Arguments for & Against Spelling Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Workbook B- 1

MICHAEL BEND ABeCeDarian STUDENT WORKBOOK B- 1 FA L L 2 0 0 6 © ABECEDARIAN COMPANY JULY 2006. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. a•be•ce•dar•i•an n. (ay-bee-cee-dair-ee-an) 1. One who teaches or studies the alphabet. 2. One who is just learning; a beginner. a•be•ce•dar•i•an adj. 1. Having to do with the alphabet. 2. Being arranged alphabetically. 3. Elementary or rudimentary. [Middle English, from Medieval Latin abecedarium, alphabet, from Late Latin abecedarius, alphabetical : from the names of the letters A B C D + -arius, -ary.] from The American Heritage Dictionary, Third Edition Copyright © 2000-2006 ABeCeDarian Company Visit us at www.abcdrp.com June 12,2006 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 DATE ASSIGNMENT COPYRIGHT ©ABECEDARIAN COMPANY 2004-2006 3 DATE ASSIGNMENT 4 oa o-e o ow oe ough COPYRIGHT ©ABECEDARIAN COMPANY 2004-2006 1 Unit One 5 Unit 1 Sorting words with oa o-e o ow oe ough Read the words below and sort them using the following record sheet. Remember, always say the sound before you write it. 1. b oa t 5. g r ow 9. h o m e 2. sh ow 6. r o p e 10. g o 3. t oe 7. l oa f 11. n o t e 4. m o s t 8. c oa t 12. th ough 1 2 3 4 5 6 oa o-e o ow oe ough 6 Unit 1 I Spy with oa o-e o ow oe ough Underline oa, o-e, o, ow, oe, or ough in the words below and read them. -

Assistive Technology Resources for Children and Adults with Disabilities

Assistive Technology Resources for Children and Adults with Disabilities June / July, 2012 ClosingVOLUME 31 - NUMBER 2 The Gap The Importance of Play for Kids with Disabilities Building Independence with Picture Directions I Just Bought the New iPAD… Now what??? Physical Access and Training to Use the iPad Help for THOSE Classrooms DISKoveries 30th Annual Closing The Gap Conference Details Permit No. 166 No. Permit Hutchinson, MN 55350 MN Hutchinson, U.S POSTAGE PAID POSTAGE U.S www.closingthegap.com AUTO PRSRT STD PRSRT STAFF Dolores Hagen ...... PUBLISHER contents june / july, 2012 Budd Hagen ..................EDITOR volume 31 | number 2 Connie Kneip .................................. VICE PRESIDENT / GENERAL MANAGER 4 The Importance of Play for Kids 14 Physical Access and Training to Megan Turek ........... MANAGING with Disabilities Use the iPad EDITOR / By Sue Redepenning and By Patricia Bahr and Katie Duff SALES MANAGER Jennifer Mundl Jan Latzke ...... SUBSCRIPTIONS Sarah Anderson .............................. ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Becky Hagen .....................SALES Marc Hagen ............................WEB DEVELOPMENT SUBSCRIPTIONS $39 per year in the United States. $55 per year to Canada and Mexico (air mail.) All subscriptions from outside 17 Help for THOSE Classrooms the United States must be accom- panied by a money order or a check By Julie Rick drawn on a U.S. bank and payable in U.S. funds. Purchase orders are accepted from schools or institutions in the United States. 8 Building Independence with PUBLICATION INFORMATION Picture Directions Closing The Gap (ISSN: 0886-1935) is By Pat Crissey published bi-monthly in February, April, June, August, October and December. Single copies are available for $7.00 (postpaid) for U.S. -

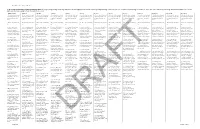

Strand 1: Foundational Language Skills

English Language Arts and Reading (1) Developing and Sustaining Foundational Language Skills: Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing. Students develop oral language and word structure knowledge through phonological awareness, print concepts, phonics and, morphology to communicate, decode and encode. Students apply knowledge and relationships found in the structures, origins, and contextual meanings of words. The student is expected to: Kindergarten Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 Grade 7 Grade 8 English I English II English III English IV (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; (B) develop -

Mandarin Tone and English Intonation: a Contrastive Analysis

Mandarin tone and English intonation: a contrastive analysis Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors White, Caryn Marie Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 10:31:23 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/557400 MANDARIN TONE AND ENGLISH INTONATION: A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS by 1 Caryn Marie White A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 8 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. i Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Timothy Light who suggested the topic of this thesis. -

Sound Familiesfamilies Resources for Sound Families

Play to learn Dyslexia, Scotland Education Conference Saturday, 25 September 2010 Learn to play SoundSound FamiliesFamilies Resources for Sound Families • Overview for vowels • Overview for consonants • Flippers • Highlighter pens • Writing pens • Worksheets •Posters • Smart board/laptop resources • Folder for work • Games • Activities • Overlays for projector if not using a smart board. SHORT Vowel Families a ea au e ea ai i ai y u ui o a aw au augh ough al awe ou ant heart laugh egg head said sit fountain cylinderbusy build got ball jaw autumn taught bought walk awe cough and end read again his captain mythbusiness built hot want claw haul daughter fought talk trough u oouo-e oo oe oi oy ow ou o cupMonday touch someflood does join toy now out bo luckwork rough comeblood doesn'tLONG Vowel Sounds boil joy brow shout p ay ey a-e yeigh ai ei eig ea ee ea ei ie ey iay e-e sayvalley gate sunnyeight rain vein reignbreak feet beat receive chief key skiquay here daythey cake happyweight nail rein feignsteak sleep leap deceit grief cay eve i i-e uy ie ighy ye eigh o oe ow o-e ougheau ew oa mildpine guy lie highcry bye height so toe blow bone thoughplateau sew goat wildwhite buy tie nightfly rye sleight go foe know home doughbeau float u oooewueouuiwo oughoe u-e eu e-e u-e iew eu eau ew ue u flu who book new glue you fruittwo through shoe rude pleurisy ewe June view feu beauty stew cue circular super to foodfewtrue soup suit canoeflute tune review feud few due conduit CONSONANT Families b bb bu c k ck ch lk cu que qu ch tch d dd tub sobbed build -

2013 AHA Acute Ischemic Stroke Early Management Guideline

AHA/ASA Guideline lww Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. XXX Endorsed by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and Congress of Neurological Surgeons Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS, FAHA, Chair; Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, FAHA, Vice Chair; Harold P. Adams, Jr, MD, FAHA; Askiel Bruno, MD, MS; J.J. (Buddy) Connors, MD; Downloaded from Bart M. Demaerschalk, MD, MSc; Pooja Khatri, MD, MSc, FAHA; Paul W. McMullan, Jr, MD, FAHA; Adnan I. Qureshi, MD, FAHA; Kenneth Rosenfield, MD, FAHA; Phillip A. Scott, MD, FAHA; Debbie R. Summers, RN, MSN, FAHA; David Z. Wang, DO, FAHA; Max Wintermark, MD; Howard Yonas, MD; on behalf of the American Heart Association Stroke http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease, and Council on Clinical Cardiology Background and Purpose—The authors present an overview of the current evidence and management recommendations for evaluation and treatment of adults with acute ischemic stroke. The intended audiences are prehospital care providers, physicians, allied health professionals, and hospital administrators responsible for the care of acute ischemic stroke patients within the first 48 hours from stroke onset. These guidelines supersede the prior 2007 guidelines and 2009 updates. by guest on July 12, 2017 Methods—Members of the writing committee were appointed by the American Stroke Association Stroke Council’s Scientific Statement Oversight Committee, representing various areas of medical expertise. -

Dario Cassina High School Student Handbook

DARIO CASSINA HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT HANDBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS BELL SCHEDULES ...................................................................................................................... 3 ATTENDANCE (ED. CODE 48200) ................................................................................................ 4 ABSENCES ................................................................................................................................ 4 CLOSED CAMPUS ...................................................................................................................... 4 LEAVING DURING THE SCHOOL DAY ............................................................................................ 4 VISITORS ................................................................................................................................... 4 CODE OF CONDUCT ................................................................................................................... 5 CLASSES, CREDITS AND GRADUATION REQUIREMENTS ................................................................ 6 EARNING CREDITS ..................................................................................................................... 7 GRADING PERIODS FOR 2017-2018 ............................................................................................ 7 WORK PERMITS ......................................................................................................................... 7 PERTUSSIS/WHOOPING COUGH BOOSTER SHOT (TDAP).............................................................. -

The 44* Phonemes Following Is a List of the 44 Phonemes Along with The

The 44* Phonemes Following is a list of the 44 phonemes along with the letters of groups of letters that represent those sounds. Phoneme Graphemes** Examples (speech sound) (letters or groups of letters representing the most common spellings for the individual phonemes) Consonant Sounds: 1. /b/ b, bb big, rubber 2. /d/ d, dd, ed dog, add, filled 3. /f/ f, ph fish, phone 4. /g/ g, gg go, egg 5. /h/ h hot 6. /j/ j, g, ge, dge jet, cage, barge, judge 7. /k/ c, k, ck, ch, cc, que cat, kitten, duck, school, occur, antique, cheque 8. /l/ l, ll leg, bell 9. /m/ m, mm, mb mad, hammer, lamb 10. /n/ n, nn, kn, gn no, dinner, knee, gnome 11. /p/ p, pp pie, apple 12. /r/ r, rr, wr run, marry, write 13. /s/ s, se, ss, c, ce, sc sun, mouse, dress, city, ice, science 14. /t/ t, tt, ed top, letter, stopped 15. /v/ v, ve vet, give 16. /w/ w wet, win, swim 17 /y/ y, i yes, onion 18. /z/ z, zz, ze, s, se, x zip, fizz, sneeze, laser, is, was, please, Xerox, xylophone Source: Orchestrating Success in Reading by Dawn Reithaug (2002) Phoneme Graphemes** Examples (speech sound) (letters or groups of letters representing the most common spellings for the individual phonemes) Consonant Digraphs: 19. /th/ th thumb, thin, thing (not voiced) 20. /th/ th this, feather, then (voiced) 21. /ng/ ng, n sing, monkey, sink 22. /sh/ sh, ss, ch, ti, ci ship, mission, chef, motion, special 23. /ch/ ch, tch chip, match 24. -

The History of English Spelling

9781405190237_1_pre.qxd 6/15/11 9:00 Page iii The History of English Spelling Christopher Upward and George Davidson A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405190237_1_pre.qxd 6/15/11 9:00 Page vi 9781405190237_1_pre.qxd 6/15/11 9:00 Page i The History of English Spelling 9781405190237_1_pre.qxd 6/15/11 9:00 Page ii THE LANGUAGE LIBRARY Series editor: David Crystal The Language Library was created in 1952 by Eric Partridge, the great etymologist and lexicographer, who from 1966 to 1976 was assisted by his co-editor Simeon Potter. Together they commissioned volumes on the traditional themes of language study, with particular emphasis on the history of the English language and on the individual linguistic styles of major English authors. In 1977 David Crystal took over as editor, and The Language Library now includes titles in many areas of linguistic enquiry. The most recently published titles in the series include: Christopher Upward and The History of English Spelling George Davidson Geoffrey Hughes Political Correctness: A History of Semantics and Culture Nicholas Evans Dying Words: Endangered Languages and What They Have to Tell Us Amalia E. Gnanadesikan The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet David Crystal A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics, Sixth Edition Viv Edwards Multilingualism in the English- speaking World Ronald Wardhaugh Proper English: Myths and Misunderstandings about Language Gunnel Tottie An Introduction to American English Geoffrey Hughes A History of English Words Walter Nash Jargon Roger Shuy Language -

Stroke and Diabetes: a Dangerous Liaison

REVIEW Stroke and diabetes: a dangerous liaison SARAH L MACPHERSON, 1 CHRISTOPHER R SAINSBURY, 1 JESSE DAWSON, 2 GREGORY C JONES 1 Abstract diagnosed diabetes. 3 A prospective study of over 13,000 people Ischaemic stroke is a major cause of disability and death and showed that, in people with type 2 diabetes, the risk of death the incidence rate of ischaemic stroke is doubled in patients from myocardial infarction and stroke is increased two fold, in - who have diabetes. Admission hyperglycaemia in acute dependent of other known cardiovascular risk factors. 4 Thus, stroke patients is associated with higher mortality, longer diabetes increases the risk of stroke and the risk of death from hospital stay and worse functional outcome. However, it stroke . remains unclear whether hyperglycaemia is in fact a marker The definition of hyperglycaemia varies in stroke studies and of stroke severity or whether hyperglycaemia directly con - ranges from 6.1 mmol/L to >10 mmol/L glucose. Based on these tributes to brain damage. Potential mechanisms of hypergly - definitions, hyperglycaemia is found at presentation in 30–60% caemia related brain damage in stroke include acidosis, of all stroke patients. 5 Research has shown that acute hypergly - oxidative stress and reperfusion injury. Evidence suggests a caemia in stroke contributes to worse functional outcomes, potential benefit of treatment of hyperglycaemia with longer hospital admission and higher mortality. 6 There is uncer - insulin in acute stroke patients but the potential for morbid - tainty about what level of blood glucose contributes to un - ity caused hypoglycaemia should be considered. The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association favourable outcomes. -

Phonemes Visit the Dyslexia Reading Well

For More Information on Phonemes Visit the Dyslexia Reading Well. www.dyslexia-reading-well.com The 44 Sounds (Phonemes) of English A phoneme is a speech sound. It’s the smallest unit of sound that distinguishes one word from another. Since sounds cannot be written, we use letters to represent or stand for the sounds. A grapheme is the written representation (a letter or cluster of letters) of one sound. It is generally agreed that there are approximately 44 sounds in English, with some variation dependent on accent and articulation. The 44 English phonemes are represented by the 26 letters of the alphabet individually and in combination. Phonics instruction involves teaching the relationship between sounds and the letters used to represent them. There are hundreds of spelling alternatives that can be used to represent the 44 English phonemes. Only the most common sound / letter relationships need to be taught explicitly. The 44 English sounds can be divided into two major categories – consonants and vowels. A consonant sound is one in which the air flow is cut off, either partially or completely, when the sound is produced. In contrast, a vowel sound is one in which the air flow is unobstructed when the sound is made. The vowel sounds are the music, or movement, of our language. The 44 phonemes represented below are in line with the International Phonetic Alphabet. Consonants Sound Common Spelling alternatives spelling /b/ b bb ball ribbon /d/ d dd ed dog add filled /f/ f ff ph gh lf ft fan cliff phone laugh calf often /g/ g gg gh gu -

Spelling and Phonetic Inconsistencies in English: a Problem for Learners of English As a Foreign/Second Language Nneka Umera-Okeke

Spelling and Phonetic Inconsistencies in English: A Problem for Learners of English as a Foreign/Second Language Nneka Umera-Okeke Abstract: Spelling is simply the putting together of a number of letters of the alphabet in order to form words. In a perfect alphabet, every letter would be a phonetic symbol representing one sound and one only, and each sound would have its appropriate symbol. But it is not the case in English. English spelling is defective. It is a poor reflection of English pronunciation as we have not enough symbols to represent all the sounds of English. The problems of these inconsistencies to foreign and second language learners can not be over- emphasized. This study will look at the historical reasons for this problem; areas of these inconsistencies and make some suggestions to ease the problem of spelling and pronunciation for second and foreign language learners. Introduction: With the spread of literacy and the invention of printing came the development of written English with its confusing and inconsistent spellings becoming more and more apparent. Ideally, the spelling system should closely reflect pronunciation and in many languages that indeed is the case. Each sound of English language is represented by more than one written letter or by sequences of letters; and any letter of English represents more than one sound, or it may not represent any sound at all. There is lack of consistencies. Commenting on these inconsistencies, Vallins (1954) states: 64 African Research Review Vol. 2 (1) Jan., 2008 Professor Ernest Weekly in The English Language forcefully and uncompromisingly expresses the opinion that the spelling of English “is so far as its relation to the spoken word is concerned quite crazy…” At the early stage of writing, say as early as eighteenth century, people did not concern themselves with rules or accepted practices.