PRISM International Is a Journal of Contemporary Writing, Published Three Times a Year by the University of British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MS Coll 00121

MS. MACEWEN, GWENDOLYN COLL. PAPERS, 1955-1988 121 CHRONOLOGY 1941 Born in Toronto, daughter of Elsie Doris Mitchell and Alick James McEwen. 1948 Published first poem in The Canadian Forum 1955-1959 Attended Western Technical High School 1959 Left school to be a writer: wrote plays and dramatic documentaries for CBC radio which are mainly unpublished, and poetry and fiction. 1959-63 Worked in children’s library Issued Saturnalia, poem, broadside, lithograph. 1961 Published privately Selah and The Drunken Clock, both limited to 100 copies and both books (pamphlets) of poetry 1962 Married and separated from Milton Acorn 1963 Published Julian the Magician, a novel, and The Rising Fire, poems 1965 Received CBC New Canadian Writing contest 1966 Published A Breakfast for Barbarians, poems 1969 Published The Shadow-maker, poems, which won the Governor General’s Award 1970? Published Jewelry: a Poem, a broadside 1971 Published King of Egypt, King of Dreams, a novel Married Nikos Tsingos 1972 Operated the Trojan Horse, a coffee house in Toronto with Nikos Tsingos, a Greek singer to whom she was married for six years Published Noman, a collection of short stories (reprinted 1985) 1 MS. MACEWEN, GWENDOLYN COLL. PAPERS, 1955-1988 121 CHRONOLOGY 1973 Published The Armies of the Moon, poems Received A.J.M. Smith Award 1974 Magic Animals, poems (reprinted 1984) 1976 Published The Fire Eaters, poems 1978 Published Mermaids and Ikons; a Greek Summer, travel recollections of Greece 1979 Published The Trojan Women; a play 1980 Published The Man with three Violins, broadside 1981 Published The Chocolate Moose, a children’s book Published The Trojan Women which contains her version of Euripides’ The Trojan Women and her translation of two poems, “Helen” and “Orestes” by Yannis Ritsos 1982 Published The T.E. -

Notes on Contributors

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Calgary Journal Hosting Notes on Contributors MARGARET ATWOOD was born in Ottawa in 1939 and received de• grees from the University of Toronto and Harvard University. She has taught at a number of Canadian universities and last year was Writer in Residence at the University of Toronto. She won the Governor-General's Award in 1966. Her five books of poems include The Circle Game (1966), The Journals of Susanna Moodie (1970) and Power Politics (1971). She has also written two novels, The Edible Woman (1969), and Surfacing (1972) and a critical book Survival (1972). DOUGLAS BARBOUR lives and works in Edmonton, Alberta. He has four books of postry out, of which the latest is songbook (talon- books, 19731. The others are Land Fall (1971), A Poem as Long as the Highway (1971), and White (1972). S. A. DJWA, Associate Professor, teaches Canadian Literature at Simon Fraser University and is a regular contributor to Cana• dian Literature and the Journal of Canadian Fiction. Professor Djwa has recently completed a book on E. J. Pratt (Copp Clark and McGill-Queen's University Press) and has developed com• puter concordances to fourteen Canadian poets in the prepara• tion of a thematic history of English Canadian poetry. She is now working on an edition of Charles Heavysege's poetry for the University of Toronto Press Literature of Canada Reprint Series. RALPH GUSTAFSON'S eighth book of poems, Fire on Stone, will be published by McClelland & Stewart, Toronto, autumn 1974. -

Imperial Commerce and the Canadian Muse the Hudson’S Bay Company’S Poetic Advertising Campaign of 1966–1972

Michael Ross and Lorraine York Imperial Commerce and the Canadian Muse The Hudson’s Bay Company’s Poetic Advertising Campaign of 1966–1972 In July of 1965, Barbara Kilvert, the Executive Assistant of Public Relations with the Hudson’s Bay Company, kicked off an unusual advertising campaign by buying a poem from Al Purdy. She had come across a review of Cariboo Horses in the May issue of Time magazine, and, in her words, “decided I should make contact.” As she later reminisced, “This was the beginning of it all.” “It all” referred to a promotional venture inaugurated by Purdy’s “Arctic Rhododendrons”—a series of ads featuring “new poems by Canadian poets, with layout design handled by young artists” (Kilvert, Annotation, Purdy Review). Over the next six years, the advertisements appeared in such respected periodicals as Quarry, The Tamarack Review, Canadian Literature, The Malahat Review, Cité Libre, and Liberté. Participants in the ad campaign made for an impressive roster of writers, including, besides Purdy, Margaret Atwood, Earle Birney, Louis Dudek, Joan Finnegan, Phyllis Gotlieb, Ralph Gustafson, D. G. Jones, Gustave Lamarche, Gwendolyn MacEwen, John Newlove, Alden Nowlan, Michael Ondaatje, Fernand Ouellette, P. K. Page, Jean-Guy Pilon, James Reaney, A. J. M. Smith, Raymond Souster, and Miriam Waddington. Focussing on HBC’s use of original works by Canadian poets in three of these journals—Quarry, Tamarack, and Canadian Literature—(See Appendix), this essay assesses the consequences of recontextualizing poems within a commercial frame of reference. Some of those consequences, as we will argue, were positive. Others, however, were troubling; poetic meaning could irresistibly be drawn into the orbit of HBC’s commercial objectives. -

The Masks of D. G. Jones

THE MASKS OF D. G. JONES E.D.Blodgdt "Pour se reconnaître, il faut se traduire" LUBLIC SILENCE surrounding the work of D. G. Jones in Canada is inexorable but not inexplicable. His three books of poetry have emerged and disappeared apparently without complaint against the more stri- dent and ephemeral appeals of the poetry of the past decade in this country. Beside the meteoric flash of such writers as Leonard Cohen and, now, Margaret Atwood, Jones's subtle brilliance seems a pale fire indeed. This is because Jones is a poet who is penetrating with care and delicate concern many of Canada's more troubling aesthetic preoccupations. He is a poet of courage whose surfacing is always deceptive and often misleading in a country where the search for self and heritage can be so exhausting that most poets would prefer to settle for any mode of irony that would both expose the mysterious folly of self-discovery and, also, prevent whatever fulfillment of exploration might be possible. This is the poetry of an imagination that was early formed, and such changes as occur are those of a style deepened only by tragic events.1 It should be remarked, nevertheless, how the centre of Jones's circles of radiation is placed in his first book. As a poet who seems only minimally ready for statement, he enunciated an almost consuming passion in his first poem in Frost On The Sun2 entitled "John Marin". Jones's passion is for art, form and the artist's ambiguous relation to the world present to the eye. -

Gender and the Search for Identity in Gwendolyn Macewan's Julian And

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 1990 Gender and The Search for Identity in Gwendolyn MacEwan’s Julian and Noman Stories Anne Marie Martin Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Anne Marie, "Gender and The Search for Identity in Gwendolyn MacEwan’s Julian and Noman Stories" (1990). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1593. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1593 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gender and The Search for Identity in Gwendolyn MacEwen's Julian and Noman Stories by Anne Marie Martin B.A., York University, 1972 Thesis Submitted to the Department of Religion and Culture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree Wilfrid Laurier University 1990 (S) Anne M. Martin 1990 Property of the Library Wilfrid Laurier University UMI Number: EC56419 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation PuWinhing UMI EC56419 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. -

Gwendolyn Macewen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso

Document generated on 09/23/2021 11:56 p.m. Studies in Canadian Literature Études en littérature canadienne Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso Resurfacing: Women Writing in 1970s Canada Refaire surface : écrivaines canadiennes des années 1970 Volume 44, Number 2, 2019 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1070963ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1070963ar See table of contents Publisher(s) University of New Brunswick, Dept. of English ISSN 0380-6995 (print) 1718-7850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Eso, D. (2019). Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 44(2), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.7202/1070963ar All Rights Reserved ©, 2020 Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit littérature canadienne (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso When they are the work of poets, entertainments, pranks, and hoaxes still fall within the domain of poetry. — François Le Lionnais, Regent, Collège -

Finding Aid : GA 85 Alice Munro/Walter Martin Reference Materials

Special Collections, University of Waterloo Library Finding Aid : GA 85 Alice Munro/Walter Martin reference materials. © Special Collections, University of Waterloo Library GA 85 : Munro/Martin Reference Materials. Special Collections, University of Waterloo Library. Page 1 GA 85 : Munro/Martin Reference Materials Alice Munro/Walter Martin reference materials. - 1968-1994 (originally created 1950- 1994). - 1 m of textual records. - 3 audio cassettes. The collection consists primarily of photocopied material used and annotated by Dr. Walter Martin for his book Alice Munro: Paradox and Parallel published in 1987 by the University of Alberta Press. This includes articles written by Alice Munro, short stories, interviews, biographical and critical articles, as well as paperback copies of her books. Also present is a photocopied proof copy of of Moons of Jupiter, a collection of short stories by A. Munro published by Macmillan of Canada in 1982, sent to Dr. Martin by Douglas Gibson of Macmillan. Additional material includes audio recordings of Alice Munro reading her own works and of an interview done with her by Peter Gzowski for “This Country in the Morning.” The collection is arranged in 5 series: 1. Works by Alice Munro: Published; 2. Works by Alice Munro: Manuscripts (Proofs); 3. Works About Alice Munro; 4. Sound Recordings; 5. Miscellaneous. Title from original finding aid. The Alice Munro collection was donated to Special Collections in 1987 by Dr. Walter Martin of the University of Waterloo Department of English. Finding aid prepared in 1993; revised 1994, 1998 and again in 2010. Several accruals have been made since the initial donation. Series 1 : Works by Alice Munro: Published Works by Alice Munro : published. -

Barnardo Boys Robin Elliott

Document generated on 09/23/2021 9:54 a.m. Intersections Canadian Journal of Music Revue canadienne de musique Barnardo Boys Robin Elliott Volume 28, Number 1, 2007 Article abstract The opera Barnardo Boys, with music by Clifford Crawley and libretto by David URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/019293ar Helwig, was premiered in Kingston, Ontario in May 1982. Inspired by the DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/019293ar example of Benjamin Britten, the creators of the opera regarded community involvement and cooperation between amateurs and professionals as essential See table of contents to the production of the work. There was only one imported professional singer in the cast—Jan Rubes, who was hired to play the lead role of Albert Ashby. Both the libretto and the music of the opera make use of a combination Publisher(s) of pre-existing and newly created source materials. This approach is seen to be typical of a Canadian preference for the genre of documentary opera, which Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités parallels an engagement with historical fiction on the part of Canadian canadiennes novelists. ISSN 1911-0146 (print) 1918-512X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Elliott, R. (2007). Barnardo Boys. Intersections, 28(1), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.7202/019293ar Tous droits réservés © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit des universités canadiennes, 2007 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

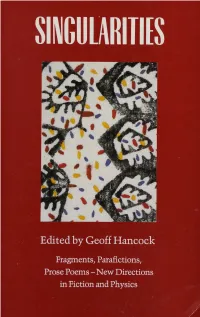

C19 Singularities.Pdf

Singularities 1111111111\\ I \\\\II\ 1\1111\ 1\\1 1111111111 11111111111111111111111 3 9345 00923319 2 CLC SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS PR 9073 846 1990 Singularities . Edited by Geoff Hancoclz Singularities: Fragments, Parafictions, Prose Poems - New Directions in Fiction and Physics Black Moss Press <e> Geoff Hancock 1990 Published by Black Moss Press, 1939 Al ace, Windsor, Ontario, Canada NSW lMS. Black Moss Press books are distributed by Firefly Books, 250 Sparks Avenue, Willowdale, Ontario M2H 2S4 Flnancial assistance toward publication was gratefully received from the Canada Council and the Ontario Arts Council. Cover design: Turkish folk artist Printed and bound in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under ti tie: Singularities ISBN 0-88753-203-9 1. Canadian prose literature !English) - 20th century. I. Hancock, Geoff, 1946- PS8329.S46 1990 C818'.540808 C90-090052-0 PR9194.9.S46 1990 I have the universe all to myself. The universe has me all to itself. - Peter Matthiessen, The Snow Leopard Contents ckno' led ement · w urry Th Atomic tructur of Silence 11 av Godfrey from I Ching Kanada 12 v ndolyn MacEwen An Evening with Grey Owl 16 Erin Moure The Origin of Horses 19 J Ro enblatt from Bride of the Stream 19 Michael Dean An Aural History of Lawns 21 ean o huigin from The Nightmare Alphabet 27 nne zumigalski The Question 29 Karl Jirgen Strappado 30 Lola LeMire Tostevin A Weekend at the Semiotics of Eroticism Colloquium Held at Victoria College 33 maro Kambourelli It Was Not A Dark and Stormy Night 34 George McWhirter Nobody's Notebook 36 Michael Bullock Johannes Weltseele Enters the Garden 45 Claire Harris After the Chinese 50 Patrick Lane Ned Coker's Dream 54 Gay Allison The Slow Gathering Of 60 Eugene McNamara Falling in Place 64 hp Nichol The Toes 69 Rod Willmot from The Ribs of Dragonfl_y 71 Paul Dutton Uncle Rebus Clean Song 73 Fred W ab Elite 78 Daphne Marlatt&. -

Purdy: Man and Poet

PURDY: MAN AND POET George Bowering 1 I. Ν HIS INTRODUCTION to another poet's book, Al Purdy speaks of some possible superficial descriptions of Canadian writers. He says that he himself might be thought of in that mode as "a cynical Canadian nationalist, a lyrical Farley Mowat maybe." It's a disarming suggestion, and a useful one. We should always remember that any single tack we take on a large writer is going to be at least somewhat superficial, and we should especially remember such a thing in Purdy's case, because he makes a habit of surprising a reader or critic with unexpected resources or interests. So I ask you to be careful, too, with my superficialities, such as this one I'll have to begin with: Al Purdy is the world's most Canadian poet. Doug Fetherling, a young Ameri- can refugee who has written that "Al Purdy knows more about writing poetry than anyone else I have ever met, heard or read about,"2 goes on to remark on something I once told him in conversation: "Purdy cannot help but take a lot of Canada with him. He is even so typical looking, as George Bowering points out, that everybody in the interior of British Columbia looks exactly like Purdy." I would like to tell you what Purdy looks like, at least the way this B.C. boy first saw him, but I'll have to begin with an event a half-year before I pressed flesh with him the first time. It was a day or two before Christmas 1962. -

Strength in Numbers Exhibition Catalogue

STRENGTH IN NUMBERS The CanLit Community Exhibition and catalogue by Natalya Rattan and John Shoesmith Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto 27 January to 1 May, 2020 Catalogue and exhibition by Natalya Rattan and John Shoesmith Edited by Marie Korey and Timothy Perry Exhibition designed and installed by Linda Joy Digital photography by Paul Armstrong Catalogue designed by Stan Bevington Catalogue printed by Coach House Press Cover image: Our Land Illustrated in Art and Song . isbn 978-0-7727-6129-3 library and archives canada cataloguing in publication Title: Strength in numbers : the CanLit community / exhibition and catalogue by John Shoesmith and Natalya Rattan. Names: Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, host institution, publisher. | Rattan, Natalya, 1987- author, organizer. | Shoesmith, John, 1969- author, organizer. Description: Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library from January 27, 2020 to May 1, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: Canadiana 20190235780 | ISBN 9780772761293 (softcover) Subjects: LCSH: Canadian literature—19th century—Bibliography—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Canadian literature—20th century—Bibliography—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Canadian literature—21st century— Bibliography—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Authors, Canadian—19th century—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Authors, Canadian—20th century—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Authors, Canadian—21st century— Exhibitions. | LCSH: Publishers and publishing—Canada—History—19th century—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Publishers and publishing—Canada—History—20th century—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Publishers and publishing—Canada—History—21st century—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library—Exhibitions. | LCGFT: Exhibition catalogs. Classification: LCC Z1375 .T56 2020 | DDC 016.8108/0971—dc23 Introduction – Strength in Numbers As any archivist or librarian who works with literary papers will tell you, the pro - cessing of an author’s collection is often an intimate experience. -

Barnardo Boys Robin Elliott

Document generated on 09/27/2021 6:45 p.m. Intersections Canadian Journal of Music Revue canadienne de musique Barnardo Boys Robin Elliott Volume 28, Number 1, 2007 Article abstract The opera Barnardo Boys, with music by Clifford Crawley and libretto by David URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/019293ar Helwig, was premiered in Kingston, Ontario in May 1982. Inspired by the DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/019293ar example of Benjamin Britten, the creators of the opera regarded community involvement and cooperation between amateurs and professionals as essential See table of contents to the production of the work. There was only one imported professional singer in the cast—Jan Rubes, who was hired to play the lead role of Albert Ashby. Both the libretto and the music of the opera make use of a combination Publisher(s) of pre-existing and newly created source materials. This approach is seen to be typical of a Canadian preference for the genre of documentary opera, which Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités parallels an engagement with historical fiction on the part of Canadian canadiennes novelists. ISSN 1911-0146 (print) 1918-512X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Elliott, R. (2007). Barnardo Boys. Intersections, 28(1), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.7202/019293ar Tous droits réservés © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit des universités canadiennes, 2007 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit.