Energy Landscapes for the Self-Assembly of Supramolecular Polyhedra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symmetry of Fulleroids Stanislav Jendrol’, František Kardoš

Symmetry of Fulleroids Stanislav Jendrol’, František Kardoš To cite this version: Stanislav Jendrol’, František Kardoš. Symmetry of Fulleroids. Klaus D. Sattler. Handbook of Nanophysics: Clusters and Fullerenes, CRC Press, pp.28-1 - 28-13, 2010, 9781420075557. hal- 00966781 HAL Id: hal-00966781 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00966781 Submitted on 27 Mar 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Symmetry of Fulleroids Stanislav Jendrol’ and Frantiˇsek Kardoˇs Institute of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, P. J. Saf´arikˇ University, Koˇsice Jesenn´a5, 041 54 Koˇsice, Slovakia +421 908 175 621; +421 904 321 185 [email protected]; [email protected] Contents 1 Symmetry of Fulleroids 2 1.1 Convexpolyhedraandplanargraphs . .... 3 1.2 Polyhedral symmetries and graph automorphisms . ........ 4 1.3 Pointsymmetrygroups. 5 1.4 Localrestrictions ............................... .. 10 1.5 Symmetryoffullerenes . .. 11 1.6 Icosahedralfulleroids . .... 12 1.7 Subgroups of Ih ................................. 15 1.8 Fulleroids with multi-pentagonal faces . ......... 16 1.9 Fulleroids with octahedral, prismatic, or pyramidal symmetry ........ 19 1.10 (5, 7)-fulleroids .................................. 20 1 Chapter 1 Symmetry of Fulleroids One of the important features of the structure of molecules is the presence of symmetry elements. -

Origin of Icosahedral Symmetry in Viruses

Origin of icosahedral symmetry in viruses Roya Zandi†‡, David Reguera†, Robijn F. Bruinsma§, William M. Gelbart†, and Joseph Rudnick§ Departments of †Chemistry and Biochemistry and §Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1569 Communicated by Howard Reiss, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, August 11, 2004 (received for review February 2, 2004) With few exceptions, the shells (capsids) of sphere-like viruses (11). This problem is in turn related to one posed much earlier have the symmetry of an icosahedron and are composed of coat by Thomson (12), involving the optimal distribution of N proteins (subunits) assembled in special motifs, the T-number mutually repelling points on the surface of a sphere, and to the structures. Although the synthesis of artificial protein cages is a subsequently posed ‘‘covering’’ problem, where one deter- rapidly developing area of materials science, the design criteria for mines the arrangement of N overlapping disks of minimum self-assembled shells that can reproduce the remarkable properties diameter that allow complete coverage of the sphere surface of viral capsids are only beginning to be understood. We present (13). In a similar spirit, a self-assembly phase diagram has been here a minimal model for equilibrium capsid structure, introducing formulated for adhering hard disks (14). These models, which an explicit interaction between protein multimers (capsomers). all deal with identical capsomers, regularly produced capsid Using Monte Carlo simulation we show that the model reproduces symmetries lower than icosahedral. On the other hand, theo- the main structures of viruses in vivo (T-number icosahedra) and retical studies of viral assembly that assume icosahedral sym- important nonicosahedral structures (with octahedral and cubic metry are able to reproduce the CK motifs (15), and, most symmetry) observed in vitro. -

Archimedean Solids

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln MAT Exam Expository Papers Math in the Middle Institute Partnership 7-2008 Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Anderson, Anna, "Archimedean Solids" (2008). MAT Exam Expository Papers. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Math in the Middle Institute Partnership at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAT Exam Expository Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Teaching with a Specialization in the Teaching of Middle Level Mathematics in the Department of Mathematics. Jim Lewis, Advisor July 2008 2 Archimedean Solids A polygon is a simple, closed, planar figure with sides formed by joining line segments, where each line segment intersects exactly two others. If all of the sides have the same length and all of the angles are congruent, the polygon is called regular. The sum of the angles of a regular polygon with n sides, where n is 3 or more, is 180° x (n – 2) degrees. If a regular polygon were connected with other regular polygons in three dimensional space, a polyhedron could be created. In geometry, a polyhedron is a three- dimensional solid which consists of a collection of polygons joined at their edges. The word polyhedron is derived from the Greek word poly (many) and the Indo-European term hedron (seat). -

The Cubic Groups

The Cubic Groups Baccalaureate Thesis in Electrical Engineering Author: Supervisor: Sana Zunic Dr. Wolfgang Herfort 0627758 Vienna University of Technology May 13, 2010 Contents 1 Concepts from Algebra 4 1.1 Groups . 4 1.2 Subgroups . 4 1.3 Actions . 5 2 Concepts from Crystallography 6 2.1 Space Groups and their Classification . 6 2.2 Motions in R3 ............................. 8 2.3 Cubic Lattices . 9 2.4 Space Groups with a Cubic Lattice . 10 3 The Octahedral Symmetry Groups 11 3.1 The Elements of O and Oh ..................... 11 3.2 A Presentation of Oh ......................... 14 3.3 The Subgroups of Oh ......................... 14 2 Abstract After introducing basics from (mathematical) crystallography we turn to the description of the octahedral symmetry groups { the symmetry group(s) of a cube. Preface The intention of this account is to provide a description of the octahedral sym- metry groups { symmetry group(s) of the cube. We first give the basic idea (without proofs) of mathematical crystallography, namely that the 219 space groups correspond to the 7 crystal systems. After this we come to describing cubic lattices { such ones that are built from \cubic cells". Finally, among the cubic lattices, we discuss briefly the ones on which O and Oh act. After this we provide lists of the elements and the subgroups of Oh. A presentation of Oh in terms of generators and relations { using the Dynkin diagram B3 is also given. It is our hope that this account is accessible to both { the mathematician and the engineer. The picture on the title page reflects Ha¨uy'sidea of crystal structure [4]. -

Systematics of Atomic Orbital Hybridization of Coordination Polyhedra: Role of F Orbitals

molecules Article Systematics of Atomic Orbital Hybridization of Coordination Polyhedra: Role of f Orbitals R. Bruce King Department of Chemistry, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] Academic Editor: Vito Lippolis Received: 4 June 2020; Accepted: 29 June 2020; Published: 8 July 2020 Abstract: The combination of atomic orbitals to form hybrid orbitals of special symmetries can be related to the individual orbital polynomials. Using this approach, 8-orbital cubic hybridization can be shown to be sp3d3f requiring an f orbital, and 12-orbital hexagonal prismatic hybridization can be shown to be sp3d5f2g requiring a g orbital. The twists to convert a cube to a square antiprism and a hexagonal prism to a hexagonal antiprism eliminate the need for the highest nodality orbitals in the resulting hybrids. A trigonal twist of an Oh octahedron into a D3h trigonal prism can involve a gradual change of the pair of d orbitals in the corresponding sp3d2 hybrids. A similar trigonal twist of an Oh cuboctahedron into a D3h anticuboctahedron can likewise involve a gradual change in the three f orbitals in the corresponding sp3d5f3 hybrids. Keywords: coordination polyhedra; hybridization; atomic orbitals; f-block elements 1. Introduction In a series of papers in the 1990s, the author focused on the most favorable coordination polyhedra for sp3dn hybrids, such as those found in transition metal complexes. Such studies included an investigation of distortions from ideal symmetries in relatively symmetrical systems with molecular orbital degeneracies [1] In the ensuing quarter century, interest in actinide chemistry has generated an increasing interest in the involvement of f orbitals in coordination chemistry [2–7]. -

Can Every Face of a Polyhedron Have Many Sides ?

Can Every Face of a Polyhedron Have Many Sides ? Branko Grünbaum Dedicated to Joe Malkevitch, an old friend and colleague, who was always partial to polyhedra Abstract. The simple question of the title has many different answers, depending on the kinds of faces we are willing to consider, on the types of polyhedra we admit, and on the symmetries we require. Known results and open problems about this topic are presented. The main classes of objects considered here are the following, listed in increasing generality: Faces: convex n-gons, starshaped n-gons, simple n-gons –– for n ≥ 3. Polyhedra (in Euclidean 3-dimensional space): convex polyhedra, starshaped polyhedra, acoptic polyhedra, polyhedra with selfintersections. Symmetry properties of polyhedra P: Isohedron –– all faces of P in one orbit under the group of symmetries of P; monohedron –– all faces of P are mutually congru- ent; ekahedron –– all faces have of P the same number of sides (eka –– Sanskrit for "one"). If the number of sides is k, we shall use (k)-isohedron, (k)-monohedron, and (k)- ekahedron, as appropriate. We shall first describe the results that either can be found in the literature, or ob- tained by slight modifications of these. Then we shall show how two systematic ap- proaches can be used to obtain results that are better –– although in some cases less visu- ally attractive than the old ones. There are many possible combinations of these classes of faces, polyhedra and symmetries, but considerable reductions in their number are possible; we start with one of these, which is well known even if it is hard to give specific references for precisely the assertion of Theorem 1. -

On Polyhedra with Transitivity Properties

Discrete Comput Geom 1:195-199 (1986) iSCrete & Computathm~ ~) 1986 Springer-V©rlagometrvNew York Inc. IF On Polyhedra with Transitivity Properties J. M. Wills Mathematics Institute, University of Siegen, Hoelderlinstrasse 3, D-5900 Siegen, FRG Abstract. In a remarkable paper [4] Griinbaum and Shephard stated that there is no polyhedron of genus g > 0, such that its symmetry group acts transitively on its faces. If this condition is slightly weakened, one obtains" some interesting polyhedra with face-transitivity (resp. vertex-transitivity). In recent years several attempts have been/made to find polyhedral analogues for the Platonic solids in the Euclidean 3-space E 3 (cf. [1, 4, 5, 7-14]). By a polyhedron P we mean the union of a finite number of plane polygons in E 3 which form a 2-manifold without boundary and without self-intersections, where, as usual, a plane polygon is a plane set bounded by finitely many line segments. If the plane polygons are disjoint except for their edges, they are called the faces of P. We require adjacent faces to be non-coplanar. The vertices and edges of P are the vertices and edges of the faces of P. The genus of the underlying 2-manifold is the genus of P. A flag of P is a triplet consisting of one vertex, one edge incident with this vertex, and one face containing this edge. If, for given p- 3, q >- 3 all faces of P are p-gons and all vertices q-valent, we say that P is equivelar, i.e., has equal flags (cf. -

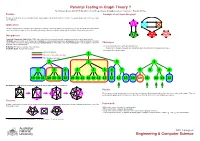

Parental Testing in Graph Theory?

Parental Testing in Graph Theory ? By S Narjess Afzaly,∗ ANU CSIT Algorithm & Data Group, [email protected]. Supervisor: Brendan McKay.∗ Problem A sample of an irreducible graph To make a complete list of non-isomorphic simple quartic graphs with the given number of vertices. In a quartic graph, each vertex has exactly four neighbours. Applications Finding counterexamples, verifying some conjectures or refining some proofs whether in graph theory or in any other field where the problem can be modelled as a graph such as: chemistry, web mining, national security, the railway map, the electrical circuit and neural science. Our approach Canonical Construction Path (McKay 1998): A general method to recursively generate combinatorial objects in which larger objects, (Children), are constructed out of smaller ones, (Parents), by some well-defined operation, (extension), and avoiding constructing isomorphic copies at each construction step by defining a unique genuine parent for each graph. Hence a generated graph is only accepted if it has been Challenges extended from its genuine parent. • To avoid isomorphic copies when generating the list: Reduction: The inverse operation of the extension. Irreducible graph: A graph with no parent. The definition of the genuine parent can substantially affect the efficiency of the generation process. • Generating all irreducible graphs. Genuine parent 1 Has an isomorphic sibling Not genuine parent 2 2 3 4 5 5 6 5 5 6 6 7 5 8 9 6 10 10 11 10 10 11 12 10 10 11 10 10 11 12 12 12 13 10 10 11 10 13 12 Our Reduction: Deleting a vertex and adding two extra disjoint edges between its neighbours. -

Fast Generation of Planar Graphs (Expanded Version)

Fast generation of planar graphs (expanded version) Gunnar Brinkmann∗ Brendan D. McKay† Department of Applied Mathematics Department of Computer Science and Computer Science Australian National University Ghent University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia B-9000 Ghent, Belgium [email protected] [email protected] Abstract The program plantri is the fastest isomorph-free generator of many classes of planar graphs, including triangulations, quadrangulations, and convex polytopes. Many applications in the natural sciences as well as in mathematics have appeared. This paper describes plantri’s principles of operation, the basis for its efficiency, and the recursive algorithms behind many of its capabilities. In addition, we give many counts of isomorphism classes of planar graphs compiled using plantri. These include triangulations, quadrangulations, convex polytopes, several classes of cubic and quartic graphs, and triangulations of disks. This paper is an expanded version of the paper “Fast generation of planar graphs” to appeared in MATCH. The difference is that this version has substantially more tables. 1 Introduction The program plantri can rapidly generate many classes of graphs embedded in the plane. Since it was first made available, plantri has been used as a tool for research of many types. We give only a partial list, beginning with masters theses [37, 40] and PhD theses [32, 42]. Applications have appeared in chemistry [8, 21, 28, 39, 44], in crystallography [19], in physics [25], and in various areas of mathematics [1, 2, 7, 20, 22, 24, 41]. ∗Research supported in part by the Australian National University. †Research supported by the Australian Research Council. 1 The purpose of this paper is to describe the facilities of plantri and to explain in general terms the method of operation. -

Are Your Polyhedra the Same As My Polyhedra?

Are Your Polyhedra the Same as My Polyhedra? Branko Gr¨unbaum 1 Introduction “Polyhedron” means different things to different people. There is very little in common between the meaning of the word in topology and in geometry. But even if we confine attention to geometry of the 3-dimensional Euclidean space – as we shall do from now on – “polyhedron” can mean either a solid (as in “Platonic solids”, convex polyhedron, and other contexts), or a surface (such as the polyhedral models constructed from cardboard using “nets”, which were introduced by Albrecht D¨urer [17] in 1525, or, in a more mod- ern version, by Aleksandrov [1]), or the 1-dimensional complex consisting of points (“vertices”) and line-segments (“edges”) organized in a suitable way into polygons (“faces”) subject to certain restrictions (“skeletal polyhedra”, diagrams of which have been presented first by Luca Pacioli [44] in 1498 and attributed to Leonardo da Vinci). The last alternative is the least usual one – but it is close to what seems to be the most useful approach to the theory of general polyhedra. Indeed, it does not restrict faces to be planar, and it makes possible to retrieve the other characterizations in circumstances in which they reasonably apply: If the faces of a “surface” polyhedron are sim- ple polygons, in most cases the polyhedron is unambiguously determined by the boundary circuits of the faces. And if the polyhedron itself is without selfintersections, then the “solid” can be found from the faces. These reasons, as well as some others, seem to warrant the choice of our approach. -

New Perspectives on Polyhedral Molecules and Their Crystal Structures Santiago Alvarez, Jorge Echeverria

New Perspectives on Polyhedral Molecules and their Crystal Structures Santiago Alvarez, Jorge Echeverria To cite this version: Santiago Alvarez, Jorge Echeverria. New Perspectives on Polyhedral Molecules and their Crystal Structures. Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry, Wiley, 2010, 23 (11), pp.1080. 10.1002/poc.1735. hal-00589441 HAL Id: hal-00589441 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00589441 Submitted on 29 Apr 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry New Perspectives on Polyhedral Molecules and their Crystal Structures For Peer Review Journal: Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry Manuscript ID: POC-09-0305.R1 Wiley - Manuscript type: Research Article Date Submitted by the 06-Apr-2010 Author: Complete List of Authors: Alvarez, Santiago; Universitat de Barcelona, Departament de Quimica Inorganica Echeverria, Jorge; Universitat de Barcelona, Departament de Quimica Inorganica continuous shape measures, stereochemistry, shape maps, Keywords: polyhedranes http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/poc Page 1 of 20 Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 New Perspectives on Polyhedral Molecules and their Crystal Structures 11 12 Santiago Alvarez, Jorge Echeverría 13 14 15 Departament de Química Inorgànica and Institut de Química Teòrica i Computacional, 16 Universitat de Barcelona, Martí i Franquès 1-11, 08028 Barcelona (Spain). -

Smallest Cubic and Quartic Graphs with a Given Number of Cutpoints and Bridges Gary Chartrand

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Mathematics & Statistics Faculty Publications Mathematics & Statistics 1982 Smallest Cubic and Quartic Graphs With a Given Number of Cutpoints and Bridges Gary Chartrand Farrokh Saba John K. Cooper Jr. Frank Harary Curtiss E. Wall Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/mathstat_fac_pubs Part of the Mathematics Commons Repository Citation Chartrand, Gary; Saba, Farrokh; Cooper, John K. Jr.; Harary, Frank; and Wall, Curtiss E., "Smallest Cubic and Quartic Graphs With a Given Number of Cutpoints and Bridges" (1982). Mathematics & Statistics Faculty Publications. 76. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/mathstat_fac_pubs/76 Original Publication Citation Chartrand, G., Saba, F., Cooper, J. K., Harary, F., & Wall, C. E. (1982). Smallest cubic and quartic graphs with a given number of cutpoints and bridges. International Journal of Mathematics and Mathematical Sciences, 5(1), 41-48. doi:10.1155/s0161171282000052 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mathematics & Statistics at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics & Statistics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I nternat. J. Math. & Math. Sci. Vol. 5 No. (1982)41-48 41 SMALLEST CUBIC AND QUARTIC GRAPHS WITH A GIVEN NUMBER OF CUTPOINTS AND BRIDGES GARY CHARTRAND and FARROKH SABA Department of Mathematics, Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan 49008 U. S .A. JOHN K. COOPER, JR. Department of Mathematics, Eastern Michigan University Ypsilanti, Michigan 48197 U.S.A. FRANK HARARY Department of Mathematics, University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104 U.S.A.