Special Issue: the Drucker Centennial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Detailed Resume

William B. Davis, Jr. Windsor Heights, IA (515) 360-0445 linkedin.com/in/billdavisjr [email protected] SOFTWARE & WEB DEVELOPER Accomplished IT professional with extensive experience in all facets of software development lifecycle, user training, and support. Skilled at documentation and user interface design. Always interested in examining new technologies while keeping focus on long-term system planning and maintainability. TECHNICAL SKILLS ● Computers: PCs (Windows, Mac, other), minicomputers (DEC/HP VAX and Alpha), and mainframe (IBM 3090). ● Web technologies: HTML, CSS, Java Server Pages, ASP, and ASP.NET. ● Languages: Java & JSP, JavaScript, Visual BASIC 6 & VBA, VMS BASIC, Microsoft BASIC, Microsoft C, Lattice C, Perl, SQL, COBOL, Pascal, Ruby / Rails, various Assembly languages. ● Scripting: VMS DCL, IBM JCL, Microsoft VBA and VBScript, Unix bash, Windows/DOS batch scripting. ● Operating Systems: Windows, Mac OS & OS X, DEC/HP OpenVMS, Unix, AIX, Linux, other. ● Integrated Development Environments (IDEs): Eclipse, IBM RAD 6, ISPF & Panvalet, Visual -

Service Description IBM Kenexa Talent Acquisition This Service Description Describes the Cloud Service IBM Provides to Client

Service Description IBM Kenexa Talent Acquisition This Service Description describes the Cloud Service IBM provides to Client. Client means the company and its authorized users and recipients of the Cloud Service. The applicable Quotation and Proof of Entitlement (PoE) are provided as separate Transaction Documents 1. IBM Kenexa BrassRing on Cloud The IBM Kenexa Talent BrassRing on Cloud SaaS offering is made up of the following components: a. IBM Kenexa BrassRing on Cloud b. IBM Kenexa BrassRing on Cloud is a scalable, online tool that helps employers and recruiters centralize and manage the Talent Acquisition process across multiple company divisions or locations. Base offering features include: ● Creating and posting job requisitions ● Sourcing ● Talent Gateways for candidates to search jobs and submit interest ● Tracking applications and work flow ● Screening candidates ● Approval levels to facilitate the selection processes ● Standard and ad-hoc reporting capabilities ● Social media interfaces and mobile technology c. The IBM Kenexa BrassRing on Cloud will be provided in both a staging and production environments. The staging environment will be provided through the life of the contract for testing purposes. d. The IBM Kenexa BrassRing on Cloud Onboard can be branded to Client’s company logo and colors. 2. IBM Kenexa Talent Acquisition BrassRing Onboard The IBM Kenexa Talent Acquisition BrassRing Onboard SaaS offering is made up of the following components: a. IBM Kenexa BrassRing on Cloud IBM Kenexa BrassRing on Cloud is a scalable, online tool that helps employers and recruiters centralize and manage the Talent Acquisition process across multiple company divisions or locations. Base offering features include: ● Creating and posting job requisitions ● Sourcing ● Talent Gateways for candidates to search jobs and submit interest ● Tracking applications and work flow ● Screening candidates ● Approval levels to facilitate the selection processes ● Standard and ad-hoc reporting capabilities ● Social media interfaces and mobile technology b. -

Clarion Alumni July 2001

Volume 48 No. 2 July 2001 Clarion University of Pennsylvania Alumni News Surrogate Parenting... Animal Refuge Style -See Page 15- Clarion Grads Lighting a Fire at Scholarship Auction Raises $55,000 Zippo -See Page 8- -See Page 9- Alumni Association Announces Recipients of ‘Distinguished Awards’ See Pages 6 & 7 www.clarion.edu/news 2-CLARION ALUMNI NEWS A L U M N I A S S O C I A T I O N CLARION ALUMNI NEWS Clarion Alumni News is published Stay in Touch three times a year by the Clarion University Alumni Association and remember the day I earned my undergraduate the Office of University Relations. degrees. It was in December of 1997 and even then Tippin Send comments to: University Iwas hot. The speakers were inspirational, my Relations Department, Clarion friends and family were there to cheer and I had an University, 974 E. Wood St., Clarion, PA 16214-1232; 814-393-2334; FAX overwhelming feeling of accomplishment. I 814-393-2082; or e-mail remember sitting in the gym next to my good [email protected]. friend Jen Founds and other communication majors, the people I had been in classes with for ALUMNI ASSOCIATION Alumni Events Calendar four years. It was an incredible day, the day that BOARD OF DIRECTORS you think about from the time you’re in junior Larry W. Jamison ’87,President Saturday, July 28 - Saturday, September 2001 high school. This was the payoff for all my hard John R. Mumford ’73 &’75, Pres.-elect August 4 Saturday, September 8 Wendy A. Clayton, ’85, secretary State System of Higher Alpha Sigma Alpha Gamma work. -

Software Withdrawal and Service Discontinuance: IBM Middleware, IBM Security, IBM Analytics, IBM Storage Software, and IBM Z

IBM United States Withdrawal Announcement 916-117, dated September 13, 2016 Software withdrawal and service discontinuance: IBM Middleware, IBM Security, IBM Analytics, IBM Storage Software, and IBM z Systems select products - Some replacements available Table of contents 1 Overview 107Replacement program information 10 Withdrawn programs 210Corrections Overview Effective on the dates shown, IBM(R) will withdraw support for the following program's VRM licensed under the IBM International Program License Agreement: VRM (V3.2.1) Note: V= All means all versions Note: V#.x means all releases of the version # listed Note: V#.#.x means all mods of the version release # listed For Advanced Administration System (AAS) Systems products Program number Program release VRM Withdrawal from name support date 5608-W07 IBM Tivoli(R) 3.2.x September 30, Storage 2017 (See Note FlashCopy(R) SUPT below) Manager For Passport Advantage(R) (PPA) On Premises products IBM Analytics products Program number Program release VRM Withdrawal from name support date 5639-I80 IBM Content 2.3.x September 30, Manager 2018 ImagePlus(R) Workstation program 5722-VI1 IBM DB2(R) 5.3.x September 30, Content Manager 2018 for iSeries 5724-B35 IBM InfoSphere(R) 5.5.x September 30, OptimTM 2016 Application Repository Analyzer 5724-B35 IBM InfoSphere 6.x September 30, Optim Application 2016 Repository Analyzer IBM United States Withdrawal Announcement 916-117 IBM is a registered trademark of International Business Machines Corporation 1 Program number Program release VRM Withdrawal -

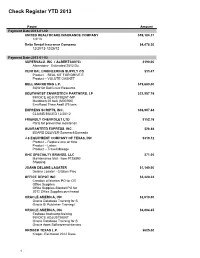

Check Register YTD 2013

Check Register YTD 2013 Payee Amount Payment Date:2013-01-02 UNITED HEALTHCARE INSURANCE COMPANY $59,184.31 1/2/13 Delta Dental Insurance Company $4,478.30 12/20/12-12/26/12 Payment Date:2013-01-03 SUPERVALU, INC ( ALBERTSON'S) $190.00 Alberstons- Estimated 2012 Du CENTRAL ENGINEERING SUPPLY CO $33.47 Product – SEAL KIT FOR DRIVE E Product – VOLUTE GASKET DELL MARKETING L.P. $19,680.00 SOW for Dell Linux Resource SOUTHWEST ENVIROTECH PARTNERS, LP $22,557.74 INVOICE ADJUSTMENT-MP Meltdown 20 bulk (M00756) EnviRoad Thaw Asalt (75 tons, EXPRESS SCRIPTS, INC. $36,907.44 CLAIMS BILLED 12/20/12 FRIENDLY CHEVROLET LTD $152.76 Parts for preventive maintenan GUARANTEED EXPRESS, INC. $26.88 BOARD DELIVER-Summer&Quesada J-8 EQUIPMENT COMPANY OF TEXAS, INC $319.12 Product – Replace one air flow Product – Labor: Product – Travel Mileage GHC SPECIALTY BRANDS, LLC $71.05 Maintenance Mat - Item #125890 Shipping JOANN DELANE LASATER $1,140.00 Delane Lasater - Citation Proc OFFICE DEPOT INC $2,420.24 Creation of blanket PO for Off Office Supplies Office Supplies-Blanket PO for 2012 Office Supplies purchased ORACLE AMERICA, INC $2,010.00 Oracle Database Training for S Oracle BI Publisher Training f ORACLE AMERICA, INC $6,004.45 Essbase bootcamp training INVOICE ADJUSTMENT Oracle Database Training for S Oracle Apps Softwaremaintenanc KROGER TEXAS L.P. $625.00 Kroger- Estimated 2012 Dues 1 Payee Amount DAVID L. MCNATT $284.93 DISCOUNT 10% NET 15 David McNatt - Citation Proces eVERGE GROUP OF TEXAS LTD. $5,960.00 2012 PS Maintenance & Support PeopleSoft Consulting services INTEGRATED ACCESS SYSTEMS $5,611.92 2013 security system maintenan ZENISYS CORPORATION $238,710.00 ARM Support SCIP Maint and Support V for RITE Upgrade EVCO PARTNERS, LP dba BURGOON COMPANY $2,588.36 Maintenance Supplies Product – Professional Mechani METROPLEX BATTERY INC. -

IBM ® Kenexa ® Skills Assessments on Cloud Validation and Reliability

® ® IBM Kenexa Skills Assessments on Cloud Validation and Reliability © 2018 IBM 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SKILLS TESTING .......................................................................................................... 3 TEST FORMAT .......................................................................................................................... 3 Test Components .................................................................................................................................. 3 LENGTH OF TIME TO COMPLETE AN ASSESSMENT .............................................................................. 4 CUSTOMER GUIDELINES .............................................................................................. 5 CUSTOMER RESPONSIBILITY ....................................................................................................... 5 Customer Compliance ............................................................................................................................ 5 Picking the Right Assessment .................................................................................................................. 5 Implementation ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Scoring Guidelines ................................................................................................................................. 7 Cut Scores ........................................................................................................................................... -

Sejarah Perkembangan Dan Kemajuan the International Bussines Machines

SEJARAH PERKEMBANGAN DAN KEMAJUAN THE INTERNATIONAL BUSSINES MACHINES Oleh : ANGGARA WISNU PUTRA 1211011018 CIPTA AJENG PRATIWI 1211011034 DERI KURNIAWAN 1211011040 FEBY GIPANTIUS ZAMA 1211011062 NOVITA LIANA SARI 1211011118 RAMA AGUSTINA 1211011128 FAKULTAS EKONOMI DAN BISNIS UNIVERSITAS LAMPUNG BANDAR LAMPUNG 2014 BAB II PEMBAHASAN 2.1 Sejarah berdirinya THE INTERNATIONAL BUSSINES MACHINES (IBM) 1880—1929 Pada tahun 1880-an, beberapa teknologi yang akan menjadi bisnis IBM ditemukan. Julius E. Pitrap menemukan timbangan komputer pada tahun 1885. Alexander Dey menemukan dial recorder tahun 1888. Herman Hollerith menemukan Electric Tabulating Machine 1989 dan pada tahun yang sama Williard Bundy menemukan alat untuk mengukur waktu kerja karyawan. Pada 16 Juni 1911, teknologi-teknologi tersebut dan perusahaan yang memilikinya digabungkan oleh Charles Ranlett Flint dan membentuk Computing Tabulating Recording Company (CTR). Perusahaan yang berbasis di New York ini memiliki 1.300 karyawan dan area perkantoran serta pabrik di Endicott dan Binghamton, New York; Dayton, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; Washington, D.C.; dan Toronto, Ontario. CTR memproduksi dan menjual berbagai macam jenis mesin mulai dari timbangan komersial hingga pengukur waktu kerja. Pada tahun 1914, Flint merekrut Thomas J. Watson, Sr., dari National Cash Register Company, untuk membantunya memimpin perusahaan. Watson menciptakan slogan, ―THINK‖, yang segera menjadi mantra bagi karyawan CTR. Dalam waktu 11 bulan setelah bergabung, Watson menjadi presiden dari CTR. Perusahaan memfokuskan diri pada penyediaan solusi penghitungan dalam skala besar untuk bisnis. Selama empat tahun pertama kepemimpinannya, Watson sukses meningkatkan pendapatan hingga lebih dari dua kali lipat dan mencapai $9 juta. Ia juga sukses mengembangkan sayap ke Eropa, Amerika Selatan, Asia, dan Australia. Pada 14 Februari 1924, CTR berganti nama menjadi International Business Machines Corporation (IBM). -

IBM Kenexa Assessments Solutions Brief and Catalog

IBM Kenexa Solutions Brief and Catalog IBM Kenexa Assessments Solutions Brief and Catalog Choosing the right person for the right job, and assessing traits, skills and fit for individuals, managers, and leaders is crucial to your success. IBM Kenexa Assessments Catalog IBM Kenexa offers an expansive portfolio of assessments • A multiple-choice format and newer formats of that assess personality traits, problem solving, learned skills, simulation and computer-adaptive testing for job and job/organizational fit. Our assessments are designed for evaluation. all levels of an organization, including individual • Capacity and capability assessments including natural contributors, managers, and leaders. IBM Kenexa Assess on talent in a specific area, work style preferences, acquired Cloud is one of the industry’s largest and most powerful experience, and a combination of cognition and global and mobile capable content solutions available in the knowledge; organizational fit assessments that measure marketplace today. IBM Kenexa Assessments provide you fit in terms of company culture, values, and preferences with industry-leading content and support to find quality for job characteristics; and onboarding assessments to candidates and maximize their performance. help accelerate time-to-productivity of new hires and understand their learning styles. At IBM Kenexa, we know that people differentiate great • Each result includes a detailed candidate profile that companies. We believe empowering companies to hire the reveals strengths and developmental needs as compared right people yields the best business results. IBM Kenexa to the job evaluation; follow-up interview questions employs Ph.D. or licensed Industrial/Organizational (I/O) tailored to the role and the candidate’s specific results; psychologists worldwide. -

USEF) Intermediaire I Dressage National Championship and Yang Showing Garden’S Sam in the USEF Children Dressage

USET Foundation PHILANTHROPIC PARTNER OF US EQUESTRIAN NEWS VOLUME 18, ISSUE 3 • FALL 2019 THE 2020 TOKYO OLYMPIC GAMES WILL BRING AKIKO YAMAZAKI FULL CIRCLE The ardent supporter of U.S. Dressage is looking forward to seeing her passion merge with her heritage. BY MOLLY SORGE Attending the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games will be an emotional experience for Akiko Yamazaki – and not only because she hopes her horse, Suppenkasper, will be named to the U.S. Dressage Team with rider Steffen Peters. When Yamazaki sits down in the stands at Equestrian Park at Baji Koen, she’ll be sitting next to her mother, Michiko, who is the person who inspired her love of horses, and her two daughters, who share their passion for riding. My mom attended the Tokyo Olympic Games in 1964 as a spectator,” Yamazaki said. “Now we’ll go to watch the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games at the“ same venue, and hopefully we’ll be watching one of our horses compete. My mother is going to be 79 years old, and she’s really looking forward to going back and watching the Games in Tokyo. We are three generations of riders. It’s coming full circle.” For Yamazaki, who sits on the Board of Trustees and serves as the Secretary of the U.S. Equestrian Team (USET) Foundation, that feeling of legacy is a big part of why she loves equestrian sport so much. Her mother introduced her to riding when she was young, and now Yamazaki’s daughters have not only grown up immersed in the sport but have also developed their own passion for riding. -

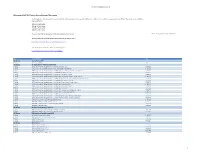

IBM Services ISMS / PIMS Products / Pids in Scope

1H 2021 Certified Product List IBM services ISMS/PIMS Product/Service Offerings/PIDs in scope The following is a list of products associated with the offering bundles in scope of the IBM services information security management system (ISMS). The Cloud services ISMS has been certified on: ISO/IEC 27001:2013 ISO/IEC 27017:2015 ISO/IEC 27018:2019 ISO/IEC 27701:2019 As well as the IBM Cloud Services STAR Self-Assessment found here: This listing is current as of 07/20/2021 IBM Cloud Services STAR Self-Assessment Cloud Controls Matrix v3.0.1 https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/registry/ibm-cloud/ To find out more about IBM Cloud compliance go to: https://www.ibm.com/cloud/compliance/global type groupNameproductName pids ISO Group AccessHub-at-IBM Offering AccessHub-at-IBM N/A ISO Group AI Applications - Maximo and TRIRIGA Offering IBM Enterprise Asset Management Anywhere on Cloud (Maximo) 5725-Z55 Offering IBM Enterprise Asset Management Anywhere on Cloud (Maximo) Add-On 5725-Z55 Offering IBM Enterprise Asset Management on Cloud (Maximo) Asset Configuration Manager Add-On 5725-P73 Offering IBM Enterprise Asset Management on Cloud (Maximo) Aviation Add-On 5725-P73 Offering IBM Enterprise Asset Management on Cloud (Maximo) Calibration Add-On 5725-P73 Offering IBM Enterprise Asset Management on Cloud (Maximo) for Managed Service Provider Add-On 5725-P73 Offering IBM Enterprise Asset Management on Cloud (Maximo) Health, Safety and Environment Manager Add-On 5725-P73 Offering IBM Enterprise Asset Management on Cloud (Maximo) Life Sciences Add-On -

Hire with Confidence IBM Kenexa Employee Assessments Full Product Catalog

Hire with confidence IBM Kenexa Employee Assessments Full product catalog IBM Kenexa Employee Assessments Catalog 1 Businesses that use pre-hire assessments are 36% more likely than all others to be satisfied with their new hires. Pre-Hire Assessments: An Asset for HR in the Age of the Candidate, Zach Lahey, Aberdeen 2015 IBM® Kenexa® Employee Assessments use 1,200+ behavioral science techniques to measure traits, off-the-shelf mobile skills, and fit of candidates and/or employees. responsive assessments A team of I/O psychologists and 30+ years of behavioral science expertise have ensured the portfolio – which can easily complement your 44+ existing assessments solutions – includes, but is languages not limited to: • Job evaluation tools to help predict executive 30 million+ performance • Functional behavior assessments to find the assessments administered best fit for hourly employees annually • Skills assessments help you sift through talent pools • Proven, valid, and legally defensible 30+ years assessments of behavioral science expertise backed by I/O psychologists Start your free trial today Get in touch to discuss the right assessment solution for your business t IBM Kenexa Employee Assessments Catalog 2 Assess the whole person to predict fit and performance. Click the labels below to see details. What kind of job are you trying to fill? Accounting/ Call Center/ Administrative Cybersecurity Healthcare Hospitality Finance Customer Service Industrial/ IT/Technical Legal Management Retail Sales Warehouse Software Learn more about the types of insights we provide Behavior & Abilities Fit Skills Specialty Offerings Personality Learn more about our test experience options Computer Data Entry Fill-in-the-blank Fit Likert Multiple Choice Adaptive Open Response Proofreading Simulation Spelling Typing Are you a staffing agency? We have solutions for you. -

Jim Mcnerney

Biography The Boeing Company 100 N. Riverside Plaza, MC 5003-5495 Chicago, IL 60606 www.boeing.com W. JAMES MCNERNEY, JR. Chairman and Chief Executive Officer The Boeing Company W. James (Jim) McNerney, Jr., is chairman of the board and chief executive officer of The Boeing Company. McNerney, 64, oversees the strategic direction of the Chicago-based, $86.6 billion aerospace company. With more than 168,000 employees across the United States and in more than 65 countries, Boeing is the world's largest aerospace company and a top U.S. exporter. It is the leading manufacturer of commercial airplanes, military aircraft, and defense, space and security systems; it supports airlines and U.S. and allied government customers in more than 150 nations. McNerney joined Boeing as chairman, president and CEO on July 1, 2005. Before that, he served as chairman of the board and CEO of 3M, then a $20 billion global technology company with leading positions in electronics, telecommunications, industrial, consumer and office products, health care, safety and other businesses. He joined 3M in 2000 after 19 years at the General Electric Company. McNerney joined General Electric in 1982. There, he held top executive positions including president and CEO of GE Aircraft Engines and GE Lighting; president of GE Asia-Pacific; president and CEO of GE Electrical Distribution and Control; executive vice president of GE Capital, one of the world's largest financial service companies; and president, GE Information Services. Prior to joining GE, McNerney worked at Procter & Gamble and McKinsey & Co., Inc. By appointment of U.S.