Biographical Influence in Canadian Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Graves Remembered by Jay Macpherson (1931–2012) Dunstan Ward

‘An Immensely Happy Time’: Robert Graves Remembered by Jay Macpherson (1931–2012) Dunstan Ward Eighteen months before her death in March 2012, the distinguished Canadian poet and scholar Jay Macpherson made a return visit to Mallorca, where in 1952 she had met Robert Graves, who so admired her poems that he published her first book himself under his Seizin Press imprint. It was William Graves who suggested at the end of January 2010 that I should try and persuade Professor Macpherson to come to the Tenth Robert Graves Conference in Palma and Deyá that July. ‘She was in Deyá on and off from the early to the late 1950s,’ he wrote. ‘I’ve never seen a copy of Nineteen Poems. I think only she and Terence Hards were given the honour of a Seizin publication.’ I had once spoken briefly with this almost legendary figure, at the Robert Graves Centenary Conference at Oxford in 1995, when Beryl Graves introduced us. Now I wrote to the University of Toronto inviting her to take part in a poetry reading at the conference in Mallorca. I also said that William and I were wondering if she might be prepared to give an interview, in which she could talk about her relationship with Robert Graves and his work. Jay Macpherson’s email reply came two days later: Monday 8 February 2010 Well, yes, tentatively--that is, I have commitments to a sick friend whom I can’t leave without some difficult arranging; but had been hoping to do just that for at least a bit of this summer. -

MS Coll 00121

MS. MACEWEN, GWENDOLYN COLL. PAPERS, 1955-1988 121 CHRONOLOGY 1941 Born in Toronto, daughter of Elsie Doris Mitchell and Alick James McEwen. 1948 Published first poem in The Canadian Forum 1955-1959 Attended Western Technical High School 1959 Left school to be a writer: wrote plays and dramatic documentaries for CBC radio which are mainly unpublished, and poetry and fiction. 1959-63 Worked in children’s library Issued Saturnalia, poem, broadside, lithograph. 1961 Published privately Selah and The Drunken Clock, both limited to 100 copies and both books (pamphlets) of poetry 1962 Married and separated from Milton Acorn 1963 Published Julian the Magician, a novel, and The Rising Fire, poems 1965 Received CBC New Canadian Writing contest 1966 Published A Breakfast for Barbarians, poems 1969 Published The Shadow-maker, poems, which won the Governor General’s Award 1970? Published Jewelry: a Poem, a broadside 1971 Published King of Egypt, King of Dreams, a novel Married Nikos Tsingos 1972 Operated the Trojan Horse, a coffee house in Toronto with Nikos Tsingos, a Greek singer to whom she was married for six years Published Noman, a collection of short stories (reprinted 1985) 1 MS. MACEWEN, GWENDOLYN COLL. PAPERS, 1955-1988 121 CHRONOLOGY 1973 Published The Armies of the Moon, poems Received A.J.M. Smith Award 1974 Magic Animals, poems (reprinted 1984) 1976 Published The Fire Eaters, poems 1978 Published Mermaids and Ikons; a Greek Summer, travel recollections of Greece 1979 Published The Trojan Women; a play 1980 Published The Man with three Violins, broadside 1981 Published The Chocolate Moose, a children’s book Published The Trojan Women which contains her version of Euripides’ The Trojan Women and her translation of two poems, “Helen” and “Orestes” by Yannis Ritsos 1982 Published The T.E. -

IN the WHALE's BELLY Jay Macpherson's Poetry

IN THE WHALE'S BELLY Jay Macpherson's Poetry Suniti Namjoshi J"A.Y MACPHERSON'S FIRST MAJOR BOOK of poems, The Boat- man, was published in 1957 by Oxford University Press and then republished in 1968 with the addition of sixteen new poems.1 Her second book of poems, Wel- coming Disaster, appeared in 1974. No discussion of modern Canadian poetry is complete without at least a mention of Jay Macpherson's name, but the only article on her poetry that I have come across is the one by James Reaney, "The Third Eye: Jay Macpherson's The Boatman," which appeared in Canadian Literature in 1960. Fortunately, that article is almost definitive. Superficially, there seem to be some obvious differences between The Boatman and Welcoming Disaster. The second in some ways seems much "simpler." It is my purpose here to explore some of the similarities and differences with the aid of Jay Macpher- son's other writings,2 which include two theses, two lectures, and a children's text on classical mythology. As Reaney makes clear, the central myth of The Boatman is that of the ark. The ark appears to contain us, as though we were trapped in the belly of some monstrous creature, and its contents appear to be hopelessly miscellaneous; but properly perceived, Man, in fact, contains the ark, and its contents are ordered: In a poem entitled "The Anagogic Man" we are presented with ... the figure of a sleeping Noah whose head contains all creation ... The whole collection of poems requires the reader to transfer himself from the sleep our senses keep to Noah's sleep, and from Noah's sleep eventually to the first morning in Paradise. -

The Anxiety of Influence: a Theory of Poetry Free

FREE THE ANXIETY OF INFLUENCE: A THEORY OF POETRY PDF Prof. Harold Bloom | 208 pages | 03 Jul 1997 | Oxford University Press Inc | 9780195112214 | English | New York, United States The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry - Harold Bloom - Google книги Professor Bloom Yale; author of Blake's Apocalypse,and Yeats, interprets modern poetic history — the history of poetry in a Cartesian climate — in terms of Freud's "family romance After graduating from Yale, Bloom remained there The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry a teacher, and was made Sterling Professor of Humanities in Bloom's theories have changed the way that critics think of literary tradition and has also focused his attentions on history and the Bible. He has written over twenty books and edited countless others. He is one of the most famous critics in the world and considered an expert in many fields. In he became a founding patron of Ralston College, a new institution in Savannah, Georgia, that focuses on primary texts. Harold Bloom. Harold Bloom's The Anxiety of Influence has cast its own long shadow of influence since it was first published in Through an insightful study of Romantic poets, Bloom puts forth his central vision of the relations between tradition and the individual artist. Although Bloom was never the leader of any critical "camp," his argument that all literary texts are a response to those that precede them had an enormous impact on the practice of deconstruction and poststructuralist literary theory in this country. The book remains a central work The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry criticism for all students of literature and has sold over 17, copies in paperback since Written in a moving personal style, anchored by concrete examples, and memorably quotable, Bloom's book maintains that the anxiety of influence cannot be evaded-- neither by poets nor by responsible readers and critics. -

Index to the Tamarack Review

The Tamarack Review ROBERT WEAVER, IVON M. OWEN, WILLIAM TOYE WILLIAM KILBOURNE, JOHN ROBERT COLOMBO, KILDARE DOBBS AND JANIS RAPOPORT Issue 1 Issue 21 Issue 41 Issue 62 Issue 2 Issue 22 Issue 42 Issue 63 Issue 3 Issue 23 Issue 43 Issue 64 Issue 4 Issue 24 Issue 44 Issue 65 Issue 5 Issue 25 Issue 45 Issue 66 Issue 6 Issue 26 Issue 46 Issue 67 Issue 7 Issue 27 Issue 47 Issue 68 Issue 8 Issue 28 Issue 48 Issue 69 Issue 9 Issue 29 Issue 49 Issue 70 Issue 10 Issue 30 Issue 50-1 Issue 71 Issue 11 Issue 31 Issue 52 Issue 72 Issue 12 Issue 32 Issue 53 Issue 73 Issue 13 Issue 33 Issue 54 Issue 74 Issue 14 Issue 34 Issue 55 Issue 75 Issue 15 Issue 35 Issue 56 Issue 76 Issue 16 Issue 36 Issue 57 Issue 77-8 Issue 17 Issue 37 Issue 58 Issue 79 Issue 18 Issue 38 Issue 59 Issue 80 Issue 19 Issue 39 Issue 60 Issue 81-2 Issue 20 Issue 40 Issue 61 Issue 83-4 ISBN 978-1-55246-804-3 The Tamarack Review Index Volume 81-84 “109 Poets.” Rosemary Aubert article 81- Bickerstaff 83-84:40 82:94-99 “Concerning a Certain Thing Called “A Deposition” J.D. Carpenter poem 81- Houths” Robert Priest poem 81- 82:8-9 82:68-69 “A Mansion in Winter” Daniel David “Control Data” Chris Dewdney, poem, Moses poem 81-82:30-31 81-82:21 “Above an Excavation” Al Moritz poem “Croquet” Al Moritz poem 83-84:98 83-84:99 “Daybook” Ken Cathers poem 81-82:10- “Again” Al Moritz poem 83-84:101 11 “Air Show” J.D. -

Untitled and Unnumbered Poems of "The Fire" Are Musically Structured Into Four Distinct Movements

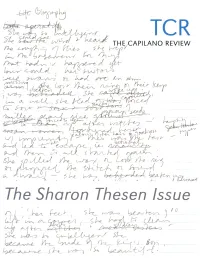

...poetry being the good bacteria of language . .. -SHARON THESEN EDITOR Jenny Penberthy EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Andrea Actis THE CAPILANO PRESS Colin Browne, Pierre Coupey, Roger Farr, SOCIETY BOARD Brook Houglum, Crystal Hurdle, Andrew Klobucar, Elizabeth Rains, George Stanley, Sharon Thesen CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Clint Burnham, Erin Moure, Lisa Robertson FOUNDING EDITOR Pierre Coupey DESIGN CONSULTANT Jan Westendorp WEBSITE DESIGN James Thomson The Capilano Review is published by The Capilano Press Society. Canadian subscription rates for one year are $25 GST included forindividuals. Institutional rates are $30 plus GST. Outside Canada, add $5 and pay in U.S. funds. Address correspondence to The Capilano Review, 2055 Purcell Way, North Vancouver, BC V?J 3H5. Subscribe online at www.thecapilanoreview.ca For our submission guidelines, please see our website or mail us an SASE. Submissions must include an SASE with Canadian postage stamps, international reply coupons, or funds for return postage or they will not be considered-do not use U.S. postage on the SASE. The Capilano Review does not take responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts, nor do we consider simultaneous submissions or previously published work; e-mail submissions are not considered. Copyright remains the property of the author or artist. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the author or artist. Please contact accesscopyright.ca for permissions. The Capilano Review gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of Capilano College and the Canada Council forthe Arts. We acknowledge the financialsupport of the Government of Canada through the Canada Magazines Fund toward our editorial and production costs. The Capilano Review is a member of Magazines Canada (formerly CMPA), the BC Association of Magazine Publishers, and the Alliance forArts and Culture (Vancouver). -

Imperial Commerce and the Canadian Muse the Hudson’S Bay Company’S Poetic Advertising Campaign of 1966–1972

Michael Ross and Lorraine York Imperial Commerce and the Canadian Muse The Hudson’s Bay Company’s Poetic Advertising Campaign of 1966–1972 In July of 1965, Barbara Kilvert, the Executive Assistant of Public Relations with the Hudson’s Bay Company, kicked off an unusual advertising campaign by buying a poem from Al Purdy. She had come across a review of Cariboo Horses in the May issue of Time magazine, and, in her words, “decided I should make contact.” As she later reminisced, “This was the beginning of it all.” “It all” referred to a promotional venture inaugurated by Purdy’s “Arctic Rhododendrons”—a series of ads featuring “new poems by Canadian poets, with layout design handled by young artists” (Kilvert, Annotation, Purdy Review). Over the next six years, the advertisements appeared in such respected periodicals as Quarry, The Tamarack Review, Canadian Literature, The Malahat Review, Cité Libre, and Liberté. Participants in the ad campaign made for an impressive roster of writers, including, besides Purdy, Margaret Atwood, Earle Birney, Louis Dudek, Joan Finnegan, Phyllis Gotlieb, Ralph Gustafson, D. G. Jones, Gustave Lamarche, Gwendolyn MacEwen, John Newlove, Alden Nowlan, Michael Ondaatje, Fernand Ouellette, P. K. Page, Jean-Guy Pilon, James Reaney, A. J. M. Smith, Raymond Souster, and Miriam Waddington. Focussing on HBC’s use of original works by Canadian poets in three of these journals—Quarry, Tamarack, and Canadian Literature—(See Appendix), this essay assesses the consequences of recontextualizing poems within a commercial frame of reference. Some of those consequences, as we will argue, were positive. Others, however, were troubling; poetic meaning could irresistibly be drawn into the orbit of HBC’s commercial objectives. -

Gender and the Search for Identity in Gwendolyn Macewan's Julian And

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 1990 Gender and The Search for Identity in Gwendolyn MacEwan’s Julian and Noman Stories Anne Marie Martin Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Anne Marie, "Gender and The Search for Identity in Gwendolyn MacEwan’s Julian and Noman Stories" (1990). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1593. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1593 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gender and The Search for Identity in Gwendolyn MacEwen's Julian and Noman Stories by Anne Marie Martin B.A., York University, 1972 Thesis Submitted to the Department of Religion and Culture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree Wilfrid Laurier University 1990 (S) Anne M. Martin 1990 Property of the Library Wilfrid Laurier University UMI Number: EC56419 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation PuWinhing UMI EC56419 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. -

Pat Lowther Research Collection (Msc-210)

Simon Fraser University Special Collections and Rare Books Finding Aid - Toby Brooks - Pat Lowther research collection (MsC-210) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.1 Printed: July 03, 2019 Language of description: English Simon Fraser University Special Collections and Rare Books W.A.C. Bennett Library - Room 7100 Simon Fraser University 8888 University Drive Burnaby BC Canada V5A 1S6 Telephone: 778.782.8842 Email: [email protected] http://atom.archives.sfu.ca/index.php/toby-brooks-fonds Toby Brooks - Pat Lowther research collection Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Series descriptions .......................................................................................................................................... -

Ethics and the Biographical Artifact: Doing Biography in the Academy Today Christine Wiesenthal University of Alberta

Ethics and the Biographical Artifact: Doing Biography in the Academy Today Christine Wiesenthal University of Alberta , “” in the most mundane sense Tof the phrase have come sharply, even painfully, into focus for me. is is simply to confess that, at the end of several years of researching and writing my recent biography, e Half-Lives of Pat Lowther, I have yet to confront the truly terrible job of cleaning up my study, which is still cluttered to overflowing with all of those “things”—those physical rem- nants and records—that we tend to collect in the process of attempting to “reconstruct” a “life.” It’s a mess that calls to mind Mary Shelley’s “filthy workshop of creation.” And as I’ve been tripping over the accordion files, maps, photographs, and so forth that litter my study floor, I’ve also been grappling with the question of what to do with all of this material now that the book is done: now that the work is, in deed, a “fact”—“a thing done.” As opposed to a “fact,” “a thing done,” artifact of course connotes instead “a thing made”—“an artificial product” of “human art and works- manship.”¹ Interestingly, the records the first usage of the word by the British poet Coleridge, who in deployed it in a long and loving epistolary disquisition on the “ideal qualities and properties” of a good Art -i -fakt: L arte, by skill + factum neut. of factus, pp of facere, “to do” more at arm, do. , nd ed. ESC .– (June/September ): – Wiesenthal.indd 63 2/24/2008, 3:56 PM inkstand. -

PRISM International Is a Journal of Contemporary Writing, Published Three Times a Year by the University of British Columbia

international PRISM Summer, ig66 $1.25 STAFF EDITOR-IN CHIEF Jacob Zilber ASSOCIATE EDITORS Robert Harlow Prose Dorothy Livesay Poetry ART EDITOR David Mayrs ADVISORY EDITOR Jan de Bruyn BUSINESS MANAGER Cherie Smith ILLUSTRATIONS COVER PHOTO David Mayrs ESSAY PHOTO Stanley Read PRINTED BY MORRISS PRINTING COMPANY LTD., VICTORIA, B.C. PRISM international is a journal of contemporary writing, published three times a year by the University of British Columbia. Annual subscriptions are $3.50, single copies $1.25, obtainable by writing to PRISM, c/o Creative Writing, U.B.C, Vancouver 8, Canada. MSS should be sent to the Editors at the same address and must be accom panied by a self-addressed envelope and Canadian or unattached U.S. stamps, or commonwealth or international reply coupons. PRISM international VOLUME SIX NUMBER ONE CONTENTS ESSAY Janus ROY DANIELLS 4 A SELECTION OF POETRY FROM OTHER LANGUAGES Two Poems PAULO BOMFIM 12 (with translations from the Portuguese by DORA PETTINELLA) Ferthalag KARI MAROARSON I4 (with translation by the author from his original Icelandic poem) Langst Hat Die Sonne SIMON GRABOWSKI 16 (with translation by the author from his original German poem) Two Poems GWENDOLYN MACEWEN 17 (with translations by the author from her original "Egyptian hieroglyphs") FROM ENGLAND, SCOTLAND, IRELAND A Merry Month KHADAMBI ASALACHE 20 In the Park JEFF NUTTALL 21 Two Poems MICHAEL HOROVITZ 22 Two Poems A. W. TREES 24 Two Poems LENRIE PETERS 27 Two Poems D. M. THOMAS 29 Two Poems SALLY ROBERTS 31 Three Poems KNUTE SKINNER 33 Two Poems L. M. HERRIGKSON 35 2 FROM AUSTRALIA Death of a God GRACE PERRY 36 FROM GERMANY Three Poems GASTON BART-WILLIAMS 36 FROM THE UNITED STATES South of the Sepulchre JAMES EVANS 42 Timber Blue Haze DUANE MCGINNIS 43 Two Poems DENNIS TRUDELL 44 Survivals BARBARA DRAKE 45 Seven Poems J. -

Gwendolyn Macewen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso

Document generated on 09/23/2021 11:56 p.m. Studies in Canadian Literature Études en littérature canadienne Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso Resurfacing: Women Writing in 1970s Canada Refaire surface : écrivaines canadiennes des années 1970 Volume 44, Number 2, 2019 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1070963ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1070963ar See table of contents Publisher(s) University of New Brunswick, Dept. of English ISSN 0380-6995 (print) 1718-7850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Eso, D. (2019). Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 44(2), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.7202/1070963ar All Rights Reserved ©, 2020 Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit littérature canadienne (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso When they are the work of poets, entertainments, pranks, and hoaxes still fall within the domain of poetry. — François Le Lionnais, Regent, Collège