Nordlit 35, 2015 TERROR and EREBUS by GWENDOLYN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aglooka Advisor Spring 2019

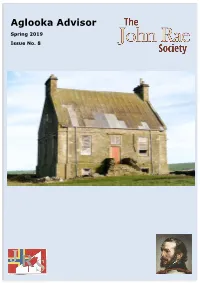

Aglooka Advisor Spring 2019 Issue No. 8 Aglooka Advisor Spring 2019 Issue No.8 President’s Report page 4 Eric Marwick: an obituary page 6 Polar Exploration: article by John Ramwell page 7 Dr John Rae Commemorated on an Unusual Scale: links to an article by Rognvald Boyd on the JRS website page 8 Two Art Exhibitions: article by Sigrid Appleby page 9 RICS honours John Rae: report by Fiona Gould page 10 Hall of Clestrain: archaeological report by Dan Lee page 10 Memories of Two Canadians: article by Anne Clark page 11 An Unexpected Guest: newspaper report from 1858 submitted by Fiona Sutherland page 12 Take the Torch: book review page 13 Arctic Return Expedition: update by David Reid page 14 Poster Competition: results page 15 Notices page 16 Photo on front cover by John Welburn, ABIPP, showing roof patches, new guttering and heavy-duty plastic covering on windows. - 2 - Patrons Dr Peter St John, The Earl of Orkney Ken McGoogan, Author Ray Mears, Author & TV Presenter Bill Spence, Lord Lieutenant of Orkney Sir Michael Palin Magnus Linklater CBE Board of Trustees (in alphabetical order by surname) Andrew Appleby — Jim Chalmers — Anna Elmy — Neil Kermode — Fiona Lettice Mark Newton — Norman Shearer Committee President — Andrew Appleby Chairman — Norman Shearer Honorary Secretary — Anna Elmy Honorary Treasurer — Fiona Lettice Webmaster and Social Media — Mark Newton Membership Secretary — Fiona Gould Administrative Secretary — Julie Cassidy Registered Office The John Rae Society 7 Church Road Stromness Orkney KW16 3BA Tel: 01856 851414 e-mail: [email protected] Newsletter Editor — Fiona Gould The views expressed in this newsletter are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editor or the Board of Trustees of the John Rae Society. -

MS Coll 00121

MS. MACEWEN, GWENDOLYN COLL. PAPERS, 1955-1988 121 CHRONOLOGY 1941 Born in Toronto, daughter of Elsie Doris Mitchell and Alick James McEwen. 1948 Published first poem in The Canadian Forum 1955-1959 Attended Western Technical High School 1959 Left school to be a writer: wrote plays and dramatic documentaries for CBC radio which are mainly unpublished, and poetry and fiction. 1959-63 Worked in children’s library Issued Saturnalia, poem, broadside, lithograph. 1961 Published privately Selah and The Drunken Clock, both limited to 100 copies and both books (pamphlets) of poetry 1962 Married and separated from Milton Acorn 1963 Published Julian the Magician, a novel, and The Rising Fire, poems 1965 Received CBC New Canadian Writing contest 1966 Published A Breakfast for Barbarians, poems 1969 Published The Shadow-maker, poems, which won the Governor General’s Award 1970? Published Jewelry: a Poem, a broadside 1971 Published King of Egypt, King of Dreams, a novel Married Nikos Tsingos 1972 Operated the Trojan Horse, a coffee house in Toronto with Nikos Tsingos, a Greek singer to whom she was married for six years Published Noman, a collection of short stories (reprinted 1985) 1 MS. MACEWEN, GWENDOLYN COLL. PAPERS, 1955-1988 121 CHRONOLOGY 1973 Published The Armies of the Moon, poems Received A.J.M. Smith Award 1974 Magic Animals, poems (reprinted 1984) 1976 Published The Fire Eaters, poems 1978 Published Mermaids and Ikons; a Greek Summer, travel recollections of Greece 1979 Published The Trojan Women; a play 1980 Published The Man with three Violins, broadside 1981 Published The Chocolate Moose, a children’s book Published The Trojan Women which contains her version of Euripides’ The Trojan Women and her translation of two poems, “Helen” and “Orestes” by Yannis Ritsos 1982 Published The T.E. -

På Isen Amundsen Af Niels Aage Jensen – 99.4 – Jubilæumsliste 2011

Kuldegys på isen Amundsen af Niels Aage Jensen – 99.4 – jubilæumsliste 2011. 334 sider En bog om Roald Amundsens liv som opdagelsesrejsende og polarforsker. For 100 år siden – om eftermiddagen den 14. december 1911 - lykkedes Hans skibsekspeditioner og forsøg med transpolare flyvninger beskrives, det Roald Amundsen at blive det første menneske i verden, som nåede ligesom hans sammensatte personlighed skildres. frem til Sydpolen. Han vandt kapløbet foran Robert Scott, der kom en måned for sent og omkom på hjemvejen. Den fremmede fortryller - beretning om Knud Rasmussen og hans to folk Tag en rejse tilbage i tiden til de store polarforskere, der har skrevet sig ind af Ebbe Kløvedal Reich – 99.4 i historien ved deres ufattelige bedrifter på isen både i syd og nord: norske 1995. 296 sider Roald Amundsen, britiske Robert Scott, danske Knud Rasmussen m.fl. Et portræt af grønlandsfareren og privatpersonen Knud Rasmussen, der, som forfatteren skriver i forordet, er tegnet på afstand og med frihånd: Jeg har udvalgt en række biografier om polarforskerne og deres ekspe- ”Jeg har opsøgt den tilgængelige viden, men en del af den har jeg udeladt”. ditioner og fundet bøger og film om is, sne og kulde, klimaforhold og Ønsker du at læse om Knud Rasmussens eventyrlige liv og gerninger, hvor klimaforandringer i polarområderne og på Grønland. Til sidst er en liste vægten er på den gode historie, er denne biografi et godt bud. over relevante hjemmesider. Den sidste dagbog Så er du til kolde gys og facts, så rigtig god fornøjelse. af Rober Falcon Scott – 99.4 2009. 473 sider De fulde dagbogsoptegnelser fra Robert F. -

Knud Rasmussen Glacier Status Analysis Based on Historical Data and Moving Detection Using RPAS

applied sciences ArticleArticle KnudKnud RasmussenRasmussen GlacierGlacier StatusStatus AnalysisAnalysis BasedBased onon HistoricalHistorical DataData andand MovingMoving DetectionDetection UsingUsing RPASRPAS KarelKarel PavelkaPavelka **, Jaroslav, Jaroslav Šedina Šedina and and Karel Karel Pavelka Pavelka,, Jr Jr.. FacultyFaculty ofof CivilCivil Engineering,Engineering, CzechCzech TechnicalTechnical University University in in Prague, Prague, Thakurova Thakurova 7, 7, 16629 16629 Prague, Prague Czech, Republic; [email protected] Republic; [email protected] (J.Š.); [email protected] (J.Š.) [email protected] (K.P.J.) (K.P.J.) ** Correspondence:Correspondence: [email protected]; [email protected]; Tel.: Tel.: +420-608-211-360 +420-608-211-360 Abstract:Abstract: ThisThis articlearticle discussesdiscusses partialpartial resultsresults ofof anan internationalinternational scientificscientific expeditionexpedition toto GreenlandGreenland thatthat researchedresearched thethe geography,geography, geodesy,geodesy, botany,botany, andand glaciologyglaciology ofof thethe area.area. TheThe resultsresults herehere focusfocus onon the photogrammetrical results results obtained obtained with with the the eBee eBee drone drone in in the the eastern eastern part part ofof Greenland Greenland at atthe the front front of ofthe the Knud Knud Rasmussen Rasmussen Glacier Glacier and and the theuse useof archive of archive image image data data for monitoring for monitoring the con- the conditiondition of this of thisglacier glacier.. In these In theseshort- short-termterm visits to visits the site, to the the site, possibility the possibility of using ofa drone using is a discussed drone is discussedand the results and the show results not showonly the not flow only thespeed flow of speedthe glacier of the but glacier alsobut the alsoshape the and shape structure and structure from a fromheight a heightof up to of 200 up m. -

Imperial Commerce and the Canadian Muse the Hudson’S Bay Company’S Poetic Advertising Campaign of 1966–1972

Michael Ross and Lorraine York Imperial Commerce and the Canadian Muse The Hudson’s Bay Company’s Poetic Advertising Campaign of 1966–1972 In July of 1965, Barbara Kilvert, the Executive Assistant of Public Relations with the Hudson’s Bay Company, kicked off an unusual advertising campaign by buying a poem from Al Purdy. She had come across a review of Cariboo Horses in the May issue of Time magazine, and, in her words, “decided I should make contact.” As she later reminisced, “This was the beginning of it all.” “It all” referred to a promotional venture inaugurated by Purdy’s “Arctic Rhododendrons”—a series of ads featuring “new poems by Canadian poets, with layout design handled by young artists” (Kilvert, Annotation, Purdy Review). Over the next six years, the advertisements appeared in such respected periodicals as Quarry, The Tamarack Review, Canadian Literature, The Malahat Review, Cité Libre, and Liberté. Participants in the ad campaign made for an impressive roster of writers, including, besides Purdy, Margaret Atwood, Earle Birney, Louis Dudek, Joan Finnegan, Phyllis Gotlieb, Ralph Gustafson, D. G. Jones, Gustave Lamarche, Gwendolyn MacEwen, John Newlove, Alden Nowlan, Michael Ondaatje, Fernand Ouellette, P. K. Page, Jean-Guy Pilon, James Reaney, A. J. M. Smith, Raymond Souster, and Miriam Waddington. Focussing on HBC’s use of original works by Canadian poets in three of these journals—Quarry, Tamarack, and Canadian Literature—(See Appendix), this essay assesses the consequences of recontextualizing poems within a commercial frame of reference. Some of those consequences, as we will argue, were positive. Others, however, were troubling; poetic meaning could irresistibly be drawn into the orbit of HBC’s commercial objectives. -

Gender and the Search for Identity in Gwendolyn Macewan's Julian And

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 1990 Gender and The Search for Identity in Gwendolyn MacEwan’s Julian and Noman Stories Anne Marie Martin Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Anne Marie, "Gender and The Search for Identity in Gwendolyn MacEwan’s Julian and Noman Stories" (1990). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1593. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1593 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gender and The Search for Identity in Gwendolyn MacEwen's Julian and Noman Stories by Anne Marie Martin B.A., York University, 1972 Thesis Submitted to the Department of Religion and Culture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree Wilfrid Laurier University 1990 (S) Anne M. Martin 1990 Property of the Library Wilfrid Laurier University UMI Number: EC56419 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation PuWinhing UMI EC56419 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. -

MÆRSK Skælskør

* On August 1, 1972, the first Danish oil was brought ashore at Stigsnæs near MÆRSK Skælskør. It came from the Dan Field, 200 kilometres west of Esbjerg. That signalled the beginning of a new era and I expressed the hope that this new development would benefit the entire Danish society, that Danish oil production would prove a valuable contribution to the development of trade and industry in our country, and that, in the long run, Denmark would become self-sufficient, up to a point at least, in terms of the most important source of energy at that time. Published by A.P. Møller, Copenhagen Editor: Einar Siberg Now, 15 years later, I am happy to say that these hopes have essentially Printers: scanprint, Jyllands-Posten A/s, come true. But not without effort. Viby J The original Dan Field - platforms A, B & C - turned out to be a dis- Local correspondents: appointment. The experts had forecast a yearly production of 500,000 tons from the five wells; but the limestone in the reservoir was stubborn and HONG KONG: Lars Christiansen production in the first year 1972 totalled just 93,000 tons and in the second INDONESIA: Lars R. Jacobsen year 134,000 tons. But progress has been made. In 1976 the Dan Field was JAPAN: M. Konishi extended with a D platform, in 1977 with an E platform and in 1987 with the PHILIPPINES: Lydia B. Cervantes F platform. Other fields have been established - the oil fields Gorm (1981), SINGAPORE: David Tan Skjold (1982), and Rolf (1986), and in 1984 the Tyra gas field - bringing the THAILAND: Pornchai Vimolratana estimate for combined oil and gas production to the equivalent of 7 million UNITED KINGDOM: Ann Thornton tons of oil or about 65% of Denmark's consumption of oil and gas. -

Ideas, 11 | Printemps/Été 2018 Opera in the Arctic: Knud Rasmussen, Inside and Outside Modernity 2

IdeAs Idées d'Amériques 11 | Printemps/Été 2018 Modernités dans les Amériques : des avant-gardes à aujourd’hui Opera in the Arctic: Knud Rasmussen, Inside and Outside Modernity L’Opéra dans l’Arctique : Knud Rasmussen, traversées de la modernité Ópera en el Árctico: Knud Rasmussen, travesías de la modernidad Smaro Kamboureli Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2553 DOI: 10.4000/ideas.2553 ISSN: 1950-5701 Publisher Institut des Amériques Electronic reference Smaro Kamboureli, « Opera in the Arctic: Knud Rasmussen, Inside and Outside Modernity », IdeAs [Online], 11 | Printemps/Été 2018, Online since 18 June 2018, connection on 21 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2553 ; DOI : 10.4000/ideas.2553 This text was automatically generated on 21 April 2019. IdeAs – Idées d’Amériques est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Opera in the Arctic: Knud Rasmussen, Inside and Outside Modernity 1 Opera in the Arctic: Knud Rasmussen, Inside and Outside Modernity L’Opéra dans l’Arctique : Knud Rasmussen, traversées de la modernité Ópera en el Árctico: Knud Rasmussen, travesías de la modernidad Smaro Kamboureli I. Early 1920s: under western eyes 1 When Greenlander / Danish ethnographer Knud Rasmussen approached a small Padlermiut camp in what is today the Kivalliq Region of Nunavut, Canada, he was surprised to hear “a powerful gramophone struck up, and Caruso’s mighty voice [ringing] out from his tent” (Rasmussen, K., 1927: 63). It was 1922, and the Inuktitut-speaking Rasmussen was after traditional Inuit knowledge, specifically spiritual and cultural practices. -

(Post) Colonial Relations on Display Contemporary Trends in Museums and Art Exhibitions Depicting Greenland

Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education (Post) Colonial Relations on Display Contemporary Trends in Museums and Art Exhibitions depicting Greenland Vanessa Brune Thesis submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies May 2016 (Post) Colonial Relations on Display Contemporary Trends in Museums and Art Exhibitions depicting Greenland A Thesis submitted by: Vanessa Brune Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education UiT - The Arctic University of Norway Spring 2016 Cover Page: Statue of Hans Egede, a Danish pastor who introduced the Christian mission and thereby colonisation to Greenland, overlooking the colonial harbour of Nuuk. Picture taken by Vanessa Brune. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank everyone I had the pleasure to meet and/or conduct interviews with during my fieldwork in Copenhagen and Nuuk. This thesis would not have been possible without all your valuable help, insight, information and recommendations and I am so grateful that you took the time to answer my questions. In particular I want to thank: MARTI and the Greenlandic House in Copenhagen The National Museum of Denmark The North Atlantic House in Copenhagen The Photographic Centre in Copenhagen The National Museum of Greenland Nuuk Art Museum The Project “Inuit Now” Secondly, I would like to thank my supervisor Bjørn Ola Tafjord for always being supportive, for taking so much time to help and guide me, and of course for constantly pushing me to go the extra mile. I know it was worth it. Also, thanks to the Centre of Sami Studies for the chance to conduct this study and for providing me with the opportunity to do research in Greenland. -

PRISM International Is a Journal of Contemporary Writing, Published Three Times a Year by the University of British Columbia

international PRISM Summer, ig66 $1.25 STAFF EDITOR-IN CHIEF Jacob Zilber ASSOCIATE EDITORS Robert Harlow Prose Dorothy Livesay Poetry ART EDITOR David Mayrs ADVISORY EDITOR Jan de Bruyn BUSINESS MANAGER Cherie Smith ILLUSTRATIONS COVER PHOTO David Mayrs ESSAY PHOTO Stanley Read PRINTED BY MORRISS PRINTING COMPANY LTD., VICTORIA, B.C. PRISM international is a journal of contemporary writing, published three times a year by the University of British Columbia. Annual subscriptions are $3.50, single copies $1.25, obtainable by writing to PRISM, c/o Creative Writing, U.B.C, Vancouver 8, Canada. MSS should be sent to the Editors at the same address and must be accom panied by a self-addressed envelope and Canadian or unattached U.S. stamps, or commonwealth or international reply coupons. PRISM international VOLUME SIX NUMBER ONE CONTENTS ESSAY Janus ROY DANIELLS 4 A SELECTION OF POETRY FROM OTHER LANGUAGES Two Poems PAULO BOMFIM 12 (with translations from the Portuguese by DORA PETTINELLA) Ferthalag KARI MAROARSON I4 (with translation by the author from his original Icelandic poem) Langst Hat Die Sonne SIMON GRABOWSKI 16 (with translation by the author from his original German poem) Two Poems GWENDOLYN MACEWEN 17 (with translations by the author from her original "Egyptian hieroglyphs") FROM ENGLAND, SCOTLAND, IRELAND A Merry Month KHADAMBI ASALACHE 20 In the Park JEFF NUTTALL 21 Two Poems MICHAEL HOROVITZ 22 Two Poems A. W. TREES 24 Two Poems LENRIE PETERS 27 Two Poems D. M. THOMAS 29 Two Poems SALLY ROBERTS 31 Three Poems KNUTE SKINNER 33 Two Poems L. M. HERRIGKSON 35 2 FROM AUSTRALIA Death of a God GRACE PERRY 36 FROM GERMANY Three Poems GASTON BART-WILLIAMS 36 FROM THE UNITED STATES South of the Sepulchre JAMES EVANS 42 Timber Blue Haze DUANE MCGINNIS 43 Two Poems DENNIS TRUDELL 44 Survivals BARBARA DRAKE 45 Seven Poems J. -

Gwendolyn Macewen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso

Document generated on 09/23/2021 11:56 p.m. Studies in Canadian Literature Études en littérature canadienne Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso Resurfacing: Women Writing in 1970s Canada Refaire surface : écrivaines canadiennes des années 1970 Volume 44, Number 2, 2019 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1070963ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1070963ar See table of contents Publisher(s) University of New Brunswick, Dept. of English ISSN 0380-6995 (print) 1718-7850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Eso, D. (2019). Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 44(2), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.7202/1070963ar All Rights Reserved ©, 2020 Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit littérature canadienne (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Perfect Mismatch: Gwendolyn MacEwen and the Flat Earth Society David Eso When they are the work of poets, entertainments, pranks, and hoaxes still fall within the domain of poetry. — François Le Lionnais, Regent, Collège -

Who's Afraid of Kaassassuk? Writing As a Tool in Coping with Changing

Document generated on 09/30/2021 3:42 p.m. Études/Inuit/Studies Who’s afraid of Kaassassuk? Writing as a tool in coping with changing cosmology Qui a peur de Kaassassuk? L’écriture comme outil pour faire face à une cosmologie changeante Birgitte Sonne Technologies créatives Article abstract Creative technologies Education, literacy, and art were technologies used by Greenlanders in Volume 34, Number 2, 2010 adapting to and coping with changes brought about by colonial impacts from Denmark. Stories orally transmitted through the ages were among the first URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1004072ar texts to be written by Greenlanders. This article focuses on changes in symbolic DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1004072ar meanings of the environmental setting in the pan-Inuit myth about the maltreated orphan Kaassassuk who became a strong man and took a terrible revenge. Beginning with the traditional pan-Inuit and Greenland variants, the See table of contents analysis ends up with Hans Lynge’s play Kâgssagssuk, staged in 1966. Traditionally, the symbolism of the natural forces underscored Kaassassuk’s brutal character, but later it structured the literary composition of his story Publisher(s) and changed him into a re-socialised individual. In Lynge’s play, the natural forces even gave way to contemporary moral and psychological considerations Association Inuksiutiit Katimajiit Inc. during the political upheaval leading to Greenland’s Home Rule. Centre interuniversitaire d’études et de recherches autochtones (CIÉRA) ISSN 0701-1008 (print) 1708-5268 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Sonne, B. (2010). Who’s afraid of Kaassassuk? Writing as a tool in coping with changing cosmology.