The Native Greenlander-A Blending of Old Andnew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

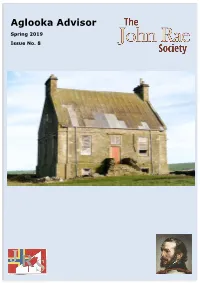

Aglooka Advisor Spring 2019

Aglooka Advisor Spring 2019 Issue No. 8 Aglooka Advisor Spring 2019 Issue No.8 President’s Report page 4 Eric Marwick: an obituary page 6 Polar Exploration: article by John Ramwell page 7 Dr John Rae Commemorated on an Unusual Scale: links to an article by Rognvald Boyd on the JRS website page 8 Two Art Exhibitions: article by Sigrid Appleby page 9 RICS honours John Rae: report by Fiona Gould page 10 Hall of Clestrain: archaeological report by Dan Lee page 10 Memories of Two Canadians: article by Anne Clark page 11 An Unexpected Guest: newspaper report from 1858 submitted by Fiona Sutherland page 12 Take the Torch: book review page 13 Arctic Return Expedition: update by David Reid page 14 Poster Competition: results page 15 Notices page 16 Photo on front cover by John Welburn, ABIPP, showing roof patches, new guttering and heavy-duty plastic covering on windows. - 2 - Patrons Dr Peter St John, The Earl of Orkney Ken McGoogan, Author Ray Mears, Author & TV Presenter Bill Spence, Lord Lieutenant of Orkney Sir Michael Palin Magnus Linklater CBE Board of Trustees (in alphabetical order by surname) Andrew Appleby — Jim Chalmers — Anna Elmy — Neil Kermode — Fiona Lettice Mark Newton — Norman Shearer Committee President — Andrew Appleby Chairman — Norman Shearer Honorary Secretary — Anna Elmy Honorary Treasurer — Fiona Lettice Webmaster and Social Media — Mark Newton Membership Secretary — Fiona Gould Administrative Secretary — Julie Cassidy Registered Office The John Rae Society 7 Church Road Stromness Orkney KW16 3BA Tel: 01856 851414 e-mail: [email protected] Newsletter Editor — Fiona Gould The views expressed in this newsletter are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editor or the Board of Trustees of the John Rae Society. -

October 22, 1947 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep October 1947 10-22-1947 Daily Eastern News: October 22, 1947 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1947_oct Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: October 22, 1947" (1947). October. 4. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1947_oct/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the 1947 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in October by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eastern State ·News • isor, left "Tell the Truth and Don't Be Afraid" 1y trip to VOL. XXXIII NO. 5 EASTERN ILLINOIS STATE COLLEGE ... CHARLESTON �ED., OCT. 22, 1947 .e of those :RN'S 83RD HomecomiQog 'fifoua time in histol-y of the t�e • ge. ast sutnme,r the nQ.me of the coHege'1fflll 'th..plans for wider Homecoming Festivities Begin Tomorrow turns . Olsen's Music for Arlene Swearingen Saturday Dance - Al,umni to Meet To Reign _as Queen GEORGE OLSEN and his "Music After'lun cheon ARLENE SWEARINGEN w i I I �s been of Tomorrow" will be the feature reign as queen over 1947 Home attraction of Eastern's Homecom Tenn. EASTERN'S ALUMNI associa- coming, Her attendants are June ing dance at 8:00 ·p. m. on Satur tion will hold an election of of Bubeck, senior; Harriett Smith, day, October 25, 1947. The Wo ficers at its business meeting, fol junior; Betty Kirkham, s'bpho men's gym will be decorated in lowing the Alumni luncheon in the more; and Alice Hanks, freshman. -

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

Touchet ..Educational Foundation

TOUCHET ..EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION TRIBAL TIMES I Spring 2009 Supporting Student Success The Touchet Educational Foundation (TEF) was officially formed as a non-profit 501©(3) organization in February 2003. Governed by a volunteer Board of Directors, the Board consists of eight representatives from agriculture, local businesses and alumni. The Touchet Educational Foundation Mission Statement is to provide financial support for Touchet students in pursuit of educational opportunities, and to encourage community support for higher education. The Board members donate hundreds of hours each year to provide leadership in achieving this mission. I 2008 - 2009 Board of Director and Representatives I Dave Reppe, President, was born and raised in Carol (Riley) Hopkins, Secretary, Touchet High Klamath Falls, OR. He graduated from Oregon School class of '87, graduated from University of State University with a B.S. in Agricultural Econom- Washington with BA in Business Administration. She, ics. He and his wife Sandy raised two sons that husband Chris and their sons Nickolas and Nathan graduated from Touchet High School, Doug in '86 returned to the Walla Walla valley in 2000. Carol has and Darin in '92. Dave also develops and distrib- volunteered as the Secretary since 2003. utes the scholarship applications. Doug Loney, Vice President, Touchet High Julie McCubbins, Treasurer, was born and raised School class of "80, and '86 graduate of Eastern in Walla Walla. She graduated from Walla Walla Com- Washington University. He and his wife Roberta are munity College in '82. Julie is married to Michael raising two future Touchet High School grads, Ian in McCubbins (class of '81). -

Greenland Explorer

GREENLAND EXPLORER Valleys and Fjords EXPEDITION IN BRIEF The Trip Overview Meet locals along the west coast of Greenland and experience traditional Inuit settlements Visit the Ilulissat Icefjord, a UNESCO World Heritage Site The west coast of Greenland is Europe’s final frontier, and sailing along it is Explore historic places from Norse the best way to sample its captivating history, enthralling wildlife and distinct and Viking eras culture. Explore places from the Norse and Viking eras, experience the Spot arctic wildlife, such as whales, birds and seals Ilulissat Icefjord—a UNESCO World Heritage Site— and visit two Greenland Cruise in a Zodiac to get up close to communities, encountering an ancient culture surviving in a modern world. glaciers, fjords, icebergs and more For trip inquiries, speak to our Polar Travel Advisers at 1. 844.205.0837 | Visit QuarkExpeditions.com for more details or get a free quote here. and geography of Greenland, your next Itinerary stop. Join expedition staff on deck and on the bridge as they look out for whales and seabirds, get to know your fellow Ban Bay GREENLAND DAY 1 | ARRIVE IN guests or simply take in the natural REYKJAVIK, ICELAND ARCTIC beauty that surrounds you. CIRCLE Arrive in the Icelandic capital in the Eqip Sermia Ilulissat morning and make your way to your DAY 4 | EAST GREENLAND Sisimiut Kangerlussuaq Experience a true arctic ghost town Itilleq included hotel. You will have the day Scoresby Sund to explore the city on your own. In when we visit the abandoned settlement Nuuk of Skjoldungen, where inhabitants the evening, join us at your hotel for a Skjoldungen Denmark Strait welcome briefing. -

The Greenlander of Today 5

Top-Sukkertoppen, a west Greenland settlement, is located on rocky terrain. It is the centre of a valuablesealing and cod-salting industry. Bottom-Godthaab, capital of Greenland, was founded by the Danish missionary Hans Egede in 1721. This view shows the older part of the town including the hospital to the left. .. THE GREENLANDER OFTODAY* By Eske Brun. The Greenland Administration, Copenhagen, Denmark. SHOULD like to begin by saying something about the first and most I serious error generally made about Greenland, and the one which is, I think, the most difficult to eradicate: It is popularly believed that it is cold in Greenland, so cold that wherever and whenever you are there you are frozen stiff, and that there is nothing there but ice and snow. This idea of Greenland as an enormous lump of ice is largely due to the ice-cap. Five-sixths of Greenland’s two million square kilometers are covered by this ice-cap. There is so much ice there that, if it melted, the oceans and seasall over theworld would rise eight meters. The existence of the ice-cap is not due to any excessive cold in Greenland, but mainly to the considerable height of the country, the average height of the surface of the ice-cap being about 2000 meters, and to the heavy snowfall. Paradoxical as it may seem ,the ice-cap is thicker in southern Greenland than in northern Greenland, because the snowfall is heavier in the south. The largest continuous tracts of land not covered with ice are to be found in Peg-yland on the northern coast of the country. -

På Isen Amundsen Af Niels Aage Jensen – 99.4 – Jubilæumsliste 2011

Kuldegys på isen Amundsen af Niels Aage Jensen – 99.4 – jubilæumsliste 2011. 334 sider En bog om Roald Amundsens liv som opdagelsesrejsende og polarforsker. For 100 år siden – om eftermiddagen den 14. december 1911 - lykkedes Hans skibsekspeditioner og forsøg med transpolare flyvninger beskrives, det Roald Amundsen at blive det første menneske i verden, som nåede ligesom hans sammensatte personlighed skildres. frem til Sydpolen. Han vandt kapløbet foran Robert Scott, der kom en måned for sent og omkom på hjemvejen. Den fremmede fortryller - beretning om Knud Rasmussen og hans to folk Tag en rejse tilbage i tiden til de store polarforskere, der har skrevet sig ind af Ebbe Kløvedal Reich – 99.4 i historien ved deres ufattelige bedrifter på isen både i syd og nord: norske 1995. 296 sider Roald Amundsen, britiske Robert Scott, danske Knud Rasmussen m.fl. Et portræt af grønlandsfareren og privatpersonen Knud Rasmussen, der, som forfatteren skriver i forordet, er tegnet på afstand og med frihånd: Jeg har udvalgt en række biografier om polarforskerne og deres ekspe- ”Jeg har opsøgt den tilgængelige viden, men en del af den har jeg udeladt”. ditioner og fundet bøger og film om is, sne og kulde, klimaforhold og Ønsker du at læse om Knud Rasmussens eventyrlige liv og gerninger, hvor klimaforandringer i polarområderne og på Grønland. Til sidst er en liste vægten er på den gode historie, er denne biografi et godt bud. over relevante hjemmesider. Den sidste dagbog Så er du til kolde gys og facts, så rigtig god fornøjelse. af Rober Falcon Scott – 99.4 2009. 473 sider De fulde dagbogsoptegnelser fra Robert F. -

Greenland's Project Independence

NO. 10 JANUARY 2021 Introduction Greenland’s Project Independence Ambitions and Prospects after 300 Years with the Kingdom of Denmark Michael Paul An important anniversary is coming up in the Kingdom of Denmark: 12 May 2021 marks exactly three hundred years since the Protestant preacher Hans Egede set sail, with the blessing of the Danish monarch, to missionise the island of Greenland. For some Greenlanders that date symbolises the end of their autonomy: not a date to celebrate but an occasion to declare independence from Denmark, after becoming an autonomous territory in 2009. Just as controversial as Egede’s statue in the capital Nuuk was US President Donald Trump’s offer to purchase the island from Denmark. His arrogance angered Greenlanders, but also unsettled them by exposing the shaky foundations of their independence ambitions. In the absence of governmental and economic preconditions, leaving the Realm of the Danish Crown would appear to be a decidedly long-term option. But an ambitious new prime minister in Nuuk could boost the independence process in 2021. Only one political current in Greenland, tice to finances. “In the Law on Self-Govern- the populist Partii Naleraq of former Prime ment the Danes granted us the right to take Minister Hans Enoksen, would like to over thirty-two sovereign responsibilities. declare independence imminently – on And in ten years we have taken on just one National Day (21 June) 2021, the anniver- of them, oversight over resources.” Many sary of the granting of self-government people just like to talk about independence, within Denmark in 2009. -

Knud Rasmussen Glacier Status Analysis Based on Historical Data and Moving Detection Using RPAS

applied sciences ArticleArticle KnudKnud RasmussenRasmussen GlacierGlacier StatusStatus AnalysisAnalysis BasedBased onon HistoricalHistorical DataData andand MovingMoving DetectionDetection UsingUsing RPASRPAS KarelKarel PavelkaPavelka **, Jaroslav, Jaroslav Šedina Šedina and and Karel Karel Pavelka Pavelka,, Jr Jr.. FacultyFaculty ofof CivilCivil Engineering,Engineering, CzechCzech TechnicalTechnical University University in in Prague, Prague, Thakurova Thakurova 7, 7, 16629 16629 Prague, Prague Czech, Republic; [email protected] Republic; [email protected] (J.Š.); [email protected] (J.Š.) [email protected] (K.P.J.) (K.P.J.) ** Correspondence:Correspondence: [email protected]; [email protected]; Tel.: Tel.: +420-608-211-360 +420-608-211-360 Abstract:Abstract: ThisThis articlearticle discussesdiscusses partialpartial resultsresults ofof anan internationalinternational scientificscientific expeditionexpedition toto GreenlandGreenland thatthat researchedresearched thethe geography,geography, geodesy,geodesy, botany,botany, andand glaciologyglaciology ofof thethe area.area. TheThe resultsresults herehere focusfocus onon the photogrammetrical results results obtained obtained with with the the eBee eBee drone drone in in the the eastern eastern part part ofof Greenland Greenland at atthe the front front of ofthe the Knud Knud Rasmussen Rasmussen Glacier Glacier and and the theuse useof archive of archive image image data data for monitoring for monitoring the con- the conditiondition of this of thisglacier glacier.. In these In theseshort- short-termterm visits to visits the site, to the the site, possibility the possibility of using ofa drone using is a discussed drone is discussedand the results and the show results not showonly the not flow only thespeed flow of speedthe glacier of the but glacier alsobut the alsoshape the and shape structure and structure from a fromheight a heightof up to of 200 up m. -

Northwest Passage: in the Footsteps of Franklin

NORTHWEST PASSAGE: IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF FRANKLIN Winding your way through the icy channels of the legendary Northwest Passage is history brought to life. On this compelling 17-day journey aboard the game-changing new vessel Ultramarine, passengers retrace the steps of the intrepid Franklin Expedition, which left the shores of England in 1845 in search of the last unexplored section of the Northwest Passage--only to become permanently icebound. Its discovery more than a century and a half later was a much-celebrated moment in polar history. On Ultramarine, guests benefit from two twin-engine helicopters that will provide spectacular aerial views of the Arctic landscape, the most extensive portfolio of adventure options in the industry, more outdoor wildlife viewing spaces than any other expedition ship its size, and 20 quick-launching Zodiacs to get you closer to ancient glaciers, dramatic fjords and towering icebergs. Explore colorful Greenlandic villages, and shop for traditional Inuit handicrafts. Hike the endless Arctic backdrop and marvel at the vast, colorful tundra. Keep your eyes peeled for the elusive and majestic creatures that make their home in this wilderness, such as whales, walrus, muskoxen and polar bears. Come aboard Ultramarine, follow in the footsteps of Franklin's legendary Arctic voyage, and return home with memories to last a lifetime. MANDATORY TRANSFER PACKAGE INCLUDES: One night's pre-expedition airport hotel accommodation in Toronto 01432 507 280 (within UK) [email protected] | small-cruise-ships.com Group -

Introduction the Warrior Worship Idea Is Simply That a Surrendered Warrior Is a Victorious Warrior

Introduction The Warrior Worship idea is simply that a surrendered warrior is a victorious warrior. A surrendered warrior life is a powerful and power-filled life. Fully giving our lives over to our amazing King Jesus is the kind of obedience He requires of His followers. It’s what Jesus means when He says “If you love Me, you’ll obey My commands” (John 14:15, GNT). That kind of commitment begins with believing “all Scripture is breathed out by God and is useful to teach us what is true” (2 Timothy 3:16, ESV). What amazing payoffs in this life and the next for those that serve Jesus above anything else! His promise is “no eye has seen, no ear has heard, no mind has imagined the things God has prepared for those that love Him” (1 Corinthians 2:9, NLT). There is simply no way to live as a warrior for Jesus Christ without reading, memorizing, digesting and living the truths of God’s Word. “The Word of God is alive and active, sharper than any double-edged sword able to expose our innermost thoughts and desires” (Hebrews 4:12, NIV). That’s why we’re so excited to offer this devotional to go along with the Warrior Worship original worship music project “Stronger” (in partnership with Warrior Leadership Summit 2021). God’s warriors - you! - have so much potential! “You are God’s masterpiece, created in Christ Jesus to do good works He prepared in advance for you to do” (Ephesians 2:10, NLT). Loving and living the Bible unlocks the amazing potential and future God has for you! The guy who wrote these Bible studies, Jesse Colucci, in addition to writing a lot of Warrior Worship music, is one of those warriors who loves and lives God’s Word.