High Arctic Sovereignty Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aglooka Advisor Spring 2019

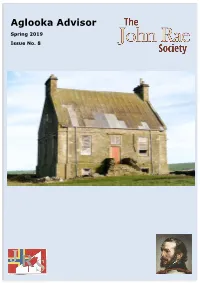

Aglooka Advisor Spring 2019 Issue No. 8 Aglooka Advisor Spring 2019 Issue No.8 President’s Report page 4 Eric Marwick: an obituary page 6 Polar Exploration: article by John Ramwell page 7 Dr John Rae Commemorated on an Unusual Scale: links to an article by Rognvald Boyd on the JRS website page 8 Two Art Exhibitions: article by Sigrid Appleby page 9 RICS honours John Rae: report by Fiona Gould page 10 Hall of Clestrain: archaeological report by Dan Lee page 10 Memories of Two Canadians: article by Anne Clark page 11 An Unexpected Guest: newspaper report from 1858 submitted by Fiona Sutherland page 12 Take the Torch: book review page 13 Arctic Return Expedition: update by David Reid page 14 Poster Competition: results page 15 Notices page 16 Photo on front cover by John Welburn, ABIPP, showing roof patches, new guttering and heavy-duty plastic covering on windows. - 2 - Patrons Dr Peter St John, The Earl of Orkney Ken McGoogan, Author Ray Mears, Author & TV Presenter Bill Spence, Lord Lieutenant of Orkney Sir Michael Palin Magnus Linklater CBE Board of Trustees (in alphabetical order by surname) Andrew Appleby — Jim Chalmers — Anna Elmy — Neil Kermode — Fiona Lettice Mark Newton — Norman Shearer Committee President — Andrew Appleby Chairman — Norman Shearer Honorary Secretary — Anna Elmy Honorary Treasurer — Fiona Lettice Webmaster and Social Media — Mark Newton Membership Secretary — Fiona Gould Administrative Secretary — Julie Cassidy Registered Office The John Rae Society 7 Church Road Stromness Orkney KW16 3BA Tel: 01856 851414 e-mail: [email protected] Newsletter Editor — Fiona Gould The views expressed in this newsletter are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editor or the Board of Trustees of the John Rae Society. -

Demande De La CNER Faisant L'objet D'un Examen Préalable

Demande de la CNER faisant l’objet d’un examen préalable #125472 One Ocean Expeditions - Arctic 2019 cruise season Type de demande : New Type de projet: Tourisme Date de la demande : 5/30/2019 5:47:04 PM Period of operation: from 0001-01-01 to 0001-01-01 Autorisations proposées: from 0001-01-01 to 0001-01-01 Promoteur du projet: Aaron Lawton One Ocean Expeditions 38141 2nd Ave Squamish British Columbia V8B 0A6 Canada Téléphone :: 6043904900, Télécopieur :: DÉTAILS Description non technique de la proposition de projet Anglais: Expedition cruise tourism in the Canadian Arctic with a maximum of 146 passengers and 25 staff from around the world. We plan to operate 5 voyages in Nunavut on the RCGS Resolute from July 2019 through to September 2019. Ship visits are concentrated in ice-free zones and in arctic communities. Visits ashore last generally no longer than three hours.Our ship, the RCGS Resolute will drift or drop anchor while passengers disembark into small inflatable zodiacs. Passengers will cruise in zodiacs or will land on shore where appropriate. Français: Description du Projet :Nos opérons un vaisseau de tourisme style expédition capable de transporter un maximum de 146 passagers et 25 employés que nous employons de partout dans le monde. Nous planifions opérer 5 voyages dans le Nunavut en 2019 abord le RCGS Resolute à partir du mois de juillets jusqu’au mois de septembre. Les visites à bateau sont concentrées dans les zones d’eau libre ou se trouve la plupart des communautés de L’arctique. Nos visites ne durent pas plus que trois heures. -

Seismic Reflection Profiles from Kane to Hall Basin, Nares Strait: Evidence for Faulting

Polarforschung 74 (1-3), 21 – 39, 2004 (erschienen 2006) Seismic Reflection Profiles from Kane to Hall Basin, Nares Strait: Evidence for Faulting by H. Ruth Jackson1, Tim Hannon1, Sönke Neben2, Karsten Piepjohn2 and Tom Brent3 Abstract: Three major tectonic boundaries are predicted to be present beneath durch eine folgende kompressive Phase reaktiviert wurde. Als Arbeitshypo- the waters of this segment of Nares Strait: (1) the orogenic front of the Paleo- these fassen wir die oberflächennahen Teile dieses Systems als Stirn der Plat- zoic Ellesmerian Foldbelt between thrust sheets on Ellesmere Island and flat- tengrenze zwischen Nordamerika und Grönland auf. lying foreland rocks on Greenland, (2) the supposed sinistral strike-slip plate boundary of Paleocene age between the Ellemere Island section of the North America plate and the Greenland plate, and (3) the orogenic front of the Eocene to Oligocene Eurekan Foldbelt that must lie between thrust tectonics INTRODUCTION on Ellesmere Island and undeformed rocks of Greenland. To understand this complicated situation and to look for direct evidence of the plate boundary, The Late Cretaceous and Tertiary deformation on Ellesmere new seismic reflection profiles were collected and, together with industry data in the south, interpreted. The profiles are clustered in three areas controlled by Island (Fig. 1) called the Eurekan Orogeny has been attributed the distribution of the sea ice. Bathymetry is used to extrapolate seismic to the counter clockwise rotation of Greenland (e.g., OKULITCH features with a topographic expression between the regions. Based on high- & TRETTIN 1991). However reconciling the geology on oppo- resolution boomer and deeper penetration airgun profiles five seismic units are mapped. -

Internal Frost Damage in Concrete - Experimental Studies of Destruction Mechanisms

Internal frost damage in concrete - experimental studies of destruction mechanisms Fridh, Katja 2005 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Fridh, K. (2005). Internal frost damage in concrete - experimental studies of destruction mechanisms. Division of Building Materials, LTH, Lund University. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 LUND INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY LUND UNIVERSITY Division of Building Materials INTERNAL FROST DAMAGE IN CONCRETE Experimental studies of destruction mechanisms Katja Fridh Report TVBM-1023 Doctoral thesis Lund 2005 ISRN LUTVDG/TVBM--05/1023--SE(1-276) ISSN 0348-7911 TVBM ISBN 91-628-6558-7 Lund Institute of Technology Telephone: 46-46-2227415 Division of Building Materials Telefax: 46-46-2224427 Box 118 www.byggnadsmaterial.lth.se SE-221 00 Lund, Sweden Preface The work presented here was carried out at the Division of Building Materials at the Lund Institute of Technology. -

Demande De La CNER Faisant L'objet D'un Examen Préalable

Demande de la CNER faisant l’objet d’un examen préalable #125330 MS SILVER CLOUD Arctic and Greenland Expedition Cruise (Voyage 1819, 18 August-03 September 2018) and Canada and New England Expedition Cruise (Voyage 1820, 03-18 September 2018) Type de demande : New Type de projet: Tourisme Date de la demande : 4/9/2018 1:41:37 PM Period of operation: from 0001-01-01 to 0001-01-01 Autorisations proposées: from 0001-01-01 to 0001-01-01 Promoteur du projet: Conrad Combrink Silversea Cruises Ltd Wells Fargo Center, 333 Southeast 2nd Avenue, Suite 2600 Miami Florida 33131 USA Téléphone :: 001 954 225 2567, Télécopieur :: 001 954 522 4499 DÉTAILS Description non technique de la proposition de projet Anglais: See attached Non-technical Project Proposal in English Français: See attached Non-technical Project Proposal in French Inuktitut: See attached Non-technical Project Proposal in Inuktitut Personnel Personnel on site: 960 Days on site: 12 Total Person days: 11520 Operations Phase: from 2018-08-16 to 2018-09-08 Activités Emplacement Type Statut des Historique du site Site à valeur Proximité des d’activité terres archéologique ou collectivités les paléontologique plus proches et de toute zone protégée Iqaluit Tourism Crown Capital of Nunavut Capital of Nunavut Capital of Activities Nunavut Pond Inlet Tourism Crown A small, N/A N/A Activities predominantly Inuit community in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, and is located in northern Baffin Island. Buchan Gulf Marine Based Marine N/A N/A Pond Inlet Activities Bylot Island Tourism Inuit Owned Unknown Unknown Pond Inlet we Activities Surface Lands believe is the nearest community. -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Re-Evaluation of Strike-Slip Displacements Along and Bordering Nares Strait

Polarforschung 74 (1-3), 129 – 160, 2004 (erschienen 2006) In Search of the Wegener Fault: Re-Evaluation of Strike-Slip Displacements Along and Bordering Nares Strait by J. Christopher Harrison1 Abstract: A total of 28 geological-geophysical markers are identified that lich der Bache Peninsula und Linksseitenverschiebungen am Judge-Daly- relate to the question of strike slip motions along and bordering Nares Strait. Störungssystem (70 km) und schließlich die S-, später SW-gerichtete Eight of the twelve markers, located within the Phanerozoic orogen of Kompression des Sverdrup-Beckens (100 + 35 km). Die spätere Deformation Kennedy Channel – Robeson Channel region, permit between 65 and 75 km wird auf die Rotation (entgegen dem Uhrzeigersinn) und ausweichende West- of sinistral offset on the Judge Daly Fault System (JDFS). In contrast, eight of drift eines semi-rigiden nördlichen Ellesmere-Blocks während der Kollision nine markers located in Kane Basin, Smith Sound and northern Baffin Bay mit der Grönlandplatte zurückgeführt. indicate no lateral displacement at all. Especially convincing is evidence, presented by DAMASKE & OAKEY (2006), that at least one basic dyke of Neoproterozoic age extends across Smith Sound from Inglefield Land to inshore eastern Ellesmere Island without any recognizable strike slip offset. INTRODUCTION These results confirm that no major sinistral fault exists in southern Nares Strait. It is apparent to both earth scientists and the general public To account for the absence of a Wegener Fault in most parts of Nares Strait, that the shape of both coastlines and continental margins of the present paper would locate the late Paleocene-Eocene Greenland plate boundary on an interconnected system of faults that are 1) traced through western Greenland and eastern Arctic Canada provide for a Jones Sound in the south, 2) lie between the Eurekan Orogen and the Precam- satisfactory restoration of the opposing lands. -

Geographical Report of the Crocker Land Expedition, 1913-1917

5.083 (701) Article VL-GEOGRAPHICAL REPORT OF THE CROCKER LAND EXPEDITION, 1913-1917. BY DONALD B. MACMILLAN CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION......................................................... 379 SLEDGE TRIP ON NORTH POLAR SEA, SPRING, 1914 .......................... 384 ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATIONS-ON NORTH POLAR SEA, 1914 ................ 401 ETAH TO POLAR SEA AND RETURN-MARCH AVERAGES .............. ........ 404 WINTER AND SPRING WORK, 1915-1916 ............. ......................... 404 SPRING WORK OF 1917 .................................... ............ 418 GENERAL SUMMARY ....................................................... 434 INTRODUCTJON The following report embraces the geographical work accomplished by the Crocker Land Expedition during -four years (Summer, 19.13, to Summer, 1917) spent at Etah, NortJaGreenland. Mr. Ekblaw, who was placed in charge of the 1916 expeditin, will present a separate report. The results of the expedition, naturally, depended upon the loca tion of its headquarters. The enforced selection of Etah, North Green- land, seriously handicapped the work of the expedition from start to finish, while the. expenses of the party were more than doubled. The. first accident, the grounding of the Diana upon the coast of Labrador, was a regrettable adventure. The consequent delay, due to unloading, chartering, and reloading, resulted in such a late arrival at Etah that our plans were disarranged. It curtailed in many ways the eageimess of the men to reach their objective point at the head of Flagler Bay, te proposed site of the winter quarters. The leader and his party being but passengers upon a chartered ship was another handicap, since the captain emphatically declared that he would not steam across Smith Sound. There was but one decision to be made, namely: to land upon the North Greenland shore within striking distance of Cape Sabine. -

Innhold • Karl Johan • Nei, TUBFRIM Er Ikke Nedlagt • 3

KILDENTidsskrift for Oslo Guideforening sommernummer 2011 Foto: Wenche M. Wangen Foto: Wenche • • Området rundt Solli plass Innhold • Karl Johan • Nei, TUBFRIM er ikke nedlagt • 3. juni 2011 - Brann og redning 150 år. • Tøyengata – et nyrikt stykke Norge • Kvinnedag, Rogstad og Bonnevie i jubileumsåret 2011 • Skjulte Grosch-skatter i Storgata • Østensjøvannet • Intervju med ordføreren • Alnaelva, en av Oslos viktigste, men ”glemte” elver. • Uret ved Universitetsplassen • Guidefi losofi – et hjertesukk • Statuene på Universitetsplassen • Ekeberg – Oslos viktigste fjell • Akershus slott og festning • Hvordan Frammuseet ble til og Framkomitéens rolle. • Norrøn mytologi – Skiguden Ull • Statsbesøk på Fram. • Munch på Tøyen – en sjokkerende beretning • Kirkerovet i Mariakirken i Oslo høsten 1529 • Munch i Universitetets Aula. • Eksplosjonsulykken i Kings Bay-gruven på Svalbard • Navnet er Operatunnelen • Politiske ettervirkninger av Kings Bay-ulykken 1 1 STYRET I OSLO GUIDEFORENING INNHOLDSFORTEGNELSE Styret i Oslo Guideforening Marie B. Berg Arild Eugen Johansen Kirsten Elmar Mikkelsen Norges Guideforbunds landsmøte/årsmøte 2011 ..........................................................................................................................................................................5 2010/11: (nestleder) (styremedlem) (varamedlem) Tøyengata – et nyrikt stykke Norge av Tone Huse. Wenche M. Wangen .....................................................................................................................................6 -

CURRENT RESEARCH C Resources Natural Anada Geological Surveyofcanada C Naturelles Ressources Anada

Geological Survey of Canada CURRENT RESEARCH 2006-G Geological Survey of Canada Radiocarbon Dates XXXV Collated by R. McNeely 2006 CURRENT RESEARCH Natural Resources Ressources naturelles Canada Canada ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2006 ISSN 1701-4387 Catalogue No. M44-2006/G0E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43811-6 A copy of this publication is also available for reference by depository libraries across Canada through access to the Depository Services Program's Web site at http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca A free digital download of this publication is available from GeoPub: http://geopub.nrcan.gc.ca/index_e.php Toll-free (Canada and U.S.A.): 1-888-252-4301 Critical reviewers L. Dredge Author’s address R. McNeely Geological Survey of Canada Terrain Sciences Division 601 Booth Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0E8 Publication approved by GSC Northern Canada Original manuscript submitted: 2005-12-15 Final version approved for publication: 2006-01-10 Correction date: All requests for permission to reproduce this work, in whole or in part, for purposes of commercial use, resale, or redistribution shall be addressed to: Earth Sciences Sector Information Division, Room 402, 601 Booth Street, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0E8. This date list, GSC XXXV, is the twenty-fourth to be published directly by the Geological Survey of Canada. Lists prior to GSC XII were published first in the journal Radiocarbon and were reprinted as GSC Papers. The lists through 1967 (GSC VI) were given new pagination, whereas lists VII to XI (1968 to 1971) were reprinted with the same pagination. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 2 Acknowledgments . -

An Experimental Study of Ice-Bed Separation During Glacial Sliding Benjamin Brett Etp Ersen Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 An experimental study of ice-bed separation during glacial sliding Benjamin Brett etP ersen Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons, and the Geophysics and Seismology Commons Recommended Citation Petersen, Benjamin Brett, "An experimental study of ice-bed separation during glacial sliding" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12701. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12701 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An experimental study of ice-bed separation during glacial sliding by Benjamin Brett Petersen A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Geology Program of Study Committee: Neal R. Iverson, Major Professor Igor Beresnev Carl E. Jacobson Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright © Benjamin Brett Petersen, 2012. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii ABSTRACT iv CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Ice-bed separation 1 1.2 Sliding models 2 1.3 Hydrology models 5 1.4 Quarrying 8 1.5 Experimental studies of cavitation 9 1.6 Motivation and objectives 10 CHAPTER 2. METHODS 12 2.1 The ring-shear device 12 2.2 Procedure 19 2.3 Data processing 25 CHAPTER 3. -

Reconstructing the Confluence Zone Between Laurentide and Cordilleran Ice Sheets Along the Rocky Mountain Foothills, Southwest Alberta

This is a repository copy of Reconstructing the confluence zone between Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets along the Rocky Mountain Foothills, southwest Alberta. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/105138/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Utting, D., Atkinson, N., Pawley, S. et al. (1 more author) (2016) Reconstructing the confluence zone between Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets along the Rocky Mountain Foothills, southwest Alberta. Journal of Quaternary Science, 31 (7). pp. 769-787. ISSN 0267-8179 https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.2903 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Reconstructing the confluence zone between Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets along the Rocky Mountain Foothills, south-west Alberta Daniel J. Utting1, Nigel Atkinson1, Steven Pawley1, Stephen J.