Who's Afraid of Kaassassuk? Writing As a Tool in Coping with Changing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aglooka Advisor Spring 2019

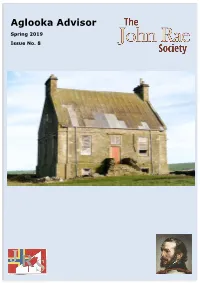

Aglooka Advisor Spring 2019 Issue No. 8 Aglooka Advisor Spring 2019 Issue No.8 President’s Report page 4 Eric Marwick: an obituary page 6 Polar Exploration: article by John Ramwell page 7 Dr John Rae Commemorated on an Unusual Scale: links to an article by Rognvald Boyd on the JRS website page 8 Two Art Exhibitions: article by Sigrid Appleby page 9 RICS honours John Rae: report by Fiona Gould page 10 Hall of Clestrain: archaeological report by Dan Lee page 10 Memories of Two Canadians: article by Anne Clark page 11 An Unexpected Guest: newspaper report from 1858 submitted by Fiona Sutherland page 12 Take the Torch: book review page 13 Arctic Return Expedition: update by David Reid page 14 Poster Competition: results page 15 Notices page 16 Photo on front cover by John Welburn, ABIPP, showing roof patches, new guttering and heavy-duty plastic covering on windows. - 2 - Patrons Dr Peter St John, The Earl of Orkney Ken McGoogan, Author Ray Mears, Author & TV Presenter Bill Spence, Lord Lieutenant of Orkney Sir Michael Palin Magnus Linklater CBE Board of Trustees (in alphabetical order by surname) Andrew Appleby — Jim Chalmers — Anna Elmy — Neil Kermode — Fiona Lettice Mark Newton — Norman Shearer Committee President — Andrew Appleby Chairman — Norman Shearer Honorary Secretary — Anna Elmy Honorary Treasurer — Fiona Lettice Webmaster and Social Media — Mark Newton Membership Secretary — Fiona Gould Administrative Secretary — Julie Cassidy Registered Office The John Rae Society 7 Church Road Stromness Orkney KW16 3BA Tel: 01856 851414 e-mail: [email protected] Newsletter Editor — Fiona Gould The views expressed in this newsletter are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editor or the Board of Trustees of the John Rae Society. -

På Isen Amundsen Af Niels Aage Jensen – 99.4 – Jubilæumsliste 2011

Kuldegys på isen Amundsen af Niels Aage Jensen – 99.4 – jubilæumsliste 2011. 334 sider En bog om Roald Amundsens liv som opdagelsesrejsende og polarforsker. For 100 år siden – om eftermiddagen den 14. december 1911 - lykkedes Hans skibsekspeditioner og forsøg med transpolare flyvninger beskrives, det Roald Amundsen at blive det første menneske i verden, som nåede ligesom hans sammensatte personlighed skildres. frem til Sydpolen. Han vandt kapløbet foran Robert Scott, der kom en måned for sent og omkom på hjemvejen. Den fremmede fortryller - beretning om Knud Rasmussen og hans to folk Tag en rejse tilbage i tiden til de store polarforskere, der har skrevet sig ind af Ebbe Kløvedal Reich – 99.4 i historien ved deres ufattelige bedrifter på isen både i syd og nord: norske 1995. 296 sider Roald Amundsen, britiske Robert Scott, danske Knud Rasmussen m.fl. Et portræt af grønlandsfareren og privatpersonen Knud Rasmussen, der, som forfatteren skriver i forordet, er tegnet på afstand og med frihånd: Jeg har udvalgt en række biografier om polarforskerne og deres ekspe- ”Jeg har opsøgt den tilgængelige viden, men en del af den har jeg udeladt”. ditioner og fundet bøger og film om is, sne og kulde, klimaforhold og Ønsker du at læse om Knud Rasmussens eventyrlige liv og gerninger, hvor klimaforandringer i polarområderne og på Grønland. Til sidst er en liste vægten er på den gode historie, er denne biografi et godt bud. over relevante hjemmesider. Den sidste dagbog Så er du til kolde gys og facts, så rigtig god fornøjelse. af Rober Falcon Scott – 99.4 2009. 473 sider De fulde dagbogsoptegnelser fra Robert F. -

Knud Rasmussen Glacier Status Analysis Based on Historical Data and Moving Detection Using RPAS

applied sciences ArticleArticle KnudKnud RasmussenRasmussen GlacierGlacier StatusStatus AnalysisAnalysis BasedBased onon HistoricalHistorical DataData andand MovingMoving DetectionDetection UsingUsing RPASRPAS KarelKarel PavelkaPavelka **, Jaroslav, Jaroslav Šedina Šedina and and Karel Karel Pavelka Pavelka,, Jr Jr.. FacultyFaculty ofof CivilCivil Engineering,Engineering, CzechCzech TechnicalTechnical University University in in Prague, Prague, Thakurova Thakurova 7, 7, 16629 16629 Prague, Prague Czech, Republic; [email protected] Republic; [email protected] (J.Š.); [email protected] (J.Š.) [email protected] (K.P.J.) (K.P.J.) ** Correspondence:Correspondence: [email protected]; [email protected]; Tel.: Tel.: +420-608-211-360 +420-608-211-360 Abstract:Abstract: ThisThis articlearticle discussesdiscusses partialpartial resultsresults ofof anan internationalinternational scientificscientific expeditionexpedition toto GreenlandGreenland thatthat researchedresearched thethe geography,geography, geodesy,geodesy, botany,botany, andand glaciologyglaciology ofof thethe area.area. TheThe resultsresults herehere focusfocus onon the photogrammetrical results results obtained obtained with with the the eBee eBee drone drone in in the the eastern eastern part part ofof Greenland Greenland at atthe the front front of ofthe the Knud Knud Rasmussen Rasmussen Glacier Glacier and and the theuse useof archive of archive image image data data for monitoring for monitoring the con- the conditiondition of this of thisglacier glacier.. In these In theseshort- short-termterm visits to visits the site, to the the site, possibility the possibility of using ofa drone using is a discussed drone is discussedand the results and the show results not showonly the not flow only thespeed flow of speedthe glacier of the but glacier alsobut the alsoshape the and shape structure and structure from a fromheight a heightof up to of 200 up m. -

MÆRSK Skælskør

* On August 1, 1972, the first Danish oil was brought ashore at Stigsnæs near MÆRSK Skælskør. It came from the Dan Field, 200 kilometres west of Esbjerg. That signalled the beginning of a new era and I expressed the hope that this new development would benefit the entire Danish society, that Danish oil production would prove a valuable contribution to the development of trade and industry in our country, and that, in the long run, Denmark would become self-sufficient, up to a point at least, in terms of the most important source of energy at that time. Published by A.P. Møller, Copenhagen Editor: Einar Siberg Now, 15 years later, I am happy to say that these hopes have essentially Printers: scanprint, Jyllands-Posten A/s, come true. But not without effort. Viby J The original Dan Field - platforms A, B & C - turned out to be a dis- Local correspondents: appointment. The experts had forecast a yearly production of 500,000 tons from the five wells; but the limestone in the reservoir was stubborn and HONG KONG: Lars Christiansen production in the first year 1972 totalled just 93,000 tons and in the second INDONESIA: Lars R. Jacobsen year 134,000 tons. But progress has been made. In 1976 the Dan Field was JAPAN: M. Konishi extended with a D platform, in 1977 with an E platform and in 1987 with the PHILIPPINES: Lydia B. Cervantes F platform. Other fields have been established - the oil fields Gorm (1981), SINGAPORE: David Tan Skjold (1982), and Rolf (1986), and in 1984 the Tyra gas field - bringing the THAILAND: Pornchai Vimolratana estimate for combined oil and gas production to the equivalent of 7 million UNITED KINGDOM: Ann Thornton tons of oil or about 65% of Denmark's consumption of oil and gas. -

Ideas, 11 | Printemps/Été 2018 Opera in the Arctic: Knud Rasmussen, Inside and Outside Modernity 2

IdeAs Idées d'Amériques 11 | Printemps/Été 2018 Modernités dans les Amériques : des avant-gardes à aujourd’hui Opera in the Arctic: Knud Rasmussen, Inside and Outside Modernity L’Opéra dans l’Arctique : Knud Rasmussen, traversées de la modernité Ópera en el Árctico: Knud Rasmussen, travesías de la modernidad Smaro Kamboureli Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2553 DOI: 10.4000/ideas.2553 ISSN: 1950-5701 Publisher Institut des Amériques Electronic reference Smaro Kamboureli, « Opera in the Arctic: Knud Rasmussen, Inside and Outside Modernity », IdeAs [Online], 11 | Printemps/Été 2018, Online since 18 June 2018, connection on 21 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2553 ; DOI : 10.4000/ideas.2553 This text was automatically generated on 21 April 2019. IdeAs – Idées d’Amériques est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Opera in the Arctic: Knud Rasmussen, Inside and Outside Modernity 1 Opera in the Arctic: Knud Rasmussen, Inside and Outside Modernity L’Opéra dans l’Arctique : Knud Rasmussen, traversées de la modernité Ópera en el Árctico: Knud Rasmussen, travesías de la modernidad Smaro Kamboureli I. Early 1920s: under western eyes 1 When Greenlander / Danish ethnographer Knud Rasmussen approached a small Padlermiut camp in what is today the Kivalliq Region of Nunavut, Canada, he was surprised to hear “a powerful gramophone struck up, and Caruso’s mighty voice [ringing] out from his tent” (Rasmussen, K., 1927: 63). It was 1922, and the Inuktitut-speaking Rasmussen was after traditional Inuit knowledge, specifically spiritual and cultural practices. -

(Post) Colonial Relations on Display Contemporary Trends in Museums and Art Exhibitions Depicting Greenland

Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education (Post) Colonial Relations on Display Contemporary Trends in Museums and Art Exhibitions depicting Greenland Vanessa Brune Thesis submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies May 2016 (Post) Colonial Relations on Display Contemporary Trends in Museums and Art Exhibitions depicting Greenland A Thesis submitted by: Vanessa Brune Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education UiT - The Arctic University of Norway Spring 2016 Cover Page: Statue of Hans Egede, a Danish pastor who introduced the Christian mission and thereby colonisation to Greenland, overlooking the colonial harbour of Nuuk. Picture taken by Vanessa Brune. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank everyone I had the pleasure to meet and/or conduct interviews with during my fieldwork in Copenhagen and Nuuk. This thesis would not have been possible without all your valuable help, insight, information and recommendations and I am so grateful that you took the time to answer my questions. In particular I want to thank: MARTI and the Greenlandic House in Copenhagen The National Museum of Denmark The North Atlantic House in Copenhagen The Photographic Centre in Copenhagen The National Museum of Greenland Nuuk Art Museum The Project “Inuit Now” Secondly, I would like to thank my supervisor Bjørn Ola Tafjord for always being supportive, for taking so much time to help and guide me, and of course for constantly pushing me to go the extra mile. I know it was worth it. Also, thanks to the Centre of Sami Studies for the chance to conduct this study and for providing me with the opportunity to do research in Greenland. -

ROLF Gilbergl Numerous Place Names in Greenland Are Beset With

Thule ROLF GILBERGl Numerous place names in Greenland are beset with some confusion, and Thule is possibly the most nonspecific of them all. An attempt has been made in the following paper, therefore, to set out some of the various meanings which have been attached to the word. ULTIMATHULE In times of antiquity, “Thule” was the name given to an archipelago far to the north of the Scandinavian seas.The Greek explorer Pytheas told his contemporaries about this far-awayplace, and about the year 330 B.C.he sailed northward from Marseilles in France in search of the source of amber. When he reached Britain, heheard of an archipelagofurther north known as “Thule”.The name was apparently Celtic;the archipelago what are now known as the Shetland Isles. AfterPytheas’ time, the ancientscalled Scandinavia “Thule”. In poetry,it became“Ultima Thule”, i.e. “farthest Thule”, a distantnorthern place, geo- ‘ graphically undefined and shrouded in esoteric mystery. As the frontiers of man’s exploration gradually expanded, the legendary Ultima Thule acquired a more northerly location. It moved with the Vikings from the Faroe Islands to Iceland, and, when Iceland was colonized in the ninth century A.D., Greenland became “Thule” in folklore. THULESTATION Perhap Knud Rasmussen had these historical facts in mind when he founded a trading post in 1910 among the Polar Eskimos and called the store “Thule Station”. The committee managing Rasmussen’s station was, incidentally, always referred to as the Cape York Committee, and the official name of the station was “Cape York Station, Thule”. Behind the pyramid-shaped base of the rock called Mount Dundas by British explorers, but generally known as Thule Mountain, on North Star Bay, the best natural harbour in the area, the Polar Eskimos hadplaced their settlement, Umanaq (meaning heart-shaped). -

Lecture 4-06 Slides H A&S 222A

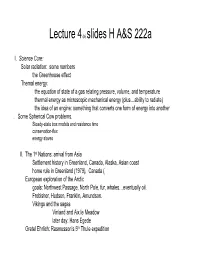

Lecture 4-06 slides H A&S 222a I. Science Core: Solar radiation: some numbers the Greenhouse effect Themal energy: the equation of state of a gas relating pressure, volume, and temperature thermal energy as microscopic mechanical energy (plus…ability to radiate) the idea of an engine: something that converts one form of energy into another . Some Spherical Cow problems. Steady-state box models and residence time conservation-flux energy slaves II. The 1st Nations: arrival from Asia Settlement history in Greenland, Canada, Alaska, Asian coast home rule in Greenland (1979), Canada ( European exploration of the Arctic goals: Northwest Passage, North Pole, fur, whales…eventually oil. Frobisher, Hudson, Franklin, Amundson. Vikings and the sagas Vinland and Aix le Meadow later day: Hans Egede Gretel Ehrlich: Rasmusson’s 5th Thule expedition This is an image from an airplne of cold Arctic winds blowing over ice, then open ocean water. The air erupts in turbulent cloud, feeling the warmth and moisture of the ocean water. This cools the ocean and warms the atmosphere. This kind of heat transport from sea to air is a prime source of circulation of both atmosphere and ocean (although the tropics provide a huge amount of heating of the atmosphere in addition). today’s weather in west Greenland • Observed At:Ilulissat, GL • Elevation:102 ft / 31 m • 25 °F / -4 °C • Mostly CloudyHumidity:50% • Dew Point:9 °F / -13 °C • Wind:4 mph / 6 km/h from the NW • • Pressure:29.65 in / 1004 hPa • Windchill:20 °F / -6 °C Visibility:6.2 miles / • 10.0 kilometers UV:2 out of 16 • Clouds:Few 12000 ft / 3657 m Mostly Cloudy 18000 ft / 5486 m • (Above Ground Level) John Shelden in 1639 told of his discovery of the North Pole, supposedly made of iron, sticking several hundred feet up and surrounded by a ring of ice. -

Newsletternational Museum of Natural History December 2005 Number 13

Smithsonian Institution NewsletterNational Museum of Natural History December 2005www.mnh.si.edu/arctic Number 13 NOTES FROM THE DIRECTOR collaboration between NMNH, NOAA, NASA, and NSF, explores By Bill Fitzhugh arctic environmental change as it effects land, sea, and atmosphere and how these changes impact human populations in the arctic A whirlwind of activities during the past year, including and beyond. When we began planning the exhibit as a public Greenland and Alaska Native Festivals at the Smithsonian, IPY-4 educational outreach component of the SEARCH program (Study planning, new research and publication projects, and a growing of Environmental Arctic Change) sponsored by the Interagency consensus that a major regime change is taking place in arctic Arctic Research Policy Committee three years ago, we had no climate – that ‘Friend Acting Strangely’ as northern Natives have idea this topic would become such a prominent public policy expressed it – have all brought the past year to a close. This time issue. We are therefore looking forward to the Smithsonian taking we are trying to reach you early in the new year, something we part in educating the public about what is certain to be one of the haven’t done for ten years. I also note, with relief, that my stint as most important environmental issues of the coming century. Anthropology Chairman ended in April with the appointment of As these developments in the wider world have been Daniel Rogers to this unfolding, the museum and the position for a five-year term. Smithsonian have been Arctic change is certainly engaged in an extensive period the key-word for this issue, of introspection and renewal for with the past year we seem following several years of to have crossed a threshold in strategic planning and scientific and public budgetary ‘restraint’. -

High Arctic Sovereignty Revisited

ARCTIC VOL. 56, NO. 1 (MARCH 2003) P. 101–109 InfoNorth The Muskox Patrol: High Arctic Sovereignty Revisited by Peter Schledermann HE ROLE OF THE ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE Under Sverdrup’s hugely successful leadership, mem- (RCMP) in the Canadian government’s quest to bers of the Norwegian expedition spent four years map- T secure international recognition of its claims to ping and surveying large, often unknown portions of the sovereignty over the High Arctic islands is a chapter of High Arctic islands. The only people they encountered Canadian history rarely visited. Yet the sovereignty battle were North Greenlandic Inughuit who had crossed Smith over a group of Arctic islands few can even name was the Sound to assist the American explorer Robert Peary in his stuff of high-stakes political poker: bluff indifference mixed quest to reach the North Pole. When the expedition re- with sudden bursts of national interest, courage, hardships, turned to Norway in 1902, Sverdrup began what would and dedication of a high order. Canadian government become a lifelong, personal struggle to press his govern- activities in the High Arctic between 1900 and 1933 were ment into pursuing the claim he had set in motion. While carried out almost exclusively in response to the real or the Norwegian government expressed little official inter- perceived intentions of other nations to challenge Canada’s est in the matter, the Dominion of Canada government sovereignty claims. This story is currently being presented took the claim far more seriously. For centuries, American as a proposal for a documentary film, “The Muskox Pa- and European whalers and explorers had frequented Arctic trol,” by Ole Gjerstad and Peter Schledermann. -

Greenlandic Attitudes Towards Norwegians and Danes

Document generated on 10/01/2021 2:49 p.m. Études/Inuit/Studies Greenlandic attitudes towards Norwegians and Danes from Nansen’s icecap crossing to the 1933 World Court verdict in The Hague Les attitudes groenlandaises envers les Norvégiens et les Danois, de la traversée de la calotte glacière par Nansen au jugement de 1933 de la Cour internationale à La Haye Karen Langgård Cultures inuit, gouvernance et cosmopolitiques Article abstract Inuit cultures, governance and cosmopolitics After Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930) crossed the Greenland icecap, he spent the Volume 38, Number 1-2, 2014 winter in Nuuk and impressed the Greenlanders not only by demonstrating his skill and daring in kayaking, but also by his openness to Greenlandic food, URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1028853ar culture, and traditions. Later on, when Danes and Norwegians came into DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1028853ar conflict over Greenland, Greenlanders supported the Danish colonial power against Norway, while at the same criticizing the Danes for not paying enough respect to Greenlanders during the process. Articles from the national See table of contents Greenlandic newspapers Atuagagdliutit and Avangnâmioĸ demonstrate that Greenlanders were open-minded towards Norwegians but critical towards Danes. They fully supported the latter as a colonial power against Norway, Publisher(s) while never refraining from the idea that Greenland remained their ethnic-national territory, even though for the time being it was colonized by Association Inuksiutiit Katimajiit Inc. the Danes. The author concludes that Greenlandic agency found in these Centre interuniversitaire d’études et de recherches autochtones (CIÉRA) newspapers is very relevant when negotiating today’s discourse on colonial Greenlanders. -

Nordlit 29, 2012 the PARADOXICAL DISCOURSE of LANGUAGE AND

THE PARADOXICAL DISCOURSE OF LANGUAGE AND SILENCE IN SOME CONTEMPORARY NORTH-AMERICAN TEXTS ON THE ARCTIC Fredrik Chr. Brøgger Between actuality and the imagined Arctic landscape lies a gap, an estuary, through which flow currents of ignorance and presumption. It is important to the well-being of our environment and to the understanding of ourselves as creatures in a living world that this gap be explored, that the distance between real and imagined landscape be apprehended and assessed. John Moss, “The Imagined Landscape” (1993) Remote and unknown lands have been the objects of both physical appropriation (for instance through exploration, scientific field work, and the like) and symbolic appropriation (for instance by the means of language, by translating what is initially unknown into one’s own familiar terms). With regard to the Euro-western exploration of the Arctic as well as other exotic regions of the world, material and symbolic appropriation went hand in hand and functioned as two sides of the same coin, although the linguistic “acquisition” of the land was usually far more unconscious, unreflective and habitual than its actual physical investigation. In contemporary North-American writing, however – no doubt influenced by post- modernist and post-colonial discourse – the problematic function of language itself in our constructions of the Arctic is felt to be an issue in need of urgent debate. 1. Silence and Language: Some Principal Observations Nowhere is the problem of language more obvious than when its subject is that of silence, which many writers regarded as a characteristic feature of the arctic regions that they were trying to describe.