GARDENS and LANDSCAPES - Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Trends in Green Urbanism and Peculiarities of Multifunctional Complexes, Hotels and Offices Greening

Ukrainian Journal of Ecology Ukrainian Journal of Ecology, 2020, 10(1), 226-236, doi: 10.15421/2020_36 REVIEW ARTICLE UDK 364.25: 502.313: 504.75: 635.9: 711.417.2/61 Current trends in Green Urbanism and peculiarities of multifunctional complexes, hotels and offices greening I. S. Kosenko, V. M. Hrabovyi, O. A. Opalko, H. I. Muzyka, A. I. Opalko National Dendrological Park “Sofiyivka”, National Academy of Science of Ukraine Kyivska St. 12а, Uman, Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: 10.02.2020 Accepted 06.03.2020 The analysis of domestic and world publications on the evolution of ornamental garden plants use from the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and ancient Romans to the “dark times” of the middle Ages and the subsequent Renaissance was carried out. It was made in order to understand the current trends of Green Urbanism and in particular regarding the diversity of floral and ornamental arrangements used in the design of modern interiors of public spaces. The aim of the article is to grasp current trends of Green Urbanism regarding the diversity of floral and ornamental arrangements used in the design of modern interiors of public premises. Cross-cultural comparative methods have been used, partially using the hermeneutics of old-printed texts in accordance with the modern system of scientific knowledge. The historical antecedents of ornamental gardening, horticulture, forestry and vegetable growing, new trends in the ornamental plants cultivation, modern aspects of Green Urbanism are discussed. The need for the introduction of indoor plants in the residential and office premises interiors is argued in order to create a favorable atmosphere for work and leisure. -

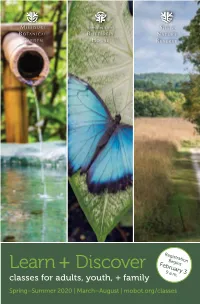

Learn + Discover February 3 9 A.M

ADULT CLASSES | DIY CRAFTS CLASSES | DIY ADULT Registration Begins Learn + Discover February 3 9 a.m. classes for adults, youth, + family Spring–Summer 2020 | March–August | mobot.org /classes Registration starts February 3 at 9 a.m.! Sign up online at mobot.org/classes. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE CRAFTS CLASSES | DIY ADULT Offered for a diversity of learners, from young explorers to budding enthusiasts Your love for plants to skilled gardeners, our courses have been expertly designed to educate, can change the world. inspire, and enrich. Most importantly, they are intended to strengthen the connections each of us has with the natural world and all its wonders. Whether you’re honing your gardening skills, flexing your Come grow with us! creativity, or embracing your inner ecologist, our classes equip you to literally transform landscapes and lives. And you thought you were just signing up for a fun class. SITE CODES How will you discover + share? Whether you visit 1 of our 3 St. Louis MBG: Missouri Botanical Garden area locations with family and friends, SNR: Shaw Nature Reserve enjoy membership in our organization, BH: Sophia M. Sachs Butterfly House take 2 of our classes, or experience a off-site: check class listing special event, you’re helping save at-risk species and protect habitats close to home and around the world. © 2020 Missouri Botanical Garden. On behalf of the Missouri Botanical Printed on 30% post-consumer recycled paper. Please recycle. Garden and our 1 shared planet… thank you. Designer: Emily Rogers Photography: Matilda Adams, Flannery Allison, Hayden Andrews, Amanda Attarian, Kimberly Bretz, Dan Brown, “To discover and share knowledge Kent Burgess, Cara Crocker, Karen Fletcher, Suzann Gille, Lisa DeLorenzo Hager, Elizabeth Harris, Ning He, Tom about plants and their environment Incrocci, Yihuang Lu, Jean McCormack, Cassidy Moody, in order to preserve and enrich life.” Kat Niehaus, Mary Lou Olson, Rebecca Pavelka, Margaret Schmidt, Sundos Schneider, Doug Threewitt, and courtesy —mission of the Missouri Botanical Garden of Garden staff. -

Greenwashed: Identity and Landscape at the California Missions’

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUPUIScholarWorks ‘GREENWASHED: IDENTITY AND LANDSCAPE AT THE CALIFORNIA MISSIONS’ Elizabeth KRYDER-REID Indiana University, Indianapolis (IUPUI), 410 Cavanaugh Hall, 425 University Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 56202, USA [email protected] Abstract: This paper explores the relationship of place and identity in the historical and contemporary contexts of the California mission landscapes, conceiving of identity as a category of both analysis and practice (Brubaker and Cooper 2000). The missions include twenty-one sites founded along the California coast and central valley in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The missions are all currently open to the public and regularly visited as heritage sites, while many also serve as active Catholic parish churches. This paper offers a reading of the mission landscapes over time and traces the materiality of identity narratives inscribed in them, particularly in ‘mission gardens’ planted during the late 19th and first half of the 20th century. These contested places are both celebrated as sites of California's origins and decried as spaces of oppression and even genocide for its indigenous peoples. Theorized as relational settings where identity is constituted through narrative and memory (Sommers 1994; Halbwachs 1992) and experienced as staged, performed heritage, the mission landscapes bind these contested identities into a coherent postcolonial experience of a shared past by creating a conceptual -

Medieval Monastery Gardens in Iceland and Norway

religions Article Medieval Monastery Gardens in Iceland and Norway Per Arvid Åsen Natural History Museum and Botanical Garden, University of Agder, 4604 Kristiansand, Norway; [email protected] Abstract: Gardening was an important part of the daily duties within several of the religious orders in Europe during the Middle Ages. The rule of Saint Benedict specified that the monastery should, if possible, contain a garden within itself, and before and above all things, special care should be taken of the sick, so that they may be served in very deed, as Christ himself. The cultivation of medicinal and utility plants was important to meet the material needs of the monastic institutions, but no physical garden has yet been found and excavated in either Scandinavia or Iceland. The Cistercians were particularly well known for being pioneer gardeners, but other orders like the Benedictines and Augustinians also practised gardening. The monasteries and nunneries operating in Iceland during medieval times are assumed to have belonged to either the Augustinian or the Benedictine orders. In Norway, some of the orders were the Dominicans, Fransiscans, Premonstratensians and Knights Hospitallers. Based on botanical investigations at all the Icelandic and Norwegian monastery sites, it is concluded that many of the plants found may have a medieval past as medicinal and utility plants and, with all the evidence combined, they were most probably cultivated in monastery gardens. Keywords: medieval gardening; horticulture; monastery garden; herb; relict plants; medicinal plants Citation: Åsen, Per Arvid. 2021. Medieval Monastery Gardens in 1. Introduction Iceland and Norway. Religions 12: Monasticism originated in Egypt’s desert, and the earliest monastic gardens were 317. -

And Seventeenth-Century Native American and Hispanic Transformations of the Georgia Bight Landscapes

Bull. Fla. Mus. Nat. Hist. (2003) 44(1) 183-198 183 IMAGINING SIXTEENTH- AND SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NATIVE AMERICAN AND HISPANIC TRANSFORMATIONS OF THE GEORGIA BIGHT LANDSCAPES Donna L. Ruhl' Various subfields of archaeology, including archaeobotany, zooarchaeology, archaepedology, and bioarchaeology, are interrelated in this essay to provide a provisional look at the interactions between humans, both Native American and European, and the environment that impacted the landscape and land use reconstruction. Focusing on the archaeobotany of both precontact sites andsixteenth- and seventeenth-century mission-period sites along coastal La Florida, Native American and Spanish use of and impact on the plants and land of the Georgia Bight reveal many transformations. Areas of the landscape were altered in part by Hispanic introductions, including architecture and agrarian practices that invoked not only a difference in degree, but, in some cases, in kind that persist to the present. These changes, however, had far less impact than subsequent European introductions would bring to this region of the.Georgia Bight and its adjacent area. Key words: archaeobotany, Georgia Bight, landscape archaeology, Native American settlement, Spanish settlement Reconstructing landscapes from the archaeological the emergent field of environmental archaeology can record is complex because landscape transformations offer, I selected the lower Atlantic coast for two reasons. minimally entail intentional constructs of buildings and First, much zooarchaeological research has been land use (gardens, fields, roads, pathways, tree plantings, generated in Elizabeth S. Wing's laboratory from this and the like), incidental and accidental human region. Second, for more than a decade archaeobotanical manipulation, and such natural phenomena as floods, research has been encouraged by and has benefited from droughts, and high winds (Ashton 1985; Beaudry 1986; Dr. -

Sourcebookforgardenarchaeologyaddressestheincreasingneed Hopes Toencouragedevelopmentofnewdirectionsforthefuture

Parcs et Jardins 1 Parcs et Jardins Parcs et Jardins 1 SOURCEBOOK The sourcebook for Garden Archaeology addresses the increasing need FOR GARDEN ARCHAEOLOGY among archaeologists, who discover a garden during their own excavation project, for advice and update on current issues in garden archaeology. It Edited by Amina-Aïcha Malek also aims at stimulating broader interest in garden archaeology. Archaeologists with no specifi c training in garden archaeology will read about specifi c problems of soil archaeology with a handful of well-developed techniques, critical discussions and a number of extremely different uses. Methods are described in suffi cient detail for any archaeologist to engage into fi eld work, adapt them to their own context and develop their own methodology. While the Sourcebook aims at bringing together different disciplines related to garden archaeology and providing an overview of present knowledge, it also hopes to encourage development of new directions for the future. FOR GARDEN ARCHAEOLOGY Amina-Aïcha MALEK is researcher at the CNRS laboratory «Archéo- logies d’Orient et d’Occident et textes anciens» (AOROC) of the École Normale Supérieure (UMR 8546 CNRS-ENS) in Paris, France. Special Garden Archaeo-logy Fellow at Dumbarton Oaks from 1999 to 2002, she has collaborated to several garden excavations, such as the Petra Pool SOURCEBOOK and Garden Project in Jordan, and the garden at the Villa Arianna in Sta- biae and the garden of Horace’s Villa in Licenza, Italy. She is co-founder and current vice-chair of the Society for -

Byzantine Garden Culture

Byzantine Garden Culture Byzantine Garden Culture edited by Antony Littlewood, Henry Maguire, and Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 2002 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Byzantine garden culture / edited by Antony Littlewood, Henry Maguire and Joachim Wolschke- Bulmahn. p. cm. Papers presented at a colloquium in November 1996 at Dumbarton Oaks. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) ISBN 0-88402-280-3 (alk. paper) 1. Gardens, Byzantine—Byzantine Empire—History—Congresses. 2. Byzantine Empire— Civilization—Congresses. I. Littlewood, Antony Robert. II. Maguire, Henry, 1943– III. Wolschke- Bulmahn, Joachim. SB457.547 .B97 2001 712'.09495—dc21 00-060020 To the memory of Robert Browning Contents Preface ix List of Abbreviations xi The Study of Byzantine Gardens: Some Questions and Observations from a Garden Historian 1 Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn The Scholarship of Byzantine Gardens 13 Antony Littlewood Paradise Withdrawn 23 Henry Maguire Byzantine Monastic Horticulture: The Textual Evidence 37 Alice-Mary Talbot Wild Animals in the Byzantine Park 69 Nancy P. Sevcenko Byzantine Gardens and Horticulture in the Late Byzantine Period, 1204–1453: The Secular Sources 87 Costas N. Constantinides Theodore Hyrtakenos’ Description of the Garden of St. Anna and the Ekphrasis of Gardens 105 Mary-Lyon Dolezal and Maria Mavroudi Khpopoii?a: Garden Making and Garden Culture in the Geoponika 159 Robert Rodgers Herbs of the Field and Herbs of the Garden in Byzantine Medicinal Pharmacy 177 John Scarborough The Vienna Dioskorides and Anicia Juliana 189 Leslie Brubaker viii Contents Possible Future Directions 215 Antony Littlewood Bibliography 231 General Index 237 Index of Greek Words 260 Preface It is with great pleasure that we welcome the reader to this, the first volume ever put together on the subject of Byzantine gardens. -

The Hortulus

The Hortulus June 5, 2018 | 1 The Hortulus In the Bishop’s Garden, west of the rose garden and northeast of Shadow House is the Hortulus – or “diminutive garden”. Bordered by boxwood, this little garden features geometric beds planted with monastic kitchen and infirmary and herbs used in the 9th century. Documents from the time of Charlemagne were used as the primary source for this planting. Today, the Hortulus in the Bishop’s Garden includes mint, sages, fennel, rosemary and other fragrant flowery herbs. | 2 The Hortulus Betony in bloom in front of the Carolingian Font The focal point of the Hortulus is the Carolingian Font – surrounded by rosemary. The font is attributed the ninth century AD and is reported to have come from the Abbey of St. Julie in the Aisne. The top is marble and the pedestal is of Caen limestone. It was an | 3 The Hortulus acquisition from the collection of George Grey Barnard and donated to the garden in 1927 by Mrs. Henry Hudson Barton of Philadelphia – in memory of her husband. | 4 The Hortulus | 5 The Hortulus Chives are one of the herbs growing in the Hortulus The overall inspiration for the Bishop’s Garden is a 14th century monastic garden, in keeping with the gothic design of the Cathedral. However, this small garden room, the Hortulus, is anchored firmly in the 9th century. In his poem entitled “Hortulus”, written in 849 A. D., Abbot Walahfrid Strabo describes how some of the plants included in this little garden would have been used during his time. -

Clwyd Branch News September 2009

YMDDIRIEDOLAETH GERDDI HANESYDDOL CYMRU . WELSH HISTORIC GARDENS TRUST Clwyd Branch News September 2009 Wenlock Priory and Windy Ridge Oct 10th Wenlock Priory, Lavabo in cloister, Much Wenlock, Shropshire. V. J. de la Haye. Lantern Slide. Shrewsbury Museums Service (SHYMS: P/2005/0414). Image sy9257 Wenlock Priory is the ruin of the largest Cluniac Ab- avoided damaging the local crops when she spoke bey built in Britain, re-founded in 1079 by the Nor- to them. In art, Saint Milburga holds the abbey of man Earl Roger de Montgomery. The abbey took Wenlock, and sometimes geese are near her. over forty years to build. It was heavily endowed Wenlock priory has an interesting lavabo in the with timber from the royal forests by Henry III, a cloister garth. Originally housed inside an octago- regular visitor to Wenlock. nal building, this was where up to 16 monks made An earlier Anglo-Saxon Abbey had been founded their ritual ablutions. The three tiered marble foun- on this site in 680 by the convert King Merewald tain has an early central column, encircled by later of Mercia and his wife St Ermenburga. His daugh- masonry with C12th carvings, supporting a circular ter, Princess Milburga, the second abbess for over trough. Water for the lavabo supplied from Milbur- 30 years was canonised for performing miracles ga’s Well was said to cure sore eyes. including levitation. The elaborate and intricate designs of the Cluniac Originally a double monastery comprising communi- order are seen in the Chapter House with a beauti- ties of men and women, the nunnery was destroyed ful length of interlaced blind arcading with its richly by the Danes circa 878. -

The Icelandic Medieval Monastic Garden – Did It Exist?

This article was downloaded by: [Steinunn Kristjánsdóttir] On: 08 November 2014, At: 01:23 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Scandinavian Journal of History Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/shis20 The Icelandic medieval monastic garden - did it exist? Steinunn Kristjánsdóttir, Inger Larsson & Per Arvid Åsen Published online: 05 Nov 2014. To cite this article: Steinunn Kristjánsdóttir, Inger Larsson & Per Arvid Åsen (2014) The Icelandic medieval monastic garden - did it exist?, Scandinavian Journal of History, 39:5, 560-579, DOI: 10.1080/03468755.2014.946534 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2014.946534 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Royal and the Monastic Gardens at Sigiriya And

CHAPrERONE Senake Bandaranayake Sri Lankais perhaps theonly country in concentrate on religious or philosophi- South Asia where we still have substan- cal pursuits. tial archaeological remains of fonnally- The Sri Lankan chronicles echo laid out royal and monastic gardens Buddhist canonicalliterature in refer- dating from a period before A.D. 1000. ring to royal and suburban parks and They belong to a tradition of garden woods donated by the flrst Buddhist architecture and planning that is well- kings as sites for the early monasterles documented from the late I st millenium {Mahavamsa XV, 1-25). This is con- B. C. onwards. firmed by the archaeological evidence Literary references which shows the city of Anùradhapura The royal and monastic gardens of the ringed by well-planned monastic com- ~ Early and Middle Historical Period (3rd plexes in which parkland, trees and century B.C. to 13th century A.D.) are water clearly played an important role referred to in the B uddhist chronicles of (Silva, 1972; Bandaranayake, 1974: 33 Sri Lanka from as early as the 3rd fr.). century B.C. The chronicles them- The alternative monastery type to selves, of course, were written between the park orgrovemonastery (or 'ararna') the 3rd and Sth century A.D. from ear- was what has been called the 'girl' or lier written and oral sources. Whatever mountain monastery (Basnayake, 1983; the actual history of Sri Lankan garden- see also Bandaranayake, 1974: 33,46, ing may be, the Sri Lankan Buddhists 47). Here, a rocky mountain peak or inhe.rited and developed two concepts slope was selected and caves or rock of the early Indian tradition, which have shelters fashioned from the sides of a direct bearing on the art of site selection massive boulders. -

Western Botanical Gardens: History and Evolution

5 Western Botanical Gardens: History and Evolution Donald A. Rakow Section of Horticulture School of Integrative Plant Science Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Ithaca, NY USA Sharon A. Lee Sharon Lee and Associates Swarthmore, PA USA ABSTRACT Dedicated to promoting an understanding of plants and their importance, the modern Western botanical garden addresses this mission through the establish- ment of educational programs, display and interpretation of collections, and research initiatives. The basic design and roles of the contemporary institution, however, can be traced to ancient Egypt, Persia, Greece, and Rome, where important elements emerged that would evolve over the centuries: the garden as walled and protected sanctuary, the garden as an organized space, and plants as agents of healing. In the Middle Ages, those concepts expanded to become the hortus conclusus, the walled monastery gardens where medicinal plants were grown. With intellectual curiosity at its zenith in the Renaissance, plants became subjects to be studied and shared. In the 16th and 17th centuries, botanical gardens in western Europe were teaching laboratories for university students studying medicine, botany, and what is now termed pharmacology. The need to teach students how to distinguish between medicinally active plants and poisonous plants led the first professor of botany in Europe, Francesco Bonafede, to propose the creation of the Orto botanico in Padua. Its initial curator was among the first to take plant collecting trips throughout Europe. Not to be Horticultural Reviews, Volume 43, First Edition. Edited by Jules Janick. 2015 Wiley-Blackwell. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 269 270 D.