Special 40Th Issue: Focus on Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Redalyc.RANGELAND DEGRADATION: EXTENT

Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems E-ISSN: 1870-0462 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán México Mussa, Mohammed; Hashim, Hakim; Teha, Mukeram RANGELAND DEGRADATION: EXTENT, IMPACTS, AND ALTERNATIVE RESTORATION TECHNIQUES IN THE RANGELANDS OF ETHIOPIA Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems, vol. 19, núm. 3, septiembre-diciembre, 2016, pp. 305-318 Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán Mérida, Yucatán, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=93949148001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems, 19 (2016): 305 - 318 Musa et al., 2016 Review [Revisión] RANGELAND DEGRADATION: EXTENT, IMPACTS, AND ALTERNATIVE RESTORATION TECHNIQUES IN THE RANGELANDS OF ETHIOPIA1 [DEGRADACIÓN DE PASTIZALES: EXTENSIÓN, IMPACTOS, Y TÉCNICAS DE RESTAURACIÓN ALTERNATIVAS EN LOS PASTIZALES DE ETIOPÍA] Mohammed Mussa1* Hakim Hashim2 and Mukeram Teha3 1Maddawalabu University, Department of Animal and Range Science, Bale-Robe, Ethiopia. Email: [email protected] or [email protected] 2Maddawalabu University, Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension, Bale-Robe, Ethiopia 3Haramaya University, Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension, Dire-Dawa, Ethiopia *Corresponding author SUMMARY Rangeland degradation remains a serious impediment to improve pastoral livelihoods in the lowlands of Ethiopia. This review paper presents an overview of the extent of rangeland degradation, explores its drivers, discusses the potential impacts of rangeland degradation and also suggests alternative rangeland restoration techniques. It is intended to serve as an exploratory tool for ensuing more detailed quantitative analyses to support policy and investment programs to address rangeland degradation in Ethiopia. -

Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of the Drought Response in Ethiopia 2015 - 2018

Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of the Drought Response in Ethiopia 2015 - 2018 Independent assessment of the collective humanitarian response of the IASC member organizations November 2019 an IASC associated body Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation of the Drought Response in Ethiopia Final version, November 2019 Evaluation Team The Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation (IAHE) was conducted by Dr. Julia Steets (GPPi, Team Leader), Ms. Claudia Meier (GPPi, Deputy Team Leader), Ms. Doe-e Berhanu, Dr. Solomon Tsehay, Ms. Amleset Haile Abreha. Evaluation Management Management Group members for this project included: Mr. Hicham Daoudi (UNFPA) and Ms. Maame Duah (FAO). The evaluation was managed by Ms. Djoeke van Beest and Ms. Tijana Bojanic, supported by Mr. Assefa Bahta, in OCHA’s Strategic Planning, Evaluation and Guidance Section. Acknowledgments: The evaluation team wishes to express its heartfelt thanks to everyone who took the time to participate in interviews, respond to surveys, provide access to documents and data sets, and comment on draft reports. We are particularly grateful to those who helped facilitate evaluation missions and guided the evaluation process: the enumerators who travelled long distances to survey affected people, the OCHA Ethiopia team, the Evaluation Management Group and the Evaluation Managers, the in-country Advisory Group, and the Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation Steering Group. Cover Photo: Women weather the microburst in Ber'aano Woreda in Somali region of Ethiopia. Credit: UNICEF Inter-Agency Humanitarian -

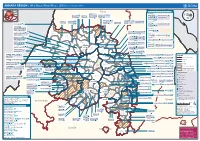

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Small Scale Hydro Power Development on Selected Existing Irrigation Dam

Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa Institute of Technology School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Small Scale Hydro Power Development on existing selected Dams in Tigray Brhane Hntsa Hailu A thesis submitted submitted to the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering stream of Hydraulic Engineering Presented in fulfilment of the requirement for degree of Masters of Science (Civil and Environmental stream of Hydraulic Engineering) Addis Ababa University Addis –Ababa, Ethiopia June, 2017 Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa Institute of Technology School of civil and environmental engineering This is to certify that the thesis prepared by Brhane Hntsa, entitled: Small Scale Hydro power Development on Selected existing Irrigation Dam in Tigray and submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Sciences (Civil Engineering stream of Hydraulic) complies with the regulation of university and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by Examining committee Advisor __________________________ Signature______________ Date__________ Internal Examiner _____________________ Signature____________ Date___________ External examiner______________________ Signature___________ Date______________ Chairman (department of graduate committee) _______ signature ________Date___________ CERTIFICATION The undersigned certify that he has read the Thesis entitled small scale hydro power development on Existing Selected Dam in Tigray and hereby recommend for acceptance by the Addis Ababa University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. _____________________________ Dr.-Ing. Asie Kemal (Supervisor) ________________________________ Date DECLARATION AND COPY RIGHT I, Brhane Hntsa Hailu, declare that this is my own original work and that it has not been presented and will not be presented to any other University for similar or any degree award. -

ETHIOPIA - TIGRAY REGION HUMANITARIAN UPDATE Situation Report Last Updated: 12 Feb 2021

ETHIOPIA - TIGRAY REGION HUMANITARIAN UPDATE Situation Report Last updated: 12 Feb 2021 HIGHLIGHTS (12 Feb 2021) As of the 12 of February, UN agencies and NGOs have received approval from the Federal Government for 53 international staff to move to Tigray. Humanitarians continue to call for the resumption of safe and unimpeded access to adequately meet the rising needs in the region, which have far outpaced the capacity to respond. Current assistance pales in comparison to the increasing needs particularly in rural areas, still out of reach and where most people lived before the conflict. Continued disruptions to essential services pose huge hurdles to the scale up of humanitarian response, more than three months into the conflict. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. © OCHA Ongoing clashes are reported in many parts of Tigray, while aid workers continue to receive alarming reports of insecurity and attacks against civilians. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (2020) CONTACTS Saviano Abreu 950,000 1.3M $1.3B $722.9M Communications Team Leader, People in need of aid Projected additional Required Received Regional Office for Southern & Eastern before the conflict people to need aid Africa A n [email protected] d , r !58% y e j r j e 61,074 $40.3M r ! r Progress Alexandra de Sousa o d Refugess in Sudan Unmet requirements S n A Deputy Head of Office, OCHA Ethiopia since 7 November for the Response Plan [email protected] FTS: https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/9 36/summary BACKGROUND (12 Feb 2021) SITUATION OVERVIEW More than three months of conflict, together with constrained humanitarian access, has resulted in a dire humanitarian situation in Tigray. -

University of Oslo Department of Informatics

UNIVERSITY OF OSLO DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATICS SUSTAINABILITY AND OPTIMAL USE OF HEALTH INFORMATION SYSTEMS: AN ACTION RESEARCH STUDY ON IMPLEMENTATION OF AN INTEGRATED DISTRICT-BASED HEALTH INFORMATION SYSTEM IN ETHIOPIA. HIRUT GEBREKIDAN DAMITEW AND NETSANET HAILE GEBREYESUS MASTER THESIS JUNE 2005 Sustainability and Optimal Use of Health Information Systems: an Action Research Study on Implementation of an Integrated District-Based Health Information System in Ethiopia By Hirut Gebrekidan Damitew and Netsanet Haile Gebreyesus A Partial Requirement for Master of Science Degree in Information System University of Oslo Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Science Department of Informatics JUNE 2005 Acknowledgements We would like to address our warm gratitude to everyone who made this research work possible. Thanks for your support. First of all we are grateful to our supervisors Judith Gregory and Jørn Braa for their professional support and guidance. We are thankful to Sundeep Sahay for his uninterrupted assistance through the fieldwork and writing up of this thesis and Jens Kaasbøll for his helpful comments on this thesis. We also thank Esselina Macome for her help with the study in Mozambique. We would also like to thank the HISP team for all input and productive discussion. We want to thank members of the Tigray team: Solomon Birhanu, Nils Fredrik Gjerull and Qalkidan Gezahegn. Warm thanks go to everyone in Tigray Regional States Health Bureau who has made this study possible and fruitful; their list is too long to mention everyone by name. Especial thanks to Dr. Tedros Adhanom, Dr. Atakilti, Dr. Teklay Kidane, Dr. Gebreab Barnabas, Ato Araya, Ato Hailemariam Kassahun, and Abraha from the regional bureau and Ato Awala, Ato Zemenfeskidus and Ato Endale from district offices. -

Olj Vol 4, No 1

Jiildii 4ffaa , L a k k . 1 Waggaatti Yeroo Tokko Kan Maxxanfamu Vol.4, No.1 Published Once Annually ISSN 2304-8239 Barruulee Articles Joornaalii Seeraa Oromiaa [Jil.4, Lakk. 1] Oromia Law Journal [Vol.4, No.1] OLD WINE IN NEW BOTTLES: BRIDGING THE PERIPHERAL GADAA RULE TO THE MAINSTREAM CONSTITUTIONAL ORDER OF THE 21 ST C. ETHIOPIA ∗ Zelalem Tesfaye Sirna ABSTRACT In sub-Saharan African countries where democracy and rule of law are proclaimed but in several circumstances not translated into practice, it appears vital to look into alternatives that can fill governance deficits. It is against this backdrop that ‘‘Old Wine in New Bottles: Bridging the Peripheral Gadaa Rule to the Mainstream Constitutional Order of the 21st Century Ethiopia” came into focus. The main objective of this article is, therefore, to respond to the search of alternative solution to hurdles democratization process, Africa as a region as well as Ethiopia as a country faces, through African indigenous knowledge of governance, namely the Gadaa System. Accordingly, institutional and fundamental principles analyzed in this article clearly indicate that indigenous system of governance such as the Gadaa System embraces indigenous democratic values that are useful in 21 st century Ethiopia. In sum, three main reasons support this article: first, in Africa no system of governance is perfectly divorced from its indigenous institutions of governance; second, indigenous knowledge of governance as a resource that could enhance democratization in Ethiopia should not be left at peripheries; and third, an inclusive policy that accommodates diversity and ensures the advancement of human culture appeals. -

World Bank Document

PA)Q"bP Q9d9T rlPhGllPC LT.CIILh THE FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA Ph,$F&,P f1~77Pq ).rlnPQnlI (*) ETHIOPIAN ROADS AUTHORITY w Port Otflce Box 1770 Addlr Ababa Ethlopla ra* ~3 ~TC1770 nRn nnrl rtms Cable Addreu Hlghways Addlr Ababa P.BL'ICP ill~~1ill,& aa~t+mn nnrl Public Disclosure Authorized Telex 21issO Tel. No. 551-71-70/79 t&hl 211860 PlOh *'PC 551-71-70179 4hb 251-11-5514865 Fax 251-11-551 866 %'PC Ref. No. MI 123 9 A 3 - By- " - Ato Negede Lewi Senior Transport Specialist World Bank Country Office Addis Ababa Ethiopia Public Disclosure Authorized Subject: APL 111 - Submission of ElA Reports Dear Ato Negede, As per the provisions of the timeframe set for the pre - appraisal and appraisal of the APL Ill Projects, namely: Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Aposto - Wendo - Negelle, 2. Gedo - Nekemte, 3. Gondar - Debark, and 4. Yalo - Dallol, we are hereby submitting, in both hard and soft copies, the final EIA Reports of the Projects, for your information and consumption, addressing / incorporating the comments received at different stages from the Bank. Public Disclosure Authorized SincP ly, zAhWOLDE GEBRIEl, @' Elh ,pion Roods Authority LJirecror General FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA ETHIOPIAN ROADS AUTHORITY E1546 v 4 N Y# Dalol W E Y# Kuneba Y# CONSULTANCYBerahile SERVICES S F OR FOR Ab-Ala Y# FEASIBILITY STUDY Y# ENVIRONMENTALAfdera IMPACT ASSESSMENT Megale Y# Y# Didigsala AND DETAILEDYalo ENGINEERING DESIGN Y# Y# Manda Y# Sulula Y# Awra AND Y# Serdo Y# TENDEREwa DOCUMENT PREPARATIONY# Y# Y# Loqiya Hayu Deday -

Final MARD Thesis

School of Continuing Education Analysis of the impact of household’s access to irrigation facilities on improving household’s food security in Ethiopia: The case of Raya-Azebo Woreda, Tigray Region, Ethiopia A Thesis submitted to the School of Continuing Education Indira Gandhi National Open University Maidan Garhi, New Delhi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts in Rural Development (MARD) By Haileselassie Gebremedhin November, 2013 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia i Declaration I hereby declare that the Dissertation entitled ‘’ Analysis of the impact of household’s access to irrigation facilities on improving household’s food security in Ethiopia: The case of Raya-Azebo Woreda, Tigray Region, Ethiopia ’’ submitted by me for the partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Rural Development (MARD) to Indira Gandhi National OPEN University (IGNOU) New Delhi is my own original work and has not been submitted to IGNOU or other Institutions for the fulfilment of the requirements of any course of study. I also declare that no chapter of this manuscript in whole or in part is lifted and incorporated in this report from earlier works. Place: Addis Ababa Signature: ________________ Date of submission: ------------------------- Enrolment No. 099122304 Name: Haileselassie Gebremedhin Address: Mobile: 0914728628 E-mail:[email protected] Addis Ababa, Ethiopia ii Acknowledgement First of all, I must thank the almighty God who helped me to bring this work to the end. I feel great pleasure to express my special gratitude to my thesis principal advisor Dr. Mulugeta Taye for his valuable comments and assistance for the development of my questionnaire, proposal and thesis. -

Determinants of Poverty in Rural Ethiopia: Evidence from Tenta Woreda (District), Crossmark Amhara Region

Journal of ArchiveSustainable of SID Rural Development December 2019, Volume 3, Number 1-2 Research Paper: Determinants of Poverty in Rural Ethiopia: Evidence from Tenta Woreda (District), CrossMark Amhara Region Anteneh Silshi Merid1, Daniel Asfaw Bekele2* 1. MSc, Geography and Environmental Studies Department, College of Social Science, Addis Ababa university, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2. MSc, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Social Science College, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia and Member of Geographic Data and Technology Center of Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Use your device to scan and read the article online Citation: Silshi Merid, A., & Asfaw Bekele, D. (2019). Determinants of Poverty in Rural Ethiopia: Evidence from Ten- ta Woreda (District), Amhara Region. Journal of Sustainable Rural Development, 3(1-2), 3-14. https://doi.org/10.32598/ JSRD.02.02.40 : https://doi.org/10.32598/JSRD.02.02.40 Article info: A B S T R A C T Received: 26 Mar. 2019 Accepted: 12 Agu. 2019 Purpose: Poverty is a challenge facing all countries but worst in Sub-Sahara African. Ending poverty in its all form is the Nation’s 2030 core goals where Ethiopia is striving. Therefore, to step forward the effort, it is necessary to assess rural poverty. Accordingly, the study intended to investigate the determinants of rural poverty at the household level in Tenta district, South Wollo Zone. Methods: A mixed research design is employed to frame the study and 196 representative samples are identified using a multistage sampling technique from three agroecological zones. Primary data are collected through a detailed structured household survey which involves questionnaires, semi- structured interview and FGD techniques. -

Using a Geographical Information System Within the BASIS Research Program in Ethiopia

Using a Geographical Information System within the BASIS Research Program in Ethiopia A report prepared for the Institute for Development Anthropology (IDA) under the BASIS/Institute for Development Research (IDR) program for Ethiopia Report prepared by: Michael Shin, Ph. D. Department of Geography and Regional Studies University of Miami Table of Contents 1 Levels of Analysis and the South Wollo 1 2 Spatial Analysis in the South Wollo 5 3 Data Issues within the South Wollo 7 References 9 Appendix A: Trip Report for Michael Shin 10 1 This report provides a preliminary account of how a geographical information system (GIS) can be integrated within the BASIS research program in Ethiopia, and provides recommendations for its development and use. Part I shows how data from different levels of analysis, and diverse sources, are integrated into a comprehensive food security database for the South Wollo. Spatial analyses which can be used to organize, inform and extend the on-going market surveys and market inventories in the South Wollo are illustrated in Part II, and the final section provides suggestions for future data collection efforts. Data for this report were collected by Dr. Michael Shin during his visit to Ethiopia between 27 July 1999 and 7 August 1999, which was shortened by approximately one week due to inclement weather and sporadic travel times. Presentation graphics within this report were created with the ArcView (version 3.1) GIS distributed by Environmental Systems Research, Incorporated, and MacroMedia FreeHand (version 8.0.1) graphic design software. Due to high start-up costs, both financially and in terms of technical capacity building which are documented in Shin (1998), subsequent GIS analyses for the South Wollo food security project should be conducted in the United States.