Remembering Dian Fossey: Primatology, Celebrity, Mythography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 1 Module A: Jane Goodall Biography

Grade 4 Informative Writing Prompt District Common Writing Assessment Unit 1 Module A: Jane Goodall Biography Directions should be read aloud and clarified by the teacher. Directions Today, you are going to get ready to write a biography about Jane Goodall and how she made a difference in the world as a scientist. You are going to use what you have learned to write a biography which addresses the question: How did Jane Goodall make a difference in the world as a scientist? Day 1 Get ready to write. • Watch the video, Jane Goodall Mini Biography. (Link attached below) • Discuss how Jane Goodall made a difference in the world as a scientist. • Listen to and read the article: "Biographies for Kids: Jane Goodall". (Attached) You may want to take notes for your biography as you read. • Why was Jane Goodall an important scientist? Turn and talk to a partner about what you read in the text and heard in the video. Teacher notes: Take this time to use whatever note taking and partnering strategies you have been using in class. The video has a commercial at the start so please cue before viewing. Days 2-3 Write! • Watch the video, Jane Goodall Mini Biography. (Link attached below) • Listen to and read the article: "Biographies for Kids: Jane Goodall" (Attached) • When you have finished, write a biography detailing Jane Goodall’s life and how she made a difference in the world as a scientist. Remember, a good biography / informative essay: • Has an introduction • Clearly introduces the subject • Develops a main idea about the subject with facts and concrete details • Groups ideas in paragraphs • Uses precise language and vocabulary • Uses linking words to connect ideas • Has correct spelling, capitalization, and punctuation • Uses quotes to cite sources • Has an effective concluding statement Resources: Article: "Biographies for Kids Jane Goodall" (Attached) Video: Jane Goodall Mini Biography. -

Tropical Malady: Film & the Question of the Uncanny Human-Animal

etropic 10(2011): Creed, Tropical Malady | 131 Tropical Malady: Film & the Question of the Uncanny Human-Animal “The tiger trails you like a shadow/ his spirit is starving and lonesome/I see you are his prey and his companion” – Tropical Malady. Barbara Creed University of Melbourne Abstract The acclaimed Thai film, Tropical Malady (2004), represents the tropics as a surreal place where conscious and unconscious are as inextricably entwined. Directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Tropical Malady presents two interconnected stories: one a quirky gay love story; the other a strange disconnected narrative about a shape-shifting shaman, a man-beast and a ghostly tiger. This paper will argue that from it beginnings in the silent period, the cinema has created an uncanny zone of tropicality where human and animal merge. rom its beginnings in the early twentieth century the cinema has expressed an F enduring fascination with the tropics as an imaginary space. While many filmmakers have envisaged the tropics as an unspoiled paradise (Bird of Paradise, 1932, 1951; The Moon of Manakoora, 1943; South Pacific, 1958), a view which has its origins in classical times, others have represented the tropics as a deeply uncanny zone where familiar and unfamiliar coalesce. It is as if the heat and intensity of the tropics has liquefied matter until normally incommensurate forms are able to dissolve almost imperceptibly into each other. In this process the boundaries between different systems of thought, ideas and ethics similarly dissipate, creating a space for new and often subversive ideas to flourish. As Driver and Martins state, the meaning of “tropicality” is so elastic a number of discourses have been able to shape it to suit their own purposes. -

Tv Pg 5 04-04.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, April 4, 2008 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle FUN BY THE NUM B ERS will have you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, column and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO TUESD A Y ’S SATURDAY EVENING APRIL 5, 2008 SUNDAY EVENING APRIL 6, 2008 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone The First 48: Stray Bullet; The First 48 Body rolled in The Sopranos (TVMA) (:18) The First 48 (TVPG) (:18) The First 48: Stray Bul- “The Godfather” (‘72, Drama) A decorated veteran takes over control of his family’s criminal empire from “The Godfather” (‘72) Ma- 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E his ailing father as new threats and old enemies conspire to destroy them. (R) fia family life. -

Congressional Record—Senate S10810

S10810 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE December 20, 2010 advocate for the Peace Corps program food safety dangers occur and are oc- Senior citizens deserve to have hous- and for volunteerism in general. In curring. The use of indirect food addi- ing that will help them maintain their that regard, he and I have much in tives and processing aids have not been independence. It is my hope that with common. As a young man, I served a determined to be the source of food the passage of S. 118, many more Amer- full-time mission for the Church of borne illness outbreaks and I believe it icans have a place to call home during Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I too is important that the FDA continue to their golden years. learned much about the benefits of focus its scarce resources on the key f selfless, volunteer service while serving elements that this legislation hopes to TRIBUTE TO DR. JANE GOODALL as a missionary and those 2 years were address in the Food Safety area. instrumental in my understanding of f Mr. UDALL of New Mexico. Mr. the world and instilled me with a de- President, in July I introduced S. Res. ELDERLY HOUSING sire to serve and help others. The Serve 581, a resolution honoring the edu- America Act was meant to embody Mr. KOHL. Mr. President, I rise cational and scientific significance of these ideals and provide similar oppor- today to praise the passage of S. 118, Dr. Jane Goodall on the 50th anniver- tunities for others. It could have very the section 202 Supportive Housing for sary of the beginning of her work in easily been a purely Democratic en- the Elderly Act. -

An Eye to the Future Advances in Imaging Are Accelerating the Pace of Biological Discovery

fall 2007 An Eye to the Future Advances in imaging are accelerating the pace of biological discovery. A new cellular imaging initiative at the University has researchers seeing small and thinking big. story on page 8 p r o f i l e s college News c l a s s N o t e s from the dean Where curiosity- and solution- driven science meet ome scientists are driven by a curiosity to under- As a curiosity-driven college, it’s CBS’ job to keep S stand how life works—from molecules to eco- adding to the foundation of knowledge that supports systems—and to add to the world’s collective body of translational and solution-driven science in other col- knowledge. Others are searching for a puzzle piece leges. As such, we are the stewards of the foundational that may yield a better way to treat cancer, produce disciplines in the biological sciences: biochemistry, food or create renewable forms of energy. molecular biology, genetics, cell biology and develop- ment, ecology, plant biology, etc. Both are essential, and there is plenty of overlap Robert Elde, Dean between the two. Curiosity-driven research often turns In order to keep fueling translational and solution- up a bit of information that has immediate applications driven research, we need to infuse foundational disci- in medicine, agriculture or engineering. By the same plines with new technologies and other opportunities token, solution-driven research can add to knowledge. as science evolves. And some scientists travel between these two worlds. Fall 07 Vol. 5 No. 3 Cellular imaging, the subject of our cover story, is one As a whole, College of Biological Sciences faculty of those opportunities. -

Inspiring Spaces

FALL 2011 Inspiring Spaces Explorations Grand Challenges and Inspiration: Lighting the Fire in the Next Generation 2011 Bradford Washburn Award In Gratitude Raytheon: Our Newest Premier Partner Fiscal Year 2011 Annual Report 418496 Booklet.CS4.indd 3 11/22/11 5:49 AM FIELD NOTES contents Special Nights with Special Friends… Nothing gets the Museum’s community of friends and supporters energized like a special event, and we were fortunate to have more than a few fantastic evening events this fall. A Day in Pompeii (see IN BRIEF) gave us an opportunity to gather and experience the art and archaeological artifacts of the ancient world, and two of our annual award programs offered us a chance to celebrate those members of the Museum community who inspire us most. We presented the 47th Bradford Washburn Award to Jean-Michel Cousteau on September 7 (see pages 22 – 23 for story and photos). In addition to recognizing Cousteau’s commitment to ocean exploration and environmental protection, the Washburn Award dinner provides us the occasion every year to remember Brad Washburn, the visionary founding director of the Museum of Science. On November 3 we honored members of the Colby Society, donors whose cumulative giving to the Museum is in excess of $100,000 (page 39). At the Colby dinner we paid special tribute to Sophia and Bernie Gordon, whose remarkable philanthropy is felt in the Museum every day at the Gordon Current Science & Technology Center, which was established in 2006 with their lead gift. The Gordons were presented with the Colonel Francis T. Colby Award and their names will join our inaugural Colby honorees, trustee emeriti Joan Suit and Brit d’Arbeloff, on the plaque beside the elephant doors at the entrance to the Museum’s Colby Room (see pages 18 – 19 for story and photos). -

Final Report on the Grasp-Ian Redmond Conservation Award

FINAL REPORT ON THE GRASP-IAN REDMOND CONSERVATION AWARD Grant about “increasing local awareness about the importance of preserving chimpanzees of the Gishwati-Mukura National Park, Rwanda”. Supported by February 2020 FINAL REPORT ON THE GRANT IMPLEMENTATION 1. Introduction In 2019 January, Forest of Hope Association (FHA) started the implementation of the GRASP-Ian Redmond Conservation Award, a grant co-funded by Remembering Great Apes and Born Free Foundation (BFF). The award was used to increase local awareness about the importance of Gishwati chimpanzees. The main goal of this project was to ensure extensive awareness among local community about the importance of preserving the Gishwati chimpanzees and the best practices to reduce transmissible diseases between people, chimpanzees and livestock. The project was implemented around Gishwati forest the northern part of Gishwati-Mukura National Park (GMNP). This park is home for a number of threatened primate species including eastern chimpanzees (Pan Troglodytes schweinfurthii, listed as endangered species on the IUCN Red List); golden monkeys (Cercopithecus mitis kandti, listed as endangered); mountain monkeys (Cercopithecus l’hoesti, listed as vulnerable); a large number of plant species and more than 200 bird species. The project was implemented during 12 months. During the project start FHA was visited by Margot Raggett, the founder of Remembering Great Apes and Ian Redmond. These visits were done just to meet the FHA team, visit the Gishwati forest, hear its conservation story, the work being done, and the contribution of this project on this new park conservation. Fig 1: Margot Raggett during her visit in the Fig 2: Ian Redmond with the Vice Mayor of Gishwati forest Rutsiro district and Ms. -

SYLLABUS HISTORY and GEOGRAPHY CHAMINADE UNIVERSITY WILLIS HENRY MOORE a VIDEO-MOVIE EXTRA There Are Som E Movies And/Or Video T

SYLLABUS HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY CHAMINADE UNIVERSITY WILLIS HENRY MOORE A VIDEO-MOVIE EXTRA There are som e movies and/or Video tapes which pertain to this course . You may wish to consider renting and watching one or more of these . WATCH THE VIDEO - - WRITE A REPORT : Name of Movie watched, date, who, what, when, where, etc - - One good paragraph summarizing the plot or purpose of the film - - - One paragraph of critique : THIS IS MOST IMPORTANT Inlcude your ideas of the film, what was shown, how, achy, point of view of filmmaker, technical excllence of film . "I would/would not recommend this film to others in .this course because . ." IF YOU DO A CREDIBLE JOB, that is, if it seems you watched the film, paid attention, and thought about it, you will receive one bonus point (towards that needed for the grade you want .) HISTORY - -THE WORLD SINCE 1500 .a partial list of video movies which pertain to this class, . A WORLD APART (Safrica) UNSETTLED LAND (Palestine) WAR & REMEMBRANCE SERIES OF 12 THE BOUNTY BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI BURN-Caribbean & Slavery RETURN TO SNOWY RIVER Australia TAI PAN - China SHAKAZULU - e Africa BATTLE OF BRITAIN--WWII THE MISSION--1986 Cannes Palm d'or OLD GRINGO - Mexico FORBIDDEN--Nazi THE DOCTOR & THE DEVILS-Victo rian BORN ON 9th JULY - Vietnam MUSSOLINI GALLIPOLI - WWI ELENI - Greek Civil War 1948 EMPIRE OF THE SUN - WWII-China ENOLA GAY : HIROSHIMA EVERYTIME WE SAY GOODBYE-Israel EYE OF THE NEEDLE-WWII EXODUS DEADLINE-Lebanon DR ZHIVAGO CRY IN THE DARK -Australia CRY FREEDOM -S Africa DAMIEN : THE LEPER -

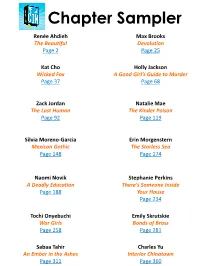

Chapter Sampler

Chapter Sampler Renée Ahdieh Max Brooks The Beautiful Devolution Page 2 Page 25 Kat Cho Holly Jackson Wicked Fox A Good Girl’s Guide to Murder Page 37 Page 68 Zack Jordan Natalie Mae The Last Human The Kinder Poison Page 92 Page 119 Silvia Moreno-Garcia Erin Morgenstern Mexican Gothic The Starless Sea Page 148 Page 174 Naomi Novik Stephanie Perkins A Deadly Education There’s Someone Inside Page 188 Your House Page 234 Tochi Onyebuchi Emily Skrutskie War Girls Bonds of Brass Page 258 Page 281 Sabaa Tahir Charles Yu An Ember in the Ashes Interior Chinatown Page 311 Page 360 The Beautiful Renée Ahdieh Click here to learn more about this book! RENé E AHDIEH G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS G. P. Putnam’s Sons an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, New York Copyright © 2019 by Renée Ahdieh. Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. G. P. Putnam’s Sons is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC. Visit us online at penguinrandomhouse.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 9781524738174 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Design by Theresa Evangelista. Text set in Warnock Pro. -

Jane Goodall: a Timeline 3

Discussion Guide Table of Contents The Life of Jane Goodall: A Timeline 3 Growing Up: Jane Goodall’s Mission Starts Early 5 Louis Leakey and the ‘Trimates’ 7 Getting Started at Gombe 9 The Gombe Community 10 A Family of Her Own 12 A Lifelong Mission 14 Women in the Biological Sciences Today 17 Jane Goodall, in Her Own Words 18 Additional Resources for Further Study 19 © 2017 NGC Network US, LLC and NGC Network International, LLC. All rights reserved. 2 Journeys in Film : JANE The Life of Jane Goodall: A Timeline April 3, 1934 Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall is born in London, England. 1952 Jane graduates from secondary school, attends secretarial school, and gets a job at Oxford University. 1957 At the invitation of a school friend, Jane sails to Kenya, meets Dr. Louis Leakey, and takes a job as his secretary. 1960 Jane begins her observations of the chimpanzees at what was then Gombe Stream Game Reserve, taking careful notes. Her mother is her companion from July to November. 1961 The chimpanzee Jane has named David Greybeard accepts her, leading to her acceptance by the other chimpanzees. 1962 Jane goes to Cambridge University to pursue a doctorate, despite not having any undergraduate college degree. After the first term, she returns to Africa to continue her study of the chimpanzees. She continues to travel back and forth between Cambridge and Gombe for several years. Baron Hugo van Lawick, a photographer for National Geographic, begins taking photos and films at Gombe. 1964 Jane and Hugo marry in England and return to Gombe. -

Good News for Gorillas As Poachers Change Their Ways

issue 44 autumn/winter 2013 the gorilla organization Good news for gorillas as Letter from the poachers change their ways Virungas Rubuguri is a small town on the Fighting and general unrest is, sadly, southern tip of Bwindi Impenetrable just the way of life here in eastern Forest, Uganda. For generations, the DR Congo. Since I last wrote, the men of this community would enter insecurity had eased only to start up the forests to hunt for bushmeat, once again. with sons learning poaching from But, like everyone else here, their fathers and, in turn, passing we conservationists have learned on their knowledge to the next to carry on working. If everything generation in a vicious cycle. stopped when there was fighting, While they only ever set traps nothing would ever be done! to catch small mammals to feed So, despite the troubles, themselves and their families, all it’s been a busy too often mountain gorillas would and productive become entangled in the crude traps, time here in the sometimes with fatal consequences. Virungas. “We never went to school, we For starters, were always too busy working in the we welcomed forest,” explains a former poacher Gorillas will remain in peril as long as poachers enter the forests in our Chairman Ian who wants to remain anonymous. search of food Redmond over the “Yes, there were risks – we could summer. He visited be arrested, or even shot – but we their experience and knowledge of being taught how to grow a range our resource centre in needed to eat and to provide for our the forests, they were employed to of crops, with special classes in Goma, as well as meeting families and this was the only way. -

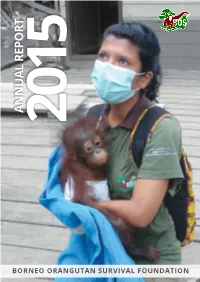

A L Repo R T 2015

T R L REPO A ANNU 2015 BORNEO ORANGUTAN SURVIVBOSAL Foundation FOUND - Annual ReportATION 2015 1 VISION &MISSION BOS FOUNDATION VISION “To achieve Bornean orangutan and habitat conservation in collaboration with local stakeholders.” BOS FOUNDATION MISSION 1. Accelerate the release of Bornean orangutans from ex-situ to in-situ locations 2. Encourage the protection of Bornean orangutans and their habitat 3. Increase the empowerment of communities surrounding orangutan habitat 4. Support research and education activities for the conservation of Bornean orangutans and their habitat 5. Promote the participation of and partnership with all stakeholders 6. Strengthen institutional capacity 2 BOS Foundation - Annual Report 2015 BOS Foundation - Annual Report 2015 3 PROGRAMS AND STRATEGIC ACTIVITIES BOS FOUNDATION STRATEGIC ACTIVITIES • Rescue, rehabilitation and reintroduction of orangutans and other protected species (sun bears), obtaining governmental permissions and approvals for reintroduction sites, translocation activities and post-release and translocation monitoring • Orangutan habitat conservation, comprising management of wild orangutan habitat in the Mawas Area, Central Kalimantan, management of translocation and reintroduction sites, management of orangutan and sun bear conservation areas and facilitation of Best Management Practices (BMP) of orangutan habitat within other land-uses • Involvement and empowerment of local communities, enhanced communication and publications, cooperation with stakeholders, conservation related research