Five Narratives of Religious

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACCOUNTING to the PEOPLE #Changinglives #Transformingghana H

ACCOUNTING TO THE PEOPLE #ChangingLives #TransformingGhana H. E John Dramani Mahama President of the Republic of Ghana #ChangingLives #TransformingGhana 5 FOREWORD President John Dramani Mahama made a pact with the sovereign people of Ghana in 2012 to deliver on their mandate in a manner that will change lives and transform our dear nation, Ghana. He has been delivering on this sacred mandate with a sense of urgency. Many Ghanaians agree that sterling results have been achieved in his first term in office while strenuous efforts are being made to resolve long-standing national challenges. PUTTING PEOPLE FIRST This book, Accounting to the People, is a compilation of the numerous significant strides made in various sectors of our national life. Adopting a combination of pictures with crisp and incisive text, the book is a testimony of President Mahama’s vision to change lives and transform Ghana. EDUCATION The book is presented in two parts. The first part gives a broad overview of this Government’s performance in various sectors based on the four thematic areas of the 2012 NDC manifesto.The second part provides pictorial proof of work done at “Education remains the surest path to victory the district level. over ignorance, poverty and inequality. This is self evident in the bold initiatives we continue to The content of this book is not exhaustive. It catalogues a summary of President take to improve access, affordability, quality and Mahama’s achievements. The remarkable progress highlighted gives a clear relevance at all levels.” indication of the President’s committment to changing the lives of Ghanaians and President John Dramani Mahama transforming Ghana. -

Agona West Municipal Assembly

AGONA WEST MUNICIPAL ASSEMBLY 2015 ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT (APR) COMPILED BY: MUNICIPAL PLANNING COORDINATING UNIT (MPCU) FEBRUARY, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page District Profile 2 - 13 M & E Activities Report Update on Core Municipal Indications & Targets 14 - 17 Update on Disbursements from Funding Sources 17 - 19 Update on Critical Development and Poverty Issues 19 - 24 Programme/Projects status for the Year 2015 25 1 1. DISTRICT PROFILE 1.1 Establishment Agona West Municipal Assembly (AWMA) was created out of the former Agona District Assembly (ADA) on 25th February, 2008 by LI 1920. AWMA is one of the twenty (20) political and administrative districts in the Central Region of Ghana. AWMA has 1 Urban Council – Nyarkrom Urban Council (LI 1967) and 5 Zonal Councils. 1.2 Vision and Mission Statement 1.2.1 Vision To become a well-developed Municipal Assembly that provides and facilitates excellent services to its people to ensure improvement in the quality of life of its people. 1.2.2 Mission Statement The Agona West Municipal Assembly exists to facilitate the improvement in the quality of life of the people in close collaboration with the private sector and other development partners in the Municipality through the mobilization and the judicious use of resources and provision of Basic Socio-Economic Development within the context of Good Governance. 1.3 Physical Characteristics 1.3.1 Location and Size Agona West is situated in the eastern corner of the Central Region within latitudes 5030’ and 5050’N and between longitudes 0035’ and 0055’W.cIt has a total land area of 447 square kilometers. -

Youth Indevelopment: Workers Brigade and the Young Pioneers 0F Ghana

‘Y:“ W‘-vqu-’ " “hutch-“4‘9; YOUTH INDEVELOPMENT: WORKERS BRIGADE AND THE YOUNG PIONEERS 0F GHANA Thesis-for the Degree of M .u A. MICHlGAN STATE UNIVERSITY I . ‘ .o I o ,. x " vl l .. ."' a.‘ , r u '0 .- l . _ . , - ,1..¢Iv . .1 '5. J.r -I"L" ..- . '4':', a-on. .v .1 V' .l' . "" p v '- rv' H- 4 . y , {o- l o ..l— . H '1’:;_::,'_. J '79}; ' "Ti:- {72" :1 ‘ 4-1’ 3 .’. f" , .v 0‘. ' vl~ , ,.,; fi': {1/ f}; 1" o 2- -r . the "‘“”J'¥gtz‘§‘k“?fif,' ' . 2.09:6. :"’f/.‘ o. a Ila} o .f " In! 5h5". .v' _. , 7 , 4;-, '0 'I ~i;r',"‘¢‘_,,v """.:4- I h" ‘1 ' ’_". .., t ‘0' “t o ‘ ;:f'.Jl, .'I.‘,‘ .i‘o". 'g . 0' - '1’. A. \Hrb.b LI BRAR y 9 University " 'I ' 1‘ - £2. rm... swims av ‘9‘ 1} WM 8 SUNS' ~ BNUK‘MW'“ \w LIBRARY amozns , \ "mam: mam-m ll ~ ABSTRACT YOUTH IN DEVELOPMENT: WORKERS BRIGADE AND THE YOUNG PIONEERS 0F GHANA By Diane Szymkowski The central focus of this thesis is an examination of the relationship between the development of a large, unemployed youth cohort in African cities and the utiliza- tion of the youth sector in national development. Certain consequences of the development of this co- hort in the cities, such as acts of delinquency and riots in the towns, lack of sufficient manpower in the rural areas and strain on services within the cities, were perceived as a growing problem by the governments. There is a direct correlation between the governments' perception of the con- sequences of this youth cohort development and the enactment of programs for youth in national development. -

2017 Almanac Final Final.Cdr

THE METHODIST CHURCH GHANA CONFERENCE OFFICE, WESLEY HOUSE E252/2, LIBERIA ROAD P. O. BOX GP 403, ACCRA, TEL: 0302 670355 / 679223 WEBSITE: www.methodistchurch_gh.org Email: [email protected] PRESIDING BISHOP: THE MOST REV. TITUS K. AWOTWI PRATT, BA, MA LAY PRESIDENT: MR. KWAME AGYAPONG BOAFO, BA (HONS.), Q.C.L., BL. ADMINISTRATIVE BISHOP: THE RT REV. DR. PAUL KWABENA BOAFO, BA., PhD. DIOCESES BISHOPS LAY CHAIRMEN SYNOD SECRETARIES CAPE COAST The Rt. Rev. Ebenezer K. Abaka-Wilson, BA, MEd Bro. Titus D. Essel Very Rev. Richardson Aboagye Andam, BA MPhil ACCRA The Rt. Rev. Samuel K. Osabutey, BA., MA., PEM (ADR) Bro. Joseph K. Addo, CA, MBA Very Rev. Sampson N. A. M. Laryea Adjei, BTh KUMASI The Rt. Rev. Christopher N. Andam, BA., MSc., MBA Bro. Prof. Seth Opuni Asiama, BSc., PhD Very Rev. Stephen K. Owusu, BD, ThM, MPhil SEKONDI The Rt. Rev. Daniel De-Graft Brace, BA., MA Bro. George Tweneboah-Kodua, BEd, MSc Very Rev. Comfort Quartey-Papafio, MTS., ThM WINNEBA The Rt. Rev. Dr. J. K. Buabeng-Odoom, BEd., MEd., DMin Bro. Nicholas Taylor, BEd, MEd Very Rev. Joseph M. Ossei, BA., MPhil KOFORIDUA The Rt. Rev. Michael Agyakwa Bossman, BA., MPhil Bro. Samuel B. Mensah Jnr., BEd Very Rev. Samual Dua Dodd, BTh., D.Min SUNYANI The Rt. Rev. Kofi Asare Bediako, BA., MSc Sis. Grace Amoako Very Rev. Daniel K. Tannor, BA, MPhil TARKWA The Rt. Rev. Thomas Amponsah-Donkor, BA., LLB, BL Bro. Joseph K. Amponsah, BEd Very Rev. Nicholas Odum Baido, BA., MA NORTHERN GHANA The Rt. Rev. Dr. -

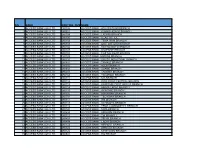

Osu Watson Branch 2 Access Bank

S/N BANK ROUTING_NUMBERNAME 1 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280105 ACCESS BANK - OSU WATSON BRANCH 2 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280601 ACCESS BANK - KUMASI ASAFO BRANCH 3 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280104 ACCESS BANK - LASHIBI BRANCH 4 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280100 ACCESS BANK - HEAD OFFICE 5 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280102 ACCESS BANK - TEMA MAIN BRANCH 6 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280103 ACCESS BANK - OSU OXFORD BRANCH 7 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280106 ACCESS BANK - KANTAMANTO BRANCH 8 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280107 ACCESS BANK - KANESHIE BRANCH 9 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280108 ACCESS BANK - CASTLE ROAD BRANCH 10 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280109 ACCESS BANK -MADINA BRANCH 11 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280110 ACCESS BANK - SOUTH INDUSTRIAL BRANCH 12 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280801 ACCESS BANK - TAMALE BRANCH 13 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280602 ACCESS BANK - ADUM BRANCH 14 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280603 ACCESS BANK - SUAME BRANCH 15 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280401 ACCESS BANK - TARKWA BRANCH 16 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280402 ACCESS BANK - TAKORADI BRANCH 17 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280111 ACCESS BANK - NIA BRANCH 18 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280112 ACCESS BANK - RING ROAD CENTRAL BRANCH 19 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280113 ACCESS BANK - KANESHIE POST OFFICE BRANCH 20 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280114 ACCESS BANK - ABEKA LAPAZ BRANCH 21 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280115 ACCESS BANK - OKAISHIE BRANCH 22 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280116 ACCESS BANK - ASHAIMAN BRANCH 23 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280701 ACCESS BANK - TECHIMAN BRANCH 24 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280117 ACCESS BANK - IPS BRANCH 25 ACCESS BANK (GH) LTD 280118 ACCESS BANK - ACHIMOTA BRANCH -

CAP. 86 Towns Act, 1892

Towns Act, 1892 CAP. 86 CAP. 86 TOWNS ACT, 1892 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Regulation of Streets, Buildings, Wells SECTION 1. Application. 2. Supervision of streets. 3. Purchase of land for streets. 4. Taking materials for streets and bridges. 5. Regulation of line of building. 6. Unlawful excavations in street. 7. Construction of bridges over open streets drains. 8. Removal of projections and obstructions. 9. Building Regulations. 10. Unauthorised buildings. 11. Penalties. 12. New buildings. 13. Recovery of expenses. Dangerous Buildings 14. Fencing of ruinous or dangerous buildings. Enclosure of Town Lands 15. Fencing of land. 16. Trimming offences. Health Areas 17. Regulation of erection of buildings. Open Spaces 18. Open spaces. 19. Removal of buildings unlawfully erected. Naming Street and Numbering Houses 20. Naming of streets. 2 I. Numbering of houses. 22. Penalty for damaging name boards. Abatement of Fires 23. Demolition to prevent spread of fire. Slaughter-houses and Markets 24. Provision of slaughter-houses and markets. 25. Weighing and measurement of market produce. VII-2951 [Issue I] CAP. 86 Towns Act, 1892 SECTION 26. Prohibition of sales outside markets. 27. Regulations for slaughter-houses and markets. 28. Regulation of sales of meat. Nuisances 29. Definition of nuisances. 30. Inspection of nuisances. 31. Information of nuisances. 32. Notice to abate nuisance. 33. Power to abate nuisance. 34. Powers of entry to abate nuisance. 35. Overcrowding. 36. Prohibition of use of unfit buildings. 37. Prevention of fouling of drinking water. 38. Regulations on nuisances. Infectious Diseases 39. Cleansing and disinfecting premises. 40. Prohibition on letting infected houses. 41. Prohibition on exposure of infected persons or things. -

Ghana – Floods Situation Report #2 29Th June 2010

Ghana – Floods Situation Report #2 29th June 2010 This report was issued by OCHA Humanitarian Support Unit in Ghana. It covers the period from 22nd to 29th June 2010. The next report will be issued on or around 2nd July 2010. I. HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES The number of the affected population rises to 25,000 with the Central region identified as the worst hit - 17,400 people affected. Rapid assessments ongoing in affected areas to determine the impact of floods on population and infrastructure II. Situation Overview Many parts of southern Ghana continued to register heavy rainfall throughout the week. As of June 29th, the latest figures from NADMO indicated that at least 25,000 people were seriously affected by the floods in three regions. As a result, the Government of Ghana has set up a High Level Task Force consisting of senior members of the Government to advice and make recommendations to the President on how best to respond to the ongoing flood situation. On June 24th, a joint assessment conducted in Greater Accra – Tema and Ashaiman areas confirmed that at least several people were still inundated and were housed in school or church institutions i.e. all the 227 people affected in Tema. In Central region, 200 people are staying in Swedru Town Hall while 150 others are camped at LA school in Agona Nyakrom. Elsewhere, communities living around Weija dam in Accra were reported to be in threat as water levels continued to raise prompting opening of flood gates. In Volta region, communities living in Adafianu, Adina and Amutinu settlements of Ketu South District remain submerged. -

Microfilms International 300 N ZEEB ROAD

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Office of Government Machinery

REPUBLIC OF GHANA MEDIUM TERM EXPENDITURE FRAMEWORK (MTEF) FOR 2021-2024 OFFICE OF GOVERNMENT MACHINERY PROGRAMME BASED BUDGET ESTIMATES For 2021 Transforming Ghana Beyond Aid REPUBLIC OF GHANA Finance Drive, Ministries-Accra Digital Address: GA - 144-2024 MB40, Accra - Ghana +233 302-747-197 [email protected] mofep.gov.gh Stay Safe: Protect yourself and others © 2021. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be stored in a retrieval system or Observe the COVID-19 Health and Safety Protocols transmitted in any or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the Ministry of Finance Get Vaccinated OFFICE OF GOVERNMENT MACHINERY The OGM MTEF PBB for 2021 is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh ii | 2021 BUDGET ESTIMATES Contents PART A: STRATEGIC OVERVIEW OF THE OFFICE OF GOVERNMENT MACHINERY (OGM) ................................................................................................... 2 1. POLICY OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................... 2 2. GOAL ................................................................................................................ 2 3. CORE FUNCTIONS .......................................................................................... 2 4. POLICY OUTCOME INDICATORS AND TARGETS ....................................... 3 POLICY OUTCOME INDICATORS AND TARGETS (MINISTRY OF SPECIAL INITIATIVE AND DEVELOPMENT) ..................................................................... -

Manufacturing Capabilities in Ghana's Districts

Manufacturing capabilities in Ghana’s districts A guidebook for “One District One Factory” James Dzansi David Lagakos Isaac Otoo Henry Telli Cynthia Zindam May 2018 When citing this publication please use the title and the following reference number: F-33420-GHA-1 About the Authors James Dzansi is a Country Economist at the International Growth Centre (IGC), Ghana. He works with researchers and policymakers to promote evidence-based policy. Before joining the IGC, James worked for the UK’s Department of Energy and Climate Change, where he led several analyses to inform UK energy policy. Previously, he served as a lecturer at the Jonkoping International Business School. His research interests are in development economics, corporate governance, energy economics, and energy policy. James holds a PhD, MSc, and BA in economics and LLM in petroleum taxation and finance. David Lagakos is an associate professor of economics at the University of California San Diego (UCSD). He received his PhD in economics from UCLA. He is also the lead academic for IGC-Ghana. He has previously held positions at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis as well as Arizona State University, and is currently a research associate with the Economic Fluctuations and Growth Group at the National Bureau of Economic Research. His research focuses on macroeconomic and growth theory. Much of his recent work examines productivity, particularly as it relates to agriculture and developing economies, as well as human capital. Isaac Otoo is a research assistant who works with the team in Ghana. He has an MPhil (Economics) from the University of Ghana and his thesis/dissertation tittle was “Fiscal Decentralization and Efficiency of the Local Government in Ghana.” He has an interest in issues concerning local government and efficiency. -

Yes Double Track

Region District School Code School Name Gender Status Option ASHANTI Ejisu Juaben Municipal 0051606 Achinakrom Senior High Mixed Day/Boarding C ASHANTI Kwabre East 0050703 Adanwomase Senior High Mixed Day/Boarding C ASHANTI Sekyere South 0050605 Adu Gyamfi Senior High Mixed Day/Boarding C ASHANTI Afigya-Kwabere 0050704 Aduman Senior High Mixed Day/Boarding B ASHANTI Kumasi Metro 0050115 Adventist Senior High, Kumasi Mixed Day/Boarding B ASHANTI Kwabre East 0050707 Adventist Girls Senior High, Ntonso Girls Day/Boarding C ASHANTI Atwima Kwanwoma 0051701 Afua Kobi Ampem Girls' Senior High Girls Day/Boarding B ASHANTI Asante Akim North 0051001 Agogo State College Mixed Day/Boarding C ASHANTI Sekyere South 0050606 Agona Senior High/Tech Mixed Day/Boarding B ASHANTI Offinso North 0050802 Akumadan Senior High Mixed Day/Boarding C ASHANTI Kumasi Metro. 0050156 Al-Azariya Islamic Snr. High, Kumasi Mixed Day B ASHANTI Mampong Municipal 0050503 Amaniampong Senior High Mixed Day/Boarding C ASHANTI Kumasi Metro 0050107 Anglican Senior High, Kumasi Mixed Day/Boarding B ASHANTI Kwabre East 0050701 Antoa Senior High Mixed Day/Boarding C ASHANTI Kumasi Metro 0050113 Armed Forces Senior High/Tech, Kumasi Mixed Day/Boarding B ASHANTI Kumasi Metro 0050101 Asanteman Senior High Mixed Day/Boarding B ASHANTI Adansi North 0051206 Asare Bediako Senior High . Mixed Day/Boarding B ASHANTI Atwima Nwabiagya 0050207 Barekese Senior High Mixed Day/Boarding C ASHANTI Adansi North 0051302 Bodwesango Senior High Mixed Day/Boarding C ASHANTI Obuasi Municipal 0051204 Christ -

BANK of GHANA Banks' Swift and Sort Codes

BANK OF GHANA ___ ________ _____________ _________________ ______________________ ______________________________ _____________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Banks’ Swift and Sort Codes _____________________________________________ ________________________________________ ________________________________ __________________________ ______________________ _______________ _________ ______ ___ JUNE 2012 C o n t e n t Page 1. Introduction … … … … 2 2. Components of the Sort Code … … … … 2 3. Clearing Cycle … … … … 2 4. Bank and Swift Codes … … … … 3 5. Bank Branch Sort Code … … … … 4 6. Bank of Ghana … … … … 4 7. Standard Chartered Bank (Gh) Ltd … … … … 4 8. Barclays Bank (Gh) Ltd. … … … … 5 9. Ghana Commercial Bank Ltd. … … … … 7 10. National Investment Bank Ltd. … … … … 12 11. United Bank for Africa (Gh). Ltd. … … … … 13 12. ARB Apex Bank Ltd. … … … … 13 13. Accra Area … … … … 13 14. Koforidua Area … … … … 14 15. Cape Coast Area … … … … 15 16. Takoradi Area … … … … 15 17. Ho Area … … … … 15 18. Kumasi Area … … … … 16 19. Sunyani Area … … … … 17 20. Tamale Area … … … … 17 21. Bolgatanga Area … … … … 18 22. Wa Area … … … … 18 23. Hohoe Area … … … … 18 24. Agricultural Development Bank … … … … 18 25. SG-SSB Bank Ltd. … … … … 20 26. Merchant Bank (Gh) Ltd. … … … … 22 27. HFC Bank Ltd. … … … … 22 28. Zenith Bank (Gh) Ltd. … … … … 23 29. Ecobank (Gh) Ltd. … … … … 24 30. Cal Bank Ltd. … … … … 25 31. The Trust Bank Ltd. … … … … 26 32. UT Bank Ghana Ltd. … … … … 27 33. First Atlantic Merchant Bank Ltd. … … … … 27 34. Prudential Bank Ltd. … … … … 28 35. Stanbic Bank Ghana Ltd. … … … … 28 36. International Commercial Bank Ltd. … … … … 29 37. Amalgamated Bank Ltd. … … … … 30 38. Unibank (Gh) Ltd. … … … … 30 39. Guaranty Trust Bank Ltd. … … … … 31 40. Fedelity Bank Ghana Ltd. … … … … 31 41. Intercontinental Bank (Gh) Ltd. … … … … 32 42. Bank of Baroda (Gh) Ltd. … … … … 33 43.