Spelling and Phonetic Inconsistencies in English: a Problem for Learners of English As a Foreign/Second Language Nneka Umera-Okeke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Brief March 2017 Publication #2017-16

Research Brief March 2017 Publication #2017-16 Flourishing From the Start: What Is It and How Can It Be Measured? Kristin Anderson Moore, PhD, Child Trends Christina D. Bethell, PhD, The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Introduction Initiative, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Every parent wants their child to flourish, and every community wants its Public Health children to thrive. It is not sufficient for children to avoid negative outcomes. Rather, from their earliest years, we should foster positive outcomes for David Murphey, PhD, children. Substantial evidence indicates that early investments to foster positive child development can reap large and lasting gains.1 But in order to Child Trends implement and sustain policies and programs that help children flourish, we need to accurately define, measure, and then monitor, “flourishing.”a Miranda Carver Martin, BA, Child Trends By comparing the available child development research literature with the data currently being collected by health researchers and other practitioners, Martha Beltz, BA, we have identified important gaps in our definition of flourishing.2 In formerly of Child Trends particular, the field lacks a set of brief, robust, and culturally sensitive measures of “thriving” constructs critical for young children.3 This is also true for measures of the promotive and protective factors that contribute to thriving. Even when measures do exist, there are serious concerns regarding their validity and utility. We instead recommend these high-priority measures of flourishing -

The Assignment of Grammatical Gender in German: Testing Optimal Gender Assignment Theory

The Assignment of Grammatical Gender in German: Testing Optimal Gender Assignment Theory Emma Charlotte Corteen Trinity Hall September 2018 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Assignment of Grammatical Gender in German: Testing Optimal Gender Assignment Theory Emma Charlotte Corteen Abstract The assignment of grammatical gender in German is a notoriously problematic phenomenon due to the apparent opacity of the gender assignment system (e.g. Comrie 1999: 461). Various models of German gender assignment have been proposed (e.g. Spitz 1965, Köpcke 1982, Corbett 1991, Wegener 1995), but none of these is able to account for all of the German data. This thesis investigates a relatively under-explored, recent approach to German gender assignment in the form of Optimal Gender Assignment Theory (OGAT), proposed by Rice (2006). Using the framework of Optimality Theory, OGAT claims that the form and meaning of a noun are of equal importance with respect to its gender. This is formally represented by the crucial equal ranking of all gender assignment constraints in a block of GENDER FEATURES, which is in turn ranked above a default markedness hierarchy *NEUTER » *FEMININE » *MASCULINE, which is based on category size. A key weakness of OGAT is that it does not specify what constitutes a valid GENDER FEATURES constraint. This means that, in theory, any constraint can be proposed ad hoc to ensure that an OGAT analysis yields the correct result. In order to prevent any constraints based on ‘postfactum rationalisations’ (Comrie 1999: 461) from being included in the investigation, the GENDER FEATURES constraints which have been proposed in the literature for German are assessed according to six criteria suggested by Enger (2009), which seek to determine whether there is independent evidence for a GENDER FEATURES constraint. -

Student Workbook B- 1

MICHAEL BEND ABeCeDarian STUDENT WORKBOOK B- 1 FA L L 2 0 0 6 © ABECEDARIAN COMPANY JULY 2006. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. a•be•ce•dar•i•an n. (ay-bee-cee-dair-ee-an) 1. One who teaches or studies the alphabet. 2. One who is just learning; a beginner. a•be•ce•dar•i•an adj. 1. Having to do with the alphabet. 2. Being arranged alphabetically. 3. Elementary or rudimentary. [Middle English, from Medieval Latin abecedarium, alphabet, from Late Latin abecedarius, alphabetical : from the names of the letters A B C D + -arius, -ary.] from The American Heritage Dictionary, Third Edition Copyright © 2000-2006 ABeCeDarian Company Visit us at www.abcdrp.com June 12,2006 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 DATE ASSIGNMENT COPYRIGHT ©ABECEDARIAN COMPANY 2004-2006 3 DATE ASSIGNMENT 4 oa o-e o ow oe ough COPYRIGHT ©ABECEDARIAN COMPANY 2004-2006 1 Unit One 5 Unit 1 Sorting words with oa o-e o ow oe ough Read the words below and sort them using the following record sheet. Remember, always say the sound before you write it. 1. b oa t 5. g r ow 9. h o m e 2. sh ow 6. r o p e 10. g o 3. t oe 7. l oa f 11. n o t e 4. m o s t 8. c oa t 12. th ough 1 2 3 4 5 6 oa o-e o ow oe ough 6 Unit 1 I Spy with oa o-e o ow oe ough Underline oa, o-e, o, ow, oe, or ough in the words below and read them. -

Influences on the Development of Early Modern English

Influences on the Development of Early Modern English Kyli Larson Wright This article covers the basic social, historical, and linguistic influences that have transformed the English language. Research first describes components of Early Modern English, then discusses how certain factors have altered the lexicon, phonology, and other components. Though there are many factors that have shaped English to what it is today, this article only discusses major factors in simple and straightforward terms. 72 Introduction The history of the English language is long and complicated. Our language has shifted, expanded, and has eventually transformed into the lingua franca of the modern world. During the Early Modern English period, from 1500 to 1700, countless factors influenced the development of English, transforming it into the language we recognize today. While the history of this language is complex, the purpose of this article is to determine and map out the major historical, social, and linguistic influences. Also, this article helps to explain the reasons for their influence through some examples and evidence of writings from the Early Modern period. Historical Factors One preliminary historical event that majorly influenced the development of the language was the establishment of the print- ing press. Created in 1476 by William Caxton at Westminster, London, the printing press revolutionized the current language form by creating a means for language maintenance, which helped English gravitate toward a general standard. Manuscripts could be reproduced quicker than ever before, and would be identical copies. Because of the printing press spelling variation would eventually decrease (it was fixed by 1650), especially in re- ligious and literary texts. -

The Role of Grammatical Gender in Noun-Formation: a Diachronic Perspective from Norwegian

The role of grammatical gender in noun-formation: A diachronic perspective from Norwegian Philipp Conzett 1. The relationship between gender and word-formation According to Corbett (1991: 1) “[g]ender is the most puzzling of the grammatical categories”. In modern languages, however, gender is most often seen as nothing more than an abstract inherent classificatory feature of nouns that triggers agreement in associated words. Given this perspec- tive of gender as a redundant category, the question arises of why it none- theless is so persistent in a great number of languages. This question has been answered inter alia by referring to the identifying and disambiguating function gender can have in discourse (e.g., Corbett 1991: 320–321). In this article further evidence is provided for viewing grammatical gender (henceforth gender) as an integral part of Cognitive Grammar, more spe- cifically the domain of word-formation. The relationship between grammatical gender and word-formation can be approached from (at least) two different angles. In literature dealing with gender assignment, characteristics of word-formation are often used as a base for assigning gender to nouns. This approach is presented in sec- tion 1.1. On the other hand, gender is described as a feature involved in the formation of new nouns. This perspective is introduced in 1.2. 1.1. Gender assignment based on word-formation Regularities between the gender of nouns and their derivational morphol- ogy can be detected in a number of languages. Gender can be tied to overt or covert derivational features. The former type is usually realized by suf- fixation, e.g., Norwegian klok (adj. -

English Spelling Among the Top Priorities In

Research in Language, 2016, vol. 2 DOI: 10.1515/rela-2016-0002 ENGLISH SPELLING AMONG THE TOP PRIORITIES IN PRONUNCIATION TEACHING : POLGLISH LOCAL VERSUS GLOBAL (ISED ) ERRORS IN THE PRODUCTION AND PERCEPTION OF WORDS COMMONLY MISPRONOUNCED MARTA NOWACKA Uniwersytet Rzeszowski [email protected] Abstract This paper presents the results of a questionnaire and recording-based study on production and recognition of a sample of 60 items from Sobkowiak’s (1996:294) ‘words commonly mispronounced’ by 143 first-year BA students majoring in English. 30 lexical items in each task represent 27 categories defined by Porzuczek (2015), each referring to one aspect of English phonotactics and/or spelling-phonology relations. Our aim is to provide evidence for the occurrence of local and globalised errors in Polglish speech. This experiment is intended to examine what types of errors, that is, seriously deformed words, whether avoidable, ‘either-or’ or unavoidable ones, as classified in Porzuczek (2015), are the most frequent in production and recognition of words. Our goal is to check what patterns concerning letter-to-sound relations, are not respected in the subjects’ production and recognition of an individual word and what rules should be explicitly discussed and practised in a phonetics course. The results of the study confirm the necessity for explicit instruction on the regularity rather than irregularity of English spelling in order to eradicate globalised and ‘either-or’ pronunciation errors in the speech of students. The avoidable globalised -

The English Language

The English Language Version 5.0 Eala ðu lareow, tæce me sum ðing. [Aelfric, Grammar] Prof. Dr. Russell Block University of Applied Sciences - München Department 13 – General Studies Winter Semester 2008 © 2008 by Russell Block Um eine gute Note in der Klausur zu erzielen genügt es nicht, dieses Skript zu lesen. Sie müssen auch die “Show” sehen! Dieses Skript ist der Entwurf eines Buches: The English Language – A Guide for Inquisitive Students. Nur der Stoff, der in der Vorlesung behandelt wird, ist prüfungsrelevant. Unit 1: Language as a system ................................................8 1 Introduction ...................................... ...................8 2 A simple example of structure ..................... ......................8 Unit 2: The English sound system ...........................................10 3 Introduction..................................... ...................10 4 Standard dialects ................................ ....................10 5 The major differences between German and English . ......................10 5.1 The consonants ................................. ..............10 5.2 Overview of the English consonants . ..................10 5.3 Tense vs. lax .................................. ...............11 5.4 The final devoicing rule ....................... .................12 5.5 The “th”-sounds ................................ ..............12 5.6 The “sh”-sound .................................. ............. 12 5.7 The voiced sounds / Z/ and / dZ / ...................................12 5.8 The -

TPS. 21 and 22 N., R. 11 E. by CLARENCE S. ROSS. INTRODUCTION. the Area Included in Tps. 21 and 22 N., R. 11 E., Lies in The

TPS. 21 AND 22 N., R. 11 E. By CLARENCE S. ROSS. INTRODUCTION. The area included in Tps. 21 and 22 N., R. 11 E., lies in the south eastern part of the Osage Reservation and in the eastern part of the Hominy quadrangle. (See fig. 1.) It may be reached from Skia took and Sperry, on the Midland Valley Railroad, about 4 miles to the east. Two major roads run west from these towns, following the valleys of Hominy and Delaware creeks, but the minor roads are very poor, and much of the area is difficult of access. The entire area is hilly and has a maximum relief of 400 feet. Most of the ridges are timbered, and farming is confined to the alluvial bottoms of the larger creeks. The areal geology of the Hominy quadrangle has been mapped on a scale of 2 miles to the inch in cooperation with the Oklahoma Geological Survey. The detailed structural examination of Tps. 21 and 22 N., R. 11 E., was made in March, April, May, and June, 1918, by the writer, Sidney Powers, W. S. W. Kew, and P. V. Roundy. All the mapping was done with plane table and telescope alidade. STRATIGRAPHY. EXPOSED ROCKS. The rocks exposed at the surface in this area belong to the middle Pennsylvanian, and consist of sandstone, shale, and limestone, ag gregating about 700 feet in thickness. Shale predominates, but sand stone and limestone form the prominent rock exposures. A few of the strata that may be used as key beds will be described for the benefit of those who may wish to do geologic work in the region. -

A Corpus·Based Investigation of Xhosa English In

A CORPUS·BASED INVESTIGATION OF XHOSA ENGLISH IN THE CLASSROOM SETTING A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS of RHODES UNIVERSITY by CANDICE LEE PLATT January 2004 Supervisor: Professor V.A de K1erk ABSTRACT This study is an investigation of Xhosa English as used by teachers in the Grahamstown area of the Eastern Cape. The aims of the study were firstly, to compile a 20 000 word mini-corpus of the spoken English of Xhosa mother tongue teachers in Grahamstown, and to use this data to describe the characteristics of Xhosa English used in the classroom context; and secondly, to assess the usefulness of a corpus-based approach to a study of this nature. The English of five Xhosa mother-tongue teachers was investigated. These teachers were recorded while teaching in English and the data was then transcribed for analysis. The data was analysed using Wordsmith Tools to investigate patterns in the teachers' language. Grammatical, lexical and discourse patterns were explored based on the findings of other researchers' investigations of Black South African English and Xhosa English. In general, many of the patterns reported in the literature were found in the data, but to a lesser extent than reported in literature which gave quantitative information. Some features not described elsewhere were also found . The corpus-based approach was found to be useful within the limits of pattern matching. 1I TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 CORPORA 1 1.2 BLACK SOUTH -

Graphemic Methods for Genderneutral

Graphemic Methods for GenderNeutral Writing Yannis Haralambous & Joseph Dichy Abstract. In this paper we present a model and a classification of graphemic genderneutral writing methods, we explore current practices in French, Ger man, Greek, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish languages, and we investigate in teractions between genderneutral writing forms and regular expressions. 1. Introduction: The General Issue of, and behind, Gender Neutral Writing The issue behind genderneutral writing is that of the representation of intergender relations carried by languages. What is at stake is the representation of equality, or not, between genders. The issue is also re ferred to as “inclusive writing,” which apparently refers to human rights, but does not cover all cases, i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons. The term “GenderNeutral Writing” is, in fact, both clearer and more inclusive. Generally speaking, languages are conservative, if not archaic. A sig nificant example is that of the idea of time, which is traditionally repre sented as a dot sliding along a straight line in a continuous movement. This has been a philosophical image of time since ancient Greek philoso phers and throughout the Middle Ages both in Arabic and European phi losophy, but can no longer be considered as a valid representation after 20th century existentialist philosophers and Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit. Yannis Haralambous 0000-0003-1443-6115 IMT Atlantique & LabSTICC UMR CNRS 6285 Brest, France [email protected] Joseph Dichy Professor of Arabic linguistics Lyon, France [email protected] Y. Haralambous (Ed.), Graphemics in the 21st Century. -

Assistive Technology Resources for Children and Adults with Disabilities

Assistive Technology Resources for Children and Adults with Disabilities June / July, 2012 ClosingVOLUME 31 - NUMBER 2 The Gap The Importance of Play for Kids with Disabilities Building Independence with Picture Directions I Just Bought the New iPAD… Now what??? Physical Access and Training to Use the iPad Help for THOSE Classrooms DISKoveries 30th Annual Closing The Gap Conference Details Permit No. 166 No. Permit Hutchinson, MN 55350 MN Hutchinson, U.S POSTAGE PAID POSTAGE U.S www.closingthegap.com AUTO PRSRT STD PRSRT STAFF Dolores Hagen ...... PUBLISHER contents june / july, 2012 Budd Hagen ..................EDITOR volume 31 | number 2 Connie Kneip .................................. VICE PRESIDENT / GENERAL MANAGER 4 The Importance of Play for Kids 14 Physical Access and Training to Megan Turek ........... MANAGING with Disabilities Use the iPad EDITOR / By Sue Redepenning and By Patricia Bahr and Katie Duff SALES MANAGER Jennifer Mundl Jan Latzke ...... SUBSCRIPTIONS Sarah Anderson .............................. ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Becky Hagen .....................SALES Marc Hagen ............................WEB DEVELOPMENT SUBSCRIPTIONS $39 per year in the United States. $55 per year to Canada and Mexico (air mail.) All subscriptions from outside 17 Help for THOSE Classrooms the United States must be accom- panied by a money order or a check By Julie Rick drawn on a U.S. bank and payable in U.S. funds. Purchase orders are accepted from schools or institutions in the United States. 8 Building Independence with PUBLICATION INFORMATION Picture Directions Closing The Gap (ISSN: 0886-1935) is By Pat Crissey published bi-monthly in February, April, June, August, October and December. Single copies are available for $7.00 (postpaid) for U.S. -

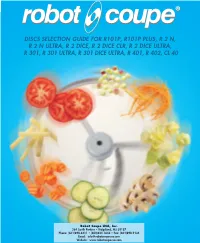

Discs Selection Guide for R101p, R101p Plus, R 2 N, R 2 N Ultra, R 2 Dice, R 2 Dice Clr, R 2 Dice Ultra, R 301, R 301 Ultra

R 301 Dice Ultra, R 402 and CL 40 ONLY Julienne Dicing R 2 Dice, R 2 Dice CLR, R 2 Dice Ultra ONLY R 101P, R 101P Plus, R 2 N, R 2 N CLR, R 2 N Ultra, R 2 Dice, R 2 Dice Ultra, R 301, R 301 Ultra, R 301 Dice Ultra, R 401, R 402 and CL 40 8x8 mm* 10x10 mm* 12x12 mm* (5/16” x 5/16”) (3/8” x 3/8”) (15/32” x 15/32”) Ref. 27113 Ref. 27114 Ref. 27298 Ref. 27264 Ref. 27290 DISCS SELECTION GUIDE FOR R101P, R101P PLUS, R 2 N, 2x2 mm 2x4 mm 2x6 mm Ref. 27265 (5/64” x 5/64”) (5/64” x 5/32”) (5/64” x 1/4”) R 2 N ULTRA, R 2 DICE, R 2 DICE CLR, R 2 DICE ULTRA, Ref. 27599 Ref. 27080 Ref. 27081 R 301, R 301 ULTRA, R 301 DICE ULTRA, R 401, R 402, CL 40 * Use Dice Cleaning Kit to Clean (ref. 39881) French Fries R 301 Dice Ultra, R 402 and CL 40 ONLY 8x8 mm 10x10 mm (5/16” x 5/16”) (3/8” x 3/8”) 4x4 mm 6x6 mm 8x8 mm Ref. 27116 Ref. 27117 (5/32”x 5/32”) (1/4”x 1/4”) (5/16” x 5/16”) Ref. 27047 Ref. 27610 Ref. 27048 Dice Cleaning Kit Reversible grid holder • One side for Smaller Dicing Unit's discs: R 2 Dice, R 301 Dice Ultra, R 402 and CL 40 • One side for Larger Dicing Unit's discs: R 502, R 602 V.V., CL 50, CL 50 Gourmet, CL 51, Cleaning tool CL 52, CL 55 and CL 60 dicing grids Dicing grid cleaning tool 5 mm (3/16”), 8 mm (5/16”) or 10 mm (3/8”) Robot Coupe USA, Inc.