro and micro approaches to cultural backgrounds, both audible and visual. Pinning on this new angle of reviewing the old days, this paper aims to uncover the identity crisis of Hong Kong residents under the mutual influence of nostalgia and rebellious ideas in the 1960s recon- structed in the Huangmei Opera film Lady General Hua Mulan (1964) together with the analysis of the social historical reasons hidden behind. -

The Impacts of Modernity on Family Structure and Function : a Study Among Beijing, Hong Kong and Yunnan Families

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of Sociology and Social Policy 1-1-2012 The impacts of modernity on family structure and function : a study among Beijing, Hong Kong and Yunnan families Ting CAO Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/soc_etd Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons Recommended Citation Cao, T. (2012). The impacts of modernity on family structure and function: A study among Beijing, Hong Kong and Yunnan families (Doctoral dissertation, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.14793/soc_etd.29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology and Social Policy at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. THE IMPACTS OF MODERNITY ON FAMILY STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION: A STUDY AMONG BEIJING, HONG KONG AND YUNNAN FAMILIES CAO TING PHD LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2012 THE IMPACTS OF MODERNITY ON FAMILY STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION: A STUDY AMONG BEIJING, HONG KONG AND YUNNAN FAMILIES by CAO Ting A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Sciences (Sociology) LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2012 ABSTRACT The Impacts of Modernity on Family Structure and Function: a Study among Beijing, Hong Kong, and Yunnan Families by CAO Ting Doctor of Philosophy For a generation in many sociological literatures, China has provided the example of traditional family with good intra-familial relationship, filial piety and extended family support which is unusually stable and substantially unchanged. -

Writing Memory

Corso di Dottorato di ricerca in Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa, 30° ciclo ED 120 – Littérature française et comparée EA 172 Centre d'études et de recherches comparatistes WRITING MEMORY: GLOBAL CHINESE LITERATURE IN POLYGLOSSIA Thèse en cotutelle soutenue le 6 juillet 2018 à l’Université Ca’ Foscari Venezia en vue de l’obtention du grade académique de : Dottore di ricerca in Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa (Ca’ Foscari), SSD: L-OR/21 Docteur en Littérature générale et comparée (Paris 3) Directeurs de recherche Mme Nicoletta Pesaro (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) M. Yinde Zhang (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Membres du jury M. Philippe Daros (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Mme Barbara Leonesi (Università degli Studi di Torino) Mme Nicoletta Pesaro (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) M. Yinde Zhang (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Doctorante Martina Codeluppi Année académique 2017/18 Corso di Dottorato di ricerca in Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa, 30° ciclo ED 120 – Littérature française et comparée EA 172 Centre d'études et de recherches comparatistes Tesi in cotutela con l’Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3: WRITING MEMORY: GLOBAL CHINESE LITERATURE IN POLYGLOSSIA SSD: L-OR/21 – Littérature générale et comparée Coordinatore del Dottorato Prof. Patrick Heinrich (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) Supervisori Prof.ssa Nicoletta Pesaro (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) Prof. Yinde Zhang (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Dottoranda Martina Codeluppi Matricola 840376 3 Écrire la mémoire : littérature chinoise globale en polyglossie Résumé : Cette thèse vise à examiner la représentation des mémoires fictionnelles dans le cadre global de la littérature chinoise contemporaine, en montrant l’influence du déplacement et du translinguisme sur les œuvres des auteurs qui écrivent soit de la Chine continentale soit d’outre-mer, et qui s’expriment à travers des langues différentes. -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966 Xianmin Shen University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2015 Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966 Xianmin Shen University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Shen, X.(2015). Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3190 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DESTINATION HONG KONG: NEGOTIATING LOCALITY IN HONG KONG NOVELS 1945-1966 by Xianmin Shen Bachelor of Arts Tsinghua University, 2007 Master of Philosophy of Arts Hong Kong Baptist University, 2010 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Jie Guo, Major Professor Michael Gibbs Hill, Committee Member Krista Van Fleit Hang, Committee Member Katherine Adams, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Xianmin Shen, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Several institutes and individuals have provided financial, physical, and academic supports that contributed to the completion of this dissertation. First the Department of Literatures, Languages, and Cultures at the University of South Carolina have supported this study by providing graduate assistantship. The Carroll T. and Edward B. Cantey, Jr. Bicentennial Fellowship in Liberal Arts and the Ceny Fellowship have also provided financial support for my research in Hong Kong in July 2013. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details In the Mood for Travel: Mobility, Gender and Nostalgia in Wong Kar-wai’s Cinematic Hong Kong Lei, Chin Pang Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex August 2012 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature___________________________ Acknowledgement “Making films is just like holding water with your hands. No matter how hard you try, you will still lose much of it.” Chinese director Zhang Yimou expresses the difficulty of film making this way. For him, a perfect film is non-existent. At the end of my doctoral study, Zhang’s words ran through my mind. In the past several years, I worked hard to hold the water in my hands – to make this thesis as good as possible. No matter how much water I have finally managed to hold, this difficult task, however, cannot be carried out without the support given by the following people. -

Betty Oi-Kei Pun

Intersemiosis in Film: A Metafunctional and Multimodal Exploration of Colour and Sound in the Films of Wong Kar-wai Betty Oi-Kei Pun A thesis submitted to the University of New South Wales In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Chinese Studies and Department of Linguistics School of Modern Language Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales Australia 2005 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed ……………………………………………………………… i Abstract Intersemiosis in Film: A Metafunctional and Multimodal Exploration of Colour and Sound in the Films of Wong Kar-wai This study explores two stylistic features in the films of contemporary Hong Kong film-maker Wong Kar-wai: colour and sound. In particular, it focuses on how transitions in colour palettes (e.g. from a natural colour spectrum to a monochromatic effect of black-and-white) and specific sound resources (such as silence) function as important semiotic resources in the films, even when they appear to create a disjunctive effect. -

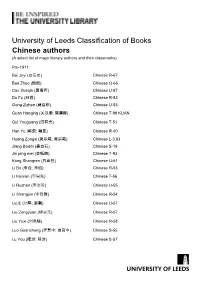

University of Leeds Classification of Books Chinese Authors (A Select List of Major Literary Authors and Their Classmarks)

University of Leeds Classification of Books Chinese authors (A select list of major literary authors and their classmarks) Pre-1911: Bai Juyi (白居易) Chinese R-67 Bao Zhao (鮑照) Chinese Q-66 Cao Xueqin (曹雪芹) Chinese U-87 Du Fu (杜甫) Chinese R-83 Gong Zizhen (龔自珍) Chinese U-53 Guan Hanqing (关汉卿; 關漢卿) Chinese T-99 KUAN Gui Youguang (归有光) Chinese T-51 Han Yu (韩愈; 韓愈) Chinese R-40 Huang Zongxi (黄宗羲; 黃宗羲) Chinese L-3.83 Jiang Baishi (姜白石) Chinese S-19 Jin ping mei (金瓶梅) Chinese T-93 Kong Shangren (孔尚任) Chinese U-51 Li Bo (李白; 李伯) Chinese R-53 Li Kaixian (李開先) Chinese T-56 Li Ruzhen (李汝珍) Chinese U-55 Li Shangyin (李商隱) Chinese R-54 Liu E (刘鹗; 劉鶚) Chinese U-57 Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元) Chinese R-57 Liu Yuxi (刘禹锡) Chinese R-58 Luo Guanzhong (罗贯中; 羅貫中) Chinese S-55 Lu You (陆游; 陸游) Chinese S-57 Ma Zhiyuan (马致远; 馬致遠) Chinese T-59 Meng Haoran (孟浩然) Chinese R-60 Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修; 歐陽修) Chinese S-64 Pu Songling (蒲松龄; 蒲松齡) Chinese U-70 Qu Yuan (屈原) Chinese Q-20 Ruan Ji (阮籍) Chinese Q-50 Shui hu zhuan (水浒传; 水滸傳) Chinese T-75 Su Manshu (苏曼殊; 蘇曼殊) Chinese U-99 SU Su Shi (苏轼; 蘇軾) Chinese S-78 Tang Xianzu (汤显祖; 湯顯祖) Chinese T-80 Tao Qian (陶潛) Chinese Q-81 Wang Anshi (王安石) Chinese S-89 Wang Shifu (王實甫) Chinese S-90 Wang Shizhen (王世貞) Chinese T-92 Wu Cheng’en (吳承恩) Chinese T-99 WU Wu Jingzi (吴敬梓; 吳敬梓) Chinese U-91 Wang Wei (王维; 王維) Chinese R-90 Ye Shi (叶适; 葉適) Chinese S-96 Yu Xin (庾信) Chinese Q-97 Yuan Mei (袁枚) Chinese U-96 Yuan Zhen (元稹) Chinese R-96 Zhang Juzheng (張居正) Chinese T-19 After 1911: [The catalogue should be used to verify classmarks in view of the on-going -

A Study of Xu Xu's Ghost Love and Its Three Film Adaptations THESIS

Allegories and Appropriations of the ―Ghost‖: A Study of Xu Xu‘s Ghost Love and Its Three Film Adaptations THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Qin Chen Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Master's Examination Committee: Kirk Denton, Advisor Patricia Sieber Copyright by Qin Chen 2010 Abstract This thesis is a comparative study of Xu Xu‘s (1908-1980) novella Ghost Love (1937) and three film adaptations made in 1941, 1956 and 1995. As one of the most popular writers during the Republican period, Xu Xu is famous for fiction characterized by a cosmopolitan atmosphere, exoticism, and recounting fantastic encounters. Ghost Love, his first well-known work, presents the traditional narrative of ―a man encountering a female ghost,‖ but also embodies serious psychological, philosophical, and even political meanings. The approach applied to this thesis is semiotic and focuses on how each text reflects the particular reality and ethos of its time. In other words, in analyzing how Xu‘s original text and the three film adaptations present the same ―ghost story,‖ as well as different allegories hidden behind their appropriations of the image of the ―ghost,‖ the thesis seeks to broaden our understanding of the history, society, and culture of some eventful periods in twentieth-century China—prewar Shanghai (Chapter 1), wartime Shanghai (Chapter 2), post-war Hong Kong (Chapter 3) and post-Mao mainland (Chapter 4). ii Dedication To my parents and my husband, Zhang Boying iii Acknowledgments This thesis owes a good deal to the DEALL teachers and mentors who have taught and helped me during the past two years at The Ohio State University, particularly my advisor, Dr. -

Utopia and Utopianism in the Contemporary Chinese Context

Utopia and Utopianism in the Contemporary Chinese Context Texts, Ideas, Spaces Edited by David Der-wei Wang, Angela Ki Che Leung, and Zhang Yinde This publication has been generously supported by the Hong Kong Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences. Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong https://hkupress.hku.hk © 2020 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8528-36-3 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any informa- tion storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Preface vii David Der-wei Wang Prologue 1 The Formation and Evolution of the Concept of State in Chinese Culture Cho-yun Hsu (許倬雲) (University of Pittsburgh) Part I. Discourses 1. Imagining “All under Heaven”: The Political, Intellectual, and Academic Background of a New Utopia 15 Ge Zhaoguang (葛兆光) (Fudan University, Shanghai) (Translated by Michael Duke and Josephine Chiu-Duke) 2. Liberalism and Utopianism in the New Culture Movement: Case Studies of Chen Duxiu and Hu Shi 36 Peter Zarrow (沙培德) (University of Connecticut, USA) 3. The Panglossian Dream and Dark Consciouscness: Modern Chinese Literature and Utopia 53 David Der-wei Wang (王德威) (Harvard University, USA) Part II. -

The Cantonese "Youth Film” and Music of the 1960S in Hong Kong CHAN, Pui Shan a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment O

The Cantonese "Youth Film” and Music of the 1960s in Hong Kong CHAN, Pui Shan A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Music The Chinese University of Hong Kong January 2011 |f 23APR2fi>J !?I Thesis Committee Professor YU Siu Wah (Chair) Professor Michael Edward McCLELLAN (Thesis Supervisor) Professor Victor Amaro VICENTE (Committee Member) Professor LI Siu Leung (External Examiner) X i Contents Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Chapter 1: 1 The Political and Social Influence on the Development of Hong Kong Film Industry and the Cantonese Cinema in the 1950s and the 1960s Chapter 2: 24 Defining the Genre: Three Characteristics of Hong Kong Cantonese Youth Film Chapter 3: 53 The Functions and Characteristics of Song in Cantonese Youth Film Chapter 4: 87 The Modernity of Cantonese Cinema and the City (Hong Kong) Conclusion: 104 Hong Kong Cantonese Youth Film and the Construction of Identity • Appendix 1 107 Appendix 2 109 Appendix 3 \\\ Bibliography 112 • ii Acknowledgements I am grateful for the teaching offered by the teaching staff and the sharing among friends at the Music Department of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. This experience is valuable to me. I have to thank Ada Chan, Lucy Choi, Angel Tsui, Julia Heung and Carman Tsang for their encouragement and prayers. I would also like to express my gratitude to my family which allowed me to pursue my studies in Music and Ethnomusicology. Furthermore, I cannot give enough thanks to my supervisor, Professor Michael E. McClellan for his patience, understanding, kindness, guidance, thoughtful and substantial support.