Krishna Prasadam: the Transformative Power of Sanctified Food in the Krishna Consciousness Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1994 Page 1 of 6 1994 06/10/2017

1994 Page 1 of 6 Home Srila Prabhupada ISKCON GBC Ministries Strategic Planning ILS News Resources Multimedia Contact Welcome to Mingle! This is a sample layout using a "Top Graphic". The background image may not appear if your theme is installed in a sub-directory, but not to worry! You can specify the path to your images from the admin. To edit this area, go to "Appearance > Design Settings > Top Graphics". 1994 FEBRUARY 9, 2012 NTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS Founder-Acarya: His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada RESOLUTIONS OF THE GOVERNING BODY COMMISSION Annual General Meeting — 1994 — Mayapur, India 1. That Madhu Sevita Prabhu is appointed as full GBC member. 2. That Romapad Swami is appointed as full GBC member. 3. That Naveen Krishna Prabhu is appointed as Acting GBC member. 4. That Bhakti Raghava Swami is appointed as Assistant GBC member for an additional year. 5. That Rohini Suta Prabhu is appointed as Acting GBC member. 8. That the GBC Body gives its blessings to the design for the Temple of the Vedic Planetarium presented by the Mayapur Development Committee, and further approves the use of Western architects as described in the presentation. 9. That Raghubhir Das is permitted to take sannyas this year. 10. That Birsingha Das is permitted to take sannyas this year. 11. That the GBC Executive Officers for 1994-95 are as follows: Chairman Jagadisa Maharaj Vice Chairman Naveen Krishna Das Executive Secretary Tamal Krishna Goswami 12. That Mahamantra Das is approved to remain on the three year sannyas waiting list. 13. -

“This Is My Heart” Patita Uddharana Dasa, Editor / Compiler

“This Is My Heart” Patita Uddharana dasa, Editor / Compiler “This Is My Heart” Remembrances of ISKCON Press …and other relevant stories Manhattan / Boston / Brooklyn 1968-1971 1 Essays by the Assembled Devotees “This Is My Heart” Remembrances of ISKCON Press …and other relevant stories Manhattan / Boston / Brooklyn 1968-1971 Patita Uddharana Dasa Vaishnava Astrologer and Author of: 2 -The Bhrigu Project (5 volumes) (with Abhaya Mudra Dasi), -Shri Chanakya-niti with extensive Commentary, -Motorcycle Yoga (Royal Enflied Books) (as Miles Davis), -What Is Your Rashi? (Sagar Publications Delhi) (as Miles Davis), -This Is My Heart (Archives free download) (Editor / Compiler), -Shri Pushpanjali –A Triumph over Impersonalism -Vraja Mandala Darshan – Touring the Land of Krishna -Horoscope for Disaster (ms.) -Bharata Darshan (ms.) ―I am very pleased also to note your appreciation for our Bhagavad-gita As It Is, and I want that all of my students will understand this book very nicely. This will be a great asset to our preaching activities.‖ (-Shrila Prabhupada, letter to Patita Uddharana, 31 May 1969) For my eternal companion in devotional service to Shri Guru and Gauranga Shrimati Abhaya Mudra Devi Dasi A veritable representative of Goddess Lakshmi in Krishna’s service without whose help this book would not have been possible ―We are supposed to take our husband or our wife as our eternal companion or assistant in Krishna conscious service, and there is promise never to separate.‖ (Shrila Prabhupada, letter 4 January 1973) (Shri Narada tells King Yudhishthira:) ―The woman who engages in the service of her 3 husband, following strictly in the footsteps of the goddess of fortune, surely returns home, back to Godhead, with her devotee husband, and lives very happily in the Vaikuṇṭha planets.‖ “Shrila Prabhupada” by Abhaya Mudra Dasi “Offer my blessings to all the workers of ISKCON Press because that is my life.” (-Shrila Prabhupada, letter 19 December 1970) 4 Table of Contents Introduction ―Books Any Man Would Be Proud to Have‖ ……... -

The Qualities of God and His Devotees Lord Chaitanya

PSHE Yearly Overview 2019-2020 Reception Autumn 1 Autumn 2 Spring 1 Spring 2 Summer 1 Summer 2 Theme Lord Rama The deity is Krishna Intro to Krishna at Avanti Lord Krishna Lord Chaitanya Avatars -The qualities of God and his -Relating with Krishna -God as a person -The teachings of God -Values exemplified by God devotees Unit Descriptor Allowing 3 weeks to settle in, children Children will learn more about who Children will learn the story of Lord Children will learn about Lord Children will explore how Lord Krishna In preparation for taking on greater will get an introduction to worship and Krishna is. They will hear stories about Rama. They will take examples of Chaitanya’s pastimes as a baby and loves to play ‘Dress-up’. They have responsibility for school and classroom key aspects of the faith that they will Krishna’s heroic acts and pastimes in behaviour from key characters such as youth. They will draw similarities learned about Krishna ‘dressing up’ as deities, children will explore why and encounter at Avanti. Children will learn Vrindavan. They will develop an Rama and Hanuman and others. And between the pastimes of Krishna and Rama and Lord Chaitanya, now they will how we worship the deity and how through stories and practical activities understanding of Krishna as a person then discuss how they can apply these Lord Chaitanya as mystical or learn through stories and practical deity can reciprocate with us. about how to worship Krishna by and how he interacts with his friends, principles eg. How can we be a good superhuman. -

Exploring the Identity of the Hare Krishna Devotees Beyond Race, Language and Culture

THE ENDURING SELF: EXPLORING THE IDENTITY OF THE HARE KRISHNA DEVOTEES BEYOND RACE, LANGUAGE AND CULTURE by S.M. Ramson Student number: 205519769 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree (Religion and Social Transformation) In the School of Religion and Theology Faculty of Humanities University of Kwazulu Natal JOINT PROMOTERS: Professor P. Kumar Professor R. Sookrajh January 2006 i DECLARATION I, do hereby declare that this dissertation, which is submitted to the university for the degree of Master of Arts (Religion and Social Transformation), has not been previously submitted by me for a degree at any other university, and all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of a complete reference. S.M. Ramson Researcher Professor P. Kumar Professor R. Sookrajh ii DEDICATION This research is dedicated to His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder acharya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (The Hare Krishna Movement) who in the face of extreme difficulty presented the Gaudiya Vaisnava science of Self Realization and devotion to the Western world, whose courage, insights, perspicacity, purity and love forms the example that I wish to pursue. iii ACKNO WLEDGEMENTS It does not take the stance of a social scientist to understand that one of the enduring features of social dynamics amongst humans is the ability to extend themselves selflessly, and sometimes, even with great effort make sacrifices simply for the progress of others. There is no scale on which I can rate such benefaction, except to understand that I am overwhelmed by a sense of gratitude to several individuals to whom I wish to sincerely express my heartfelt appreciation. -

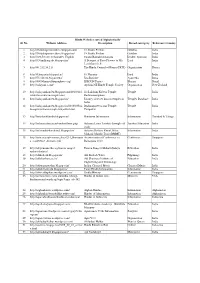

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Srila Prabhupada His Movement And

Dedication Dedicated to my spiritual master, His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, Acharya of the Brahma-Gaudiya Vaishnava Sampradaya, Founder- Acharya of the Hare Krishna Movement. “He lives forever by his divine instructions, and the follower lives with him.” mukam karoti vachalam pangum langhayate girim yat-kripa tam aham vande sri gurum dina tarinam “By the mercy of the Guru even a dumb man can become a great speaker, and even a lame man can cross mountains.” “All my disciples will take the legacy. If you want, you can also take it. Sacrifice everything. I, one, may soon pass away. But they are hundreds, and this movement will increase. It is not that I give an order, ‘Here is the next leader.’ Anyone who follows the previous leadership is the leader…. All of my disciples are leaders, as much as they follow purely. If you want to follow, you can also lead. But you don’t want to follow. Leader means one who is a first class disciple. Evam parampara praptam. One who is following is perfect.” (Srila Prabhupada, Back to Godhead magazine, Vol. 13, No. 1-2) Phalgun Krishna Panchami By His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada The following is an offering of five prayers glorifying special characteristics of Srila 108 Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati Goswami Thakur. Presented on the commemoration of his appearance at the Radha-Damodara temple, Vrindavan, India in 1961. First Vasistya 1. On this day, O my master, I made a cry of grief; I was not able to tolerate the absence of my guru. -

Srila Prabhupada Tributes 2012

ÇRÉLA PRABHUPÄDA Celebrating the appearance day of our 2012 TRIBUTES 11AUG beloved spiritual master TRIBUTES PRABHUPÄDA ÇRÉLA “I have started the Krsna consciousness movement in America. But actually the original father of this movement is Lord Krsna Himself, since it was started a very long time ago but is coming down to human society by disciplic succession. If I have any credit in this connection, it does not belong to me personally, but it is due to my eternal spiritual master, His Divine Grace Om Visnupada Paramahamsa Parivrajakacarya 108 Sri Srimad Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Gosvami Maharaja Prabhupada.” — Çréla Prabhupäda, Preface, Bhagavad-gétä As It Is OÀ VIÑËUPÄDA ÇRÉ ÇRÉMAD FOUNDER-ÄCÄRYA 11AUG PARAMAHAÀSA A.C. OF THE INTERNATIONAL 2012 — ÇRÉLA PRABHUPÄDA© 2011 — SRILA TRIBUTES PRABHUPADA TRIBUTES PARIVRÄJAKÄCÄRYA BHAKTIVEDANTA SOCIETY FOR KRISHNA Design & layout byDesign www.inajardesign.com & layout by www.inajardesign.com 2012 AÑÖOTARA-ÇÄTA SWAMI PRABHUPÄDA CONSCIOUSNESS ÇRÉLA PRABHUPÄDA TRIBUTES ÇRÉLA PRABHUPÄDA Celebrating the appearance day of our 2012 TRIBUTES 11AUG beloved spiritual master First Printing, limited printing, 300 copies, 2012 The copyrights for the Tributes in this book remain with their respective authors. We wish to gratefully acknowledge the BBT for use of verses and purports from ®r…la Prabhup€da’s books. All such materials are © Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, Inc. www.sptributes.com Printed in England Design and layout by Jagannath Sharan das www.inajardesign.com 4 Credits CONTENTS The Tributes presented in this book are by devotees directly initi- ated by Srila Prabhupada. They are presented herein in a chrono- logical order by initiation date. Introduction ........................................................................ -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Padayatra Newsletter

ISKCON - The International Society for Krishna Consciousness Founder Acharya His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Newsletter 2016 WORLDWIDE PLEASE POST IN YOUR TEMPLE 50PADAYATRAS BY THE END OF 2016 FOR ISKCON 50TH BIRTHDAY Lord Krishna created us with half of our body made up of legs, so Ibelieve in using them for Him. I find there’s no better or more personal way to meet people than with the low-tech, highly organic approach of using your legs. The legs were made for walking and the mouth for speaking about the Absolute. What a perfect combination. Bhaktimarga Swami . Table of contents Editorial 1 by Lokanath Swami Celebrate ISKCON50 with padayatra 2 by Gaurangi Dasi Choose your padayatra 5 Niranjana Swami’s realisations 6 The most purifying program, 7 by Jaya Vijaya Dasa Walking for our teachers 8 by Bhaktimarga swami The Czech Republic survey 11 by Muni Priya Dasa and Nrsimha Caitanya Dasa The Padayatra questionnaire 13 People want to know, do we care about the environment 14 by Mukunda Goswami No plastic in Vraja 15 by Deena Bandhu Dasa The ecological padayatra camp 16 by Gaurangi Dasi The art of walking 17 by Gaurangi Dasi Prabhupada walking murti Walk the walk, poem 19 by Suresvara Dasa This newsletter is dedicated to Walking like barefoot with Leguano shoes 20 ISKCON Founder-Acarya, Palanquins and/or carts ? 21 His Divine Grace by Gaurangi Dasi A.C.Bhaktivedanta He’s the one we’ve been waiting for 26 by Srivas Dasa Swami Prabhupada. Scary encounters 26 by Bhaktimarga Swami Editor in Chief « Just keep walking down -

December/November

Contents Message from the President of Young Vaishnava Column ISKCON KwaZulu Natal Spiritual Chain 13 The Mercy of a Devotee 3 Book Review Features Miracle on Second Avenue 14 The Lion Guru 4 Share the Good Fortune! 5 Notice Board 15 God and Demigods Vaishnava Calendar 15 Goddess Durga 6 Srila Prabhupada Sri Sri Radha Radhanath Poster 8 On Book Distribution 16 Vedic Observer On the Cover: Inside the Indelible Impressions 10 Radha Radhanath Temple. Devotee Profile Come and visit us this summer to Offering One’s Youth to Krishna 11 experience spiritual serenity. We are open daily from 4.30am-9pm Vaishnava Kitchen and tours are free. Fruit Ice Lollies 12 Desire to Win passed me to get to the next approaching gambler. Editor’s Note This transcendental competition was fun and exciting for us, and just as entertaining for my grandmother It was a scorching hot summer’s day in 1980, when who was the designated adult supervisor. As the my sister, first cousin, grandmother and I (barely ten perspiration dripped from her wrinkled forehead, years old) loaded into my father’s navy blue station she stood in the hot sun, chanting on her japa beads wagon with a stack of the Hare Krishna Times, our and watching over us. monthly temple newsletter. That Saturday morning was no different from any other. The Summer My biggest inspiration was my older sister who Newsletter Marathon was in full swing and the desire regularly won in her age group. Our nama-hatta also to win the competition was insatiable. Whilst most won the group category for many years. -

Lord Krishna's Birthday Extravaganza

October 2011 Dedicated to His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, Founder-Acharya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness Lord Krishna’s Birthday Extravaganza During a very overcast month Bhaktivedanta Manor was blessed with two sunny days during the annual Janmastami festival. Around 60,000 pilgrims joined in the celebrations, with the majority present on the actual day itself, Monday 22 August. With a whole host of colourful performances and activities on offer, it was a field Srila Prabhupada: day for media - with hours of coverage across BBC, Sky News, ITN London “In the material world there Tonight, Radio 4, Radio Five Live and is keen competition between Channel 4. animal and animal, man Krishna is famous as the guardian of and man, community and cows and appropriately, this year's community, nation and festival featured the official launch of nation. But the devotees of the Ahimsa Dairy Foundation (ADF). the Lord rise above such Ahimsa means "not to harm", and ADF has established a herd of cows in Kent competitions. They do not which is known as the Ahimsa herd. compete with the materialist The cows produce milk for delivery because they are on the path and are protected from harms way and back to Godhead where slaughter. life is eternal and blissful. The Janmashtami festival was open to His Holiness Radhanath Swami, author Such transcendentalists are everyone and guests spent their time in of The Journey Home, joined us for nonenvious and pure in several areas over the festival site. Kids the entire festival and commented, "No heart.” visited Krishna Land, would-be chefs celebration of Janmastami in the world tested their culinary skills in Veggie compares with Bhaktivedanta Manor's." SB.