Purdy: Man and Poet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Purdy-Al-2071A.Pdf

AL PURDY PAPERS PRELIMINARY INVENTORY Table of Contents Biographical Sketch .................................. page 1 Provenance •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 0 ••••••••• page 1 Restrictions ..................................... 0 ••• page 1 General Description of Papers ••••••••••••••••••••••• page 2 Detailed Listing of Papers ............................ page 3 Appendix •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• page 52 • AL f'lJRDY PAPEllS PRELnlI~ARY INVENroRY BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Al Purdy was born in 1918 in Hoo ler, Ontario . His formal education eeied after only two years of high scnool. He spent the next years of his life wandering from job to job, spending the war years with the R.C.A.F. He spent some time on the West Coast and in 1956 be returned east.. He has received Canada Council Grants wbich enabled him to t ravel into the interior of British Columbia (1960) and to Baffin Island (1965) and a tour of Greece (1967). He has published 10 books of poetry and edited three books, and has contributed to various magazines. His published books are; The En ch~"ted Echo (1944) Pr. ssed 00 Sand (1955) Emu Remember (1957) Tne Grafte So Longe to Lerne (1959) r Poems for all the AnnetteG (1962) The Blur in Between (1963 earihoo Horses (1965) Covernor Ceneral'5 weda1 North of Summer (1967) ·Wild Grape Wine (1968) The New Romans (1968) Fifteeo Wind. (1969) l've Tasted My Blood. Selected poems of Mil ton Acorn (1969) He has also reviel-.'ed many new books and h&s written some scripts for the C.B.C. PROVENANCE These paperG were purchased from Al Purdy witb fun~from The Chancellor Richardson Memorial Fu.."'\d in 1969. RESTRICTIONS None. -

MS Coll 00121

MS. MACEWEN, GWENDOLYN COLL. PAPERS, 1955-1988 121 CHRONOLOGY 1941 Born in Toronto, daughter of Elsie Doris Mitchell and Alick James McEwen. 1948 Published first poem in The Canadian Forum 1955-1959 Attended Western Technical High School 1959 Left school to be a writer: wrote plays and dramatic documentaries for CBC radio which are mainly unpublished, and poetry and fiction. 1959-63 Worked in children’s library Issued Saturnalia, poem, broadside, lithograph. 1961 Published privately Selah and The Drunken Clock, both limited to 100 copies and both books (pamphlets) of poetry 1962 Married and separated from Milton Acorn 1963 Published Julian the Magician, a novel, and The Rising Fire, poems 1965 Received CBC New Canadian Writing contest 1966 Published A Breakfast for Barbarians, poems 1969 Published The Shadow-maker, poems, which won the Governor General’s Award 1970? Published Jewelry: a Poem, a broadside 1971 Published King of Egypt, King of Dreams, a novel Married Nikos Tsingos 1972 Operated the Trojan Horse, a coffee house in Toronto with Nikos Tsingos, a Greek singer to whom she was married for six years Published Noman, a collection of short stories (reprinted 1985) 1 MS. MACEWEN, GWENDOLYN COLL. PAPERS, 1955-1988 121 CHRONOLOGY 1973 Published The Armies of the Moon, poems Received A.J.M. Smith Award 1974 Magic Animals, poems (reprinted 1984) 1976 Published The Fire Eaters, poems 1978 Published Mermaids and Ikons; a Greek Summer, travel recollections of Greece 1979 Published The Trojan Women; a play 1980 Published The Man with three Violins, broadside 1981 Published The Chocolate Moose, a children’s book Published The Trojan Women which contains her version of Euripides’ The Trojan Women and her translation of two poems, “Helen” and “Orestes” by Yannis Ritsos 1982 Published The T.E. -

Th€ Living Mosaic

$1.2$ pw C0Py Autumn, ig6g TH€ LIVING MOSAIC Articles BY PHYLLIS GROSSKURTH, JOHN OWER, MAX DORSINVILLE, SUSAN JACKELj MARGARET MORRISS Special Feature COMPILED BY JOHN REEVES, WITH POEMS BY YAR SLAVUTYCH, HENRIKAS NAGYS, WALTER BAUER, Y. Y. SEGAL, ZOFJA BOHDANOWICZ, ROBERT ZEND, ARVED VDRLAID, INGRIDE VIKSNA, LUIGI ROMEO, PADRAIG BROIN Reviews BY RALPH G USTAFSON , WARREN TALLMAN, JACK WARWICK, GEORGE BOWERING, DOUGLAS BARBOUR, VI C T O R HOAR, K E AT H F R ASE R , CLARA THOMAS, G AR Y GEDDES, ANN SADDLEMYER, G E O R G E WO O D C O C K , YAR SLAVUTYCH, W. F. HALL A QUARTERLY OF CRITICISM AND R6VI6W AN ABSENCE OF UTOPIAS LIITERATURES are defined as much by their lacks as by their abundances, and it is obviously significant that in the whole of Canadian writing there has appeared only one Utopian novel of any real interest; it is significant in terms of our society as much as of our literature. The book in question is A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder. It was written in the 1870's and published in 1888, eight years after the death of its author, James de Mille, a professor of English at Dalhousie, who combined teach- ing with the compulsive production of popular novels ; by the time of his death at the age of 46 he had already thirty volumes to his credit, but only A Strange Manuscript has any lasting interest. It has been revived as one of the reprints in the New Canadian Library (McClelland & Stewart, $2.75), with an introduction by R. -

Selected Poems by Merle Amodeo

Canadian Studies. Language and Literature MARVIN ORBACH, MERLE AMODEO: CANADIAN POETS, UNIVERSAL POETS M.Sc. Miguel Ángel Olivé Iglesias. Associate Professor. University of Holguín, Cuba Abstract This paper aims at revealing universality in Marvin Orbach, an outstanding Canadian book collector and poet, and Merle Amodeo, an exquisite Canadian poet and writer. Orbach´s poems were taken from Redwing, book published by CCLA Hidden Brook Press, Canada in 2018; and Amodeo´s poems from her book After Love, Library of Congress, USA, 2014. Thus, the paper unveils for the general reader the transcendental scope of these two figures of Canadian culture. In view of the fact that they are able to recreate and memorialize their feelings and contexts where they live, and show their capacities to discern beyond the grid of nature, society and human experience, directly and masterfully exposing them, it can be safely stated that both Orbach and Amodeo reach that point where what is singular in them acquires universality, and in return what is universal crystallizes in their singularity. Key Words: universality, Orbach, Redwing, Amodeo, After Love Introduction My connection with universal poetry began during my college years. I enjoyed great English and American classics so much that I even memorized many of their poems. It proved very useful later in my professional career, as I would read excerpts from poems to my students in class. Canada, and Canadian poets, had less presence on the curricular map at the time. Fortunately, I had the chance to become acquainted with Canadian poetry through the Canada Cuba Literary Alliance (CCLA), founded by Richard and Kimberley Grove back in 2004. -

Heritage Fair Projects - Guide to Sources

Public Archives and Records Office of PEI P.O. Box 1000, Charlottetown Prince Edward Island C1A 7M4 (902) 368-4290 fax (902) 368-6327 www.gov.pe.ca/cca (Click Public Archives & Records Office) HERITAGE FAIR PROJECTS - GUIDE TO SOURCES GUIDELINES The Heritage Fair is meant to develop and increase awareness and interest in Canadian history. Your project must have a Canadian theme such as history, geography or heritage whether it is local, national or international. Your teacher will also have certain guidelines which you will need to follow. This booklet has been created to facilitate research for Heritage Fair projects. This guide contains research tips, sources of information, and sample topics. RESEARCH TIPS Getting started Identify a topic. This should be something of interest to you. Be as specific as possible, but be prepared to broaden your topic, especially if it is not truly regional. See Sample Topics. Give yourself plenty of time. Research takes time and sometimes you have to start over if there is not enough information available on your topic. Schedule your time to work on the project especially if working with a partner. Make an outline. Your outline is your strategy. Develop a series of questions relating to the information you need to find. Use these questions to organize and plan your research. It is a good idea to list keywords related to your topic (this will help in catalogue and online searches). Make a list of possible sources of information. Use a variety of sources but try to limit Internet and anecdotal sources. Browse general sources such as encyclopedias and handbooks to gather some background information on your topic. -

Imperial Commerce and the Canadian Muse the Hudson’S Bay Company’S Poetic Advertising Campaign of 1966–1972

Michael Ross and Lorraine York Imperial Commerce and the Canadian Muse The Hudson’s Bay Company’s Poetic Advertising Campaign of 1966–1972 In July of 1965, Barbara Kilvert, the Executive Assistant of Public Relations with the Hudson’s Bay Company, kicked off an unusual advertising campaign by buying a poem from Al Purdy. She had come across a review of Cariboo Horses in the May issue of Time magazine, and, in her words, “decided I should make contact.” As she later reminisced, “This was the beginning of it all.” “It all” referred to a promotional venture inaugurated by Purdy’s “Arctic Rhododendrons”—a series of ads featuring “new poems by Canadian poets, with layout design handled by young artists” (Kilvert, Annotation, Purdy Review). Over the next six years, the advertisements appeared in such respected periodicals as Quarry, The Tamarack Review, Canadian Literature, The Malahat Review, Cité Libre, and Liberté. Participants in the ad campaign made for an impressive roster of writers, including, besides Purdy, Margaret Atwood, Earle Birney, Louis Dudek, Joan Finnegan, Phyllis Gotlieb, Ralph Gustafson, D. G. Jones, Gustave Lamarche, Gwendolyn MacEwen, John Newlove, Alden Nowlan, Michael Ondaatje, Fernand Ouellette, P. K. Page, Jean-Guy Pilon, James Reaney, A. J. M. Smith, Raymond Souster, and Miriam Waddington. Focussing on HBC’s use of original works by Canadian poets in three of these journals—Quarry, Tamarack, and Canadian Literature—(See Appendix), this essay assesses the consequences of recontextualizing poems within a commercial frame of reference. Some of those consequences, as we will argue, were positive. Others, however, were troubling; poetic meaning could irresistibly be drawn into the orbit of HBC’s commercial objectives. -

Gender and the Search for Identity in Gwendolyn Macewan's Julian And

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 1990 Gender and The Search for Identity in Gwendolyn MacEwan’s Julian and Noman Stories Anne Marie Martin Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Anne Marie, "Gender and The Search for Identity in Gwendolyn MacEwan’s Julian and Noman Stories" (1990). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1593. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1593 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gender and The Search for Identity in Gwendolyn MacEwen's Julian and Noman Stories by Anne Marie Martin B.A., York University, 1972 Thesis Submitted to the Department of Religion and Culture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree Wilfrid Laurier University 1990 (S) Anne M. Martin 1990 Property of the Library Wilfrid Laurier University UMI Number: EC56419 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation PuWinhing UMI EC56419 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. -

PRISM International Is a Journal of Contemporary Writing, Published Three Times a Year by the University of British Columbia

international PRISM Summer, ig66 $1.25 STAFF EDITOR-IN CHIEF Jacob Zilber ASSOCIATE EDITORS Robert Harlow Prose Dorothy Livesay Poetry ART EDITOR David Mayrs ADVISORY EDITOR Jan de Bruyn BUSINESS MANAGER Cherie Smith ILLUSTRATIONS COVER PHOTO David Mayrs ESSAY PHOTO Stanley Read PRINTED BY MORRISS PRINTING COMPANY LTD., VICTORIA, B.C. PRISM international is a journal of contemporary writing, published three times a year by the University of British Columbia. Annual subscriptions are $3.50, single copies $1.25, obtainable by writing to PRISM, c/o Creative Writing, U.B.C, Vancouver 8, Canada. MSS should be sent to the Editors at the same address and must be accom panied by a self-addressed envelope and Canadian or unattached U.S. stamps, or commonwealth or international reply coupons. PRISM international VOLUME SIX NUMBER ONE CONTENTS ESSAY Janus ROY DANIELLS 4 A SELECTION OF POETRY FROM OTHER LANGUAGES Two Poems PAULO BOMFIM 12 (with translations from the Portuguese by DORA PETTINELLA) Ferthalag KARI MAROARSON I4 (with translation by the author from his original Icelandic poem) Langst Hat Die Sonne SIMON GRABOWSKI 16 (with translation by the author from his original German poem) Two Poems GWENDOLYN MACEWEN 17 (with translations by the author from her original "Egyptian hieroglyphs") FROM ENGLAND, SCOTLAND, IRELAND A Merry Month KHADAMBI ASALACHE 20 In the Park JEFF NUTTALL 21 Two Poems MICHAEL HOROVITZ 22 Two Poems A. W. TREES 24 Two Poems LENRIE PETERS 27 Two Poems D. M. THOMAS 29 Two Poems SALLY ROBERTS 31 Three Poems KNUTE SKINNER 33 Two Poems L. M. HERRIGKSON 35 2 FROM AUSTRALIA Death of a God GRACE PERRY 36 FROM GERMANY Three Poems GASTON BART-WILLIAMS 36 FROM THE UNITED STATES South of the Sepulchre JAMES EVANS 42 Timber Blue Haze DUANE MCGINNIS 43 Two Poems DENNIS TRUDELL 44 Survivals BARBARA DRAKE 45 Seven Poems J. -

“To Make a Show of Concealing”: the Revision of Satire in Earle Birney's

“To Make a Show of Concealing”: The Revision of Satire in Earle Birney’s “Bushed” Duncan McFarlane long with “David” and “The Damnation of Vancouver,” “Bushed” stands at the head of Earle Birney’s body of poetic work: in popular fame and literary craft, earnestly revered A“with a rather schoolboyish veneration” (Purdy 75) by critics and poets alike. The poem also marks a turning point in Birney’s career. It came just after the completion of his first novel, Turvey, appearing in the col- lection Trial of a City and Other Verse (1952), of which Northrop Frye says “that for virtuosity of language there has never been anything like it in Canadian poetry” (Bush 16), and in which A.J.M. Smith observes “a distinct advance on the simple and unified narrative ‘David’” (12). Yet to look solely at the finished poem is, in this case, to understand a fraction of its total significance. In the process of drafting and revis- ing “Bushed,” Birney transformed the poem from forthright satire into something else entirely. From its first draft — which has never before been analyzed — to its final version, “Bushed” moves between the two extremes that Frye nominates as central themes in Canadian poetry, “one a primarily comic theme of satire and exuberance, the other a pri- marily tragic theme of loneliness and terror” (Bush 168). The published “Bushed” has more in common with Macbeth than with MacFlecknoe, or with satire at all. The revisionary energies at work in Birney’s creative process are driven by an aesthetic bias expressed most clearly in his criticism on Chaucer, through which he expounds a remarkable and condemnatory view of satire as the adolescence of irony. -

Gwendolyn Macewen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso

Document generated on 09/23/2021 11:56 p.m. Studies in Canadian Literature Études en littérature canadienne Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso Resurfacing: Women Writing in 1970s Canada Refaire surface : écrivaines canadiennes des années 1970 Volume 44, Number 2, 2019 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1070963ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1070963ar See table of contents Publisher(s) University of New Brunswick, Dept. of English ISSN 0380-6995 (print) 1718-7850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Eso, D. (2019). Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 44(2), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.7202/1070963ar All Rights Reserved ©, 2020 Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit littérature canadienne (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso When they are the work of poets, entertainments, pranks, and hoaxes still fall within the domain of poetry. — François Le Lionnais, Regent, Collège -

Dalrev Vol67 Iss4 Pp425 435.Pdf (5.693Mb)

Larry McDonald The Politics of Influence: Birney, Scott, Livesay and the Influence of Politics The immediate focus of this essay is the manner in which most criti cism of Dorothy Livesay, Frank Scott and Ear le Birney has worked to obscure the influence of politics on their writing. More specifically (because the actual extent of political influence must be set aside for the moment), my aim is to demonstrate that dominant critical approaches have foreclosed any possibility of political influence on the writing by disguising, diminishing or eliminating the role that politics played in their lives. The narrow question of how these writers have been packaged for general consumption is best appreciated, however, if viewed as representative of the way that criticism has neglected a key aspect of Canadian literary history. I refer to a suppressed tradition of affiliations, remarkable in both range and intensity, between Cana dian writers and socialist ideology. The affiliations between our writers and socialist thought have taken many different forms: some have declared their socialist sympa thies in essays and journalism (Archibald Lampman, Margaret Lau rence, Kenneth Leslie); some worked long and hard for left-wing organizations or political parties (Earle Birney for the Trotskyists, Dorothy Lives ay for the Communists, Frank Scott for the CCF I NDP, David Fennario for the Socialist Labour Party); some stood for politi cal office (F. P. Grove, A. M. Klein, Phyllis Webb, Robin Mathews); some were involved with literary journals that promoted a socialist aesthetic (John Sutherland, Irving Layton, Louis Dudek, Patrick Anderson, Milton Acorn, Al Purdy, Miriam Waddington, Margaret Atwood). -

C19 Singularities.Pdf

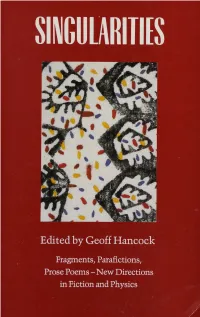

Singularities 1111111111\\ I \\\\II\ 1\1111\ 1\\1 1111111111 11111111111111111111111 3 9345 00923319 2 CLC SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS PR 9073 846 1990 Singularities . Edited by Geoff Hancoclz Singularities: Fragments, Parafictions, Prose Poems - New Directions in Fiction and Physics Black Moss Press <e> Geoff Hancock 1990 Published by Black Moss Press, 1939 Al ace, Windsor, Ontario, Canada NSW lMS. Black Moss Press books are distributed by Firefly Books, 250 Sparks Avenue, Willowdale, Ontario M2H 2S4 Flnancial assistance toward publication was gratefully received from the Canada Council and the Ontario Arts Council. Cover design: Turkish folk artist Printed and bound in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under ti tie: Singularities ISBN 0-88753-203-9 1. Canadian prose literature !English) - 20th century. I. Hancock, Geoff, 1946- PS8329.S46 1990 C818'.540808 C90-090052-0 PR9194.9.S46 1990 I have the universe all to myself. The universe has me all to itself. - Peter Matthiessen, The Snow Leopard Contents ckno' led ement · w urry Th Atomic tructur of Silence 11 av Godfrey from I Ching Kanada 12 v ndolyn MacEwen An Evening with Grey Owl 16 Erin Moure The Origin of Horses 19 J Ro enblatt from Bride of the Stream 19 Michael Dean An Aural History of Lawns 21 ean o huigin from The Nightmare Alphabet 27 nne zumigalski The Question 29 Karl Jirgen Strappado 30 Lola LeMire Tostevin A Weekend at the Semiotics of Eroticism Colloquium Held at Victoria College 33 maro Kambourelli It Was Not A Dark and Stormy Night 34 George McWhirter Nobody's Notebook 36 Michael Bullock Johannes Weltseele Enters the Garden 45 Claire Harris After the Chinese 50 Patrick Lane Ned Coker's Dream 54 Gay Allison The Slow Gathering Of 60 Eugene McNamara Falling in Place 64 hp Nichol The Toes 69 Rod Willmot from The Ribs of Dragonfl_y 71 Paul Dutton Uncle Rebus Clean Song 73 Fred W ab Elite 78 Daphne Marlatt&.