The Groko Effect: Does the Popularity of CDU/CSU and SPD Suffer from Grand Coalitions?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deckblatt Berichte PV Und GS 32. Parteitag 2019.Indd

32. Parteitag der CDU Deutschlands 22. bis 23. November 2019, Leipziger Messe Bericht des Generalsekretärs der CDU Deutschlands Paul Ziemiak MdB TAGESORDNUNGSPUNKT 9 Bericht des Generalsekretärs der CDU Deutschlands, zugleich Einführung in die Anträge des Bundesvorstandes Paul Ziemiak MdB Paul Ziemiak, Generalsekretär der CDU: Liebe Antje! Verehrtes Tagungspräsidium! Sehr geehrte Bundeskanzlerin, liebe Angela! Liebe Annegret! Meine sehr verehrten Damen und Herren! Liebe Freundinnen und Freunde! Ich will gerne in diesen Leitantrag einführen und das gleichzeitig mit meinem Bericht als Generalsekretär verbinden. In Anbetracht der Zeit will ich es konkret, aber auch entsprechend knapp machen. Es ist mir ein tiefes Bedürfnis, mit Folgendem anzufangen: Liebe Annegret, das war eine starke Rede, die du hier heute gehalten hast. Du hast dieser Partei Richtung und Führung gegeben. Es hat Spaß und Freude gemacht, dir zuzuhören. (Beifall) Meine sehr verehrten Damen und Herren, liebe Freundinnen und Freunde, uns ist das C entwendet worden aus dem Konrad-Adenauer-Haus. Die ersten Reaktionen waren: Na ja, das passiert der CDU. – Ich finde, unsere Reaktionen haben dazu geführt, dass im Netz, gerade in sozialen Netzwerken, über christliche Werte und was sie bedeuten gesprochen wird. Ich bin Greenpeace zutiefst dankbar, dass sie mit ihrer Aktion gezeigt haben, wie wichtig es ist, dass wir eine christliche, soziale Partei in Deutschland haben, die sich an diesen Werten orientiert. (Beifall) Zu einer christlich demokratischen Partei gehört auch Demut. Deshalb will ich zu Anfang sagen, dass dieses Jahr ein herausforderndes Jahr, ein schwieriges Jahr war. Ja, wir haben auch Fehler gemacht, nicht in den letzten Tagen und Wochen, aber in den letzten Monaten, in denen wir falsch oder gar nicht auf Dinge, auch im Netz, reagiert haben. -

Saurer Apfel

Deutschland Länder. Parteichef Oskar La- fontaine habe „ganz deutli- che Worte gesprochen“, rühmt Ringstorff, „wir ent- scheiden hier, wie die Re- gierung gebildet wird“. Was für die Mecklenburg- Vorpommerschen Sozialde- mokraten das Beste ist, da sind sich Spitzengenossen vor Ort einig – ein echtes Bündnis mit der PDS. Nur so seien die Postkommuni- sten zu disziplinieren. Das Wahlergebnis zwinge die SPD, sagt der Noch-Bundes- tagsabgeordnete Tilo Brau- ne aus Greifswald, „in den K. B. KARWASZ sauren Apfel der rot-roten Sozialdemokrat Ringstorff (r.), PDS-Landeschef Holter (hinten M.)*: „Größere Nähe“ Koalition zu beißen“. Und selbst Justizminister Rolf Eg- die sich erst einmal in der Opposition re- gert, Intimfeind der PDS, hat eingelenkt. MECKLENBURG-VORPOMMERN generiert. Eggert schwächte seine Drohung ab, er ste- Daß Ringstorff die Union überhaupt he für ein SPD-PDS-Kabinett nicht zur Ver- Saurer Apfel zum – unverbindlichen – Plausch lud, und fügung: „Das müßte ich mir überlegen.“ zwar noch vor der PDS, war ein geschick- Eine wichtige Rolle dürfte bei den Ver- Die SPD in Schwerin ter Zug: So erhöht er den Druck auf die handlungen der beiden Wahlsieger spie- Postkommunisten, die unbedingt mit an len, wen die PDS als ministrabel präsen- ist offiziell nach allen Seiten die Macht wollen, ihre Forderungen im tiert. Ihren Chef Holter, 45, etwa hält verhandlungsbereit. Doch vornhinein zu mäßigen. Dieselbe Strate- Ringstorff für einen „lupenreinen Sozial- die Signale stehen auf Rot-Rot. gie hat der clevere SPD-Mann schon vor demokraten“. Der frühere FDJler Andreas vier Jahren mit umgekehrten Vorzeichen Bluhm, 38, für das Amt des Kultusmini- as eierst du so rum“, raunzte der erfolgreich angewandt, um den Preis für sters im Gespräch, tritt heute so jovial auf Vorsitzende der Gewerkschaft eine Große Koalition hochzutreiben. -

Media Information

Media information April 27, 2020 Production at Volkswagen in Wolfsburg begins again today – First vehicle to be produced is a Golf – Production will start at 10 to 15 percent of capacity, increasing to around 40 percent the following week – 100-point plan provides maximum health protection for employees – Ralf Brandstätter, COO of the Volkswagen Passenger Cars brand: “Step-by-step resumption of production is an important signal for the workforce, dealerships, suppliers and the wider economy.” – Minister-President of Lower-Saxony, Stephan Weil, visited the first early shift at the plant: “Boost vehicle sales quickly.” – Chairman of the Works Council, Bernd Osterloh: “The health of our colleagues has absolute priority when production resumes.” Media contact Wolfsburg – The Volkswagen Passenger Cars brand resumed vehicle production at Volkswagen Communications its Wolfsburg plant today with the early shift beginning at 6:30 a.m. Initially, Golf Jörn Roggenbuck Spokesperson Production production will recommence on a one-shift basis — with reduced capacity and longer Tel. +49-173-37607-55 cycle times. Today, some 8,000 employees are returning to the production halls. [email protected] Production of the Volkswagen Tiguan and Touran models as well as the SEAT Tarraco Markus Schlesag begins on Wednesday. Multi-shift operation is to get underway again the following Spokesperson Human Resources week. At the same time, some 2,600 suppliers, the majority of them located in Tel: +49 5361 9-871 15 Germany, have resumed production for Volkswagen’s main plant. Measures to protect [email protected] the health of the workforce have been significantly expanded. -

Helke Rausch

THEODOR-HEUSS-KOLLOQUIUM 2017 Liberalismus und Nationalsozialismus – eine Beziehungsgeschichte Helke Rausch Liberalismus und Nationalsozialismus bei Ernst Jäckh – liberaler Phoenix, Grenzgänger und atlantischer „Zivil-Apostel“ Momentaufnahme einer inszenierten Beziehungsgeschichte: Jäckh und Hitler in Berlin, April 1933 In seiner Eigenschaft als langjähriger Leiter der Deutschen Hochschule für Politik in Berlin 1920 bis 1933 kam Ernst Jäckh 1933 zu seinem unmittelbarsten Direktkontakt mit dem neu- en Regime und seinem „Führer“. Jäckh stand unter akutem Handlungsdruck, sich gegenüber den neuen Machthabern zu positionieren. Während er in seinen Memoiren und andernorts ein hagiographisches Bild von seiner eigenen Überlegenheit und Widerständigkeit im Um- gang mit Hitler zeichnete, demzufolge er phoenixgleich als standhaft liberaler Regimegegner dem Diktator entgegentrat,1 konnte er trotz dieser auf den Erhalt der Hochschule zielenden Unterredung seine Institution nicht halten. Wie auch immer Jäckhs Beziehungsstrategie ge- genüber dem NS Anfang 1933 ausgesehen haben mag, sein Kalkül schlug gründlich fehl. Er musste das übergriffige Regime gewähren lassen. Die offizielle Gleichschaltung der Hoch- schule zog sich zwar noch bis 1937 hin, bevor das Institut als Reichsanstalt firmieren und schließlich 1940 den „Auslandswissenschaften“ als dezidierten NS-Politikwissenschaften zu- geordnet werden sollte. 2 Schon zuvor aber löste Jäckh den Verein Deutsche Hochschule für Politik e.V. Ende April 1933 auf.3 These und Argument Die Symptomatik des Direktkontakts zwischen dem Liberalen Jäckh und der NS-Führung be- steht nicht so sehr in einem vordergründigen Lackmustest für Jäckhs liberalen Widerstands- 1 Jäckh tischte nach verschiedenen Seiten hin eine ominöse Widerstandsgeschichte auf. Die Sebstheroisierung in seinen Memoiren kippt fast zur Farce, vgl. etwa Ernst Jäckh: Weltsaat. Erlebtes und Erstrebtes, Stuttgart 1960, S. -

Mautner, Karl.Toc.Pdf

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project KARL F. MAUTNER Interviewed by: Thomas J. Dunnigan Initial interview date: May 12, 1993 opyright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Austria Austrian Army 1 35-1 36 Emigrated to US 1 40 US Army, World War II Berlin 1 45-1 5, Divided Berlin Soviet Blockade and US Airlift .urrency Reform- Westmark Elections, 01 4,1 Federal Basic 2a3 and Berlin East vs. West Berlin Revolt in East Berlin With Brandt and Other Personalities Bureau of .ultural Affairs - State Department 1 5,-1 61 European E5change Program Officer Berlin Task Force 1 61-1 65 Berlin Wall 6ice President 7ohnson8s visit to Berlin 9hartoum, Sudan 1 63-1 65 .hief of political Section Sudan8s North-South Rivalry .oup d8etat Department of State, Detailed to NASA 1 65 Negotiating Facilities Abroad Retirement 1 General .omments of .areer INTERVIEW %: Karl, my first (uestion to you is, give me your background. I understand that you were born in Austria and that you were engaged in what I would call political work from your early days and that you were active in opposition to the Na,is. ould you tell us something about that- MAUTNER: Well, that is an oversimplification. I 3as born on the 1st of February 1 15 in 6ienna and 3orked there, 3ent to school there, 3as a very poor student, and joined the Austrian army in 1 35 for a year. In 1 36 I got a job as accountant in a printing firm. I certainly couldn8t call myself an active opposition participant after the Anschluss. -

![Daran Angehängt: [IG K-PL 124] Mit Allen Anlagen](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9067/daran-angeh%C3%A4ngt-ig-k-pl-124-mit-allen-anlagen-519067.webp)

Daran Angehängt: [IG K-PL 124] Mit Allen Anlagen

JUNGE UNION und JUSOS: Daran angehängt: [IG_K-PL_124] mit allen Anlagen Umsetzung in IG-weite Referenzen Anlage 3.a [IG_O-PP_013] Anlage 3.b [IG_O-PP_012] Anlage 49c [IG_O-MP_008] Anlage V50 [IG_O-MP_003] Anlage V51 [IG_O-MP_004] Anlage V52 [IG_O-MP_002] Anlage V55 [IG_O-MF_001] Anlage V56 [IG_O-MP_005] Anlage V57 [IG_O-MP_007] Daran angehängt: [IG_K-PL_125] mit allen Anlagen Information der JUNGEN UNION Cc: CDU Präsidium und Vorstand An: Mitglieder des Bundesvorstandes der Jungen Union Angehängt: Email an A. Markstrahler vom 24.01.2019 [IG_K-PP_008] Email an A. Markstrahler vom 22.01.2019 [IG_K-PP_008] Email an CDU Präsidium und Vorstand vom 16.01.2019 (s.o.) Cc: CDU Präsidium und Vorstand Der vollständige Cc-Verteiler wie gehabt: '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; '[email protected]'; -

BUNDESRAT Stenografischer Bericht 818

Plenarprotokoll 818 BUNDESRAT Stenografischer Bericht 818. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 21. Dezember 2005 Inhalt: Gedenkansprache des Präsidenten zum 6. Gesetz zur Abschaffung der Eigenheim- Völkermord an Sinti und Roma im National- zulage (Drucksache 857/05) ...... 404 B sozialismus .............. 395 A Walter Hirche (Niedersachsen) ... 404 B Amtliche Mitteilungen ......... 397 A Prof. Dr. Andreas Pinkwart (Nord- rhein-Westfalen) ....... 405 B Zur Tagesordnung ........... 397 C Peer Steinbrück, Bundesminister der Finanzen .......... 405 D 1. Erklärung der Bundeskanzlerin .... 397 C Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin 397 D Beschluss zu 4 bis 6: Zustimmung gemäß Art. 105 Abs. 3 GG. ........ 408 D Präsident Peter Harry Carstensen . 401 B 2. Wahl des Vorsitzenden des Wirtschafts- 7. Erstes Gesetz zur Änderung des Zoll- ausschusses – gemäß § 12 Abs. 3 GO BR – fahndungsdienstgesetzes (Drucksache (Drucksache 843/05) ........ 401 D 858/05 [neu]) ............ 408 D Beschluss: Staatsminister Erwin Huber Beschluss: Zustimmung gemäß Art. 84 (Bayern) wird gewählt ....... 401 D Abs. 1 GG ............ 409 A 3. Fünftes Gesetz zur Änderung des Dritten 8. Gesetz über den Ausgleich von Arbeit- Buches Sozialgesetzbuch und anderer geberaufwendungen und zur Änderung Gesetze (Drucksache 854/05) ..... 401 D weiterer Gesetze (Drucksache 859/05) . 409 A Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Reinhart (Baden- Württemberg) ........ 402 A Gerry Kley (Sachsen-Anhalt) ... 409 A Karl-Josef Laumann (Nordrhein- Beschluss: Zustimmung gemäß Art. 84 Westfalen) .......... 403 B Abs. 1 GG ............ 410 A Beschluss: Kein Antrag gemäß Art. 77 Abs. 2 GG . ........... 404 B 9. Fünftes Gesetz zur Änderung der Bun- desnotarordnung (Drucksache 860/05) . 411 C 4. Gesetz zum Einstieg in ein steuerliches Sofortprogramm (Drucksache 855/05) Beschluss: Zustimmung gemäß Art. 84 Abs. 1 GG ............427*B in Verbindung mit 10. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2c73n9k4 Author Boyle, Michael Shane Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence By Michael Shane Boyle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair Professor Anton Kaes Professor Shannon Steen Fall 2012 The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence © Michael Shane Boyle All Rights Reserved, 2012 Abstract The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance After the Age of Affluence by Michael Shane Boyle Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair While much humanities scholarship focuses on the consequence of late capitalism’s cultural logic for artistic production and cultural consumption, this dissertation asks us to consider how the restructuring of capital accumulation in the postwar period similarly shaped activist practices in West Germany. From within the fields of theater and performance studies, “The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence” approaches this question historically. It surveys the types of performance that decolonization and New Left movements in 1960s West Germany used to engage reconfigurations in the global labor process and the emergence of anti-imperialist struggles internationally, from documentary drama and happenings to direct action tactics like street blockades and building occupations. -

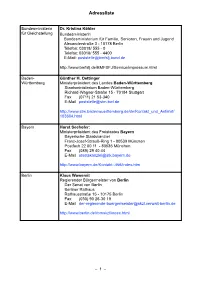

20091230 EU Direktive

Adressliste Bundesministerin Dr. Kristina Köhler für Gleichstellung Bundesministerin Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend Alexanderstraße 3 - 10178 Berlin Telefon: 03018/ 555 - 0 Telefax: 03018/ 555 - 4400 E-Mail: [email protected] http://www.bmfsfj.de/BMFSFJ/Service/impressum.html Baden- Günther H. Oettinger Württemberg Ministerpräsident des Landes Baden-Württemberg Staatsministerium Baden-Württemberg Richard-Wagner-Straße 15 - 70184 Stuttgart Fax (0711) 21 53-340 E-Mail [email protected] http://www.stm.badenwuerttemberg.de/de/Kontakt_und_Anfahrt/ 103604.html Bayern Horst Seehofer: Ministerpräsident des Freistaates Bayern Bayerische Staatskanzlei Franz-Josef-Strauß-Ring 1 - 80539 München Postfach 22 00 11 - 80535 München Fax (089) 29 40 44 E-Mail [email protected] http://www.bayern.de/Kontakt-.466/index.htm Berlin Klaus Wowereit Regierender Bürgermeister von Berlin Der Senat von Berlin Berliner Rathaus Rathausstraße 15 - 10175 Berlin Fax (030) 90 26-30 19 E-Mail [email protected] http://www.berlin.de/rbmskzl/index.html – 1 – Adressliste – 2 – Adressliste – 1 – Adressliste Brandenburg Matthias Platzeck Ministerpräsident des Landes Brandenburg Staatskanzlei Brandenburg Heinrich-Mann-Allee 107 - 14473 Potsdam Postfach 60 10 51 - 14410 Potsdam Fax (0331) 8 66-13 21 E-Mail [email protected] http://www.stk.brandenburg.de/cms/detail.php/lbm1.c.375532.de Bremen Jens Böhrnsen Präsident des Senats und Bürgermeister der Hansestadt Bremen Senat der Freien Hansestadt -

The German Bundesrat

THE GERMAN BUNDESRAT Last updated on 04/05/2021 http://www.europarl.europa.eu/relnatparl [email protected] Photo credits: German Bundesrat 1. AT A GLANCE The German Basic Law stipulates clearly that "the Federal Republic of Germany is a democratic and social federal state" and that "except as otherwise provided or permitted by this Basic Law, the exercise of state powers and the discharge of state functions is a matter for the Länder". The Bundesrat has a total of 69 full Members and the same number of votes. The Bundesrat is composed of Members of Länder governments and not of directly elected Members. Since elections in the 16 German Länder take place at different times, the political composition and the majority in the Bundesrat often changes. It is in fact the executive power of the Länder, which is represented in the Bundesrat. The Länder governments do not need a formal parliamentary mandate for their voting behaviour for individual acts in the Bundesrat. 2. COMPOSITION Land Population, m Minister-President Votes Parties in government Winfried Kretschmann Baden-Württemberg 11.10 6 Grüne/CDU (Greens-EFA/EPP) (Grüne/Greens-EFA) Bayern 13.12 Markus Söder (CSU/EPP) 6 CSU (EPP)/Freie Wähler Berlin 3.66 Michael Müller (SPD/S&D) 4 SPD/Die Linke/Grüne (S&D/The Left/Greens-EFA) Dietmar Woidke Brandenburg 2.50 4 SPD/CDU/Grüne (S&D/EPP/Greens-EFA) (SPD/S&D) Bremen 0.68 Andreas Bovenschulte (SPD/S&D) 3 SPD/Grüne/Die Linke (S&D/Greens-EFA/The Left ) Hamburg 1.85 Peter Tschentscher, (SPD/S&D) 3 SPD/Grüne (S&D/Greens-EFA) Hessen 6.29 Volker -

Villa Reitzenstein

Villa Reitzenstein Herzlich willkommen in der Villa Reitzenstein Das prächtige Gebäude in Stuttgarter Halbhöhenlage ist Amtssitz des Ministerpräsidenten und zugleich Sitz der Landesregierung und des Staatsministeriums von Baden-Württemberg. Wir laden Sie herzlich ein zu einem virtuellen Rundgang durch dieses Haus, das von der Baronin Helene von Reitzenstein zu Beginn des vorigen Jahrhunderts errichtet wurde und von einem herrlichen Park umgeben ist. Werfen Sie einen Blick in das Innere der Villa und erfahren Sie mehr über den Ort, von dem aus Baden-Württemberg regiert wird. Virtueller Rundgang durch die Villa Reitzenstein www.villa-reitzenstein.de © Staatsministerium Baden-Württemberg Villa Reitzenstein Innenansichten Eingangshalle Durch ein schweres messingbeschlagenes Portal betritt der Besucher die großzügige Eingangshalle der Villa Reitzenstein. Von hier aus erreicht man die Empfangs- und Repräsentationsräume des baden-württembergischen Regierungssitzes. Markant ist das kunstvolle Fußbodenmosaik aus italienischem Marmor. Ein großformatiges Gemälde erinnert an die Erbauerin der Villa, Baronin Helene von Reitzenstein, ein weiteres an ihren Ehemann, Baron Carl von Reitzenstein. In das gusseiserne Geländer entlang der ins Obergeschoss führenden Treppe ist ein Monogramm mit ihren Initialen „HR“ eingearbeitet. Schon die Eingangshalle vermittelt einen Eindruck von der Eleganz der schlossartigen Villa. Im Seitenflur hängen die gemalten Porträts der ehemaligen Ministerpräsidenten Reinhold Maier (1952 - 1953), Hans Filbinger (1966 - 1978), Lothar Späth (1978 - 1991) und Erwin Teufel (1991 - 2005). Virtueller Rundgang durch die Villa Reitzenstein www.villa-reitzenstein.de © Staatsministerium Baden-Württemberg Villa Reitzenstein Runder Saal Im Runden Saal empfängt der baden-württembergische Ministerpräsident Gäste aus nah und fern. Zahlreiche Staatsoberhäupter und königliche Hoheiten standen schon unter dem Kronleuchter der früheren Hausherrin, Baronin von Reitzenstein, und trugen sich in das Gästebuch des Landes ein. -

Neujahrsgruß 1

Neujahrsgruß 1 Martin Rötz Dr. Ulrich Seidel Präsident des Geschäftsführer des Unternehmerverbandes Unternehmerverbandes Rostock und Umgebung e.V. Rostock und Umgebung e.V. Liebe Leser, DIE THEMEN mit Tempo verändern sich auch in unserem Land Wissenschaft, Technik, Wirt- schaft und Wertvorstellungen. Unser Land hat alle Voraussetzungen, mehr Vertrauen in sich selbst zu finden. Die Menschen müssen fest auf Verlässlich- keit bauen können. Netzwerk der guten Taten Das bedeutet zugleich, dass sich ein jeder selbst zum Handeln für die Zukunft Steuerrad e.V. setzt auf Zukunft entscheidet. Es geht darum, tragfähige Lösungen für die Probleme unserer Seite 3 Zeit beizutragen. Unser Verband hat sich dafür im zurückliegenden Jahr stark eingebracht. Dafür danken wir im Namen unseres Vorstandes allen, auf die wir uns in den vergangenen Monaten stützen konnten. Die Beratungs- Rechenschaft und weiterer Kurs angebote, so im Rechtsbereich, bei Finanzierungen und betriebswirtschaft- Fazit der offenen und ordentlichen lichen Fragen einschließlich Sanierungsmanagement wurden nicht nur von Mitgliederversammlung Verbandsmitgliedern stark in Anspruch genommen. Im Fokus standen unter Seite 8 anderem der Ausbau der Kooperationsbeziehungen, Projektarbeiten, die Entwicklung tragfähiger Netzwerke und die Hilfe bei überregionalen Wirt- schaftsaktivitäten. Erfolgsstory in Rostock Im engen Dialog mit der Politik werden wir 2007 weiterhin einen wichtigen Betonteilewerk Rostock GmbH auf dem Beitrag für eine mittelstandfreundliche Wirtschafts- und Arbeitsmarktpolitik skandinvischen Markt leisten. Hierfür haben wir unsere klare Positionierung an Bundesminister Seite 12 Wolfgang Tiefensee übergeben. Forschung, Bildung und Innovationen sind unsere besten Trümpfe im inter- nationalen Wettbewerb und darum mit die wichtigsten Aufgaben der näch- Eurawasser investiert in den sten Jahre. Unser Bildungssystem muss besser werden - daran führt kein Weg Umweltschutz vorbei.