BURMA (MYANMAR) COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945- )

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945 - ) Major Events in the Life of a Revolutionary Leader All terms appearing in bold are included in the glossary. 1945 On June 19 in Rangoon (now called Yangon), the capital city of Burma (now called Myanmar), Aung San Suu Kyi was born the third child and only daughter to Aung San, national hero and leader of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) and the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), and Daw Khin Kyi, a nurse at Rangoon General Hospital. Aung San Suu Kyi was born into a country with a complex history of colonial domination that began late in the nineteenth century. After a series of wars between Burma and Great Britain, Burma was conquered by the British and annexed to British India in 1885. At first, the Burmese were afforded few rights and given no political autonomy under the British, but by 1923 Burmese nationals were permitted to hold select government offices. In 1935, the British separated Burma from India, giving the country its own constitution, an elected assembly of Burmese nationals, and some measure of self-governance. In 1941, expansionist ambitions led the Japanese to invade Burma, where they defeated the British and overthrew their colonial administration. While at first the Japanese were welcomed as liberators, under their rule more oppressive policies were instituted than under the British, precipitating resistance from Burmese nationalist groups like the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL). In 1945, Allied forces drove the Japanese out of Burma and Britain resumed control over the country. 1947 Aung San negotiated the full independence of Burma from British control. -

Migration from Bengal to Arakan During British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin

Occasional Paper Series Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin 2019 Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher Brussels This and other publications in TOAEP’s Occasional Paper Series may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site http://toaep.org, which uses Persistent URLs for all publications it makes available (such PURLs will not be changed). This publication was first published on 6 December 2019. © Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2019 All rights are reserved. You may read, print or download this publication or any part of it from http://www.toaep.org/ for personal use, but you may not in any way charge for its use by others, directly or by reproducing it, storing it in a retrieval system, transmitting it, or utilising it in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, in whole or in part, without the prior permis- sion in writing of the copyright holder. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the copyright holder. You must not circulate this publication in any other cover and you must impose the same condition on any ac- quirer. You must not make this publication or any part of it available on the Internet by any other URL than that on http://www.toaep.org/, without permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-82-8348-150-1. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 2 2. Setting the Scene: The 1911, 1921 and 1931 Censuses of British Burma ............................ -

Ethnic Armed Actors and Justice Provision in Myanmar

Ethnic Armed Actors and Justice Provision in Myanmar Brian McCartan and Kim Jolliffe October 2016 Preface As a result of decades of ongoing civil war, large areas of Myanmar remain outside government rule, or are subject to mixed control and governance by the government and an array of ethnic armed actors (EAAs). These included ethnic armed organizations, with ceasefires or in conflict with the state, as well as state-backed ethnic paramilitary organizations, such as the Border Guard Forces and People’s Militia Forces. Despite this complexity, order has been created in these areas, in large part through customary justice mechanisms at the community level, and as a result of justice systems administered by EAAs. Though the rule of law and the workings of Myanmar’s justice system are receiving increasing attention, the role and structure of EAA justice systems and village justice remain little known and therefore, poorly understood. As such, The Asia Foundation is pleased to present this research on justice provision and ethnic armed actors in Myanmar, as part of the Foundation’s Social Services in Contested Areas in Myanmar series. The study details how the village, and village-based mechanisms, are the foundation of stability and order for civilians in most of these areas. These systems have then been built through EAA justice systems, which maintain a hierarchy of courts above the village level. Understanding the continuity and stability of these village systems, and the heterogeneity of the EAA justice systems which work alongside them, is essential for understanding civilians’ experiences of justice and security across Myanmar, as well as the opportunities for positive change that exist in Myanmar’s ongoing peace process and governance reforms. -

Burma, Siam (Thailand), and the Philippines in World War Two History and Film

Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal – Vol.5, No.6 Publication Date: June. 25, 2018 DoI:10.14738/assrj.56.4635. Derrah, R. (2018). Hidden Casualties: Burma, Siam (Thailand), and the Philippines in World War Two History and Film. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 5(6) 43-53. Hidden Casualties: Burma, Siam (Thailand), and the Philippines in World War Two History and Film Rick Derrah ABSTRACT This paper examines the World War Two in Burma, Siam (Thailand), and the Philippines and the reflection of .that history within films produced during the same time period. War films were produced all three of these countries during the war period, but, in general, focus almost exclusively on American or British characters as the heroes. There is also very little content dealing with the casualties suffered by the indigenous populations of these countries during the war. Keywords: History; World War Two; Film INTRODUCTION In society popular culture often shapes the perception of the past. These views of the past are sometimes adjusted to make the story more appealing to the projected audience and with the advent of movies this phenomenon has only accelerated. Theses views build upon and reinforce each other creating constructs which are widely known. Movies are often able to create their own reality by building on these common constructs. The view of the movie becomes the reality for many people and this is problematic because movies and other forms of popular culture are created with agendas beyond simply telling a story. These hidden agendas can be simply the story the version of the story the creator wishes to express or even the motivation to make the work profitable. -

A Case Study for Development of Tradition and Culture of Myanmar People Based on Some Myanmar Traditional Festivals

A Case Study for Development of Tradition and Culture of Myanmar People Based on some Myanmar Traditional Festivals Aye Pa Pa Myo* [email protected] Assistant Lecturer, Department of English, Yangon University of Education, Myanmar Abstract It is generally said that Myanmar is a beautiful country situated on the land of Southeast Asia and it is also a land of traditional festivals which has the collection of tradition and culture. This paper has an attempt to observe the development of tradition and culture of Myanmar People based on some Myanmar Traditional Festivals. The research was done with analytical approach. It took three months. self-observation, questionnaires, taking photos, and interviewing were used as the research tools. Data were analyzed with the qualitative and quantitative methods. In accordance with the findings, it can be clearly seen that the majority of Myanmar enjoy maintaining and admiring their tradition and culture, assisting others as much as they can, hospitalizing the others, particularly, foreigners. Their inspiration can influence the tourists, as well as Myanmar Traditional Festivals can reveal the lovely and beautiful Myanmar Tradition and Culture. Therefore, the Republic of the Union of Myanmar can be called the Land of Culture to the great extent. In brief, the findings from the research will support to further research related to observing dynamic development of Aspects of Myanmar. Key Terms- tradition and culture Introduction Our Country, the Republic of the Union of Myanmar situated on the Indochina Peninsula in South East Asia is well-known as “the Golden Land” because of its glittering pagodas, vast tract of timber forests, huge mineral resources, wonderful historical sites and monuments and the hospitality of Myanmar People. -

A Semantic Study of Taste-Related Words in the Myanmar Language

Dagon University Research Journal 2014, Vol. 6 Religious Beliefs of Shan-Gyi National Live in Ae-Nai Village, Lashio Township, Shan State in Myanmar Kay Thi Thant* Abstract This study explored how to maintain Drum Ensemble (“saing wain:” in Myanmar) as Myanmar cultural heritage. The paper described especially relationship between spirit propitiation ceremony (“nat pwe” in Myanmar) and drum ensemble. Yangon Region is presumed to be the most developed place in the country that it could be very much liable to any infiltration of foreign culture and music. But fortunately, it was found that Big Drum Ensemble is still being used in some downtown areas and some adjacent area in Yangon region. Therefore, study sites were chosen some wards and villages of some Townships in Yangon Region to collect information and data regarding with the usage of drum ensemble. The three studied groups of the community were divided as follows: (1) The drum ensemble members of musicians whose livelihoods depend solely upon Bamar drum ensemble (2) appropriation ceremony (“na´ kana:” in Myanmar) professionals consisted of a woman or a sissy said to be chosen as consort by a spirit (spirit medium) (“na´ gado” in Myanmar), a leader of spirit medium (“kana: si:” in Myanmar), and other followers and (3) the audience. Then the audience comprised the doers and related persons, people who sponsored expenditure of ritual event (“kana: pwe:” in Myanmar) and people who come to watch entertainment. Again it could be classified two categories of audiences who came and watched drum ensemble entertainment. The first said to be the ones who are coming to watch according to their hobby who watch and listen with artistic ears and the remaining groups represent the ones who come and see just for fun. -

Burma Is Founded and Buddhism Is Adopted

2007 - The junta adds a year to Suu Kyi’s house Timeline arrest. In reaction to the unexpected rise in fuel costs, 1057 - Burma is founded and Buddhism is adopted. Buddhist monks lead anti-government protests. The 1885 - Burma is annexed to British India. government kills 13 protestors and arrests thousands 1937-1948 - Burma is a colony of the British crown. of monks in the Saffron Revolution. 1942 - Japan invades and occupies Burma using the 2008 - The proposed constitution ensures a quarter of Japanese-trained Burma Independence Army, which parliament seats to the military and bans Aung San later becomes the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom Suu Kyi from running for office. Cyclone Nargis kills as League (AFPFL). many as 134,000. The government claims 92% voted 1945 - General Aung San leads the AFPFL and frees in favor of a referendum on the constitution despite Burma from Japan with help from the British. the humanitarian crisis of the cyclone. Aung San Suu 1947 - General Aung San and members of his Kyi’s house arrest is renewed. Activists receive government are assassinated by nationalist rival U Saw. sentences up to 65 years in closed trials. 1958-1960 - AFPFL party splits, resulting in the 2009 - Burma denies the existence of the Muslim formation of a caretaker government. Rohingya minority. Talks between the military junta 1960 - U Nu wins elections. His endorsement of and Suu Kyi begin again. Burma Buddhism and acceptance of separatism antagonizes 2010 - Election laws pass allowing the electoral the military. commission to be picked by junta. NLD plans to 1962 - Military coup led by General Ne Win abolishes boycott polls, but the National Democratic Front (NDF) the federal system and implements the “Burmese Way gains legal status and plans to run in elections. -

Sold to Be Soldiers the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

October 2007 Volume 19, No. 15(C) Sold to be Soldiers The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Terminology and Abbreviations................................................................................2 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 The Government of Burma’s Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw ..................................6 Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment ...............................................9 Non-state Armed Groups....................................................................................11 The Local and International Response ............................................................... 12 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................. 14 To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) ........................................ 14 To All Non-state Armed Groups.......................................................................... 17 To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China ............... 18 To the Government of Thailand.......................................................................... 18 To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)....................... 18 To UNICEF ........................................................................................................ -

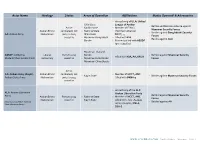

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

Myanmar (Formerly Burma) Pronounce Its Name Correctly (MEE-Ah-Mah) and You’Ll Be Sure to Impress the Locals!

Myanmar (formerly Burma) Pronounce its name correctly (MEE-ah-mah) and you’ll be sure to impress the locals! Note: Myanmar is still a country in transition as it opens up to more foreign visitors, and so travel information to the country is quite changeable. Visas Tourist visas are single entry only and allow you to stay in Myanmar for 28 days. They have to be used within a 90-day window after they are issued. You always need a visa in advance of coming to Myanmar. The visa fee is $20. You can apply for the visas online through the Myanmar Embassy’s website, which has more information about visa requirements (http://www.mewashingtondc.com/visa_form_1_en.php). Climate The climate in Myanmar varies depending on elevation, but most of the country is considered tropical or subtropical. There are three distinct seasons: Cold dry season November - February 68° - 75° F Hot dry season March - April 86° - 95° F Hot wet season May - October 77° - 86° F From June to August, rainfall can be constant for long periods of time, particularly on the Bay of Bengal coast, and in Yangon and the Irrawaddy Delta. The rain is less intense in September and October. For these reasons, more tourists travel to Myanmar during the cold dry season. During those months, accommodations are more limited and potentially more expensive. Try booking ahead to avoid paying high prices for last-minute rooms. The hot muggy weather keeps many tourists away in other seasons, making some prices lower and accommodations easier to come by. As a general rule, temperatures and humidity become lower at higher altitudes. -

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma)

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Watchlist Mission Statement The Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict strives to end violations against children in armed conflicts and to guarantee their rights. As a global network, Watchlist builds partnerships among local, national and international nongovernmental organizations, enhancing mutual capacities and strengths. Working together, we strategically collect and disseminate information on violations against children in conflicts in order to influence key decision-makers to create and implement programs and policies that effectively protect children. Watchlist works within the framework of the provisions adopted in Security Council Resolutions 1261, 1314, 1379, 1460, 1539 and 1612, the principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and its protocols and other internationally adopted human rights and humanitarian standards. General supervision of Watchlist is provided by a Steering Committee of international nongovernmental organizations known for their work with children and human rights. The views presented in this report do not represent the views of any one organization in the network or the Steering Committee. For further information about Watchlist or specific reports, or to share information about children in a particular conflict situation, please contact: [email protected] www.watchlist.org Photo Credits Cover Photo: UNICEF/NYHQ2006- 1870/Robert Few Please Note: The people represented in the photos in this report are not necessarily themselves victims or survivors of human rights violations or other abuses. No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Notes on Methodology . Information contained in this report is current through January 1, 2009. -

Refugees from Burma Acknowledgments

Culture Profile No. 21 June 2007 Their Backgrounds and Refugee Experiences Writers: Sandy Barron, John Okell, Saw Myat Yin, Kenneth VanBik, Arthur Swain, Emma Larkin, Anna J. Allott, and Kirsten Ewers RefugeesEditors: Donald A. Ranard and Sandy Barron From Burma Published by the Center for Applied Linguistics Cultural Orientation Resource Center Center for Applied Linguistics 4646 40th Street, NW Washington, DC 20016-1859 Tel. (202) 362-0700 Fax (202) 363-7204 http://www.culturalorientation.net http://www.cal.org The contents of this profile were developed with funding from the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, United States Department of State, but do not necessarily rep- resent the policy of that agency and the reader should not assume endorsement by the federal government. This profile was published by the Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL), but the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of CAL. Production supervision: Sanja Bebic Editing: Donald A. Ranard Copyediting: Jeannie Rennie Cover: Burmese Pagoda. Oil painting. Private collection, Bangkok. Design, illustration, production: SAGARTdesign, 2007 ©2007 by the Center for Applied Linguistics The U.S. Department of State reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use, and to authorize others to use, the work for Government purposes. All other rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to the Cultural Orientation Resource Center, Center for Applied Linguistics, 4646 40th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016.