Olj Vol 4, No 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.RANGELAND DEGRADATION: EXTENT

Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems E-ISSN: 1870-0462 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán México Mussa, Mohammed; Hashim, Hakim; Teha, Mukeram RANGELAND DEGRADATION: EXTENT, IMPACTS, AND ALTERNATIVE RESTORATION TECHNIQUES IN THE RANGELANDS OF ETHIOPIA Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems, vol. 19, núm. 3, septiembre-diciembre, 2016, pp. 305-318 Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán Mérida, Yucatán, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=93949148001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems, 19 (2016): 305 - 318 Musa et al., 2016 Review [Revisión] RANGELAND DEGRADATION: EXTENT, IMPACTS, AND ALTERNATIVE RESTORATION TECHNIQUES IN THE RANGELANDS OF ETHIOPIA1 [DEGRADACIÓN DE PASTIZALES: EXTENSIÓN, IMPACTOS, Y TÉCNICAS DE RESTAURACIÓN ALTERNATIVAS EN LOS PASTIZALES DE ETIOPÍA] Mohammed Mussa1* Hakim Hashim2 and Mukeram Teha3 1Maddawalabu University, Department of Animal and Range Science, Bale-Robe, Ethiopia. Email: [email protected] or [email protected] 2Maddawalabu University, Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension, Bale-Robe, Ethiopia 3Haramaya University, Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension, Dire-Dawa, Ethiopia *Corresponding author SUMMARY Rangeland degradation remains a serious impediment to improve pastoral livelihoods in the lowlands of Ethiopia. This review paper presents an overview of the extent of rangeland degradation, explores its drivers, discusses the potential impacts of rangeland degradation and also suggests alternative rangeland restoration techniques. It is intended to serve as an exploratory tool for ensuing more detailed quantitative analyses to support policy and investment programs to address rangeland degradation in Ethiopia. -

Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of the Drought Response in Ethiopia 2015 - 2018

Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of the Drought Response in Ethiopia 2015 - 2018 Independent assessment of the collective humanitarian response of the IASC member organizations November 2019 an IASC associated body Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of the Drought Response in Ethiopia Final version, November 2019 Evaluation Team The Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation (IAHE) was conducted by Dr. Julia Steets (GPPi, Team Leader), Ms. Claudia Meier (GPPi, Deputy Team Leader), Ms. Doe-e Berhanu, Dr. Solomon Tsehay, Ms. Amleset Haile Abreha. Evaluation Management Management Group members for this project included: Mr. Hicham Daoudi (UNFPA) and Ms. Maame Duah (FAO). The evaluation was managed by Ms. Djoeke van Beest and Ms. Tijana Bojanic, supported by Mr. Assefa Bahta, in OCHA’s Strategic Planning, Evaluation and Guidance Section. Acknowledgments: The evaluation team wishes to express its heartfelt thanks to everyone who took the time to participate in interviews, respond to surveys, provide access to documents and data sets, and comment on draft reports. We are particularly grateful to those who helped facilitate evaluation missions and guided the evaluation process: the enumerators who travelled long distances to survey affected people, the OCHA Ethiopia team, the Evaluation Management Group and the Evaluation Managers, the in-country Advisory Group, and the Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation Steering Group. Cover Photo: Women weather the microburst in Ber'aano Woreda in Somali region of Ethiopia. Credit: UNICEF Inter-Agency Humanitarian -

A Week in the Horn 14.3.2014 News in Brief the 25 Extraordinary Summit of IGAD Heads of State and Government President Kenyatta

A Week in the Horn 14.3.2014 News in Brief The 25th Extraordinary Summit of IGAD Heads of State and Government President Kenyatta’s official visit to Ethiopia Prime Minister Hailemariam meets EU Ambassadors Dr. Tedros makes working visits to Angola and South Africa Addis Ababa and Khartoum Universities hold a Symposium on the Nile Ethiopia has the potential to become a top international tourist destination News in Brief African Union IGAD Heads of State met on Thursday (March 13) in Addis to discuss the details of a proposed stabilization and protection force for South Sudan. Kenya, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Djibouti and Burundi, have indicated they are ready to send troops to South Sudan. (See article) The IGAD Council of Ministers met on Wednesday (March 12) in Addis Ababa in closed session to hear a report from Ambassador Seyoum Mesfin, Chairperson of the IGAD Special Envoys on the ongoing mediation process for South Sudan. (See article) The African Union on Friday (March 7) announced the team for the Commission of Enquiry to investigate human rights violations and abuses committed in South Sudan in mid-December last year. Headed by former Nigerian President, Olusegun Obasanjo, the other members of the Commission are Ugandan academic Mahmood Mamdani, Justice Sophia Akuffo, president of the African Court on Human Rights based in Arusha, Bineta Diop, AU special envoy for women, peace and security, and Professor Pacifique Manirakiza, a member of the African Commission on Human Rights. Ambassador Girma Birru, Ambassador of Ethiopia to the US told African Ambassadors in Washington this week that all necessary preparations had been made to ensure the smooth running of the US-Africa Energy Ministerial to be held in Addis Ababa (June 3-4) under the theme "Catalyzing Sustainable Growth in Africa." The Ministerial will be co-hosted by the Governments of Ethiopia and the US and will deal with topics of critical energy policy, governance and investment, renewable energy, finance and Power Africa. -

Algemeen Ambtsbericht Ethiopië

Algemeen ambtsbericht Ethiopië December 2010 Directie Consulaire Zaken en Migratie Afdeling Asiel, Hervestiging en Terugkeer Postbus 20061 2500 EB DEN HAAG Algemeen Ambtsbericht Ethiopië /december 2010 Inhoudsopgave Pagina 1 Inleiding 4 2 Landeninformatie 5 2.1 Basisgegevens 5 2.1.1 Land en volk 5 2.1.2 Geschiedenis 6 2.1.3 Staatsinrichting 14 2.2 Politieke ontwikkelingen 16 2.3 Veiligheidssituatie 23 2.4 Corruptie 32 3 Mensenrechten 33 3.1 Juridische context 33 3.1.1 Internationale verdragen en protocollen 33 3.1.2 Nationale wetgeving 34 3.2 Toezicht 34 3.3 Naleving en schendingen 37 3.3.1 Persvrijheid en vrijheid van meningsuiting 37 3.3.2 Vrijheid van vereniging en vergadering 41 3.3.3 Vrijheid van godsdienst 48 3.3.4 Bewegingsvrijheid 49 3.3.5 Rechtsgang 53 3.3.6 Arrestaties en detentie 54 3.3.7 Mishandeling en foltering 57 3.3.8 Verdwijningen 58 3.3.9 Buitengerechtelijke executies en moorden 58 3.3.10 Doodstraf 59 3.4 Positie van specifieke groepen 60 3.4.1 Vrouwen 60 3.4.2 Minderjarigen 65 3.4.3 Homoseksuele mannen en vrouwen 68 3.4.4 In Ethiopië woonachtige personen van (gedeeltelijk) Eritrese afkomst 70 3.4.5 Etnische groepen en minderheden 72 3.4.6 Dienstweigeraars en deserteurs 74 3.4.7 Mensenrechtenschenders uit de tijd van de DERG 75 4 Migratie 76 4.1 Migratiestromen 76 4.2 Binnenlands ontheemden 80 4.3 Opvang in de regio 81 4.4 Activiteiten van internationale organisaties 83 2 Algemeen Ambtsbericht Ethiopië /december 2010 5 Literatuurlijst 84 Bijlage I Afkortingenlijst Bijlage II Kaart Ethiopië Bijlage III Partijen en bewegingen 3 Algemeen Ambtsbericht Ethiopië /december 2010 1 Inleiding In dit algemene ambtsbericht wordt de situatie in Ethiopië beschreven voor zover deze van belang is voor de beoordeling van asielverzoeken van personen die afkomstig zijn uit Ethiopië en voor besluitvorming over de terugkeer van afgewezen Ethiopische asielzoekers. -

Meles Lauds Effort to Collect Pledged Money at Copenhagen

The Monthly Publication from the Ethiopian Embassy in London Ethiopian News March 2014 Issue Inside this issue GERD construction, third anniversary…to generate electricity by 2015…………………………………………3 Ethiopians mark Women’s Day………………………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Jackie Chan in Ethiopia…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Unilever, GlaxoSmithKline to invest in Ethiopia……………………………………………………………………………….9 Tourism Transformation Council launched to make Ethiopia a top tourist destination………………....11 Lonely Planet name Dallol and Lalibela as “Great Wonders”…………………………………………………………..12 Krar Collective to play at Rough Guide Live……………………………………………………………………………………13 Kenenisa wins Paris marathon debut; Great Manchester Run next………………………………………………...14 Ethiopia in the News………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………15 Coffee’s Coming Home! Ethiopia to host 4th World Coffee Conference – page 9 Ethiopia’s first female ‘Deputy PM’ Ethiopia’s Deputy PM at Global Partnership for Education (GPE) Event H.E. Aster Mammo has been appointed Minister of the Ethiopian Deputy Prime Civil Service and Good Minister, H.E. Demeke Governance Reform Cluster Mekonnen, said Ethiopia’s Coordinator with the rank impressive performance in of Deputy Prime Minister, education is the result of making her the first woman sustained economic growth, to hold such a position in a strong commitment to Ethiopia. alleviating poverty and substantial investment in The Ethiopian Parliament approved her the country's education appointment on 8th April, after she was nominated system. by Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn. He was addressing an event hosted by the All Party Prior to her appointment, she held other posts Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Global Education including Speaker of the Oromia Regional State for All entitled “Fund the Future: Tackling the Council, Youths and Sport Minister and Government crisis in financing education for all", in London on Chief Whip. -

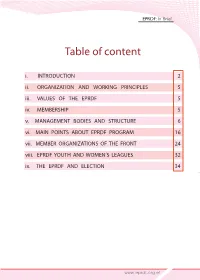

Table of Content I

EPRDF: In Brief Table of content i. INTRODUCTION 2 ii. ORGANIZATION AND WORKING PRINCIPLES 5 iii. VALUES OF THE EPRDF 5 iv. MEMBERSHIP 5 v. MANAGEMENT BODIES AND STRUCTURE 6 vi. MAIN POINTS ABOUT EPRDF PROGRAM 16 vii. MEMBER ORGANIZATIONS OF THE FRONT 24 viii. EPRDF YOUTH AND WOMEN’S LEAGUES 32 ix. THE EPRDF AND ELECTION 34 1 www.eprdf.org.et EPRDF: In Brief Secretariat of the Council of the EPRDF INTRODUCTION The Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) is a political organization founded in 1989 by the membership of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the then Ethiopian Peoples’ Democratic Movement (EPDM), currently known as the Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM). Later, other parties joined the front namely, the Oromo People’s Democratic Organization (OPDO), and the Southern Ethiopian Peoples’ Democratic Movement (SEPDM), previously known as Southern Ethiopian Peoples’ Democratic Front (SEPDF). At the outset, the objective of the front was to direct and coordinate the national liberation struggle of the people against the fascist dictatorial Dergue regime, and the fight against national oppression that was imposed over the people of Ethiopia. Accordingly, the EPRDF had waged a protracted life and death struggle which brought about the total downfall of the dictatorial military regime in May 1991. The event made an end to the age long national oppression and exploitation, 2 which was regarded as the extension of the previous regimes. Besides, the EPRDF Has also played key role in laying foundations for building a nation of a communal vision with a new spirit of hope. -

Development and Humanitarian Issues

Press Review 10 October 2017 - 17 February 2018 Deutsch-Äthiopischer Verein Press Review - Nachrichten und Meinungen aus und zu Äthiopien 10. Oktober 2017 - 17. Februar 2018 Development and Humanitarian Issues ............................................................................................. 1 Politics, Justice, Human Rights ......................................................................................................... 9 Economics ..................................................................................................................................... 103 Environment, Agriculture and Natural Resources .......................................................................... 112 Media, Culture, Religion, Education, Social and Health ................................................................ 116 Sport .............................................................................................................................................. 121 Horn of Africa and Foreign Affairs ................................................................................................. 121 Development and Humanitarian Issues 8.2.2018 UNDP and OCHA Chiefs renew call for new way of working . ReliefWeb, UNDP Report of 31.1.2018 Breaking down the silos between humanitarian and development actors to address recurrent crises The Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Achim Steiner and the United Nations Under-Secretary- General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark -

Climate Risks and Market Opportunities: Livestock Trading and Marketing in Borana, Southern Ethiopia

Climate Risks and Market Opportunities: Livestock Trading and Marketing in Borana, Southern Ethiopia Dejene Negassa Debsu Postdoctoral Research Associate, CHAINS Project and Emory Program in Development Studies, Emory University Year Two Report PROJECT ON “CLIMATE-INDUCED VULNERABILITY AND PASTORALIST LIVESTOCK MARKETING CHAINS IN SOUTHERN ETHIOPIA AND NORTHEASTERN KENYA (CHAINS)” Acknowledgements: This report was made possible by the United States Agency for International Development and the generous support of the American people through Grant No. EEM-A-00-10-0001. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the U.S. Government. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Atlanta, GA, USA October 2013 Preface This report is part of a series of field research reports from the “Climate-Induced Vulnerability and Pastoralist Livestock Marketing Chains in southern Ethiopia and northeastern Kenya (CHAINS)” project, which is part of the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Collaborative Research on Adapting Livestock Systems to Climate Change based at Colorado State University and supported by USAID Grant No. EEM-A-00-10-0001. It represents the second annual report by Dr. Dejene Negassa Debsu, a post- doctoral research associate on the project who is based in Ethiopia. The CHAINS project works with several partners in Ethiopia, including the Institute of Development Studies, Addis Ababa University and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), and -

Phd Thesis Final 04 04 12

Mycobacteria and zoonoses among pastoralists and their livestock in South-East Ethiopia INAUGURALDISSERTATION zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie Vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Basel von Balako Gumi Donde aus Ethiopia Basel, 2013 Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Basel auf Antrag von Herrn Prof. Jakob Zinsstag und Herrn Prof.Joachim Frey . Basel, October 18, 2011 Prof. Dr. Martin Spiess Dekan der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät Table of content Table of content ..................................................................................................................... 3 List of tables........................................................................................................................... 5 List of figures......................................................................................................................... 6 1. Acknowledgment ............................................................................................................... 7 2. Summary............................................................................................................................ 9 3. Summary in Amharic....................................................................................................... 12 4. Abbreviations................................................................................................................... 15 5. Introduction..................................................................................................................... -

Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of the Drought Response in Ethiopia 2015 - 2018

Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of the Drought Response in Ethiopia 2015 - 2018 Independent assessment of the collective humanitarian response of the IASC member organizations November 2019 an IASC associated body Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of the Drought Response in Ethiopia Final version, November 2019 Evaluation Team The Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation (IAHE) was conducted by Dr. Julia Steets (GPPi, Team Leader), Ms. Claudia Meier (GPPi, Deputy Team Leader), Ms. Doe-e Berhanu, Dr. Solomon Tsehay, Ms. Amleset Haile Abreha. Evaluation Management Management Group members for this project included: Mr. Hicham Daoudi (UNFPA) and Ms. Maame Duah (FAO). The evaluation was managed by Ms. Djoeke van Beest and Ms. Tijana Bojanic, supported by Mr. Assefa Bahta, in OCHA’s Strategic Planning, Evaluation and Guidance Section. Acknowledgments: The evaluation team wishes to express its heartfelt thanks to everyone who took the time to participate in interviews, respond to surveys, provide access to documents and data sets, and comment on draft reports. We are particularly grateful to those who helped facilitate evaluation missions and guided the evaluation process: the enumerators who travelled long distances to survey affected people, the OCHA Ethiopia team, the Evaluation Management Group and the Evaluation Managers, the in-country Advisory Group, and the Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation Steering Group. Cover Photo: Women weather the microburst in Ber'aano Woreda in Somali region of Ethiopia. Credit: UNICEF Inter-Agency Humanitarian -

Mcclelland Dissertation

© Copyright 2018 Jesse McClelland Planners and the Work of Renewal in Addis Ababa: Developmental State, Urbanizing Society Jesse McClelland A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: Steven Herbert, Chair Ben Gardner Lucy Jarosz Vicky Lawson Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Geography University of Washington Abstract Planners and the Work of Renewal in Addis Ababa: Developmental State, Urbanizing Society Jesse McClelland Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Steven Herbert Geography This dissertation explores the political geographies of urban restructuring through a case study of planners advancing urban renewal programs in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. I build an account of the work lives of these public servants on the basis of data from interviews, participant observation, and unobtrusive study of planning and policy documents. Amid rapid urbanization, I show that Ethiopian legacies of high modern development are gaining new expression in the EPRDF’s agenda of infrastructure-led development. Urban renewal was tentatively tried in Addis Ababa in the 1980s. But by the time of the master planning round begun in 2012, renewal had become the signature intervention of massive redevelopment of the city. Slum spaces have become the proving grounds for planners as key agents of urban governance. By drawing together insights from Marxist urban studies, socio-legal studies, and recent literature on African urbanisms, the dissertation refines scholarly understandings of the dynamic relations between governance and development in (East) African cities. Urban renewal is not reducible to a local variant on the familiar story of capitalist enclosure, and the slum is not just a space of immiseration beyond the reach of regulation. -

Recurrent Shocks, Poverty Traps and the Degradation of the Social Capital Base of Pastoralism: a Case Study from Southern Ethiopia

Center of Evaluation for Global Action Working Paper Series Agriculture for Development Paper No. AfD-0916 Issued in July 2009 Recurrent Shocks, Poverty Traps and the Degradation of the Social Capital Base of Pastoralism: A Case Study from Southern Ethiopia. Wassie Berhanu Addis Ababa University This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/cega/afd Copyright © 2009 by the author(s). Series Description: The CEGA AfD Working Paper series contains papers presented at the May 2009 Conference on “Agriculture for Development in Sub-Saharan Africa,” sponsored jointly by the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) and CEGA. Recommended Citation: Berhanu, Wassie. (2009) Recurrent Shocks, Poverty Traps and the Degradation of the Social Capital Base of Pastoralism: A Case Study from Southern Ethiopia. CEGA Working Paper Series No. AfD- 0916. Center of Evaluation for Global Action. University of California, Berkeley. Recurrent Shocks, Poverty Traps and the Degradation of the Social Capital Base of Pastoralism: A Case Study from Southern Ethiopia Wassie Berhanu* * Department of Economics, Addis Ababa University, P.O. Box 697, Code # 1110 (private) Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The long-term effects of shocks are examined in the context of a traditional pastoral community. The impacts are empirically examined in connection with the micro-level poverty trap hypothesis and the associated minimum poverty threshold estimates reported in previous studies. We argue that these estimates cannot be taken as definitive and the core explanations behind them are incongruent with the institutional realities of the pastoral community for which they are reported.