Sport for Development and Peace in Post-Yugoslav Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 (Pdf) Download

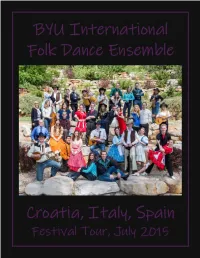

Table of Contents IFDE Personnel List……………………...………………………………………3 Tour Itinerary……………………………………………………..……………….5 Dances for Summer Tour……………………………………………………….16 Tour Journal…………………………………………………………………...…17 Audience Remarks……………………………………………………………...34 Photo Gallery……………………………………………………………...…….35 2 International Folk Dance Ensemble Personnel List 2015 Extended Single Women 1. Mauresa Bastian (band) 2. Gracy Dayton (band) 3. Whitney DeMille 4. Kylie Falke 5. Katie Farrenkopf 6. Katie Haddock 7. Emilee Hardy (band) 8. Sydnie Keddington (band) 9. Rebecca Kiser 10. Victoria Leavitt 11. Sirie McCoy (traveling as Jensen) 12. Jessa Miles 13. Allison Oberle (traveling as Jardine) 14. Carrie Ostler (band) 15. Ariel Peterson 16. Lauren Piperato 17. Julianna Sheffield 18. Amber Shepherd 19. Amanda Welch Single Men 1. Jason Allen 2. Abram Allred 3. Jacob Bagley (band) 4. Jason Checketts 5. Thomas Clements 6. Zach Diamond 7. Will Farnbach 8. Talmage Haines (band) 9. Taylor Haycock 3 10. Michael Kim 11. Cameron King 12. Tanner Long 13. Garett Madril 14. Sean Nicholes 15. Nathan Pehrson 16. Wesley Valdez Tour Leaders 1. Colleen West, Artistic Director 2. Troy Streeter, Tour Manager (July 2-16) 3. Shane Wright, Tour Manager (July 16-30) 4. Jeff West, Chaperone 5. Mark Ohran, Technical Director 6. Mark Philbrick, Photographer (July 16-30) 7. Peggy Philbrick, Chaperone Trainer 1. Brenda Critchfield 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 DANCES FOR SUMMER TOUR 2015 Traditional American Dances: 1. Texas Fandango 2:31 (12 men) 2. Calico Darlin’ 2:00 (12 women) 3. Exhibition Square 3:12 (12 couples) 4. Jumbleberry Hoedown 2:43 (10 couples) 5. Appalachian Patchwork 5:52 (12 couples) 6. Boot Kickin’ - Western Swing 3:32 (8 couples) 7. -

Zagreb, You Get the Best out of Your Visit Winners of 20 of the 28 League to Football’S Furthest Corners and Campaigns Since the War-Torn Ones Showcase Stadiums

www.liberoguide.com CROATIA 2019-20 www.liberoguide.com Croatia emerged from conflict and post-Communist industrial decline to become Europe’s most sought-after Med getaway. INTRO This transformational marketing triumph has dovetailed with the national team taking the world stage in the red-and-white chequerboard of the Croatian coat of arms, the šahovnica. This has created a brand of universal Welcome to recognition, the replica tops standard liberoguide.com! holiday issue along Croatia’s extensive The digital travel guide for coastline. When Croatian president football fans, liberoguide.com Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović braved the is the most up-to-date resource, torrential rain after her compatriots city-by-city, club-by-club, to the had gallantly pushed France to the wire game across Europe and North in the 2018 World Cup Final, she was America. Using only original soaked to the skin in the chequerboard photos and first-hand research, shirt, surrounded by men in suits. As taken and undertaken over seven a symbol of Croatian spirit before a seasons, liberoguide.com has global audience of 1.1 billion, it was been put together to enhance brilliant. every football weekend and Euro night experience. From airport By stark comparison, the domestic to arena, downtown sports bar game in Croatia is meek and seen by to hotel, liberoguide.com helps few. Dominated by Dinamo Zagreb, you get the best out of your visit winners of 20 of the 28 league to football’s furthest corners and campaigns since the war-torn ones showcase stadiums. Kantrida, Rijeka of the early 1990s, the Croatian top- flightPrva HNL has juggled with sizes and formulas but gates rarely break a on thin margins despite winning every CROATIA 2019-20 seasonal average of 3,000. -

15 Days 13 Nights Medjugorje, Eastern Europe Pilgrimage

25-09-2018 15 DAYS 13 NIGHTS MEDJUGORJE, EASTERN EUROPE PILGRIMAGE (Vienna, Dubrovnik, Medjugorje, Mostar, Sarajevo, Zagreb, Budapest, Krakow, Wadowice, Czestochowa & Prague Departure dates: 25th May / 15th Jun / 19th Oct 2019 Spiritual Director: TBA (Final Itinerary subject to airlines confirmation) Itinerary: DAY 1: BORNEO OR KUL – DUBAI - ZAGREB (MEAL ON BOARD) • Borneo Pilgrims – Depart KKIA to KLIA and meet main group at Emirate Check in counter. • KL Pilgrims - Assemble 3 hours before at Emirate check in counter • Flight departs after midnight at 1.55am for Zagreb via Dubai (Transit 3hrs 30mins). DAY 2: ZAGREB (L,D) Arrive Zagreb at 12.35 noon. After immigration and baggage clearance, meet and proceed for half day City tour. ❖ Funicular journey to upper town Gornji Grad, view of Zagreb Cathedral, Bloody Bridge. visit the St Mark’s Square which consists of the Parliament Building, Lotrscak Tower, Tkalciceva Street ➢ Cathedral of Assumption - it is the symbol of Zagreb with its two neo-Gothic towers dominating the skyline at 104 and 105 metres. In the Treasury of the Cathedral, above the sacristy, priceless treasures have been stored, including the artefacts from 11th to 19th century. Many great Croats had been buried inside the Cathedral. ➢ St Mark’s Square - St. Mark’s Church that was built in the mid-13th century dominates this most beautiful square of the Upper Town. Many events crucial for Zagreb and entire Croatia took place here and many important edifices and institutions are located in this relatively tight space. The most attractive of all is St. Mark’s Church with its Romanesque naves, Gothic vaults and sanctuary and picturesque tiles on its multi-coloured roof that are arranged in such way that they form historical coats of arms of Zagreb and Croatia. -

Slovenia, Croatia Guided Tour Countries of Freedom and Ecology 8 Days / 7 Nights

Slovenia, Croatia Guided Tour Countries of Freedom and Ecology 8 Days / 7 Nights Croatia – is ideally situated at the crossroads of Central Europe and the Mediterranean. The Croatian coast line and the mainland area, islands and islets make Croatia an attractive country to visit. The country’s natural treasures which include crystal-clear seas, remote islands, unspools fishing villages, beaches, vineyards, Roman ruins and medieval walled cities. An abundance of natural harbors lures yachters, and naturists have their own beaches. There’s an island for every taste. Along the Adriatic coast you will find remains of palaces, temples and amphitheaters from the Roman Empire as well as Forts, fortified towns built during the Venetian Rule. Each of the Rulers had left its strong imprint on the architecture of the interior, particularly in the baroque cities that flourished in the 17th and the 18th centuries. Religion in the form of Roman Catholic Church has been essential to the Croatian identity since the 9th century. That’s the reason we can find Mail: [email protected] many churches and Cathedrals since the very early 9th century all over Croatia in different kind of architecture, monasteries and convents most of them preserved till actual time side by side to the Castles, the fortified walls towns, Museums and Galleries all over the country. Croatia is an ecologic country, preserving the Fauna and Flora, the important Natural Reserves and Natural Parks declared by UNESCO as World Heritage such as Plitvice Natural Park, one of the seven natural treasures of the country as well as towns and cities. -

The Politics of Lustration in Eastern Europe a Dissertation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy Dealing with Communist Legacies: The Politics of Lustration in Eastern Europe A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Ryan Moltz IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Ron Aminzade, Adviser January 2014 © Ryan Moltz 2014 Acknowledgements This dissertation is in part about the path dependency of politics. In that spirit, I have to begin by thanking Professor James R. Bruce, my undergraduate advisor at Hendrix College. Had I not taken his introduction to sociology course in the spring of 2001, I most certainly would not now be writing a doctoral dissertation in that subject. The key to surviving graduate school is a good support system. I was lucky to have that right from the beginning of my time in Minneapolis. I had the best graduate cohort that I could have hoped for: Ryan Alaniz, Amelia Corl, Shannon Golden, Rachelle Hill, Jeanette Husseman, Heather McLaughlin, Jeremy Minyard, Kirsten O’Brien, and Dan Winchester. My friends Jack Lam, jim saliba, and Tim Ortyl made life off campus especially fun. Tim, you are greatly missed. My dissertation would not have taken this form without the influence of my adviser, Ron Aminzade. Ron always pushed my thinking in new directions, urged me to consider evidence in alternative ways, and provided invaluable feedback at every stage of the research process. The work of several other professors has also profoundly shaped this dissertation. In particular, I acknowledge the influence of Liz Boyle, Joachim Savelsberg, Fionnuala Ni Aolain, Kathryn Sikkink, and Robin Stryker. -

Second International Congress of Art History Students Proceedings !"#$%&&'"

SECOND INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF ART HISTORY STUDENTS PROCEEDINGS !"#$%&&'" !"#$%&'() Klub studenata povijesti umjetnosti Filozofskog fakulteta (Art History Students' Association of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences) (*%+,)%-$ #,-)* Jelena Behaim, Kristina Brodarić, Lucija Bužančić, Ivan Ferenčak, Jelena Mićić, Irena Ravlić, Eva Žile )(.%(/()& Tanja Trška, Maja Zeman (*%+%01 -0* !),,2)(-*%01 Ivana Bodul, Kristina Đurić, Petra Fabijanić, Ana Kokolić, Tatjana Rakuljić, Jasna Subašić, Petra Šlosel, Martin Vajda, Ira Volarević *(&%10 + $-3,"+ Teo Drempetić Čonkić (oprema čonkić#) The Proceedings were published with the financial support from the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Zagreb. SECOND INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF ART HISTORY STUDENTS PROCEEDINGS !"#$%&'() Klub studenata povijesti umjetnosti Filozofskog fakulteta (Art History Students' Association of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences) %&#* 978-953-56930-2-4 Zagreb, 2014 ƌ TABLE OF CONTENTS ! PREFACE " IS THERE STILL HOPE FOR THE SOUL OF RAYMOND DIOCRÈS? THE LEGEND OF THE THREE LIVING AND THREE DEAD IN THE TRÈS RICHES HEURES — )*+,- .,/.0-12 #" THE FORGOTTEN MACCHINA D’ALTARE IN THE CHURCH LADY OF THE ANGELS IN VELI LOŠINJ — 3*/+, 45*6),7 $% GETTING UNDER THE SURFACE " NEW INSIGHTS ON BRUEGEL’S THE ASS AT SCHOOL — 8*69/* +*906 &' THE FORMER HIGH ALTAR FROM THE MARIBOR CATHEDRAL — -*706:16* 5*-71; (% EVOCATION OF ANTIQUITY IN LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY ART: THE TOILETTE OF AN ATHENIAN WOMAN BY VLAHO BUKOVAC — *6* 8*3*/9<12 %& A TURKISH PAINTER IN VERSAILLES: JEAN#ÉTIENNE LIOTARD AND HIS PRESUMED PORTRAIT OF MARIE!ADÉLAÏDE OF FRANCE DRESSED IN TURKISH COSTUME — =,)*6* *6.07+,-12 ># IRONY AND IMITATION IN GERMAN ROMANTICISM: MONK BY THE SEA, C.$D. -

Memorial of the Republic of Croatia

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING THE APPLICATION OF THE CONVENTION ON THE PREVENTION AND PUNISHMENT OF THE CRIME OF GENOCIDE (CROATIA v. YUGOSLAVIA) MEMORIAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA APPENDICES VOLUME 5 1 MARCH 2001 II III Contents Page Appendix 1 Chronology of Events, 1980-2000 1 Appendix 2 Video Tape Transcript 37 Appendix 3 Hate Speech: The Stimulation of Serbian Discontent and Eventual Incitement to Commit Genocide 45 Appendix 4 Testimonies of the Actors (Books and Memoirs) 73 4.1 Veljko Kadijević: “As I see the disintegration – An Army without a State” 4.2 Stipe Mesić: “How Yugoslavia was Brought Down” 4.3 Borisav Jović: “Last Days of the SFRY (Excerpts from a Diary)” Appendix 5a Serb Paramilitary Groups Active in Croatia (1991-95) 119 5b The “21st Volunteer Commando Task Force” of the “RSK Army” 129 Appendix 6 Prison Camps 141 Appendix 7 Damage to Cultural Monuments on Croatian Territory 163 Appendix 8 Personal Continuity, 1991-2001 363 IV APPENDIX 1 CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS1 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE CHRONOLOGY BH Bosnia and Herzegovina CSCE Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe CK SKJ Centralni komitet Saveza komunista Jugoslavije (Central Committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia) EC European Community EU European Union FRY Federal Republic of Yugoslavia HDZ Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (Croatian Democratic Union) HV Hrvatska vojska (Croatian Army) IMF International Monetary Fund JNA Jugoslavenska narodna armija (Yugoslav People’s Army) NAM Non-Aligned Movement NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organisation -

Upute Za Slučaj Potresa U Gradu Zagrebu Grad Zagreb

Grad Zagreb Upute za slučaj potresa u Gradu Zagrebu Ured za upravljanje u hitnim situacijama Evakuacijski koridori, Općenito o potresima prihvatne površine Do potresa dolazi uslijed pomicanja tektonskih ploča u unutrašnjosti Zemlje, a posljedica je podrhtavanje Zemljine kore zbog oslobađanja velike količine energije. Potres opisujemo dvjema različitim mjerama: magnitudom i intenzitetom potresa. Magnituda potresa je egzaktna mjera energije koja je u slučaju evakuacije oslobođena prilikom potresa, mjeri se seizmografima, a izražava se stupnjevima Richtera. Intenzitet potresa opisuje posljedice koje je potres proizveo na Zemljinoj površini, a iskazuje se s pomoću „tradicionalne“ Mercalli-Cancani-Siebergove (MCS) ljestvice ili novije Europske makroseizmičke ljestvice građana i površine za (EMS). Obje ljestvice sadržavaju 12 stupnjeva, a opisuju razornost i posljedice potresa na Zemljinoj površini. Najučinkovitija preventivna mjera zaštite jest protupotresna gradnja građevina projektirana sukladno Pravilniku o tehničkim normativima za izgradnju objekata visokogradnje u odnosu na potresnu postavljanje šatorskih zonu u kojoj se objekt nalazi. naselja u slučaju potresa Opće činjenice o potresu: • potres ne ubija, ubijaju građevine i dijelovi građevina; • poznato je da se potres može dogoditi te da se može predvidjeti njegova jačina, ali ne i vrijeme njegova zbivanja; • najbolja preventiva je dobro planiranje, projektiranje i gradnja prema načelima protupotresnoga graditeljstva; M 1:40000 • potrebno je stalno educiranje stanovništva i osposobljavanje operativnih snaga. Skraćeni oblik Europske makroseizmičke ljestvice Magnituda po Intenzitet 1. Jagodnjak - LZPO - GČ Brezovica Definicija Opis tipičnih učinaka (skraćeno)2 Richteru M 1 po EMS-98 2. Igralište Odranski obrež - Krčevine - LZPO - R GČ Brezovica 1,0 - 3,0 I. Ne osjeti se Ne osjeti se. Dvorac Brezovica - EVAP - GČ Brezovica II. -

The Genealogy of Dislocated Memory: Yugoslav Cinema After the Break

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses April 2014 The Genealogy of Dislocated Memory: Yugoslav Cinema after the Break Dijana Jelaca University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jelaca, Dijana, "The Genealogy of Dislocated Memory: Yugoslav Cinema after the Break" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 10. https://doi.org/10.7275/vztj-0y40 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/10 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GENEALOGY OF DISLOCATED MEMORY: YUGOSLAV CINEMA AFTER THE BREAK A Dissertation Presented by DIJANA JELACA Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2014 Department of Communication © Copyright by Dijana Jelaca 2014 All Rights Reserved THE GENEALOGY OF DISLOCATED MEMORY: YUGOSLAV CINEMA AFTER THE BREAK A Dissertation Presented by DIJANA JELACA Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________ Leda Cooks, Chair _______________________________________ Anne Ciecko, Member _______________________________________ Lisa Henderson, Member _______________________________________ James Hicks, Member ____________________________________ Erica Scharrer, Department Head Department of Communication TO LOST CHILDHOODS, ACROSS BORDERS, AND TO MY FAMILY, ACROSS OCEANS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is about a part of the world that I call “home” even though that place no longer physically exists. I belong to that “lost generation” of youth whose childhoods ended abruptly when Yugoslavia went up in flames. -

The Croats Under the Rulers of the Croatian National Dynasty

THE CROATS Fourteen Centuries of Perseverance Publisher Croatian World Congress (CWC) Editor: Šimun Šito Ćorić Text and Selection of Illustrations Anđelko Mijatović Ivan Bekavac Cover Illustration The History of the Croats, sculpture by Ivan Meštrović Copyright Croatian World Congress (CWC), 2018 Print ITG d.o.o. Zagreb Zagreb, 2018 This book has been published with the support of the Croatian Ministry of culture Cataloguing-in-Publication data available in the Online Catalogue of the National and University Library in Zagreb under CIP record 001012762 ISBN 978-953-48326-2-2 (print) 1 The Croats under the Rulers of the Croatian National Dynasty The Croats are one of the oldest European peoples. They arrived in an organized manner to the eastern Adriatic coast and the re- gion bordered by the Drina, Drava and Danube rivers in the first half of the seventh century, during the time of major Avar-Byzan- tine Wars and general upheavals in Europe. In the territory where they settled, they organized During the reign of Prince themselves into three political entities, based on the previ Branimir, Pope John VIII, ous Roman administrative organizations: White (western) the universal authority at Croatia, commonly referred to as Dalmatian Croatia, and Red the time, granted (southern) Croatia, both of which were under Byzantine su Croatia international premacy, and Pannonian Croatia, which was under Avar su recognition. premacy. The Croats in Pannonian Croatia became Frankish vassals at the end of the eighth century, while those in Dalmatia came under Frankish rule at the beginning of the ninth century, and those in Red Croatia remained under Byzantine supremacy. -

THE SERBS AGAINST the WEHRMACHT a History of World War Two in Yugoslavia Based on Previously Unknown German Documents

Miloslav Samardzic THE SERBS AGAINST THE WEHRMACHT A History of World War Two in Yugoslavia Based on previously unknown German documents Translated by: Nebojsa Malic Kragujevac, 2018. CONTENTS Foreword: In Search of German Documents . .7 1. The 1941 uprising . .13 2. The Battle of Cer . .24 3. Operations “Ozren”, “Ozren 2“, “Bader-Ostbosnien” and “Trio” . .36 4. Other battles in 1942 . 44 5. Sabotage and diversions during the “Battle for Supplies” . .48 6. The “Gordon” group . .58 7. Operations until September 1943 . .61 8. A daily report from the German commander of Serbia . .71 9. Lim, Drina and the coast: Operations following the Italian Surrender . 73 10. Other operations through December 1943 . .79 11. Railway attacks in the fall of 1943 . .86 12. Battle of Višegrad . .93 13. Lim Bridge is Down . .107 14. Semeć Field . .112 15. Report by the 369th Division HQ on October 10, 1943 . 132 16. Breaking through the Jabuka-Mesići-Rogatica Line . 137 17. The Siege of Sarajevo . .154 18. Siege of Sarajevo Ends . .174 19. German Response to the Chetnik Offensive . .186 20. First half of 1944 . .190 21. Fourth Chetnik Offensive Against the Axis . .199 22. Chetnik-inflicted German Losses . .224 23. Analysis of German Losses: Chetniks vs. Partisans . .234 Documents and Photos . 113 Endnotes . .238 Sources . .250 About the Author . .253 Foreword: In Search of German Documents Anyone wishing to give an accurate description of combat operations by the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland (a.k.a. “Chet - niks“) faces two principal challenges. First, the need to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that such operations took place. -

LARSON-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf

THE NEW “OLD COUNTRY” THE KINGDOM OF YUGOSLAVIA AND THE CREATION OF A YUGOSLAV DIASPORA 1914-1951 BY ETHAN LARSON DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Maria Todorova, Chair Professor Peter Fritzsche Professor Diane Koenker Professor Ulf Brunnbauer, University of Regensburg ABSTRACT This dissertation reviews the Kingdom of Yugoslavia’s attempt to instill “Yugoslav” national consciousness in its overseas population of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, as well as resistance to that same project, collectively referred to as a “Yugoslav diaspora.” Diaspora is treated as constructed phenomenon based on a transnational network between individuals and organizations, both emigrant and otherwise. In examining Yugoslav overseas nation-building, this dissertation is interested in the mechanics of diasporic networks—what catalyzes their formation, what are the roles of international organizations, and how are they influenced by the political context in the host country. The life of Louis Adamic, who was a central figure within this emerging network, provides a framework for this monograph, which begins with his arrival in the United States in 1914 and ends with his death in 1951. Each chapter spans roughly five to ten years. Chapter One (1914-1924) deals with the initial encounter between Yugoslav diplomats and emigrants. Chapter Two (1924-1929) covers the beginnings of Yugoslav overseas nation-building. Chapter Three (1929-1934) covers Yugoslavia’s shift into a royal dictatorship and the corresponding effect on its emigration policy.