Gender and the Search for Identity in Gwendolyn Macewan's Julian And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MS Coll 00121

MS. MACEWEN, GWENDOLYN COLL. PAPERS, 1955-1988 121 CHRONOLOGY 1941 Born in Toronto, daughter of Elsie Doris Mitchell and Alick James McEwen. 1948 Published first poem in The Canadian Forum 1955-1959 Attended Western Technical High School 1959 Left school to be a writer: wrote plays and dramatic documentaries for CBC radio which are mainly unpublished, and poetry and fiction. 1959-63 Worked in children’s library Issued Saturnalia, poem, broadside, lithograph. 1961 Published privately Selah and The Drunken Clock, both limited to 100 copies and both books (pamphlets) of poetry 1962 Married and separated from Milton Acorn 1963 Published Julian the Magician, a novel, and The Rising Fire, poems 1965 Received CBC New Canadian Writing contest 1966 Published A Breakfast for Barbarians, poems 1969 Published The Shadow-maker, poems, which won the Governor General’s Award 1970? Published Jewelry: a Poem, a broadside 1971 Published King of Egypt, King of Dreams, a novel Married Nikos Tsingos 1972 Operated the Trojan Horse, a coffee house in Toronto with Nikos Tsingos, a Greek singer to whom she was married for six years Published Noman, a collection of short stories (reprinted 1985) 1 MS. MACEWEN, GWENDOLYN COLL. PAPERS, 1955-1988 121 CHRONOLOGY 1973 Published The Armies of the Moon, poems Received A.J.M. Smith Award 1974 Magic Animals, poems (reprinted 1984) 1976 Published The Fire Eaters, poems 1978 Published Mermaids and Ikons; a Greek Summer, travel recollections of Greece 1979 Published The Trojan Women; a play 1980 Published The Man with three Violins, broadside 1981 Published The Chocolate Moose, a children’s book Published The Trojan Women which contains her version of Euripides’ The Trojan Women and her translation of two poems, “Helen” and “Orestes” by Yannis Ritsos 1982 Published The T.E. -

Imperial Commerce and the Canadian Muse the Hudson’S Bay Company’S Poetic Advertising Campaign of 1966–1972

Michael Ross and Lorraine York Imperial Commerce and the Canadian Muse The Hudson’s Bay Company’s Poetic Advertising Campaign of 1966–1972 In July of 1965, Barbara Kilvert, the Executive Assistant of Public Relations with the Hudson’s Bay Company, kicked off an unusual advertising campaign by buying a poem from Al Purdy. She had come across a review of Cariboo Horses in the May issue of Time magazine, and, in her words, “decided I should make contact.” As she later reminisced, “This was the beginning of it all.” “It all” referred to a promotional venture inaugurated by Purdy’s “Arctic Rhododendrons”—a series of ads featuring “new poems by Canadian poets, with layout design handled by young artists” (Kilvert, Annotation, Purdy Review). Over the next six years, the advertisements appeared in such respected periodicals as Quarry, The Tamarack Review, Canadian Literature, The Malahat Review, Cité Libre, and Liberté. Participants in the ad campaign made for an impressive roster of writers, including, besides Purdy, Margaret Atwood, Earle Birney, Louis Dudek, Joan Finnegan, Phyllis Gotlieb, Ralph Gustafson, D. G. Jones, Gustave Lamarche, Gwendolyn MacEwen, John Newlove, Alden Nowlan, Michael Ondaatje, Fernand Ouellette, P. K. Page, Jean-Guy Pilon, James Reaney, A. J. M. Smith, Raymond Souster, and Miriam Waddington. Focussing on HBC’s use of original works by Canadian poets in three of these journals—Quarry, Tamarack, and Canadian Literature—(See Appendix), this essay assesses the consequences of recontextualizing poems within a commercial frame of reference. Some of those consequences, as we will argue, were positive. Others, however, were troubling; poetic meaning could irresistibly be drawn into the orbit of HBC’s commercial objectives. -

PRISM International Is a Journal of Contemporary Writing, Published Three Times a Year by the University of British Columbia

international PRISM Summer, ig66 $1.25 STAFF EDITOR-IN CHIEF Jacob Zilber ASSOCIATE EDITORS Robert Harlow Prose Dorothy Livesay Poetry ART EDITOR David Mayrs ADVISORY EDITOR Jan de Bruyn BUSINESS MANAGER Cherie Smith ILLUSTRATIONS COVER PHOTO David Mayrs ESSAY PHOTO Stanley Read PRINTED BY MORRISS PRINTING COMPANY LTD., VICTORIA, B.C. PRISM international is a journal of contemporary writing, published three times a year by the University of British Columbia. Annual subscriptions are $3.50, single copies $1.25, obtainable by writing to PRISM, c/o Creative Writing, U.B.C, Vancouver 8, Canada. MSS should be sent to the Editors at the same address and must be accom panied by a self-addressed envelope and Canadian or unattached U.S. stamps, or commonwealth or international reply coupons. PRISM international VOLUME SIX NUMBER ONE CONTENTS ESSAY Janus ROY DANIELLS 4 A SELECTION OF POETRY FROM OTHER LANGUAGES Two Poems PAULO BOMFIM 12 (with translations from the Portuguese by DORA PETTINELLA) Ferthalag KARI MAROARSON I4 (with translation by the author from his original Icelandic poem) Langst Hat Die Sonne SIMON GRABOWSKI 16 (with translation by the author from his original German poem) Two Poems GWENDOLYN MACEWEN 17 (with translations by the author from her original "Egyptian hieroglyphs") FROM ENGLAND, SCOTLAND, IRELAND A Merry Month KHADAMBI ASALACHE 20 In the Park JEFF NUTTALL 21 Two Poems MICHAEL HOROVITZ 22 Two Poems A. W. TREES 24 Two Poems LENRIE PETERS 27 Two Poems D. M. THOMAS 29 Two Poems SALLY ROBERTS 31 Three Poems KNUTE SKINNER 33 Two Poems L. M. HERRIGKSON 35 2 FROM AUSTRALIA Death of a God GRACE PERRY 36 FROM GERMANY Three Poems GASTON BART-WILLIAMS 36 FROM THE UNITED STATES South of the Sepulchre JAMES EVANS 42 Timber Blue Haze DUANE MCGINNIS 43 Two Poems DENNIS TRUDELL 44 Survivals BARBARA DRAKE 45 Seven Poems J. -

Gwendolyn Macewen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso

Document generated on 09/23/2021 11:56 p.m. Studies in Canadian Literature Études en littérature canadienne Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso Resurfacing: Women Writing in 1970s Canada Refaire surface : écrivaines canadiennes des années 1970 Volume 44, Number 2, 2019 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1070963ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1070963ar See table of contents Publisher(s) University of New Brunswick, Dept. of English ISSN 0380-6995 (print) 1718-7850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Eso, D. (2019). Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 44(2), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.7202/1070963ar All Rights Reserved ©, 2020 Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit littérature canadienne (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso When they are the work of poets, entertainments, pranks, and hoaxes still fall within the domain of poetry. — François Le Lionnais, Regent, Collège -

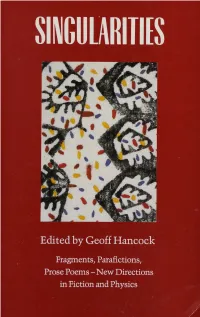

C19 Singularities.Pdf

Singularities 1111111111\\ I \\\\II\ 1\1111\ 1\\1 1111111111 11111111111111111111111 3 9345 00923319 2 CLC SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS PR 9073 846 1990 Singularities . Edited by Geoff Hancoclz Singularities: Fragments, Parafictions, Prose Poems - New Directions in Fiction and Physics Black Moss Press <e> Geoff Hancock 1990 Published by Black Moss Press, 1939 Al ace, Windsor, Ontario, Canada NSW lMS. Black Moss Press books are distributed by Firefly Books, 250 Sparks Avenue, Willowdale, Ontario M2H 2S4 Flnancial assistance toward publication was gratefully received from the Canada Council and the Ontario Arts Council. Cover design: Turkish folk artist Printed and bound in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under ti tie: Singularities ISBN 0-88753-203-9 1. Canadian prose literature !English) - 20th century. I. Hancock, Geoff, 1946- PS8329.S46 1990 C818'.540808 C90-090052-0 PR9194.9.S46 1990 I have the universe all to myself. The universe has me all to itself. - Peter Matthiessen, The Snow Leopard Contents ckno' led ement · w urry Th Atomic tructur of Silence 11 av Godfrey from I Ching Kanada 12 v ndolyn MacEwen An Evening with Grey Owl 16 Erin Moure The Origin of Horses 19 J Ro enblatt from Bride of the Stream 19 Michael Dean An Aural History of Lawns 21 ean o huigin from The Nightmare Alphabet 27 nne zumigalski The Question 29 Karl Jirgen Strappado 30 Lola LeMire Tostevin A Weekend at the Semiotics of Eroticism Colloquium Held at Victoria College 33 maro Kambourelli It Was Not A Dark and Stormy Night 34 George McWhirter Nobody's Notebook 36 Michael Bullock Johannes Weltseele Enters the Garden 45 Claire Harris After the Chinese 50 Patrick Lane Ned Coker's Dream 54 Gay Allison The Slow Gathering Of 60 Eugene McNamara Falling in Place 64 hp Nichol The Toes 69 Rod Willmot from The Ribs of Dragonfl_y 71 Paul Dutton Uncle Rebus Clean Song 73 Fred W ab Elite 78 Daphne Marlatt&. -

Purdy: Man and Poet

PURDY: MAN AND POET George Bowering 1 I. Ν HIS INTRODUCTION to another poet's book, Al Purdy speaks of some possible superficial descriptions of Canadian writers. He says that he himself might be thought of in that mode as "a cynical Canadian nationalist, a lyrical Farley Mowat maybe." It's a disarming suggestion, and a useful one. We should always remember that any single tack we take on a large writer is going to be at least somewhat superficial, and we should especially remember such a thing in Purdy's case, because he makes a habit of surprising a reader or critic with unexpected resources or interests. So I ask you to be careful, too, with my superficialities, such as this one I'll have to begin with: Al Purdy is the world's most Canadian poet. Doug Fetherling, a young Ameri- can refugee who has written that "Al Purdy knows more about writing poetry than anyone else I have ever met, heard or read about,"2 goes on to remark on something I once told him in conversation: "Purdy cannot help but take a lot of Canada with him. He is even so typical looking, as George Bowering points out, that everybody in the interior of British Columbia looks exactly like Purdy." I would like to tell you what Purdy looks like, at least the way this B.C. boy first saw him, but I'll have to begin with an event a half-year before I pressed flesh with him the first time. It was a day or two before Christmas 1962. -

Strength in Numbers Exhibition Catalogue

STRENGTH IN NUMBERS The CanLit Community Exhibition and catalogue by Natalya Rattan and John Shoesmith Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto 27 January to 1 May, 2020 Catalogue and exhibition by Natalya Rattan and John Shoesmith Edited by Marie Korey and Timothy Perry Exhibition designed and installed by Linda Joy Digital photography by Paul Armstrong Catalogue designed by Stan Bevington Catalogue printed by Coach House Press Cover image: Our Land Illustrated in Art and Song . isbn 978-0-7727-6129-3 library and archives canada cataloguing in publication Title: Strength in numbers : the CanLit community / exhibition and catalogue by John Shoesmith and Natalya Rattan. Names: Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, host institution, publisher. | Rattan, Natalya, 1987- author, organizer. | Shoesmith, John, 1969- author, organizer. Description: Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library from January 27, 2020 to May 1, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: Canadiana 20190235780 | ISBN 9780772761293 (softcover) Subjects: LCSH: Canadian literature—19th century—Bibliography—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Canadian literature—20th century—Bibliography—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Canadian literature—21st century— Bibliography—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Authors, Canadian—19th century—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Authors, Canadian—20th century—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Authors, Canadian—21st century— Exhibitions. | LCSH: Publishers and publishing—Canada—History—19th century—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Publishers and publishing—Canada—History—20th century—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Publishers and publishing—Canada—History—21st century—Exhibitions. | LCSH: Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library—Exhibitions. | LCGFT: Exhibition catalogs. Classification: LCC Z1375 .T56 2020 | DDC 016.8108/0971—dc23 Introduction – Strength in Numbers As any archivist or librarian who works with literary papers will tell you, the pro - cessing of an author’s collection is often an intimate experience. -

“Deep in Mines of Old Belief”: Gnosticism in Modern Canadian Literature

“Deep in Mines of Old Belief”: Gnosticism in Modern Canadian Literature by Ryan Edward Miller M.A. (English), Simon Fraser University, 2001 B.A. (English), University of British Columbia, 1997 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Ryan Edward Miller 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for "Fair Dealing." Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Ryan Edward Miller Degree: Doctor of Philosophy, English Title of Thesis: “Deep In Mines of Old Belief”: Modern Gnosticism in Modern Canadian Literature Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Carolyn Lesjak Associate Professor & Graduate Chair Department of English ______________________________________ Dr. Kathy Mezei, Senior Supervisor Professor Emerita, Department of Humanities ______________________________________ Dr. Sandra Djwa, Supervisor Professor Emerita, Department of English ______________________________________ Dr. Christine Jones, Supervisor Senior Lecturer, Department of Humanities ______________________________________ Dr. Eleanor Stebner, Internal Examiner Associate Professor & Woodsworth Chair, Department of Humanities ______________________________________ -

Margaret Atwood Ultimately More Cost-Effective Option I Don’T Prize-Winning Novelist Believe That Books in Their More Familiar Form Are in Any Real Danger’

BOEKWÊRELD information. Why? Firstly cost. Basically it willing to pay for the privilege. Socio- for printed books, are already limited so with puts publishing within reach of anyone who economic conditions also play a role. the current cost of eBooks it has no immedi- can write. There is very little cost involved ate future in libraries. in the creation of an eBook, it is deliverable Future of eBooks anywhere in the world, it can be copy pro- There is no doubt that the printed book Conclusion tected so that no one can steal the contents, will - slowly - give way to electronic book As new technology makes eBooks easier to and the cost to the end user is much less publishing, which has the potential to make read, more portable and more affordable than a printed book. (Mousaion, 2001). books more affordable and more avail- there may be a growing trend towards this Electronic publishing can be an attractive able. Currently this development is slowed medium. But, in my opinion, for now the alternative for new writers who are by high eBook prices, bad eBook-reader good old paperback and its hardcover coun- frustrated by the difficulty of breaking into systems and a lack of eBook quality control. terpart are safe and although the eBook has the print market, or for established writers In short: if you buy a book at the bookstore, its place, people around the world will still who want to write in a genre or on a you can be sure that the provincial viability, curl up in front of the fire place with a good subject that does not interest their print the quality, its possibilities in the market book made of real paper (for the time being publishers or for writers with a blacklist of place, et cetera, has been properly re- at least). -

Rosemary Sullivan

Rosemary Sullivan 2008 Trudeau Fellow, University of Toronto biography Rosemary Sullivan is an award-winning writer, a journalist, a Canada Research Chair at the University of Toronto in creative non-fiction and biographical studies, and the founding director of the MA pro- gram in English in the field of creative writing, who has taught at universities in France, India and Canada. Her recent book, Villa Air- Bel: World War II, Escape and a House in Marseille (HarperCollins) won the Canadian Jewish Books Yad Vashem Award in Holocaust History/Scholarship in 2007. It was published in Canada, the United States, England, Spain, Brazil, the Czech Republic and Italy. She is the author of 12 books, including The Guthrie Road (2009); Cuba: Grace Under Pressure, with photographs by Malcolm David Batty (2003); Labyrinth of Desire: Women, Passion, and Romantic Obsession (2001), published in Canada, the United States, England, Spain, and Latin America; and the national bestseller The Red Shoes: Margaret Atwood Starting Out (1998). Her 1995 biography Shadow Maker: The Life of Gwendolyn MacEwen won the Governor General’s Award for Non-Fiction, the Canadian Author’s Association Literary Award for Non-Fiction, the University of British Columbia’s Medal for Canadian Biography, and the City of Toronto Book Award and was nominated for the Trillium Book Award. It became the basis for Brenda Longfellow’s award-winning documentary Shadow Maker (1998). Sullivan’s first biography, By Heart: Elizabeth Smart/A Life (1991), was nominated for the Governor General’s Award for Non- Fiction. Her first poetry collection The Space a Name Makes (1986) won the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award. -

The Heart Still Singing: Raymond Souster at 82

The Heart Still Singing: Raymond Souster at 82 SCL/ÉLC INTERVIEW BY TONY TREMBLAY N 1935, A YOUNG POET NAMED RAYMOND SOUSTER started appear- ing in Toronto newspapers. Almost seventy years (and some fifty I volumes) later, he is still active. Oberon Press will be bringing out his newest collection, 21 Poems, in the spring of 2003. In the span of those sixty-eight years, Ray Souster has been intimately connected to many of the major developments in modern poetry in this country, and he has known and published most of the major poets in North America. He was on hand to witness the first waves of literary modernism hit the shore in the pages of New Provinces (1936), reading Robert Finch, F.R. Scott, and A.J.M. Smith as an admiring teenager. He was also present, this time more integrally, when John Sutherland, Louis Dudek, and Irving Layton carried the modernist project further with the publication of First Statement (1942), Canada’s first truly avant-garde literary magazine. He was so impressed with Sutherland’s magazine that he started his own, Direction (1943), the first of four. A few years later, he became one-third of the sec- ond-generation modernist triumvirate in Canada. With Dudek and Layton, he appeared in the pages of Cerberus and launched Contact, a magazine and small-press initiative that revolutionized Canadian poetry, publishing most of the major poets of the 1950s and 1960s. During those decades, he also introduced Canadian poets to the larger world, opening vital channels with the Black Mountain and City Lights poets appearing in Cid Corman’s magazine Origin. -

Biographical Influence in Canadian Literature

In compliance with the Canadian Privacy Legislation some supporting forms may have been removed from this dissertation. While these forms may be included in the document page count, their removal does not represent any loss of content from the dissertation. POSTHUMOUS PRAISE BIOGRAPHICAL INFLUENCE IN CANADIAN LITERATURE By RICHARD ALMONTE, B.A., B.ED., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Richard Almonte, September 2003 POSTHUMOUS PRAISE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2003) McMaster University (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Posthumous Praise: Biographical Influence in Canadian Literature AUTHOR: Richard Almonte, B.A. (Toronto), B.Ed. (Western), M.A. (Concordia) SUPERVISOR: Professor James King NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 250 .. \\ Abstract This dissertation explores the phenomenon whereby a number of deceased Canadian women writers have had their lives utilized in subsequent works of fiction, drama, poetry, film, and biography. The dissertation gives this phenomenon a name-biographical influence-and argues that it represents a challenge to traditional literary canonicity in the Canadian context. Whereas literary canonicity has traditionally been the domain ofliterature professors, the phenomenon of biographical influence may be read as a writer-enacted substitution for traditional canonicity. This writer-enacted canon is comprised of literary heroines who have been elevated to their status not, as is traditional, because of the value oftheir work. Rather, entry to this new canon is reserved for writers whose lives often come close to eclipsing the value ascribed to their work. This is an ironic canonicity that valorizes the writer's life, while claiming to valorize the writer's work.