Changing Contact Patterns Within the Luleå District During the Nineteenth Century Author(S): Ian G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Networks and Alliances

THE CONTEMPORARY ART DAYS SUMMIT 2018 NETWORKS AND ALLIANCES samtidskonstdagarna.se/en 14–16 November 2018 Boden/Luleå 13 November Pre-summit visit to Kiruna The Contemporary Art Days is the annual contemporary art summit that brings together art professionals from across Sweden and other countries to discuss current issues for art organisations. In 2018, for the first time, the summit is organised under the aegis of the Public Art Agency Sweden. This year’s summit will focus on building networks and alliances as strate- gies for action in contemporary art organisations today. The last few years have witnessed a large increase in organisational networks across the art field in Sweden. Whether formal or informal, on a local or national scale, with Nordic or international counterparts, alliances are formed in a variety of constellations between art institutions, self-organised initiatives and other organisations. Are these networks signs of the signature strategy of the neoliberal working world? Or are they responses of mutual support and solidarity by small and mid-size art organisations in the changing political landscape and precarious economic conditions? Or are today’s networks merely new forms of age old tools for building assemblies around mutual concerns? The Contemporary Art Days 2018 presents a diverse programme comprising guest speakers, performances, site visits and workshops that will examine a variety of ways of working with networks and building strategic alliances. The summit is held in the region of Norrbotten in the north of Sweden. A preview of the 2018 Luleå Biennial is included in the programme, as well as a pre-summit site visit to Kiruna, a mining town that is being relocated and rebuilt. -

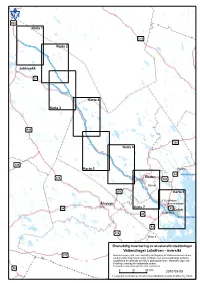

Lulealven.Pdf

± E45 Karta 1 E10 Karta 2 Jokkmokk 97 Karta 4 Karta 3 E45 356 Karta 6 E45 Karta 5 Råneå E4 Rånefjärden Boden 374 383 Sävast 356 Karta 8 S Sunderbyn Älvsbyn Gammelstaden Karta 7 94 97 Luleå Bergnäset 94 Brändöfjärden E4 374 Rosvik Kallfjärden Översiktlig inventering avStorfjärden erosionsförutsättningar Vattendraget Luleälven - översikt 373 Redovisningen ingår i en översiktligPiteå kartläggning av stranderosionen utmed landets vattendrag.Bergsviken Kartan visar områden med erosionskänsliga jordarter. Uppgifterna är baserade på SGU:s geologiska kartor. Materialet utgör inte tillräckligt underlag för detaljerade studier. Eventuella erosionsskydd har inte inventerats. 95 0 10 20 Km Bondöfjärden2010-09-09 © Copyright Lantmäteriet. Ur GSD-Översiktskartan ärende nr MS2010_10049 Översiktlig inventering av erosionsförutsättningar ± Vattendraget Luleälven - karta 1 Redovisningen ingår i en översiktlig kart- Teckenförklaring läggning av stranderosionen utmed landets vattendrag. Kartan visar områden med Grovsand-finsand erosionskänsliga jordarter. Uppgifterna är Silt baserade på SGU:s geologiska kartor. Materialet utgör inte tillräckligt underlag Svämsediment för detaljerade studier. Fyllning Eventuella erosionsskydd har inte inventerats. Tätort >200 invånare 0 1 2 3 4 Km 2010-09-09 © Copyright Lantmäteriet. Ur GSD-Översiktskartan ärende nr MS2010_10049 E45 Lu leälven Översiktlig inventering av erosionsförutsättningar ± Vattendraget Luleälven - karta 2 Redovisningen ingår i en översiktlig kart- Teckenförklaring läggning av stranderosionen utmed landets -

Lifeblood Then and Now the Area of Edefors, Or Edeforsen (Ede Ra- Luleå Came from Salmon Fishing in Edefors

Edefors Edefors – Lifeblood then and now The area of Edefors, or Edeforsen (Ede Ra- Luleå came from salmon fishing in Edefors. Med den här informations- pids) as it was known before the river was Every now and then, two tons of salmon samlingen av besöksmålen dammed and the rapids disappeared, has a were caught here, in a single day. i Edeforsområdet vill vi göra history that goes a long way back. The place Edefors has also been the site of an iron kunskapen och historien has been part of a transportation route for mill, log driving, the construction of an Eng- levande och tillgänglig även centuries, with silver, salmon, logs, tar and lish canal built by over 1400 workers, who digitalt och för dig som är passenger boats passing through. There came to join Sweden’s first workers’ riots, are remains from all kinds of activities from which ended up requiring military interven- här på besök, vill söka fakta different eras. Stone Age dwellings, cooking tion. There are many mythicals tales about eller berätta för dina gäster pits, fishermen’s sheds from the 18th cen- this place and still to this day, people speak om det som har hänt här. tury, a stone labyrinth, foundation remains of a silver treasure left behind. of a market square and workers’ houses, re- mains of a canal, a stone pier and a blast fur- The area was also visited by celebrities of nace ruin. There are also aquatic structures, the time. Carl Linnaeus, the scientist who remains of the log driving era. The Edefors amongst many other things created the area is home to easily accessible, well-pre- foundation for modern systematic classi- served examples of remains from various li- fication of flora and fauna, came here and velihoods that were important in the region documented the fishing and local life in his at different points in history. -

Church Village of Gammelstad, Luleå

WORLD HERITACE LIST cammelstad NO 762 Identification Nomination The church village of Gammelstad, Lulea Location county of Norrbotten <Norrbottens lan> state Party sweden Date 23 October 1995 Justification by State Party Lulea Gammelstad is of international importance as the foremost representative of scandinavia's church towns, a type of town-like milieu that has been shaped bY people's religious and social needs rather than by economie and geographical forces, being intended for use only during weekends and church festivals. lt represents a type of Nordic settlement that has nearly disappeared. lt combines rural and urban life in a remarkable way. The custom of staying close to the church throughOut the weekend has created a way of life and style of building whose main features have been preserved unchanged for four hundred years. lt is considered to conform with criteria ii, iv, anCI v. category of propertv ln terms of the categories of property set out in Article 1 of the 1972 world Heritage convention, Gammelstad is a group of buildings. Historv anCI Description History The Lule river and its valley have provided an effective route between the Gulf of Bothnia and the mountains of Lapland, and beyond to the coast of northern Norway, from earliest times. Agricultural villages had been established on the fertile lands along the coast and in the lower portion of the river valley as early as the 13th centurv. A market centre developed on the islands in the Lulea district in the 14th centurv. When the swedish Finnish kingdom, supported by the Archbishop of uppsala, expanded into this region as an act of deliberate colonization, to counteract Russian pressure, the present stone church of Gammelstad was built at the turn of the 1Llth centurv. -

Kvinner Og Natur

Women and Natural Resource Management in the Rural North Arctic Council Sustainable Development Working Group 2004-2006 By Lindis Sloan (ed) Joanna Kafarowski Anna Heilmann Anna Karlsdóttir Bente Aasjord Maria Udén May-Britt Öhman Nandita Singh Sanna Ojalammi Women and Natural Resource Management in the Rural North Arctic Council Sustainable Development Working Group 2004-2006 By Lindis Sloan (ed) Joanna Kafarowski Anna Heilmann Anna Karlsdóttir Bente Aasjord Maria Udén May-Britt Öhman Nandita Singh Sanna Ojalammi Published by Forlaget Nora Kvinneuniversitetet Nord N-8286 Nordfold Layout: Pure Line Design, Nordfold. www.PureLine.Norge.cc Cover photo: International Steering Committee member Lene Kielsen Holm on the lulissat ice fjord, June 2006. Photo: Anna Heilmann. ISBN: 82-92038-02 Contents Preface . 7 Concluding remarks from the project work group and international steering committee . 9 A human security perspective . 10 Women and Natural Resource Management in the Rural North . 12 Project summaries . 17 Canada . 19 Greenland . 37 Iceland . 73 Norway . 97 Sweden . 129 Finland . 155 5 6 Preface “Women and Natural Resource Management “Management of natural, including living, in the Rural North” is a continuation of the resources”. Analysing natural resource-based 2003-2004 Arctic Council SDWG project industries in the Arctic in terms of women’s “Women’s participation in decision-making participation in these sectors covers both processes in Arctic fisheries resource manage- these points. ment”, which presented its report to the Developing prosperous and resilient local Ministers in Reykjavik. communities depends on achieving social sustainability, including economic activities The “Women and Natural Resource in the primary, secondary and tertiary sectors. -

The Economical Geography of Swedish Norrland Author(S): Hans W:Son Ahlmann Source: Geografiska Annaler, Vol

The Economical Geography of Swedish Norrland Author(s): Hans W:son Ahlmann Source: Geografiska Annaler, Vol. 3 (1921), pp. 97-164 Published by: Wiley on behalf of Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/519426 Accessed: 27-06-2016 10:05 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography, Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Geografiska Annaler This content downloaded from 137.99.31.134 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 10:05:39 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE ECONOMICAL GEOGRAPHY OF SWEDISH NORRLAND. BY HANS W:SON AHLMrANN. INTRODUCTION. T he position of Sweden can scarcely be called advantageous from the point of view of commercial geography. On its peninsula in the north-west cor- ner of Europe, and with its northern boundary abutting on the Polar world, it forms a backwater to the main stream of Continental communications. The southern boundary of Sweden lies in the same latitude as the boundary between Scotland and England, and as Labrador and British Columbia in America; while its northern boundary lies in the same latitude as the northern half of Greenland and the Arctic archipelago of America. -

Fishing in Luleå

SWEDISHthe destinations of LAPLAND YOUR ARCTIC DESTINATION Fishing luck in Luleå Helena Holm Helena Photo: ALWAYS A FISHING WATER WITHIN REACH The summer sun sets down by the restaurants of University, among other things. Today, fishing on the river is not what Luleå’s north harbour. You order a classic Kalix it once was, although salmon and trout are still caught here. However, there are even better opportunities to catch pike and perch. If you are vendace roe starter, to celebrate something. The looking for a wild salmon river, the Råne River is a beautiful option, waiter tells you that you can also order fried also offering magnificent pike fishing, and opportunities to catch wild vendace today, known in Finnish as muikku, river crayfish in the autumn. Around the city of Luleå, you will find and something of a national dish. The vendace, many well maintained fishing waters, both for families and enthusi- Coregonus albula in Latin, is a small salmonid asts. Lake Hertsöträsket has been adapted for accessibility, to provide a good fishing experience even for those in wheelchairs. Luleå was not fish which gives us the amazing vendace roe, and just founded on fish, it is also a place for those who like to fish. Just as also Norrbotten’s official county fish. Since 2010, you could expect from a city on the coast of the Gulf of Bothnia. Kalix vendace roe has been an item with protected designation of origin, such as Parma ham, Stilton good to know Carefully check that you are fishing on licenced waters, cheese and champagne. -

Läs Hela Analysen

Bostadsförsörjningsanalys Luleå December 2020 Linda Lövgren, Maria Pleiborn, Ebba Älvgren Förord Syftet med analysen att analysera och bedöma det kommande behovet av bostäder för Luleå kommun och vilken typ av bostäder som kommer att efterfrågas med avseende på de målgrupper som är aktuella. Analysen är en grund till riktlinjerna för bostadsförsörjning och innehåller en analys av kommunens demografiska utveckling, efterfrågan på bostäder, bostadsbehovet för särskilda grupper och marknadsförutsättningarna för bostäder totalt sett samt för kommunens delområden. Analysen har även kopplats till bostadsmarknadsläget i grannkommunerna och den regionala bostads- och arbetsmarknaden i stort. 2 Författare: Linda Lövgren, Maria Pleiborn och Ebba Älvgren. Stockholm, december 2020 WSP Sverige AB SE-121 88 Stockholm-Globen Arenavägen 7 Org. nr: 556057-4880 Innehåll — Slutsatser och åtgärdsförslag för bostadsmarknaden i Luleå kommun — Allmänt om bostadsmarknaden i Sverige — Omvärldsanalys — Demografisk analys — Bostadsbestånd och nyproduktion 3 — Bostadssituationen för särskilda grupper — Efterfrågan på bostäder — Geografisk analys Slutsatser Luleå är en kommun med en stabil Däremot är efterfrågan oftast på bostäder befolkningsökning och en förhållandevis som är billigare än vad marknaden förmår låg arbetslöshet. Luleå kommun har i stort att producera. Detta leder till att en hög sett en god bostadsförsörjning i nuläget grad av exploatering inte leder till en bättre och det finns ingen underliggande bostadsförsörjning i kommunen. strukturell bostadsbrist. Däremot är en god planeringsberedskap Däremot finns ett behov av bostäder med alltid positiv, eftersom det ger flexibilitet i 4 en lägre prisnivå än vad marknaden förmår planeringen. att producera redan hos den existerande befolkningen. En övervägande andel av de nya invånarna är invandrare, som oftast har en något lägre betalningsförmåga. -

Scandinavia and Arctic 2020

SCANDINAVIA AND ARCTIC 2020 NORWAY SWEDEN DENMARK FINLAND BALTICS RUSSIA ICELAND FAROE ISLANDS GREENLAND SPITSBERGEN www.nordictravel.com.au [email protected] 1300 702 833 (02) 9904 5424 Iceland driving distances Greenland flight times Keflavík Airport – Reykjavík 55km Narsarsuaq – Nuuk 1hr 15mins Reykjavík – Isafjörður 388km Nuuk – Kangerlussuaq 55mins Isafjörður – Akureyri 513km Kangerlussuaq – Ilulissat 45mins Akureyri – Husavík 90km Ilulissat – Narsarsuaq 5hrs 55mins Husavík – Seyðisfjörður 245km Seyðisfjörður – Höfn 212km Höfn – Vík 272km Vík – Selfoss 129km Selfoss – Blue Lagoon 90km Blue Lagoon – Keflavík Airport 18km GREENLAND Hólmavík • • Akureyri Varmahlíð • Lake Mývatn • Seyðisörður Egilsstaðir • • • Stykkisholmur Uummannaq ICELAND • • Illulissat Reykholt • Aasiaat • Borgarnes Sisimiut • Geysir Gullfoss Vatnajökull • Kangerlussuaq •• • Höfn • Reykjavík þingvellir • Maniitsoq • • Jökulsárlón • • Kulusuk Keavík Skaftafell • • • • Hveragerði • Nuuk Kirkjubæjarklaustur Paamiut • • Narsarsuaq Seljalandsfoss Narsaq • • 50km • 500km Skógafoss • • Vík Qaqortoq• Faroe Islands driving distances Vágar Airport – Tórshavn 47km SPITSBERGEN Tórshavn – Kirkjubøur 11km Tórshavn – Klaksvík 75km Tórshavn – Gjógv 64km Ferries Tórshavn – Vestmanna 39km Helsinki to St Petersburg Klaksvík – Kunoy 12km Helsinki to Tallinn Klaksvík – Viðareiði 19km Helsinki to Stockholm Copenhagen to Oslo Ferries and sub-Sea tunnels Viðareiði Mikladalur • Bergen to Kirkenes (which is the Hurtigruten coastal ferry route) Sørvágur to Mykines Gjógv • • North Cape -

Assessment of the Potential Amount of Floating Debris in Lule River

2008:072 PB MASTER’S THESIS Assessment of the potential amount of floating debris in Lule river Assessment of the potential amount of floating debris in Lule river René Minarski Master of science program Luleå University of technology Department civil, miningRené and Minarski environmental engineering Division of mining and geotechnical engineering M.Sc. in Mining and Geotechnical Engineering CONTINUATION COURSES Luleå University of Technology Department of Civil, Mining and Environmental Engineering Division of Mining and Geotechnical Engineering 2008:072 PB • ISSN: 1653 - 0187 • ISRN: LTU - PB - EX - - 08/072 - - SE Assessment of the potential amount of floating debris in Lule river René Minarski Master of science program Luleå University of technology Department civil, mining and environmental engineering Division of mining and geotechnical engineering Räddningsverket har äganderätten till den översiktliga stabilitetskarteringen som använts som bakgrundsmaterial till detta examensarbete. Att mångfaldiga innehållet i denna dokumentation, helt eller delvis, utan medgivande av Räddningsverket är förbjudet enligt lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk. Förbudet gäller varje mångfaldigande genom tryckning, kopiering, digital bearbetning etc. Räddningsverket har nyttjanderätt till resultatet av examensarbetet. - I - PREFACE PREFACE Already while I was studying for my Bachelors degree at the University of Göttingen in Germany I had made up my mind that I want to continue studying in an international M.Sc. program, even though I was the only student in a grade of approximately 35 students that decided to go into that direction. By gaining a Masters degree in a program taught in English and outside of my home country I wanted to increase my chances on the international job market. -

A World Heritage Site As Arena for Sami Ethno-Politics in Sweden

Managing Laponia ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Uppsala Studies in Cultural Anthropology no 47 Carina Green Managing Laponia A World Heritage as arena for Sami ethno-politics in Sweden Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Geijersalen, Thun- bergsväg 3H, Uppsala, Friday, December 18, 2009 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Green, C. 2009. Manging Laponia. A World Heritage Site as Arena for Sami Ethno-Politics in Sweden. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Uppsala Studies in Cultural Anthropology 47. 221 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-554-7656-4. This study deals with the implications of implementing the World Heritage site of Laponia in northern Sweden. Laponia, consisting of previously well-known national parks such as Stora Sjöfallet and Sarek, obtained its World Heritage status in 1996. Both the biological and geological significance of the area and the local Sami reindeer herding culture are in- cluded in the justification for World Heritage status. This thesis explores how Laponia became an arena for the long-standing Sami ethno-political struggle for increased self- governance and autonomy. In many other parts of the world, various joint management schemes between indigenous groups and national environmental protection agencies are more and more common, but in Sweden no such agreements between the Swedish Envi- ronmental Protection Agency and the Sami community have been tested. The local Sami demanded to have a significant influence, not to say control, over the future management of Laponia. These were demands that were not initially acknowledged by the local and national authorities, and the negotiations about the management of Laponia continued over a period of ten years. -

5 Samebyarna E12 EJ�FASTSTËLLD

Konsekvensanalys för rennäringen längs Norrbotniabanan LUOKTA-MÁVAS 45 R ieb n e s -ASKAURESAMEBYSMARKANVËNDNING Råneälven ÄNGESÅ Vännäsberget Tallvik Vuollerim -ASKAURESAMEBY Gyljen S äd vv á jáv rre GÄLLIVRE Överkalix ¿RETRUNTMARKEROVAN 3AMEBY GRËNSBESTËMTOMRÍDE SEMISJAUR-NJARG LAPPMARKSGRËNSEN 3AMEBY EJGRËNSBESTËMTOMRÍDE Hednäset 'RUVA,AISVALL Svartbyn 97 /DLINGSGRËNS .YLIGENSTËNGD E10 H o rn a v an ,APPMARKSGRËNS LIEHITTÄJÄ 4IDIGAREGËLLANDEKONVENTIONSOMRÍDE +ËRNOMRÍDE6ËSTRA5DDJAUR 3TËNGSELINOMSAMEBYNSMARKER Karungi 6INTERBETESMARKERNEDAN Morjärv H o rn a v an STÅKKE 3AMLINGSPLATSINFÚRHÚSTFLYTTNINGUDTJA LAPPMARKSGRËNSEN KALIX +ËRNOMRÍDEAVRIKSINTRESSEGunnarsbyn SVAIPA LuleälvenBoträskfors Laisvall Harads 6ÍRLAND /MRÍDEANVËNDSAV L aisa n A jsjáv rre LUOKTA-MÁVAS (ÚSTLAND Svartlå -ASKAUREOCH3VAIPA Arjeplog 3OMMARLAND Töre Kalix Sangis SAMEBYAR U d d jau re 6INTERLAND E4 Råneå /MRÍDEMEDANNANKONKURRERANDE Rolfs Bredviken Vittjärv Risögrund 3VÍRTOMRÍDEMEDBLAMINERALPROSPEKTERINGAR MARKANVËNDNINGB o d e n Påläng Båtskärsnäs GRAN VÄSTRA KIKKEJAURE Piteälven Karlsborg NEDLAGDA+EDTRËSK OCH¿SENGRUVAN Vidsel /MRÍDEANVËNDSAVFLERASAMEBYARB o c kö fjä rd e n Nyborg Moskosel Sävast Seskarö Ängesbyn 0 20 Persön40 Laisälven Unbyn Km Brändön © Lantmäteriet 2001. SUrS GSD-ÖVERS,underbyn Rutvik Dnr: M2001/1502. SEMISJAUR-NJARG Älvsbyn Gammelstaden Vistheden Karlsvik Bensbyn S to ra va n Bälinge Luleå 94 Klöverträsk Bergnäset Tärnaby Korsträsk RAN 94 Alvik Antnäs Arvidsjaur Ersnäs Kallax ÖSTRA KIKKEJAURE Måttsund E45 Sjulsmark +ËRNOMRÍDE6EDDEK +ORSTRËSK +ËRNOMRÍDE'UMMARK