The Environmental Effects of Forced Displacement in Burma's Karenni State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BURMA (MYANMAR) COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

BURMA (MYANMAR) COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 17 June 2011 BURMA (MYANMAR) 17 JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN BURMA FROM 16 MAY TO 17 JUNE 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON BURMA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 16 MAY AND 17 JUNE 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY (INDEPENDENCE (1948) – NOVEMBER 2010) ................................................ 3.01 Constitutional referendum – 2008....................................................................... 3.03 Build up to 2010 elections ................................................................................... 3.05 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS (NOVEMBER 2010 – MARCH 2011)....................................... 4.01 November 2010 elections .................................................................................... 4.01 Release of Aung San Suu Kyi ............................................................................. 4.13 Opening of Parliament ......................................................................................... 4.16 5. CONSTITUTION......................................................................................................... -

CDC) Dataset Codebook

The Categorically Disaggregated Conflict (CDC) Dataset Codebook (Version 1.0, 2015.07) (Presented in Bartusevičius, Henrikas (2015) Introducing the Categorically Disaggregated Conflict (CDC) dataset. Forthcoming in Conflict Management and Peace Science) The Categorically Disaggregated Conflict (CDC) Dataset provides a categorization of 331 intrastate armed conflicts recorded between 1946 and 2010 into four categories: 1. Ethnic governmental; 2. Ethnic territorial; 3. Non-ethnic governmental; 4. Non-ethnic territorial. The dataset uses the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset v.4-2011, 1946 – 2010 (Themnér & Wallensteen, 2011; also Gleditsch et al., 2002) as a base (and thus is an extension of the UCDP/PRIO dataset). Therefore, the dataset employs the UCDP/PRIO’s operational definition of an aggregate armed conflict: a contested incompatibility that concerns government and/or territory where the use of armed force between two parties, of which at least one is the government of a state, results in at least 25 battle-related deaths (Themnér, 2011: 1). The dataset contains only internal and internationalized internal armed conflicts listed in the UCDP/PRIO dataset. Internal armed conflict ‘occurs between the government of a state and one or more internal opposition group(s) without intervention from other states’ (ibid.: 9). Internationalized internal armed conflict ‘occurs between the government of a state and one or more internal opposition group(s) with intervention from other states (secondary parties) on one or both sides’(ibid.). For full definitions and further details please consult the 1 codebook of the UCDP/PRIO dataset (ibid.) and the website of the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University: http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/definitions/. -

Ethnic Armed Actors and Justice Provision in Myanmar

Ethnic Armed Actors and Justice Provision in Myanmar Brian McCartan and Kim Jolliffe October 2016 Preface As a result of decades of ongoing civil war, large areas of Myanmar remain outside government rule, or are subject to mixed control and governance by the government and an array of ethnic armed actors (EAAs). These included ethnic armed organizations, with ceasefires or in conflict with the state, as well as state-backed ethnic paramilitary organizations, such as the Border Guard Forces and People’s Militia Forces. Despite this complexity, order has been created in these areas, in large part through customary justice mechanisms at the community level, and as a result of justice systems administered by EAAs. Though the rule of law and the workings of Myanmar’s justice system are receiving increasing attention, the role and structure of EAA justice systems and village justice remain little known and therefore, poorly understood. As such, The Asia Foundation is pleased to present this research on justice provision and ethnic armed actors in Myanmar, as part of the Foundation’s Social Services in Contested Areas in Myanmar series. The study details how the village, and village-based mechanisms, are the foundation of stability and order for civilians in most of these areas. These systems have then been built through EAA justice systems, which maintain a hierarchy of courts above the village level. Understanding the continuity and stability of these village systems, and the heterogeneity of the EAA justice systems which work alongside them, is essential for understanding civilians’ experiences of justice and security across Myanmar, as well as the opportunities for positive change that exist in Myanmar’s ongoing peace process and governance reforms. -

3 Sides to Every Story

33 SSIDES TO EEVERY SSTORY A PROFILE OF MUSLIM COMMUNITIES IN THE REFUGEE CAMPS ON THE THAILAND BURMA BORDER THAILAND BURMA BORDER CONSORTIUM JULY 2010 Note on the Title: The “three sides” refers to the three self-identified sectors of Muslim communities in the camps, defined by the reasons for their presence in the camps (see “Muslim Lifestyle Practices and Preferences/ Socio-Cultural/ Self-identity”). Cover design: http://library.wustl.edu/subjects/islamic/MihrabIsfahan.jpg 2 33 SSIDES TO EEVERY SSTORY A PROFILE OF MUSLIM COMMUNITIES IN THE REFUGEE CAMPS ON THE THAILAND BURMA BORDER THAILAND BURMA BORDER CONSORTIUM JULY 2010 3 CONTENTS PAGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ……….......………………………………………………….……………………………. 7 SUMMARY OF STATISTICS BY RELIGION/CAMP ……………………………………………………………....... 9 PREFACE ……….......………………………………………………….……………………………………… 13 BACKGROUND INTRODUCTION OF ISLAM TO BURMA ………………………………………………………………………...... 15 DISPLACEMENT OF BURMESE MUSLIM COMMUNITIES INTO THAILAND ……..……………………………………… 15 Border-wide Camp-Specific Other Influxes CURRENT SITUATION PREVALENCE OF MUSLIM COMMUNITIES IN AND AROUND THE REFUGEE CAMPS ……..……………………. 19 Muslim Communities in Camps Muslim Communities Around the Camps Impacts on Camp Security LIFESTYLE PRACTICES AND PREFERENCES: SOCIO-CULTURAL: ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 21 o The “Three Sides” o Religion and Faith o Gender Roles o Romance, Marriage and Divorce o Social Inclusion FOOD AND SHELTER: ………….…...………………..…………………………….…………………….. 29 o Ration Collection/ Consumption o Ration/ Diet Supplementation -

Sold to Be Soldiers the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

October 2007 Volume 19, No. 15(C) Sold to be Soldiers The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Terminology and Abbreviations................................................................................2 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 The Government of Burma’s Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw ..................................6 Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment ...............................................9 Non-state Armed Groups....................................................................................11 The Local and International Response ............................................................... 12 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................. 14 To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) ........................................ 14 To All Non-state Armed Groups.......................................................................... 17 To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China ............... 18 To the Government of Thailand.......................................................................... 18 To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)....................... 18 To UNICEF ........................................................................................................ -

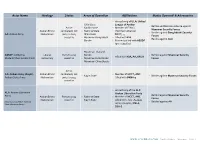

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma)

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Watchlist Mission Statement The Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict strives to end violations against children in armed conflicts and to guarantee their rights. As a global network, Watchlist builds partnerships among local, national and international nongovernmental organizations, enhancing mutual capacities and strengths. Working together, we strategically collect and disseminate information on violations against children in conflicts in order to influence key decision-makers to create and implement programs and policies that effectively protect children. Watchlist works within the framework of the provisions adopted in Security Council Resolutions 1261, 1314, 1379, 1460, 1539 and 1612, the principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and its protocols and other internationally adopted human rights and humanitarian standards. General supervision of Watchlist is provided by a Steering Committee of international nongovernmental organizations known for their work with children and human rights. The views presented in this report do not represent the views of any one organization in the network or the Steering Committee. For further information about Watchlist or specific reports, or to share information about children in a particular conflict situation, please contact: [email protected] www.watchlist.org Photo Credits Cover Photo: UNICEF/NYHQ2006- 1870/Robert Few Please Note: The people represented in the photos in this report are not necessarily themselves victims or survivors of human rights violations or other abuses. No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Notes on Methodology . Information contained in this report is current through January 1, 2009. -

Developing History Curricula to Support Multi-Ethnic Civil Society Among Burmese Refugees and Migrants

NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Research Paper No. 139 Developing history curricula to support multi-ethnic civil society among Burmese refugees and migrants Rosalie Metro E-mail : [email protected] December 2006 Policy Development and Evaluation Service Policy Development and Evaluation Service United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees P.O. Box 2500, 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.unhcr.org These papers provide a means for UNHCR staff, consultants, interns and associates, as well as external researchers, to publish the preliminary results of their research on refugee-related issues. The papers do not represent the official views of UNHCR. They are also available online under ‘publications’ at <www.unhcr.org>. ISSN 1020-7473 Introduction What children learn about history is widely recognized to influence their perceptions and behavior, yet little attention has been given to how to design history curricula for young people in conflict or post-conflict situations. This paper discusses possibilities for development of history curricula that can support multi-ethnic civil society among Burmese refugees, exiles, migrants, and ethnic nationals.1 The paper is adapted from the Master’s thesis I completed in 2003. The research presented here was conducted in February and March of 2003 in Chiang Mai, Mae Sot, Bangkok, and Mae Hong Son, Thailand. Using an action research methodology and an interview guide approach, I investigated history curricula currently in use in refugee camps along the Thai-Burma border, in Burmese-run schools in Thailand, and areas controlled by ethnic nationality groups inside Burma, including ceasefire areas. I then evaluated strategies for redesigning these curricula. -

Report Administration of Burma

REPORT ON THE ADMINISTRATION OF BURMA FOR THE YEAR 1933=34 RANGOON SUPDT., GOVT. PRINTING AND STATIONERY, BURMA 1935 LIST OF AGENTS FOR THE SALE~OF GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN BURMA. AllERICAN BAPTIST llIISSION PRESS, Rangoon. BISWAS & Co., 226 Lewis Street, Rangoon. BRITISH BURMA PRESS BRANCH, Rangoon .. ·BURMA BOO!, CLUB, LTD., Poat Box No. 1068, Rangoon. - NEW LIGHT 01' BURlL\ Pl?ESS, 61 Sule Pagoda Road, Rangoon. PROPRIETOR, THU DHA!IIA \VADI PRE,S, 16-80 lliaun!l :m,ine Street. Rangoon. RANGOOX TIMES PRESS, Rangoon. THE CITY BOOK CLUB, 98 Phayre Street, Rangoon . l\IESSRS, K. BIN HOON & Soi.:s, Nyaunglebin. MAUNG Lu GALE, Law Book Depot, 42 Ayo-o-gale. Manrlalay. ·CONTINENTAL TR.-\DDiG co.. No. 353 Lower Main Road. ~Ioulmein. lN INDIA. BOOK Co., Ltd., 4/4A College Sq<1are, Calcutta. BUTTERWORTH & Co. Undlal, "Ltd., Calcutta . .s. K. LAHIRI & Co., 56 College Street, Calcutta. ,v. NEWMAN & Co., Calcutta. THACKER, SPI:-K & Co., Calcutta, and Simla. D. B. TARAPOREVALA, Soxs & Co., Bombay. THACKER & Co., LTD., Bombay. CITY BOO!! Co., Post Box No. 283, l\Iadras. H!GGINBOTH.UI:& Co., Madras. ·111R. RA~I NARAIN LAL, Proprietor, National1Press, Katra.:Allahabad. "MESSRS. SAllPSON WILL!A!II & Co., Cawnpore, United Provinces, IN }j:URUPE .-I.ND AMERICA, -·xhc publications are obtainable either ~direct from THE HIGH COMMISS!Oli:ER FOR INDIA, Public Department, India House Aldwych, London, \V.C. 2, or through any bookseller. TABLE OF CONTENTS. :REPORT ON THE ADMINISTRATION OF BURMA FOR THE YEAR 1933-34. Part 1.-General Summary. Part 11.-Departmental Chapters. CHAPTER !.-PHYSICAL AND POLITICAT. GEOGRAPHY. "PHYSICAL-- POLITICAL-co11clcl. -

Refugees from Burma Acknowledgments

Culture Profile No. 21 June 2007 Their Backgrounds and Refugee Experiences Writers: Sandy Barron, John Okell, Saw Myat Yin, Kenneth VanBik, Arthur Swain, Emma Larkin, Anna J. Allott, and Kirsten Ewers RefugeesEditors: Donald A. Ranard and Sandy Barron From Burma Published by the Center for Applied Linguistics Cultural Orientation Resource Center Center for Applied Linguistics 4646 40th Street, NW Washington, DC 20016-1859 Tel. (202) 362-0700 Fax (202) 363-7204 http://www.culturalorientation.net http://www.cal.org The contents of this profile were developed with funding from the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, United States Department of State, but do not necessarily rep- resent the policy of that agency and the reader should not assume endorsement by the federal government. This profile was published by the Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL), but the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of CAL. Production supervision: Sanja Bebic Editing: Donald A. Ranard Copyediting: Jeannie Rennie Cover: Burmese Pagoda. Oil painting. Private collection, Bangkok. Design, illustration, production: SAGARTdesign, 2007 ©2007 by the Center for Applied Linguistics The U.S. Department of State reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use, and to authorize others to use, the work for Government purposes. All other rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to the Cultural Orientation Resource Center, Center for Applied Linguistics, 4646 40th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016. -

Languages of Myanmar

Ethnologue report for Myanmar Page 1 of 20 Languages of Myanmar [See also SIL publications on the languages of Myanmar.] Union of Myanmar, Pyeidaungzu Myanma Naingngandaw. Formerly Burma. 42,720,196. Speakers of Tibeto-Burman languages: 28,877,000 or 78% of the population, Daic languages 2,778,900 or 9.6%, Austro- Asiatic languages 1,934,900 or 6.7%, Hmong-Mien languages 6,000 (1991 J. Matisoff). National or official language: Burmese. Literacy rate: 66% to 78%; 78.5% over 15 years old (1991). Also includes Eastern Tamang, Geman Deng, Iu Mien, Malay (21,000), Sylheti, Chinese (1,015,000), people from Bangladesh and India (500,000). Information mainly from F. Lebar, G. Hickey, J. Musgrave 1964; A. Hale 1982; B. Comrie 1987; R. B. Jones 1988; J. Matisoff et al. 1996; D. Bradley 1997; R. Burling ms. (1998). Blind population: 214,440. Deaf population: 2,684,514. Deaf institutions: 1. The number of languages listed for Myanmar is 109. Of those, 108 are living languages and 1 is extinct. Living languages Achang [acn] 1,700 in Myanmar (1983). West of the Irrawaddy River in Katha District, near Banmauk, scattered among the Lashi. Along the China border. Alternate names: Anchan, Chung, Atsang, Acang, Ngac'ang, Ngachang, Ngochang, Mönghsa, Tai Sa'. Dialects: Maingtha. Classification: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto- Burman, Lolo-Burmese, Burmish, Northern More information. Akha [ahk] 200,000 in Myanmar (1991 UBS). Population total all countries: 449,261. Eastern part of Kengtung Shan State. Also spoken in China, Laos, Thailand, Viet Nam. Alternate names: Kaw, Ekaw, Ko, Aka, Ikaw, Ak'a, Ahka, Khako, Kha Ko, Khao Kha Ko, Ikor, Aini, Yani. -

Myanmar Languages | Ethnologue

7/24/2016 Myanmar Languages | Ethnologue Myanmar LANGUAGES Akeu [aeu] Shan State, Kengtung and Mongla townships. 1,000 in Myanmar (2004 E. Johnson). Status: 5 (Developing). Alternate Names: Akheu, Aki, Akui. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Ngwi-Burmese, Ngwi, Southern. Comments: Non-indigenous. More Information Akha [ahk] Shan State, east Kengtung district. 200,000 in Myanmar (Bradley 2007a). Total users in all countries: 563,960. Status: 3 (Wider communication). Alternate Names: Ahka, Aini, Aka, Ak’a, Ekaw, Ikaw, Ikor, Kaw, Kha Ko, Khako, Khao Kha Ko, Ko, Yani. Dialects: Much dialectal variation; some do not understand each other. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Ngwi-Burmese, Ngwi, Southern. More Information Anal [anm] Sagaing: Tamu town, 10 households. 50 in Myanmar (2010). Status: 6b (Threatened). Alternate Names: Namfau. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Sal, Kuki-Chin-Naga, Kuki-Chin, Northern. Comments: Non- indigenous. Christian. More Information Anong [nun] Northern Kachin State, mainly Kawnglangphu township. 400 in Myanmar (2000 D. Bradley), decreasing. Ethnic population: 10,000 (Bradley 2007b). Total users in all countries: 450. Status: 7 (Shifting). Alternate Names: Anoong, Anu, Anung, Fuchve, Fuch’ye, Khingpang, Kwingsang, Kwinp’ang, Naw, Nawpha, Nu. Dialects: Slightly di㨽erent dialects of Anong spoken in China and Myanmar, although no reported diഡculty communicating with each other. Low inherent intelligibility with the Matwang variety of Rawang [raw]. Lexical similarity: 87%–89% with Anong in Myanmar and Anong in China, 73%–76% with T’rung [duu], 77%–83% with Matwang variety of Rawang [raw]. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Central Tibeto-Burman, Nungish. Comments: Di㨽erent from Nung (Tai family) of Viet Nam, Laos, and China, and from Chinese Nung (Cantonese) of Viet Nam.