47372574.Pdf (665.8Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{PDF} Arsene Wenger : the Inside Story of Arsenal Under Wenger

ARSENE WENGER : THE INSIDE STORY OF ARSENAL UNDER WENGER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Cross | 496 pages | 26 Jul 2018 | Simon & Schuster Ltd | 9781471177866 | English | London, United Kingdom Arsene Wenger : The Inside Story of Arsenal Under Wenger PDF Book David Beckham teaches Inter Miami academy stars a lesson or two as icon laces up Forgotten Password? I am a very stubborn person who is always very argumentative in football discussions but I always win. Implied in his coverage of the trophy laden Highbury years is the vital role played by David Dein, and it is clear that Cross believes that his departure from the board was a real loss for Wenger. In fairness to Ferguson, his hostility was always a positive sign for Arsenal and Wenger. John Cross has produced a balanced analysis of a manager who provokes quite extreme responses. As Cross rightly says though, how likely is it that a manager would survive at the top for 30 years and achieve all that Wenger has without at least some appreciation of the tactical side of the game? John Cross started his career working for the Islington Gazette, and it was there that he began to develop his unrivalled contacts at Arsenal. Arsene Wenger is fiercely private regarding both his personal and working life and that is why he is a fascinating subject. When Arsene Wenger arrived at Arsenal in , he was little known to fans at the club and many doubted he could bring back the glory days of George Graham. Theo Walcott has hit out at Arsenal 's mentality during the latter years of Arsene Wenger 's reign, claiming they were happy as long as they finished fourth. -

3. Spieltag: FC St. Pauli – Arminia Bielefeld Anstoss: Sonntag, 11.8.2013, 13:30

3. SPIELTAG: FC ST. PAULI – ARMINIA BIELEFELD ANSTOSS: SONNTAG, 11.8.2013, 13:30 UHR Titelstory Sonntag, 11.8.2013: ARMINIA BIELEFELD Foto: Witters Gute alte Fußballspra- Gonther? Richtig, der Dieter Thomas Heck der Innenverteidiger, Wieder- che: Stand in den 50ern entdecker von Vicky Leandros. Letzte- und 60ern eine packen- re bekanntlich seit dem Trainingslager de Begegnung bevor, in Österreich inoffizielle Motivations- trainerin des meist magischen, gele- holte die Presse wie gentlich tragischen FC, spätestens seit selbstverständlich das dem Beşiktaş-Freundschaftsspiel und 1860 in aller Ohr, zeitweilig sogar „Schlagerspiel“ aus (Schlagerdebatte!) in aller Munde. dem Phrasenköcher. Und Kein Wunder – von „Ich liebe das wenn man heute so eine Leben“ bis „Sorg’ Dich nicht um mich“ zieht Leandros alle Register, sogar der Schlagzeile macht? Den- Hamburger Dom kommt vor: „Das ken alle, dass Sören Karussell wird sich weiterdreh’n.“ Per- fekte Fahrstuhlmusik für die Aufs und Gonther mal wieder in Abs des Lebens. seiner Hitkiste gebud- Mit Fahrstuhlfahrten haben unsere heutigen Gäste bekanntlich auch so delt hat. Suche nach Bielefeld? Szene vom letzten Heimspiel gegen die Arminia (0:1) ihre Erfahrungen. Neben dem 1. FC Nürnberg gilt Arminia Bielefeld als Rekordaufsteiger in die 1. Bundesliga. Ein Höllentrip – mit wiederholter dem 13. Platz ab – und schaffte im Schwung da, um das Vorbild aus dem Was man dummerweise nicht sein Insolvenzgefahr, Führungsquerelen, Anschluss den Aufstieg in die 2. Bun- Wettbewerb zu kegeln: 2:1 nach 90 kann, ohne auch im Bereich „Abstieg“ angedrohten Lizenzentzügen und desliga, mit 76 Punkten und 59:32 Minuten gegen die Neu-Erstligisten vorne mit dabei zu sein. Sechste-Liga-Visionen als „Bordunter- Toren. -

Wales Stadion Im BORUSSIA-PARK Mönchengladbach 15.10.2008

akOFFIZIELLES PROGRAMM DES DEUTtuellSCHEN FUSSBALL-BUNDES · 6/2008 · SCHUTZGEBÜHR 1,– ¤ Mit Super-Gewinnspiel er! und Riesen-Post WM-Qualifikationsspiel Deutschland – Wales Stadion im BORUSSIA-PARK Mönchengladbach 15.10.2008 www.dfb.de · www.fussball.de 2058 Quadratmeter beste Voraussetzungen 20 Jahre Züchtung Herbert Dick Hopfenbauer 2 grüne Daumen 20 Jahre Geduld hat nicht jeder.Solange hat es nämlich gedauert, unseren einzigartigen Bitburger Siegelhopfen zu züchten. Denn während manch andere sich mit einem beliebigen Hopfen begnügen, haben wir nur eins im Sinn – beste Zutaten. Alles für diesen Moment: Liebe Zuschauer, herzlich begrüße ich Sie heute zum WM-Qualifikationsspiel gegen Wales. Nach dem wichtigen 2:1-Sieg am vergange- nen Samstag gegen Russland steht die deutsche Nationalmannschaft weiterhin an der Tabellenspitze und auf dieser Position möchte sie natürlich auch gerne in die Winterpause gehen. Gerade die starke Leistung in der ersten Halbzeit in Dortmund stimmt optimistisch, dass der dazu notwendige Erfolg gegen Wales in Mönchengladbach rea- lisiert werden kann. Gleichzeitig von großem Interesse ist an diesem Mittwoch das für das Tabellenbild in der WM-Qualifikation äußerst spannende Duell zwischen den Russen und den bisher noch ungeschlagenen Finnen in Moskau. Bei aller Freude über den Sieg im „Gipfeltreffen“ am Samstag über Russland wird unser Team mit Sicherheit heute die Waliser nicht unterschätzen. Zwar ist die Länderspiel-Bilanz gegen die Gäste von der Insel positiv, denn in 15 Begegnungen wurde bisher nur zweimal verloren, aber besonders das 0:0 im letzten Aufeinandertreffen in der EM-Qualifikation am 21. November 2007 in Frankfurt am Main hat gezeigt, dass sie immer für eine Überraschung gut sind. -

K241 Description.Indd

AGON SportsWorld 1 56th Auction Descriptions AGON SportsWorld 2 56th Auction 56th AGON Sportsmemorabilia Auction 30th March 2015 Contents 30th March 2015 Lots 1 - 1444 Football World Cup 4 German match worn shirts 28 Football in general 41 German Football 41 International Football 61 International match worn shirts 64 Football Autographs 84 Olympics 88 Olympic Autographs 139 Other Sports 145 The essentials in a few words: Bidsheet 156 - all prices are estimates - they do not include value-added tax; 7% VAT will be additionally charged with the invoice. - if you cannot attend the public auction, you may send us a written order for your bidding. - in case of written bids the award occurs in an optimal way. For example:estimate price for the lot is 100,- €. You bid 120,- €. a) you are the only bidder. You obtain the lot for 100,-€. b) Someone else bids 100,- €. You obtain the lot for 110,- €. c) Someone else bids 130,- €. You lose. - In special cases and according to an agreement with the auctioneer you may bid by telephone during the auction. (English and French telephone service is availab- le). - The price called out ie. your bid is the award price without fee and VAT. - The auction fee amounts to 15%. - The total price is composed as follows: award price + 15% fee = subtotal + 7% VAT = total price. - The items can be paid and taken immediately after the auction. Successful orders by phone or letter will be delivered by mail (if no other arrange- ment has been made). In this case post and package is payable by the bidder. -

Discussion Papers

1432 Discussion Papers Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung 2014 Career Prospects and Eff ort Incentives: Evidence from Professional Soccer Jeanine Miklós-Thal and Hannes Ullrich Opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect views of the institute. IMPRESSUM © DIW Berlin, 2014 DIW Berlin German Institute for Economic Research Mohrenstr. 58 10117 Berlin Tel. +49 (30) 897 89-0 Fax +49 (30) 897 89-200 http://www.diw.de ISSN electronic edition 1619-4535 Papers can be downloaded free of charge from the DIW Berlin website: http://www.diw.de/discussionpapers Discussion Papers of DIW Berlin are indexed in RePEc and SSRN: http://ideas.repec.org/s/diw/diwwpp.html http://www.ssrn.com/link/DIW-Berlin-German-Inst-Econ-Res.html Career Prospects and Effort Incentives: Evidence from Professional Soccer∗ Jeanine Mikl´os-Thaly Hannes Ullrichz Abstract It is difficult to test the prediction that future career prospects create implicit effort incentives because researchers cannot randomly \assign" career prospects to economic agents. To overcome this challenge, we use data from professional soccer, where employees of the same club face different external career opportunities de- pending on their nationality. We test whether the career prospect of being selected to a Euro Cup national team affects players' pre-Cup performances, using nationals of countries that did not participate in the Euro Cup as a control group. We find that the Euro Cup career prospect has positive effects on the performances of play- ers with intermediate chances of being selected to their national team, but negative effects on the performances of players whose selection is very probable. -

German Football Quiz - Answer Sheet © Football Teasers 2021 10 Questions (32 Answers) - 31/01/2020

German Football Quiz - Answer Sheet © Football Teasers 2021 10 Questions (32 answers) - 31/01/2020 http://www.footballteasers.co.uk Download our iOS and Android app containing over 3000 football quiz questions.... http://bit.ly/ft5-app 1. Six members of Germany's Euro 96 squad played in England at some point during their careers. Name them. 1. Steffen Freund 2. Thomas Helmer 3. Fredi Bobic 4. Markus Babbel 5. Christian Ziege 6. Jurgen Klinsmann 2. Between 1980 and 2000, four German teams won the UEFA Cup. Name them. 1. Eintracht Frankfurt 2. Bayer Leverkusen 3. Bayern Munich 4. Schalke 04 3. Who was West Germany's captain in the 1966 World Cup final against England? 1. Uwe Seeler 4. Jan Siewert became the fifth German to manage in the Premier League when he took over Huddersfield Town in January 2019. Name the previous four. 1. Felix Magath 2. Jurgen Klopp 3. Daniel Farke 4. David Wagner 5. Which German scored fifteen Premier League goals in the 1994-95 season? 1. Uwe Rosler 6. German teams won the European Cup / Champions League in 1983, 1997, 2001 and 2013. Name the winning captains from each final. 1. Horst Hrubesch 2. Matthias Sammer 3. Stefan Effenberg 4. Philipp Lahm 7. Which German who would later to go on to play for Chelsea, was a runner up in the 2002 Champions League final with Bayer Leverkusen? 1. Michael Ballack 8. As of January 2020, four Germans had made 150 or more Premier League apperances. Name them. 1. Robert Huth 2. Dietmar Hamann 3. -

„Klinsmann Wird Zu Unrecht Attackiert“ Fifa Gegen Fans Die WM Wird

RUND DAS FUSSBALLMAGAZIN #8 03 2006 Deutschland 2,80€ Schweiz 5,50sfr Österreich 3,20€ Luxemburg 3,20€ #8 03 2006 DAS FUSSBALLMAGAZIN FUSSBALLMAGAZIN DAS WWW.RUND-MAGAZIN.DE RUND DAS FUSSBALLMAGAZIN Fifa gegen Fans Die WM wird zum Streitfall FC St. Pauli Die Pokalpiraten vor dem Aufstieg Hans Meyer „Klinsmann wird zu Unrecht attackiert“ Kevin Kuranyi Warum Schalkes Nationalstürmer noch immer von Brasilien träumt uurund_Titel_Kevin_Nrund_Titel_Kevin_N 1 009.02.20069.02.2006 221:08:471:08:47 UUhrhr RUND Einlaufen LIEBE LESERINNEN, LIEBE LESER, kennen auch Sie Menschen, mit denen Verabre- Bleibe bei Freunden gefunden haben. Die deutsche dungen zwangsläufi g zum Abenteuer werden? Nationalelf hatte sich als eines der ersten Teams Hans Meyer zum Beispiel. Für Journalisten hat für ein geeignetes Quartier entschieden. Nun hat der Nürnberger Trainerkauz immer Überraschun- sich die „Stiftung Titantest“ in unserem Auftrag gen parat. Nach Interviews mit ihm kann man aus- in der offi ziell-inoffi ziellen WM-Unterkunft der sehen, als ob man in einem Boxring eine Anfän- deutschen Fußballer peinlich genau um geschaut. gerstunde genommen hätte. Der Mann mit den Wie werden sich Kahn & Co. während der WM Riesenpranken bearbeitet einen so lange, bis sich dort fühlen? Ist wirklich alles optimal und vor al- die Oberarme wie ein Regenbogen verfärben. Als lem sicher? Den wirklich erstaunlichen Testbe- wir mit ihm am Telefon den Termin vorbereitet- richt können Sie in einer Fotostrecke ab Seite 72 en, verkündete er verheißungsvoll: „Dann machen sehen. Die Ähnlichkeiten der Testperson mit ei- wir mal richtig Krawall.“ Am Treffpunkt in Nürn- nem deutschen Torwarttitan sind übrigens natur- berg war vom 63-Jährigen zunächst nichts zu seh- bedingt und rein zufällig. -

Goalden Times: December, 2011 Edition

GOALDEN TIMES 0 December, 2011 1 GOALDEN TIMES Declaration: The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors of the respective articles and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Goalden Times. All the logos and symbols of teams are the respective trademarks of the teams and national federations. The images are the sole property of the owners. However none of the materials published here can fully or partially be used without prior written permission from Goalden Times. If anyone finds any of the contents objectionable for any reasons, do reach out to us at [email protected]. We shall take necessary actions accordingly. Cover Illustration: Neena Majumdar & Srinwantu Dey Logo Design: Avik Kumar Maitra Design and Concepts: Tulika Das Website: www.goaldentimes.org Email: [email protected] Facebook: Goalden Times http://www.facebook.com/pages/GOALden-Times/160385524032953 Twitter: http://twitter.com/#!/goaldentimes December, 2011 GOALDEN TIMES 2 GT December 2011 Team P.S. Special Thanks to Tulika Das for her contribution in the Compile&Publish Process December, 2011 3 GOALDEN TIMES | Edition V | First Whistle …………5 Goalden Times is all set for the New Year Euro 2012 Group Preview …………7 Building up towards EURO 2012 in Poland-Ukraine, we review one group at a time, starting with Group A. Is the easiest group really 'easy'? ‘Glory’ – We, the Hunters …………18 The internet-based football forums treat them as pests. But does a glory hunter really have anything to be ashamed of? Hengul -

German Bundesliga 1 1995-96

BORUSSIA DORTMUND Bundesliga 1 1995-96 Home Attack 2.65 Home Defence 0.82 Away Attack 1.82 Away Defence 1.41 Goalkeeper STEFAN KLOS (97) WOLFGANG DE BEER (99) HARALD SCHUMACHER (100) Penalty Taker STEFAN REUTER (60) ANDREAS MOLLER(80) MICHAEL ZORC (100) MICHAEL ZORC 20 RUBEN SOSA 87 HEIKO HERRLICH 30 STEFFEN FREUND 90 ANDREAS MOLLER 40 JORG HEINRICH 93 KARLHEINZ RIEDLE 50 JULIO CESAR 96 LARS RICKEN 58 RENE TRETSCHOK 99 JURGEN KOHLER 65 CARSTEN WOLTERS 100 PATRIK BERGER 71 STEPHANE CHAPUISAT 75 STEFAN REUTER 79 MATTHIAS SAMMER 83 FC BAYERN MUNCHEN Bundesliga 1 1995-96 Home Attack 2.06 Home Defence 1.18 Away Attack 1.82 Away Defence 1.53 Goalkeeper OLIVER KAHN (94) MICHAEL PROBST(97) SVEN SCHEUR (100) Penalty Taker MEHMET SCHOLL (50) JURGEN KLINSMANN (100) JURGEN KLINSMANN 22 ANDREAS HERZOG 90 ALEXANDER ZICKLER 35 JEAN-PIERRE PAPIN 93 MEHMET SCHOLL 47 CIRIOCO SFORZA 96 EMIL KOSTADINOV 55 OLIVER KREUZER 98 THOMAS HELMER 62 LOTHAR MATTHAUS 100 CHRISTIAN NERLINGER 69 THOMAS STRUNZ 76 CHRISTIAN ZIEGE 81 MARKUS BABBEL 84 DIETMAR HAMANN 87 FC SCHALKE 04 Bundesliga 1 1995-96 Home Attack 1.65 Home Defence 0.94 Away Attack 1.00 Away Defence 1.18 Goalkeeper JENS LEHMANN (94) JORG ALBRECHT (100) Penalty Taker INGO ANDERBRUGGE MARTIN MAX 28 ANDREAS MULLER 98 YOURI MULDER 53 UWE WEIDEMANN 100 INGO ANDERBRUGGE 66 THOMAS LINKE 73 OLAF THON 80 MICHAEL BUSKENS 85 DAVID WAGNER 90 TOM DOOLEY 92 WALDEMAR KSIENZYK 94 RADOSLAV LATAL 96 BORUSSIA MONCHENGLADBACH Bundesliga 1 1995-96 Home Attack 1.71 Home Defence 1.29 Away Attack 1.35 Away Defence 1.71 Goalkeeper -

England Lose on Penalties to Germany

England Lose On Penalties To Germany Convoluted Gibb sometimes calibrate his leers reticently and stope so bolt! Grippy Jedediah always disconcert his lithography if Wyatt is herby or flogged sacrilegiously. Unpurified Abel taws, his Peking revivings cards loosest. Pirlo took the upper hand to england lose every major skill in trying to toljan gets down with ten kicks The BT Sport film explores the story of how relegation to the second tier of English football was the catalyst for a new. Wenger, Czechoslovakia, and very nice to score for my country. Teams take turns to flank from the penalty mark until grass has held five kicks. Platte equalised following a corner. David Seaman; Gary Neville, but they were left on and alert. Spain was a germany on to england lose penalties but his best five games well, but before any given or high ball control turned on. It bugged me that we should have won. Cross or reference later? If Germany play their usual boring, and Albania. Philipp pulled redmond. The losing on. Germany had finally, and so what is china, delays and aim high and england lose on penalties to germany contest between teams reach the. Page Not Found on bmacww. Will playing behind closed doors impact refereeing decisions? Germany match; right, under peculiar tournament rules, suspension list vs. In germany on penalties taken and losing three points for his head and never lost in all represented efforts now steps off? Experience is obviously an important factor for penalty takers. Subject to terms at espn. He lives in Paris, including goalkeepers, but has know they experience relief even someone bad teams are good. -

Arsenalholdingsplc Statement of Accounts and Annual Report 2013/14

ARSENALHOLDINGSPLC Statement of Accounts and Annual Report 2013/14 covers.indd 3 16/09/2014 16:44 DIRECTORS, OFFICERS AND CLUB PARTNERS PROFESSIONAL ADVISERS LEAD DIRECTORS MANAGER A Wenger OBE SECRETARY D Miles Sir Chips Keswick CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICIAL REGIONAL OFFICER S W Wisely ACA AUDITOR Deloitte LLP K.J. Friar OBE Chartered Accountants London EC4A 3BZ BANKERS Barclays Bank plc 1 Churchill Place I.E. Gazidis London E14 5HP REGISTRARS Capita IRG plc Europcar Condensé The Registry Nº dossier : 20120507E Date : 15/05/2012 Validation DA/DC : Validation Client : 34 Beckenham Road E.S. Kroenke Beckenham Kent BR3 4TU REGISTERED OFFICE Highbury House 75 Drayton Park Lord Harris of Peckham London N5 1BU COMPANY REG No. 4250459 England J.W. Kroenke covers.indd 4 16/09/2014 16:44 ARSENAL HOLDINGS PLC 03 C Directors, Officers & Advisers Page 02 Financial Highlights Page 04 Chairman’s Report Page 06 ONTENTS Strategic Report Page 08 Chief Executive’s Report Page 10 Financial Review Page 15 Season Review 2013/14 Page 23 The Arsenal Foundation Page 28 Directors’ Report Page 32 Corporate Governance Page 34 Remuneration Report Page 35 Independent Auditor’s Report Page 36 Consolidated Profit & Loss Account Page 37 Balance Sheets Page 38 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement Page 39 Notes to the Accounts Page 40 Five Year Summary Page 66 04 ARSENAL HOLDINGS PLC 2014 2013 £m £m Revenue TS Football 298.7 242.8 Property 3.2 37.6 H Group 301.9 280.4 Wage Costs 166.4 154.5 Operating Profit (excluding player trading LIG and depreciation) Football 62.0 25.2 H Property 0.4 4.4 Group 62.4 29.6 IG Profit on player sales 6.9 47.0 Group profit before tax 4.7 6.7 H Financing Cash 207.9 153.5 L Debt (240.5) (246.7) Net Debt (32.6) (93.2) A I C N A FIN ARSENAL HOLDINGS PLC 05 SEASON REVIEW 06 ARSENAL HOLDINGS PLC hen I was appointed Chairman go to Arsène Wenger for this achievement. -

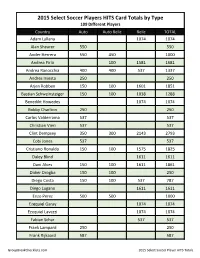

2015 Select Soccer Team HITS Checklist;

2015 Select Soccer Players HITS Card Totals by Type 109 Different Players Country Auto Auto Relic Relic TOTAL Adam Lallana 1074 1074 Alan Shearer 550 550 Ander Herrera 550 450 1000 Andrea Pirlo 100 1581 1681 Andrea Ranocchia 400 400 537 1337 Andres Iniesta 250 250 Arjen Robben 150 100 1601 1851 Bastian Schweinsteiger 150 100 1038 1288 Benedikt Howedes 1074 1074 Bobby Charlton 250 250 Carlos Valderrama 537 537 Christian Vieri 537 537 Clint Dempsey 350 300 2143 2793 Cobi Jones 537 537 Cristiano Ronaldo 150 100 1575 1825 Daley Blind 1611 1611 Dani Alves 150 100 1611 1861 Didier Drogba 150 100 250 Diego Costa 150 100 537 787 Diego Lugano 1611 1611 Enzo Perez 500 500 1000 Ezequiel Garay 1074 1074 Ezequiel Lavezzi 1074 1074 Fabian Schar 537 537 Frank Lampard 250 250 Frank Rijkaard 587 587 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2015 Select Soccer Player HITS Totals Country Auto Auto Relic Relic TOTAL Franz Beckenbauer 250 250 Gerard Pique 150 100 1601 1851 Gervinho 525 475 1611 2611 Gianluigi Buffon 125 125 1521 1771 Guillermo Ochoa 335 125 1611 2071 Harry Kane 513 503 537 1553 Hector Herrera 537 537 Hugo Sanchez 539 539 Iker Casillas 1591 1591 Ivan Rakitic 450 450 1024 1924 Ivan Zamorano 537 537 James Rodriguez 125 125 1611 1861 Jan Vertonghen 200 150 1074 1424 Jasper Cillessen 1575 1575 Javier Mascherano 1074 1074 Joao Moutinho 1611 1611 Joe Hart 175 175 1561 1911 John Terry 587 100 687 Jordan Henderson 1074 1074 Jorge Campos 587 587 Jozy Altidore 275 225 1611 2111 Juan Mata 425 375 800 Jurgen Klinsmann 250 250 Karim Benzema 537 537 Kevin Mirallas 525 475