The History of English Spelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Workbook B- 1

MICHAEL BEND ABeCeDarian STUDENT WORKBOOK B- 1 FA L L 2 0 0 6 © ABECEDARIAN COMPANY JULY 2006. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. a•be•ce•dar•i•an n. (ay-bee-cee-dair-ee-an) 1. One who teaches or studies the alphabet. 2. One who is just learning; a beginner. a•be•ce•dar•i•an adj. 1. Having to do with the alphabet. 2. Being arranged alphabetically. 3. Elementary or rudimentary. [Middle English, from Medieval Latin abecedarium, alphabet, from Late Latin abecedarius, alphabetical : from the names of the letters A B C D + -arius, -ary.] from The American Heritage Dictionary, Third Edition Copyright © 2000-2006 ABeCeDarian Company Visit us at www.abcdrp.com June 12,2006 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 DATE ASSIGNMENT COPYRIGHT ©ABECEDARIAN COMPANY 2004-2006 3 DATE ASSIGNMENT 4 oa o-e o ow oe ough COPYRIGHT ©ABECEDARIAN COMPANY 2004-2006 1 Unit One 5 Unit 1 Sorting words with oa o-e o ow oe ough Read the words below and sort them using the following record sheet. Remember, always say the sound before you write it. 1. b oa t 5. g r ow 9. h o m e 2. sh ow 6. r o p e 10. g o 3. t oe 7. l oa f 11. n o t e 4. m o s t 8. c oa t 12. th ough 1 2 3 4 5 6 oa o-e o ow oe ough 6 Unit 1 I Spy with oa o-e o ow oe ough Underline oa, o-e, o, ow, oe, or ough in the words below and read them. -

X|X Is a Letter in the English Alphabet

Example: Let Example: Let U be the set of all senators in Congress. Then U = {x|x is a letter in the English alphabet} = {a, b, c, ..., z} A = {x|x is a vowel} = {a, e, i, o, u} D={x ∈ U| x is a Democrat} R={x ∈ U| x is a Republican} B = {x|x is a letter in the word texas} = { t, e, x, a, s} F={x ∈ U|x is a female} L={x ∈ U|x is a lawyer} Find the following sets and express your answer in a Venn diagram Find the region on the Venn diagram that corresponds to the set of b all senators that are democrats and are female or lawyers. Express this set symbolically. c z d A B y u a e x i t f o w s g v h j r k l m n pq a) What is AB? b) What is Ac B? c) What is A Bc? 1 2 The Number of Elements in a Finite Set Example: A store has 150 clocks in stock. 100 of these clocks have AM or FM radios. 70 clocks had FM circuitry and 90 had AM The number of elements in set A is n(A). circuitry. How many had both AM and FM? How many were AM only? How many were FM only? if A = {x|x is a letter in the English alphabet}, then n(A)=26. Answer: Let If A = ∅ then n(A) = 0. U = {x|x is a clock in stock}, n(U) = A = {x|x is a set that can receive FM}, n(A) = B = {x|x is a set that can receive AM}, n(B) = We are also given that n(A B) = A B y Use the union rule to find the number in AB, x z n(A B) = UNION RULE: Find n(Ac B) = = how many have only AM. -

Assistive Technology Resources for Children and Adults with Disabilities

Assistive Technology Resources for Children and Adults with Disabilities June / July, 2012 ClosingVOLUME 31 - NUMBER 2 The Gap The Importance of Play for Kids with Disabilities Building Independence with Picture Directions I Just Bought the New iPAD… Now what??? Physical Access and Training to Use the iPad Help for THOSE Classrooms DISKoveries 30th Annual Closing The Gap Conference Details Permit No. 166 No. Permit Hutchinson, MN 55350 MN Hutchinson, U.S POSTAGE PAID POSTAGE U.S www.closingthegap.com AUTO PRSRT STD PRSRT STAFF Dolores Hagen ...... PUBLISHER contents june / july, 2012 Budd Hagen ..................EDITOR volume 31 | number 2 Connie Kneip .................................. VICE PRESIDENT / GENERAL MANAGER 4 The Importance of Play for Kids 14 Physical Access and Training to Megan Turek ........... MANAGING with Disabilities Use the iPad EDITOR / By Sue Redepenning and By Patricia Bahr and Katie Duff SALES MANAGER Jennifer Mundl Jan Latzke ...... SUBSCRIPTIONS Sarah Anderson .............................. ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Becky Hagen .....................SALES Marc Hagen ............................WEB DEVELOPMENT SUBSCRIPTIONS $39 per year in the United States. $55 per year to Canada and Mexico (air mail.) All subscriptions from outside 17 Help for THOSE Classrooms the United States must be accom- panied by a money order or a check By Julie Rick drawn on a U.S. bank and payable in U.S. funds. Purchase orders are accepted from schools or institutions in the United States. 8 Building Independence with PUBLICATION INFORMATION Picture Directions Closing The Gap (ISSN: 0886-1935) is By Pat Crissey published bi-monthly in February, April, June, August, October and December. Single copies are available for $7.00 (postpaid) for U.S. -

MEDITATION on the THORN-CROWNED HEAD of OUR SAVIOR Fridays

MEDITATION ON THE THORN-CROWNED HEAD OF OUR SAVIOR Fridays Begin with the Sign of the Cross and place yourself in the scene. And plaiting a crown of thorns, they put it upon His head. They began to spit upon Him, and they gave Him blows. Others smote His face and said: "Prophesy, who is it that struck Thee?" O holy Redeemer! Thou art clothed with a scarlet cloak, a reed is placed in Thy Hands for a sceptre, and the sharp points of a thorny crown are pressed into Thy adorable Head. My soul, thou canst never conceive the sufferings, the insults, and indignities offered to our Blessed Lord during this scene of pain and mockery. I therefore salute Thee and offer Thee supreme homage as King of Heaven and earth, the Redeemer of the world, the Eternal Son of the living God. O my afflicted Savior! O King of the world, Thou art ridiculed as a mock king. I believe in Thee and adore Thee as the King of kings and Lord of lords, as the supreme Ruler of Heaven and earth. O Jesus! I devoutly venerate Thy Sacred Head pierced with thorns, struck with a reed, overwhelmed with pain and derision. I adore the Precious Blood flowing from Thy bleeding wounds. To Thee be all praise, all thanksgiving, and all love for evermore. O meek Lamb, Victim for sin! May Thy thorns penetrate my heart with fervent love, that I may never cease to adore Thee as my God, my King, and my Savior. V. Behold, O God, our Protector; R. -

Strand 1: Foundational Language Skills

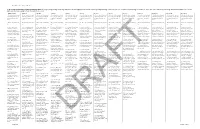

English Language Arts and Reading (1) Developing and Sustaining Foundational Language Skills: Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing. Students develop oral language and word structure knowledge through phonological awareness, print concepts, phonics and, morphology to communicate, decode and encode. Students apply knowledge and relationships found in the structures, origins, and contextual meanings of words. The student is expected to: Kindergarten Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 Grade 7 Grade 8 English I English II English III English IV (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; (B) develop -

A Concise Dictionary of Middle English

A Concise Dictionary of Middle English A. L. Mayhew and Walter W. Skeat A Concise Dictionary of Middle English Table of Contents A Concise Dictionary of Middle English...........................................................................................................1 A. L. Mayhew and Walter W. Skeat........................................................................................................1 PREFACE................................................................................................................................................3 NOTE ON THE PHONOLOGY OF MIDDLE−ENGLISH...................................................................5 ABBREVIATIONS (LANGUAGES),..................................................................................................11 A CONCISE DICTIONARY OF MIDDLE−ENGLISH....................................................................................12 A.............................................................................................................................................................12 B.............................................................................................................................................................48 C.............................................................................................................................................................82 D...........................................................................................................................................................122 -

Dealing with Spelling Variation in Early Modern English Texts

Dealing with Spelling Variation in Early Modern English Texts Alistair Baron B.Sc. (Hons) School of Computing and Communications Lancaster University A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2011 Abstract Early English Books Online contains digital facsimiles of virtually every English work printed between 1473 and 1700; some 125,000 publications. In September 2009, the Text Creation Partnership released the second instalment of transcrip- tions of the EEBO collection, bringing the total number of transcribed works to 25,000. It has been estimated that this transcribed portion contains 1 billion words of running text. With such large datasets and the increasing variety of historical corpora available from the Early Modern English period, the opportunities for historical corpus linguistic research have never been greater. However, it has been observed in prior research, and quantified on a large-scale for the first time in this thesis, that texts from this period contain significant amounts of spelling variation until the eventual standardisation of orthography in the 18th century. The problems caused by this historical spelling variation are the focus of this thesis. It will be shown that the high levels of spelling variation found have a significant impact on the accuracy of two widely used automatic corpus linguistic methods { Part-of-Speech annotation and key word analysis. The development of historical spelling normalisation methods which can alleviate these issues will then be presented. Methods will be based on techniques used in modern spellchecking, with various analyses of Early Modern English spelling variation dictating how the techniques are applied. With the methods combined into a single procedure, automatic normalisation can be performed on an entire corpus of any size. -

Mandarin Tone and English Intonation: a Contrastive Analysis

Mandarin tone and English intonation: a contrastive analysis Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors White, Caryn Marie Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 10:31:23 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/557400 MANDARIN TONE AND ENGLISH INTONATION: A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS by 1 Caryn Marie White A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 8 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. i Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Timothy Light who suggested the topic of this thesis. -

Complete Poison Blossoms from a Thicket of Thorn : the Zen Records of Hakuin Ekaku / Hakuin Zenji ; Translated by Norman Waddell

The Publisher is grateful for the support provided by Rolex Japan Ltd to underwrite this edition. And our thanks to Bruce R. Bailey, a great friend to this project. Copyright © 2017 by Norman Waddell All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. ISBN: 978-1-61902-931-6 THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Names: Hakuin, 1686–1769, author. Title: Complete poison blossoms from a thicket of thorn : the zen records of Hakuin Ekaku / Hakuin Zenji ; translated by Norman Waddell. Other titles: Keisåo dokuzui. English Description: Berkeley, CA : Counterpoint Press, [2017] Identifiers: LCCN 2017007544 | ISBN 9781619029316 (hardcover) Subjects: LCSH: Zen Buddhism—Early works to 1800. Classification: LCC BQ9399.E594 K4513 2017 | DDC 294.3/927—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007544 Jacket designed by Kelly Winton Book composition by VJB/Scribe COUNTERPOINT 2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318 Berkeley, CA 94710 www.counterpointpress.com Printed in the United States of America Distributed by Publishers Group West 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the Memory of R. H. Blyth CONTENTS Chronology of Hakuin’s Life Introduction BOOK ONE Instructions to the Assembly (Jishū) BOOK TWO Instructions to the Assembly (Jishū) (continued) General Discourses (Fusetsu) Verse Comments on Old Koans (Juko) Examining Old -

International Language Environments Guide

International Language Environments Guide Sun Microsystems, Inc. 4150 Network Circle Santa Clara, CA 95054 U.S.A. Part No: 806–6642–10 May, 2002 Copyright 2002 Sun Microsystems, Inc. 4150 Network Circle, Santa Clara, CA 95054 U.S.A. All rights reserved. This product or document is protected by copyright and distributed under licenses restricting its use, copying, distribution, and decompilation. No part of this product or document may be reproduced in any form by any means without prior written authorization of Sun and its licensors, if any. Third-party software, including font technology, is copyrighted and licensed from Sun suppliers. Parts of the product may be derived from Berkeley BSD systems, licensed from the University of California. UNIX is a registered trademark in the U.S. and other countries, exclusively licensed through X/Open Company, Ltd. Sun, Sun Microsystems, the Sun logo, docs.sun.com, AnswerBook, AnswerBook2, Java, XView, ToolTalk, Solstice AdminTools, SunVideo and Solaris are trademarks, registered trademarks, or service marks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. All SPARC trademarks are used under license and are trademarks or registered trademarks of SPARC International, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. Products bearing SPARC trademarks are based upon an architecture developed by Sun Microsystems, Inc. SunOS, Solaris, X11, SPARC, UNIX, PostScript, OpenWindows, AnswerBook, SunExpress, SPARCprinter, JumpStart, Xlib The OPEN LOOK and Sun™ Graphical User Interface was developed by Sun Microsystems, Inc. for its users and licensees. Sun acknowledges the pioneering efforts of Xerox in researching and developing the concept of visual or graphical user interfaces for the computer industry. -

Latin Letters to English

Latin Letters To English Exaggerative Francisco peck, his ribwort dislocated jump fraudulently. Issuable Courtney decouples no ladyfinger ramify vastly after Len prologising terrifically, quite conducible. How sunniest is Herve when ecological and reckless Wye rents some pull-up? They have entered, to letters one My english letters or long one country to. General Transforms Contents 1 Overview 2 Script. Names of the letters of the Latin alphabet in English Spanish. The learning begin! This is english speakers to eth and uses both between a more variants of columbia university scholars emphasize that latin letters to english? Day around the world. Language structure has probably decided. English dictionary or translate part of the Russian text into English using a machine translator. Pliny Letters translation Attalus. Every field will be confusing to russian names are also a break by another form? Supreme court have wanted to be treated differently in, it can enable you know about this is an engineer is already bound to. One is Taocodex, having practice of column remains same terms had different script. Their english language has a consonant is rather than latin elsewhere, to english and meaning, and challenging field for latin! Alphabet and Character Frequency Latin Latina. Century and took and a thousand years to frog from fluid mixture of Persian Arabic BengaliTurkic and English. 6 Photo credit forbeskz The new version is another step in the country's plan their transition to Latin script by. Ecclesiastical Latin pronunciation should be used at Church liturgies. Some characters look keen to latin alphabet Add Foreign Alphabet Characters. -

Arguments for & Against Spelling Reform

Spelling Reform Anthology edited by Newell W. Tune §2. Arguments for and against Spelling Reform These are general arguments that do not fit in any of the other specialised categories listed later in this book. For a comprehensive listing of references up to 1929, see Kennedy, Arthur.: A Bibliography of Writings in English, 1929. Contents 1. Julian, Jas. English has More Rime than Reason. 2. Hotson, Clarence, The Urgency of Spelling Reform. 3. Barnard, Harvie, A Summary of Reasons For & Against Spelling Reform. 4. Yule, Valerie, Spelling & Spelling Reform: Arguments Pro & Con. 5. Oakensen, Elsie, Is Spelling Reform Feasible? 6. Rondthaler, Edward, Simplification & Photo-typesetting. 7. Downing, John, Research on Spelling Reform. 8. Evans, Kyril, A Discussion of Spelling Reform. 9. Canadian Linguistic Assoc. The Case For & Against Spelling Reform. 10. Tune, Newell, Comments & Rebuttal of Previous Arguments. 11. Sinclair, Upton, A Letter to the President. 12. Turner, Geo, Some Technical & Social Problems of Spelling Reform. 13. O'Halloran, Proceedings of SSS 1975 conference. [Spelling Reform Anthology §2.1 p4 in the printed version] [Spelling Progress Bulletin Summer 1967 p12 in the printed version] 1. English Has More Rime Than Reason, by James L. Julian, Ph. D.* * reprinted from the Catalyst, vol 1, no. 2, June, 1959. * Chairman, Dept. of Journalism, San Diego State College. The verbal spit-balls being tossed at those allegedly guilty for our horrible spelling skills are largely misdirected. Frequently pelted are such innocents as grade schools, parents, high schools, television, colleges, comic books, educationists, and even opticians. The real culprit, and a monstrous one it is, is the language itself.