The History and Functions of Botanic Gardens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE SCIENCE IN THE AMERICAN STYLE, 1700 – 1800 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By ROBYN DAVIS M CMILLIN Norman, Oklahoma 2009 SCIENCE IN THE AMERICAN STYLE, 1700 – 1800 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ________________________ Prof. Paul A. Gilje, Chair ________________________ Prof. Catherine E. Kelly ________________________ Prof. Judith S. Lewis ________________________ Prof. Joshua A. Piker ________________________ Prof. R. Richard Hamerla © Copyright by ROBYN DAVIS M CMILLIN 2009 All Rights Reserved. To my excellent and generous teacher, Paul A. Gilje. Thank you. Acknowledgements The only thing greater than the many obligations I incurred during the research and writing of this work is the pleasure that I take in acknowledging those debts. It would have been impossible for me to undertake, much less complete, this project without the support of the institutions and people who helped me along the way. Archival research is the sine qua non of history; mine was funded by numerous grants supporting work in repositories from California to Massachusetts. A Friends Fellowship from the McNeil Center for Early American Studies supported my first year of research in the Philadelphia archives and also immersed me in the intellectual ferment and camaraderie for which the Center is justly renowned. A Dissertation Fellowship from the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History provided months of support to work in the daunting Manuscript Division of the New York Public Library. The Chandis Securities Fellowship from the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens brought me to San Marino and gave me entrée to an unequaled library of primary and secondary sources, in one of the most beautiful spots on Earth. -

Sources and Bibliography

Sources and Bibliography AMERICAN EDEN David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic Victoria Johnson Liveright | W. W. Norton & Co., 2018 Note: The titles and dates of the historical newspapers and periodicals I have consulted regarding particular events and people appear in the endnotes to AMERICAN EDEN. Manuscript Collections Consulted American Philosophical Society Barton-Delafield Papers Caspar Wistar Papers Catharine Wistar Bache Papers Bache Family Papers David Hosack Correspondence David Hosack Letters and Papers Peale Family Papers Archives nationales de France (Pierrefitte-sur-Seine) Muséum d’histoire naturelle, Série AJ/15 Bristol (England) Archives Sharples Family Papers Columbia University, A.C. Long Health Sciences Center, Archives and Special Collections Trustees’ Minutes, College of Physicians and Surgeons Student Notes on Hosack Lectures, 1815-1828 Columbia University, Rare Book and Manuscript Library Papers of Aaron Burr (27 microfilm reels) Columbia College Records (1750-1861) Buildings and Grounds Collection DeWitt Clinton Papers John Church Hamilton Papers Historical Photograph Collections, Series VII: Buildings and Grounds Trustees’ Minutes, Columbia College 1 Duke University, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library David Hosack Papers Harvard University, Botany Libraries Jane Loring Gray Autograph Collection Historical Society of Pennsylvania Rush Family Papers, Series I: Benjamin Rush Papers Gratz Collection Library of Congress, Washington, DC Thomas Law Papers James Thacher -

Document Resume Ed 049 958 So 000 779 Institution Pub

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 049 958 SO 000 779 AUTHCE Nakosteen, Mehdi TITLE Conflicting Educational Ideals in America, 1775-1831: Documentary Source Book. INSTITUTION Colorado Univ., Boulder. School of Education. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 480p. EDES PRICE EDES Price MF-SC.65 HC-$16.45 DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies, Cultural Factors, *Educational History, Educational Legislation, *Educational Practice, Educational Problems, *Educational Theories, Historical Reviews, Resource Materials, Social Factors, *United States History IDENTIFIERS * Documentary History ABSTRACT Educational thought among political, religious, educational, and other social leaders during the formative decades of American national life was the focus of the author's research. The initial objective was the discovery cf primary materials from the period to fill a gap in the history of American educational thought and practice. Extensive searching cf unpublished and uncatalogued library holdings, mainly those of major public and university libraries, yielded a significant quantity of primary documents for this bibliography. The historical and contemporary works, comprising approximately 4,500 primary and secondary educational resources with some surveying the cultural setting of educational thinking in this period, are organized around 26 topics and 109 subtopics with cross-references. Among the educational issues covered by the cited materials are: public vs. private; coed vs. separate; academic freedom, teacher education; teaching and learning theory; and, equality of educational opportunity. In addition to historical surveys and other secondary materials, primary documents include: government documents, books, journals, newspapers, and speeches. (Author/DJB) CO Lir\ 0 CY% -1- OCY% w CONFLICTING EDUCATIONAL I D E A L S I N A M E R I C A , 1 7 7 5 - 1 8 3 1 : DOCUMENTARY SOURCE B 0 0 K by MEHDI NAKOSTEEN Professor of History and Philosophy of Education University of Colorado U.S. -

Current Trends in Green Urbanism and Peculiarities of Multifunctional Complexes, Hotels and Offices Greening

Ukrainian Journal of Ecology Ukrainian Journal of Ecology, 2020, 10(1), 226-236, doi: 10.15421/2020_36 REVIEW ARTICLE UDK 364.25: 502.313: 504.75: 635.9: 711.417.2/61 Current trends in Green Urbanism and peculiarities of multifunctional complexes, hotels and offices greening I. S. Kosenko, V. M. Hrabovyi, O. A. Opalko, H. I. Muzyka, A. I. Opalko National Dendrological Park “Sofiyivka”, National Academy of Science of Ukraine Kyivska St. 12а, Uman, Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: 10.02.2020 Accepted 06.03.2020 The analysis of domestic and world publications on the evolution of ornamental garden plants use from the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and ancient Romans to the “dark times” of the middle Ages and the subsequent Renaissance was carried out. It was made in order to understand the current trends of Green Urbanism and in particular regarding the diversity of floral and ornamental arrangements used in the design of modern interiors of public spaces. The aim of the article is to grasp current trends of Green Urbanism regarding the diversity of floral and ornamental arrangements used in the design of modern interiors of public premises. Cross-cultural comparative methods have been used, partially using the hermeneutics of old-printed texts in accordance with the modern system of scientific knowledge. The historical antecedents of ornamental gardening, horticulture, forestry and vegetable growing, new trends in the ornamental plants cultivation, modern aspects of Green Urbanism are discussed. The need for the introduction of indoor plants in the residential and office premises interiors is argued in order to create a favorable atmosphere for work and leisure. -

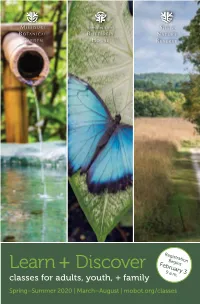

Learn + Discover February 3 9 A.M

ADULT CLASSES | DIY CRAFTS CLASSES | DIY ADULT Registration Begins Learn + Discover February 3 9 a.m. classes for adults, youth, + family Spring–Summer 2020 | March–August | mobot.org /classes Registration starts February 3 at 9 a.m.! Sign up online at mobot.org/classes. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE CRAFTS CLASSES | DIY ADULT Offered for a diversity of learners, from young explorers to budding enthusiasts Your love for plants to skilled gardeners, our courses have been expertly designed to educate, can change the world. inspire, and enrich. Most importantly, they are intended to strengthen the connections each of us has with the natural world and all its wonders. Whether you’re honing your gardening skills, flexing your Come grow with us! creativity, or embracing your inner ecologist, our classes equip you to literally transform landscapes and lives. And you thought you were just signing up for a fun class. SITE CODES How will you discover + share? Whether you visit 1 of our 3 St. Louis MBG: Missouri Botanical Garden area locations with family and friends, SNR: Shaw Nature Reserve enjoy membership in our organization, BH: Sophia M. Sachs Butterfly House take 2 of our classes, or experience a off-site: check class listing special event, you’re helping save at-risk species and protect habitats close to home and around the world. © 2020 Missouri Botanical Garden. On behalf of the Missouri Botanical Printed on 30% post-consumer recycled paper. Please recycle. Garden and our 1 shared planet… thank you. Designer: Emily Rogers Photography: Matilda Adams, Flannery Allison, Hayden Andrews, Amanda Attarian, Kimberly Bretz, Dan Brown, “To discover and share knowledge Kent Burgess, Cara Crocker, Karen Fletcher, Suzann Gille, Lisa DeLorenzo Hager, Elizabeth Harris, Ning He, Tom about plants and their environment Incrocci, Yihuang Lu, Jean McCormack, Cassidy Moody, in order to preserve and enrich life.” Kat Niehaus, Mary Lou Olson, Rebecca Pavelka, Margaret Schmidt, Sundos Schneider, Doug Threewitt, and courtesy —mission of the Missouri Botanical Garden of Garden staff. -

Botanical Gardens in the West Indies John Parker: the Botanic Garden of the University of Cambridge Holly H

A Publication of the Foundation for Landscape Studies A Journal of Place Volume ıı | Number ı | Fall 2006 Essay: The Botanical Garden 2 Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Introduction Fabio Gabari: The Botanical Garden of the University of Pisa Gerda van Uffelen: Hortus Botanicus Leiden Rosie Atkins: Chelsea Physic Garden Nina Antonetti: British Colonial Botanical Gardens in the West Indies John Parker: The Botanic Garden of the University of Cambridge Holly H. Shimizu: United States Botanic Garden Gregory Long: The New York Botanical Garden Mike Maunder: Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Profile 13 Kim Tripp Exhibition Review 14 Justin Spring: Dutch Watercolors: The Great Age of the Leiden Botanical Garden New York Botanical Garden Book Reviews 18 Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: The Naming of Names: The Search for Order in the World of Plants By Anna Pavord Melanie L. Simo: Henry Shaw’s Victorian Landscapes: The Missouri Botanical Garden and Tower Grove Park By Carol Grove Judith B. Tankard: Maybeck’s Landscapes By Dianne Harris Calendar 22 Contributors 23 Letter from the Editor The Botanical Garden he term ‘globaliza- botanical gardens were plant species was the prima- Because of the botanical Introduction tion’ today has established to facilitate the ry focus of botanical gardens garden’s importance to soci- The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries widespread cur- propagation and cultivation in former times, the loss of ety, the principal essay in he botanical garden is generally considered a rency. We use of new kinds of food crops species and habitats through this issue of Site/Lines treats Renaissance institution because of the establishment it to describe the and to act as holding opera- ecological destruction is a it as a historical institution in 1534 of gardens in Pisa and Padua specifically Tgrowth of multi-national tions for plants and seeds pressing concern in our as well as a landscape type dedicated to the study of plants. -

Greenwashed: Identity and Landscape at the California Missions’

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUPUIScholarWorks ‘GREENWASHED: IDENTITY AND LANDSCAPE AT THE CALIFORNIA MISSIONS’ Elizabeth KRYDER-REID Indiana University, Indianapolis (IUPUI), 410 Cavanaugh Hall, 425 University Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 56202, USA [email protected] Abstract: This paper explores the relationship of place and identity in the historical and contemporary contexts of the California mission landscapes, conceiving of identity as a category of both analysis and practice (Brubaker and Cooper 2000). The missions include twenty-one sites founded along the California coast and central valley in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The missions are all currently open to the public and regularly visited as heritage sites, while many also serve as active Catholic parish churches. This paper offers a reading of the mission landscapes over time and traces the materiality of identity narratives inscribed in them, particularly in ‘mission gardens’ planted during the late 19th and first half of the 20th century. These contested places are both celebrated as sites of California's origins and decried as spaces of oppression and even genocide for its indigenous peoples. Theorized as relational settings where identity is constituted through narrative and memory (Sommers 1994; Halbwachs 1992) and experienced as staged, performed heritage, the mission landscapes bind these contested identities into a coherent postcolonial experience of a shared past by creating a conceptual -

GARDENS and LANDSCAPES - Prof

GARDENS AND LANDSCAPES - Prof. Claudia M. Bucelli New York University - Villa La Pietra Florence Monday – Wednesday 9-12 Email: [email protected] Mobile: 347/1965439 Class lectures take place at New York University. Field trips take place from meeting points to pre-established sites and all visits will be guided, detailed information regarding the meeting points, timetables, means of transport, will be confirmed and communicated the week prior to the excursion. DESCRIPTION: Since the period of the Grand Tour Italy has been defined as the “the Garden of Europe” and up to present day it has still maintained in the contours of its own landscapes the anthropic activity of the past. Combined with its natural beauty which through the passing centuries has softened its contours, designing agricultural texture and street mapping while placing amongst the predominant urban and architectural landscapes a variety of gardens as a testimonial of a culture that since antiquity has associated nature to the design of places for intellectual, contemplative activities of man. Placed in the vicinity of eminent architectures which had both an aesthetic as well as a productive aim these gardens are an ideological translation of an earthy metaphysical vision of the world in addition to providing a formal and privileged model within the sector of technical experimentation. The garden after all also represents the place where the relationship between man and nature takes place, of which it is the image of the history of the gardens, as defined by Massimo Venturi Ferriolo as “aesthetics gardens within the aesthetic range of the landscape”, can be generally summarized as the history of the creation of environments emulating the Paradise, the Elysium, and the Myth in lay culture, the Eden for the Christian Jewish, and, even more, an environment suitable for competing and emulating extreme detailed research, offering wonder and a variety of repetition of gestures and the structural effect of the first one ,both paradigmatic and exemplary at the same time. -

Medieval Monastery Gardens in Iceland and Norway

religions Article Medieval Monastery Gardens in Iceland and Norway Per Arvid Åsen Natural History Museum and Botanical Garden, University of Agder, 4604 Kristiansand, Norway; [email protected] Abstract: Gardening was an important part of the daily duties within several of the religious orders in Europe during the Middle Ages. The rule of Saint Benedict specified that the monastery should, if possible, contain a garden within itself, and before and above all things, special care should be taken of the sick, so that they may be served in very deed, as Christ himself. The cultivation of medicinal and utility plants was important to meet the material needs of the monastic institutions, but no physical garden has yet been found and excavated in either Scandinavia or Iceland. The Cistercians were particularly well known for being pioneer gardeners, but other orders like the Benedictines and Augustinians also practised gardening. The monasteries and nunneries operating in Iceland during medieval times are assumed to have belonged to either the Augustinian or the Benedictine orders. In Norway, some of the orders were the Dominicans, Fransiscans, Premonstratensians and Knights Hospitallers. Based on botanical investigations at all the Icelandic and Norwegian monastery sites, it is concluded that many of the plants found may have a medieval past as medicinal and utility plants and, with all the evidence combined, they were most probably cultivated in monastery gardens. Keywords: medieval gardening; horticulture; monastery garden; herb; relict plants; medicinal plants Citation: Åsen, Per Arvid. 2021. Medieval Monastery Gardens in 1. Introduction Iceland and Norway. Religions 12: Monasticism originated in Egypt’s desert, and the earliest monastic gardens were 317. -

Western Americana

CATALOGUE TWO HUNDRED NINETY-NINE Western Americana WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue contains much in the way of new acquisitions in Western Americana, along with several items from our stock that have not been featured in recent catalogues. Printed, manuscript, cartographic, and visual materials are all represented. A theme of the catalogue is the exploration, settlement, and development of the trans-Mississippi West, and the time frame ranges from the 16th century to the early 20th. Highlights include copies of the second and third editions of The Book of Mormon; a certificate of admission to Stephen F. Austin’s Texas colony; a document signed by the Marquis de Lafayette giving James Madison power of attorney over his lands in the Louisiana Territory; an original drawing of Bent’s Fort; and a substantial run of the wonderfully illustrated San Francisco magazine, The Wasp, edited by Ambrose Bierce. Speaking of periodicals, we are pleased to offer the lengthiest run of the first California newspaper to appear on the market since the Streeter Sale, as well as a nearly complete run of The Dakota Friend, printed in the native language. There are also several important, early California broadsides documenting the political turmoil of the 1830s and the seizure of control by the United States in the late 1840s. From early imprints to original artwork, from the fur trade to modern construction projects, a wide variety of subjects are included. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues 291 The United States Navy; 292 96 American Manuscripts; 294 A Tribute to Wright Howes: Part I; 295 A Tribute to Wright Howes: Part II; 296 Rare Latin Americana; 297 Recent Acquisitions in Ameri- cana, as well as Bulletins 25 American Broadsides; 26 American Views; 27 Images of Native Americans; 28 The Civil War; 29 Photographica, and many more topical lists. -

Encounters with America's Premier Nursery and Botanic Garden

2004 Encounters with America’s Premier Nursery and Botanic Garden , and omas insects (including “musketoes” and the Jefferson,T then Secretary of State under Hessian fly), recording observations on George Washington, was embroiled in climate, the seasons and the appearance various political and personal matters. His of birds, and even boating and fishing in ideological vision for America, in conflict Lake George and Lake Champlain. with the governmental system espoused by eir journey did, nevertheless, in- Alexander Hamilton, was causing political corporate elements of a working vaca- relationships to crumble and his already tion, for Jefferson was seeking ways to strained friendship with John Adams advance the new nation through alterna- to deteriorate further. Consequently, tive domestic industries. He believed his Jefferson’s month-long “botanizing excur- most recent idea—the addition “to the sion” through New England with James products of the U. S. of three such articles Madison in June was the subject of much as oil, sugar, and upland rice”—would speculation that summer. Hamilton and lessen America’s reliance on foreign other political adversaries were con- trade, improve the lot of farmers, and vinced that this lengthy vacation of two ultimately result in the abolition of slav- Republican Virginians through Federalist ery itself. At that time a Quaker activist strongholds in the North had secret, ul- and philanthropist Dr. Benjamin Rush of terior motives. It would seem likely that, Philadelphia, himself an ardent opponent as -

The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections

Guide to the Geographic File ca 1800-present (Bulk 1850-1950) PR20 The New-York Historical Society 170 Central Park West New York, NY 10024 Descriptive Summary Title: Geographic File Dates: ca 1800-present (bulk 1850-1950) Abstract: The Geographic File includes prints, photographs, and newspaper clippings of street views and buildings in the five boroughs (Series III and IV), arranged by location or by type of structure. Series I and II contain foreign views and United States views outside of New York City. Quantity: 135 linear feet (160 boxes; 124 drawers of flat files) Call Phrase: PR 20 Note: This is a PDF version of a legacy finding aid that has not been updated recently and is provided “as is.” It is key-word searchable and can be used to identify and request materials through our online request system (AEON). PR 000 2 The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections PR 020 GEOGRAPHIC FILE Series I. Foreign Views Series II. American Views Series III. New York City Views (Manhattan) Series IV. New York City Views (Other Boroughs) Processed by Committee Current as of May 25, 2006 PR 020 3 Provenance Material is a combination of gifts and purchases. Individual dates or information can be found on the verso of most items. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers. Portions of the collection that have been photocopied or microfilmed will be brought to the researcher in that format; microfilm can be made available through Interlibrary Loan. Photocopying Photocopying will be undertaken by staff only, and is limited to twenty exposures of stable, unbound material per day.