Cvckc-2017-0293-0311

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edible Insects

1.04cm spine for 208pg on 90g eco paper ISSN 0258-6150 FAO 171 FORESTRY 171 PAPER FAO FORESTRY PAPER 171 Edible insects Edible insects Future prospects for food and feed security Future prospects for food and feed security Edible insects have always been a part of human diets, but in some societies there remains a degree of disdain Edible insects: future prospects for food and feed security and disgust for their consumption. Although the majority of consumed insects are gathered in forest habitats, mass-rearing systems are being developed in many countries. Insects offer a significant opportunity to merge traditional knowledge and modern science to improve human food security worldwide. This publication describes the contribution of insects to food security and examines future prospects for raising insects at a commercial scale to improve food and feed production, diversify diets, and support livelihoods in both developing and developed countries. It shows the many traditional and potential new uses of insects for direct human consumption and the opportunities for and constraints to farming them for food and feed. It examines the body of research on issues such as insect nutrition and food safety, the use of insects as animal feed, and the processing and preservation of insects and their products. It highlights the need to develop a regulatory framework to govern the use of insects for food security. And it presents case studies and examples from around the world. Edible insects are a promising alternative to the conventional production of meat, either for direct human consumption or for indirect use as feedstock. -

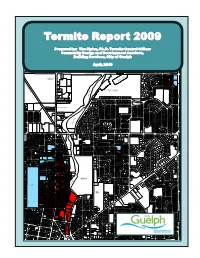

Observed Termite Activity in Sector 2 in 2009

Termite Report 2009 Prepared by: Tim Myles, Ph.D. Termite Control Officer Community Design and Development Services, Building Services, City of Guelph COUNTRY CLUB GOLFVIEW R D . GLEN BR OOK D R . ISLIN GTON April, 2010 AVE. FER N D ALE WOOLWICH ST. D ALEBR OOK PL. SPEED RIVER W OOD LAW N R D . W GOLFVIEWRD. W OOD LAW N R D . E W OOD LAW N D EVONSHIRE W IN D SOR ST. CT. C EMETER Y GUELPH JUNCTION RAILWAY FAIRWAY LANE WINDERMERE INVERNESS DR. INVERNESS KINGS ETON PL.ETON BALMOR AL D R . LEY ST. COUNTRY CLUB GOLF C OU R SE C T. BERKLEY PL. WINDSOR SPEED RIVER RIVERVIEW PLACE BALMORALDR. WOOLWICH ST. WOOLWICH W AVER LEY D R . MARILYN DR. KEN SIN GTON ST. D ELTA ST. R IVER SID E PAR K WOLSELEY RD. LAN GSIDST. E VERMONT ST. BAILEY AVE. DAKOTA DR. DAKOTA KENSINGTON ST. KENSINGTON RD N ST. STEVENSON COLLINGWOODST. KENSINGTON ST. KENSINGTON METCALFEST. CLIVE AVE. CLIVE DELHI ST. C ATH C AR T ST. SEN IOR BEATTIE ST BEATTIE LILAC PL. C EN TR E SPEED RIVER SH AFTESBU R Y AVE. KATHLEEN ST. KATHLEEN BAILEY AVE. BAILEY FREEMAN AVE. FREEMAN WAVERLY DR. WAVERLY DUMBARTON ST. DUMBARTON VICTORIA RD. N RD. VICTORIA KNIGHTSWOOD BLVD. KNIGHTSWOOD SHERIDAN ST. SHERIDAN FR EEMAN AVE. RIVERVIEW DR. ST. DUMBARTON RIVERSIDE PARK SU MAC PL. BRIGHTON ST. BRIGHTON KITCHENER AVE. ST. RENFIELD GEMMEL NELSON RD. LN. AVE. GLAD STON E AVE. MARLBOROUGH GLADSTONE SPEEDVALE AVE. E ACORN PL. CHESTER ST. CT SHERWOOD DR. ALEXANDRA KNIGHTSWOOD MANHATTAN BLVD. -

This Is Only a Guide of Animals That MAY Be Legal in a State. Due to The

OREGON LEGAL PET GUIDE POSSESS IMPORT TAKE COMMENTS This is only a guide of animals that MAY be legal in a state. Due to the extensive amount of laws involved that are constantly changing, UAPPEAL cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information. Users are responsible for checking all laws BEFORE getting an animal. Legal as Pets as Legal ODFWPermit Pets for Legal ODFWPermit Permit Ag Pets for Legal ARACHNID, CENTIPEDE, MILLIPEDE Fungus Gnat Killer (various) No No No Approved Invertebrate List - Not approved for pets/pet food Millipede, Desert Yes No Yes No No NA Approved Invertebrate - legal pets; Import - See Ag Millipede, Giant African (Thyropygus ) Yes No Yes No No NA Approved Invertebrate - legal pets; Import - See Ag Millipede, Giant African Black Yes No Yes No No NA Approved Invertebrate - legal pets; Import - See Ag Millipede, Round-backed (Spirobolus ) No No No Approved Invertebrate List - Not approved for pets/pet food Mite, Bindweed Gall No No No Approved Invertebrate List - Not approved for pets/pet food Mite, Cyclamen No No No Approved Invertebrate List - Not approved for pets/pet food Mite, Dried Fruit No No No Approved Invertebrate List - Not approved for pets/pet food Mite, Dust No No No Approved Invertebrate List - Not approved for pets/pet food Mite, Flour No No No Approved Invertebrate List - Not approved for pets/pet food Mite, Gorse Spider No No No Approved Invertebrate List - Not approved for pets/pet food Mite, Mold No No No Approved Invertebrate List - Not approved for pets/pet food Mite, Predator (various) No No -

The Alpha-Linolenic Acid Requirements of Developing Heliothines

The alpha-linolenic acid requirements of developing Heliothines Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) Vorgelegt dem Rat der Biologisch-Pharmazeutischen Fakult¨at der Friedrich-Schiller-Universit¨atJena von Brent Sørensen (M. Sc.) geboren am 30. Dezember 1979 in Edmonton, Kanada Demo Watermark Version, http://www.verydoc.com and http://www.verypdf.com Gutachter: 1. Prof. Dr. David G. Heckel, Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecol- ogy, Jena, Germany 2. Prof. Dr. Klaus H. Hoffmann, Universit¨atBayreuth, Bayreuth, Ger- many 3. Prof. Dr. Spencer T. Behmer, Texas A & M University, College Sta- tion, Texas, USA Tag des ¨offentlichen Verteidigung: 23. Oktober 2012 1 Demo Watermark Version, http://www.verydoc.com and http://www.verypdf.com Contents List of figures vi List of tables vii Acknowledgements viii Abstract x Zusammenfassung xii 1 A review of fatty acid metabolism and function in Lepi- doptera and current and future applications 1 1.1 Introduction . .1 1.2 Fatty acid structure and nomenclature . .3 1.2.1 Fatty acids . .3 1.2.2 Esterified fatty acids . .5 1.3 Lipid metabolism in Lepidoptera . .5 1.3.1 Metabolism of dietary fatty acids . .6 1.3.2 Lipogenesis . .7 1.4 Function of fatty acids in insects . .9 1.4.1 Protection . .9 1.4.2 Phagostimulator . 10 1.4.3 Energy stores . 10 1.4.4 Oviposition deterrent . 11 i Demo Watermark Version, http://www.verydoc.com and http://www.verypdf.com 1.5 Fatty acid metabolites in Lepidoptera . 11 1.5.1 Linoleic acid metabolites . 12 1.5.2 Linolenic acid metabolites . -

Tenebrio Molitor L., Entomophagy and Processing Into Ready to Use Therapeutic Ingredients: a Review

Journal of Nutritional Health & Food Engineering Review Article Open Access Tenebrio molitor L., entomophagy and processing into ready to use therapeutic ingredients: a review Abstract Volume 8 Issue 3 - 2018 The consumption of insects is known as entomophagy. Edible insects have been Sofia Feng consumed for a long time in the traditional diets of many non-Western countries, but Department of Food, Bioprocessing and Nutritional Sciences, in recent times, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) NC State University, USA recognize them as having a high potential to treat malnutrition and food shortages without requiring large amounts of land or infrastructure. The larvae of Tenebrio Correspondence: Sofia Feng, Department of Food, Molitor L., the mealworm, have been processed to be as high in protein content as Bioprocessing and Nutritional Sciences, NC State University, fish and meat. They are also fairly high in fatty acids, especially polyunsaturated 400 Dan Allen Dr. Raleigh, NC, 27695, USA, Tel +1 (919)-454- omega-3 and 6, comparable with the content of fish and higher than in beef and pork. 1494, Email [email protected] They possess a variety of vitamins and minerals such as: magnesium, copper, iron, manganese, phosphorus, selenium and zinc as well as, riboflavin, pantothenic acid Received: June 14, 2018 | Published: June 22, 2018 and biotin. These qualities would make them a possible food ingredient in the US (based on current novelty trends) if US consumers would acknowledge and learn to accept insect-based products. In areas where insects are a traditional part of the diet, processed mealworms can be used as a successful ingredient in emergency relief meals. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0261934 A1 FISCHER Et Al

US 2010O261934A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0261934 A1 FISCHER et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 14, 2010 (54) METHOD FOR PREPARING (30) Foreign Application Priority Data 2,6-DIETHYL-4-METHYLPHENYLACETIC ACD Nov. 4, 2004 (DE) ......................... 1020040531919 (75) Inventors: Reiner FISCHER, Monheim (DE); Publication Classification SEWA his (DE): (51) Int. Cl. ark winem Urewes, C07C 5 L/09 (2006.01) Langenfeld (DE); Dieter Feucht, C07C 5 L/08 (2006.01) Eschborn (DE): Olga Malsam, Rosrath (DE); Guido Bojack, (52) U.S. Cl. ........................................................ 562/496 Wiesbaden (DE); Christian Arnold, Langenfeld (DE). Thomas (57) ABSTRACT Auler, Leichlingen (DE); Jeffrey Marin Hills, Idstein (DE); Heinz The invention relates to novel 2,6-diethyl-4-methylphenyl Kehne, Hofheim (DE); Chris substituted tetramic acid derivatives of the formula (I) Rosinger, Hofheim (DE) Correspondence Address: G (I) STERNE, KESSLER, GOLDSTEIN & FOX P.L. V L.C. A O CHs 1100 NEW YORKAVENUE, N.W. B WASHINGTON, DC 20005 (US) \ -N CH3 (73) Assignee: Bayer CropScience AG, Monheim (DE) O C2H5 (21) Appl. No.: 12/821,831 in which A, B, D and Gare as defined above, to a plurality of (22) Filed: Jun. 23, 2010 processes and intermediates for their preparation and to their O O use as pesticides and/or herbicides, and also to selectively Related U.S. Application Data herbicidal compositions comprising, firstly, the 2,6-diethyl (62) Division of application No. 1 1/666,870, filed on Mar. 4-methylphenyl-substituted tetramic acid derivatives of the 24, 2008, filed as application No. PCT/EP2005/ formula (I) and, secondly, at least one crop plant tolerance 011343 on Oct. -

Ppm------IU/Kg of Choline and B-Vitamins

CPro CFat ASH ADF Ca:P Na Cu Fe Zn Mn Se Mo Item DM[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] Ca[6] P[7] ratio[8] Mg[9] [10] K[11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] A[18] E[19] REF Item Genus Species Type Comments All insects provide high amounts ------------------%------------------ ----------------------%---------------------- ----------------ppm------------------ IU/kg of choline and B-vitamins. Blattodea All roaches are lacking linoleic (Roaches) acid and linolenic acid. Cockroach, Cockroach, American 38.7 53.9 28.4 3.3 9.4 0.2 0.5 1:2.5 0.08 0.27 0.87 14 90 57 5 0.36 1 American Periplaneta americana I Rusty Red Rusty Red (small) 20.82 76.05 14.45 7.88 10.87 0.24 1.22 1:5 0.21 0.53 1.6 39 102 214 25 N/A 0.6 120 21.7 10 (small) Blatta lateralis I Rusty Red Rusty Red (medium) 28.27 62.85 26.5 6.89 12.75 0.19 0.95 1:5 0.15 0.37 1.18 33.5 89.5 164.5 18 N/A 0.6 83 17 10 (medium) Blatta lateralis I Hissing Hissing Cockroach Cockroach High in Iron, good source Vits A & (small) 30.83 63.35 20.3 8.49 13.12 0.25 0.93 1:4 0.24 0.33 1.24 22.5 153.5 202 10 N/A 0.3 182 23.9 10 (small) Gromphadorhinaportentosa I E Hissing Hissing Cockroach Cockroach High in Iron, good source Vits A & (large) 38.95 62.52 24.56 4.06 10.22 0.17 0.57 1:3.5 0.17 0.21 0.87 18.8 216 168.2 6.4 N/A 0.4 386 21.1 10 (large) Gromphadorhinaportentosa I E Six-spotted Six-spotted cockroach cockroach (small) 42.78 52.1 43.1 2.98 N/A 0.08 0.46 1:6 0.08 0.4 0.75 12 55 124 5 N/A 0.4 192 18.4 10 (small) Eublaberus distanti I Not the best roach feeder choice. -

1. Padil Species Factsheet Scientific Name: Common Name Image

1. PaDIL Species Factsheet Scientific Name: Chilecomadia valdiviana (Philippi) (Lepidoptera: Cossidae) Common Name Carpenter worm Live link: http://www.padil.gov.au/pests-and-diseases/Pest/Main/136297 Image Library Australian Biosecurity Live link: http://www.padil.gov.au/pests-and-diseases/ Partners for Australian Biosecurity image library Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment https://www.awe.gov.au/ Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Western Australia https://dpird.wa.gov.au/ Plant Health Australia https://www.planthealthaustralia.com.au/ Museums Victoria https://museumsvictoria.com.au/ 2. Species Information 2.1. Details Specimen Contact: Museum Victoria - [email protected] Author: Walker, K. Citation: Walker, K. (2006) Carpenter worm(Chilecomadia valdiviana)Updated on 10/21/2011 Available online: PaDIL - http://www.padil.gov.au Image Use: Free for use under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY- NC 4.0) 2.2. URL Live link: http://www.padil.gov.au/pests-and-diseases/Pest/Main/136297 2.3. Facets Status: Exotic species - absent from Australia Group: Moths Commodity Overview: Horticulture, Forestry Commodity Type: Timber, Fresh Stems Distribution: Central and South America 2.4. Other Names Chilean carpenter worm PESTF - 2.5. Diagnostic Notes There are several species of the cossid moth genus _Chilecomadia_ in South America: - _Chilecomadia discoclathratus_ Bryk 1945 - _Chilecomadia moorei_ Silva Figuero 1915 - _Chilecomadia munroei_ (Clench, 1957) - _Chilecomadia valdiviana_ Philippi 1860 - _Chilecomadia zeuzerina_ Bryk 1945 The larvae of _Chilecomadia moorei_, called the Chilean Moth or Butterworm of Trevo worm, is commercially collected and sold in the pet food trade. The carpentar worm, _Chilecomadia valdiviana_, is pest species. -

Oregon's Rules and Regulations Summary

OR - 1 of 32 OREGON SUMMARIES OF EXTERIOR QUARANTINES 09/22/2020 State of Oregon Department of Agriculture, Plant Program 635 Capitol Street NE Salem, Oregon 97301-2532 Telephone: 503/986-4644 FAX: 503/986-4786 General contact e-mail: [email protected] Helmuth Rogg Director, Plant Protection & Conservation Programs Area Open Nursery & Christmas Tree Program Manager Tim Butler Hemp/Weeds Program Manager Jake Bodart Insect Pest Prevention & Management Program Manager The information, as provided, is for informational purposes only and should not be interpreted as complete, nor should it be considered legally binding. Coordination with both your state and the destination state plant regulatory agency listed above may be necessary to stay up-to-date on revised requirements. DEFINITIONS “Nursery Stock” includes all botanically classified plants or any part thereof, such as floral stock, herbaceous plants, bulbs, corms, roots, scions, grafts, cuttings, fruit pits, seeds of fruits, forest and ornamental trees and shrubs, berry plants, and all trees, shrubs and vines and plants collected in the wild that are grown or kept for propagation or sale. Nursery stock does not include: • Field and forage crops; • The seeds of grasses, cereal grains, vegetable crops and flowers; • The bulbs and tubers of vegetable crops; • Any vegetable or fruit used for food or feed; • Cut flowers, unless stems or other portions thereof are intended for propagation. GENERAL SHIPPING REQUIREMENTS a. Oregon grown nursery stock must be free of pests, diseases and noxious weeds and be accompanied by a shipping certificate issued by the Oregon Department of Agriculture. b. All nursery stock originating from other states must be accompanied by a shipping certificate issued by the plant regulatory agency of the state of origin. -

Insects As Food and Feed: Nutrient Composition and Environmental Impact

Insects as food and feed: Nutrient composition and environmental impact Dennis G.A.B. Oonincx Thesis committee Promotors Prof. Dr A. van Huis Personal chair at the Laboratory of Entomology Wageningen University Prof. Dr J.J.A. van Loon Personal chair at the Laboratory of Entomology Wageningen University Other members Prof. Dr W.H. Hendriks, Wageningen University Dr T.V. Vellinga, Livestock Research, Wageningen University and Research Centre Dr B. Rumpold, Leibniz Institute for Agricultural Engineering, Potsdam-Bornim, Germany Dr P.G. Jones, Waltham Center for Pet Nutriton, Mars Petcare, Leicestershire, UK This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School of Production Ecology & Resource Conservation Insects as food and feed: Nutrient composition and environmental impact Dennis G.A.B. Oonincx Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Tuesday 6 January 2015 at 4 p.m. in the Aula. Dennis G.A.B. Oonincx Insects as food and feed: Nutrient composition and environmental impact, 208 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2015) With references, with summaries in Dutch and English ISBN 978-94-6257-178-5 Abstract Because of an increasing world population, with more demanding consumers, the demand for animal based protein is on the increase. To meet this increased demand, alternative sources of animal based protein are required. When compared to conventional production animals, insects are suggested to be an interesting protein source because they have a high reproductive capacity, high nutritional quality, and high feed conversion efficiency, they can use waste as feed and are suggested to be produced more sustainably. -

Nutrition of the Titicaca Water Frog (Telmatobius Culeus)

GHENT UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF VETERINARY MEDICINE Academic year 2016 - 2017 NUTRITION OF THE TITICACA WATER FROG (TELMATOBIUS CULEUS) by Stéphane KNOLL Promoters: Muñoz-Saravia Arturo Research Report as part of the Prof. dr. Janssens Geert P. J. Master's Dissertation © 2017 Stéphane KNOLL Disclaimer Universiteit Gent, its employees and/or students, give no warranty that the information provided in this thesis is accurate or exhaustive, nor that the content of this thesis will not constitute or result in any infringement of third-party rights. Universiteit Gent, its employees and/or students do not accept any liability or responsibility for any use which may be made of the content or information given in the thesis, nor for any reliance which may be placed on any advice or information provided in this thesis. GHENT UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF VETERINARY MEDICINE Academic year 2016 - 2017 NUTRITION OF THE TITICACA WATER FROG (TELMATOBIUS CULEUS) by Stéphane KNOLL Promoters: Muñoz-Saravia Arturo Research Report as part of the Prof. dr. Janssens Geert P. J. Master's Dissertation © 2017 Stéphane KNOLL Foreword: This research has been conducted as a part of the master’s degree at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of the Ghent University, Belgium. As third master student, graduating in the field of research, conducting a research project is an important part of the master dissertation. I feel very lucky for being assigned such an interesting topic and had the chance to travel abroad. For this reason, I would like to thank the Ghent University for the amazing opportunity to conduct research abroad and get some international experience. -

1. Padil Species Factsheet Scientific Name: Common Name Image

1. PaDIL Species Factsheet Scientific Name: Chilecomadia moorei Silva Figuero, 1915 (Lepidoptera: Cossidae: Cossinae) Common Name Butterworm Live link: http://www.padil.gov.au/pests-and-diseases/Pest/Main/141552 Image Library Australian Biosecurity Live link: http://www.padil.gov.au/pests-and-diseases/ Partners for Australian Biosecurity image library Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment https://www.awe.gov.au/ Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Western Australia https://dpird.wa.gov.au/ Plant Health Australia https://www.planthealthaustralia.com.au/ Museums Victoria https://museumsvictoria.com.au/ 2. Species Information 2.1. Details Specimen Contact: Museum Victoria - [email protected] Author: Clare McLellan Citation: Clare McLellan (2011) Butterworm(Chilecomadia moorei)Updated on 9/5/2011 Available online: PaDIL - http://www.padil.gov.au Image Use: Free for use under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY- NC 4.0) 2.2. URL Live link: http://www.padil.gov.au/pests-and-diseases/Pest/Main/141552 2.3. Facets Commodity Overview: Forestry Commodity Type: Fresh Stems, Timber Distribution: Central and South America Group: Moths Status: Uncertain Status - In Australia 2.4. Other Names Chilean Cossid moth Trevo worm 2.5. Diagnostic Notes The Chilean Moth (_Chilecomadia moorei_) is a moth of the Cossidae family. The Butterworm is the larval form and is commonly used as fishing bait in South America. Trevo Worm (_Chilecomadia moorei_) is the larval stage of the Chilean Moth. The worm feeds exclusively off the Trevo Plant (_Trevoa trinervis_), also native to the Chilean central region. 3. Diagnostic Images Chile.