Today However the Abundance of Material Has Made It the Most Extensive of All the Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Dahlia Myths.Pub

Cavanilles’ detailed illustrations established the dahlia in the botanical taxonomy In 1796, the third volume of “Icones” introduced two more dahlia species, named D. coccinea and D. rosea. They also were initially thought to be sunflowers and had been brought to Spain as part of the Alejandro Malaspina/Luis Neé expedition. More than 600 drawings brought the plant collection to light. Cavanilles, whose extensive correspondence included many of Europe’s leading botanists, began to develop a following far greater than his title of “sacerdote” (priest, in French Abbé) ever would have offered. The A. J. Cavanilles archives of the present‐day Royal Botanical Garden hold the botanist’s sizable oeu‐ vre, along with moren tha 1,300 letters, many dissertations, studies, and drawings. In time, Cavanilles achieved another goal: in 1801, he was finally appointed professor and director of the garden. Regrettably, he died in Madrid on May 10, 1804. The Cavanillesia, a tree from Central America, was later named for this famousMaterial Spanish scientist. ANDERS DAHL The lives of Dahl and his Spanish ‘godfather’ could not have been any more different. Born March 17,1751, in Varnhem town (Västergötland), this Swedish botanist struggled with health and financial hardship throughout his short life. While attending school in Skara, he and several teenage friends with scientific bent founded the “Swedish Topographic Society of Skara” and sought to catalogue the natural world of their community. With his preacher father’s support, the young Dahl enrolled on April 3, 1770, at Uppsala University in medicine, and he soon became one of Carl Linnaeus’ students. -

Green Spaces Brochure

Black Environment Network Ethnic Communities and Green Spaces Guidance for green space managers Green Space Location Type of space Theme Focus Use Improve Create 1 Abbeyfield Park Sheffield Urban park Multi-cultural festival in the park Park dept promoting use by ethnic communities / 2 Abney Park Cemetery London Local Nature Reserve Ecology, architecture and recreation Biodiversity awareness raising in mixed use space / 3 Al Hilal Manchester Community centre garden Improving the built environment Cultural and religious identity embodied in design / 4 Calthorpe Project London Multi-use green space Multi-functional inner city project Good design brings harmony among diverse users / 5 Cashel Forest Sterling Woodland (mixed) Commemorative forest of near-native ecology Refugee volunteers plant /tend commemorative trees / 6 Chelsea Physic Garden S. London Botanic garden Medicinal plants from around the world Pleasure visit/study facility with cultural links / 7 Chinese Hillside RBGE Edinburgh Botanic garden Simulated Chinese ecological landscape Living collection/ecological experiment / 8 Chumleigh Gardens S. London Multicultural gardens Park gardens recognising local ethnic presence Public park created garden reflecting different cultures / 9 Clovelly Centre Southampton Community centre garden Outdoor recreation space for older people Culturally sensitive garden design / 10 Concrete to Coriander Birmingham Community garden Expansion of park activities for food growing Safe access to land for Asian women / 11 Confused Spaces Birmingham Incidental -

Current Trends in Green Urbanism and Peculiarities of Multifunctional Complexes, Hotels and Offices Greening

Ukrainian Journal of Ecology Ukrainian Journal of Ecology, 2020, 10(1), 226-236, doi: 10.15421/2020_36 REVIEW ARTICLE UDK 364.25: 502.313: 504.75: 635.9: 711.417.2/61 Current trends in Green Urbanism and peculiarities of multifunctional complexes, hotels and offices greening I. S. Kosenko, V. M. Hrabovyi, O. A. Opalko, H. I. Muzyka, A. I. Opalko National Dendrological Park “Sofiyivka”, National Academy of Science of Ukraine Kyivska St. 12а, Uman, Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: 10.02.2020 Accepted 06.03.2020 The analysis of domestic and world publications on the evolution of ornamental garden plants use from the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and ancient Romans to the “dark times” of the middle Ages and the subsequent Renaissance was carried out. It was made in order to understand the current trends of Green Urbanism and in particular regarding the diversity of floral and ornamental arrangements used in the design of modern interiors of public spaces. The aim of the article is to grasp current trends of Green Urbanism regarding the diversity of floral and ornamental arrangements used in the design of modern interiors of public premises. Cross-cultural comparative methods have been used, partially using the hermeneutics of old-printed texts in accordance with the modern system of scientific knowledge. The historical antecedents of ornamental gardening, horticulture, forestry and vegetable growing, new trends in the ornamental plants cultivation, modern aspects of Green Urbanism are discussed. The need for the introduction of indoor plants in the residential and office premises interiors is argued in order to create a favorable atmosphere for work and leisure. -

An Investigation Into the Suitability of Paulownia As an Agroforestry Species for UK & NW European Farming Systems

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311558333 An investigation into the suitability of Paulownia as an agroforestry species for UK & NW European farming systems Thesis · May 2016 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.31955.78882 CITATION READS 1 2,475 1 author: Janus Bojesen Jensen Coventry University 1 PUBLICATION 1 CITATION SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: An Exploration of the Potential of Quantum-Based Agriculture for Sustainable Global Food Production View project Quantum Agriculture View project All content following this page was uploaded by Janus Bojesen Jensen on 10 December 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. An investigation into the suitability of Paulownia as an agroforestry species for UK & NW European farming systems Janus Bojesen Jensen, B.B.A. (Beirut) Submitted to the Department of Agriculture & Business Management, SRUC, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science SRUC, 2016 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Jo Smith for her invaluable support and guidance throughout this project. I would also like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Lou Ralph and all the teaching staff at SRUC for my experience and learning as a student at SRUC over the last three years. Lastly, I would like to express my thanks and appreciation to all the participants who were involved in this study and shared their time and knowledge with a particular acknowledgement to Dr. Ian Lane for all his contributions and for going the ‘extra country mile’ with me on two occasions. -

Learn + Discover February 3 9 A.M

ADULT CLASSES | DIY CRAFTS CLASSES | DIY ADULT Registration Begins Learn + Discover February 3 9 a.m. classes for adults, youth, + family Spring–Summer 2020 | March–August | mobot.org /classes Registration starts February 3 at 9 a.m.! Sign up online at mobot.org/classes. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE CRAFTS CLASSES | DIY ADULT Offered for a diversity of learners, from young explorers to budding enthusiasts Your love for plants to skilled gardeners, our courses have been expertly designed to educate, can change the world. inspire, and enrich. Most importantly, they are intended to strengthen the connections each of us has with the natural world and all its wonders. Whether you’re honing your gardening skills, flexing your Come grow with us! creativity, or embracing your inner ecologist, our classes equip you to literally transform landscapes and lives. And you thought you were just signing up for a fun class. SITE CODES How will you discover + share? Whether you visit 1 of our 3 St. Louis MBG: Missouri Botanical Garden area locations with family and friends, SNR: Shaw Nature Reserve enjoy membership in our organization, BH: Sophia M. Sachs Butterfly House take 2 of our classes, or experience a off-site: check class listing special event, you’re helping save at-risk species and protect habitats close to home and around the world. © 2020 Missouri Botanical Garden. On behalf of the Missouri Botanical Printed on 30% post-consumer recycled paper. Please recycle. Garden and our 1 shared planet… thank you. Designer: Emily Rogers Photography: Matilda Adams, Flannery Allison, Hayden Andrews, Amanda Attarian, Kimberly Bretz, Dan Brown, “To discover and share knowledge Kent Burgess, Cara Crocker, Karen Fletcher, Suzann Gille, Lisa DeLorenzo Hager, Elizabeth Harris, Ning He, Tom about plants and their environment Incrocci, Yihuang Lu, Jean McCormack, Cassidy Moody, in order to preserve and enrich life.” Kat Niehaus, Mary Lou Olson, Rebecca Pavelka, Margaret Schmidt, Sundos Schneider, Doug Threewitt, and courtesy —mission of the Missouri Botanical Garden of Garden staff. -

Workplace Growing

Briefing: Workplace growing The workplace growing concept Workplace growing encompasses a wide range of gardening activity on sites where people work. This could be private businesses with spare pieces of land available for growing, public spaces such as universities, hospitals, schools, or prisons or could belong to organisations like churches or village halls. These are places where volunteers, staff, patients, prisoners, parishioners, customers and students can come together and create a vibrant space to grow. Workplace growing is gardening activity supported by the workplace which allows a piece of land on their site to be used to for growing. In an RHS survey 73% of respondents said they considered gardening to be a good way of unwinding from the pressures of work and over half said if they had access to a workplace garden they would use it. Workplace growing often involves the staff who work on the site but then the local community is invited to use the land as well and actively participate in decisions about site design, what will be grown, when people will be on site and how they will all work together effectively. Workplace growing spaces are experiencing a higher profile as the demand for community growing spaces has increased. This is particularly relevant in areas where few open spaces are available to people and where those people want to create a garden, orchard or wildlife area. People have started to look beyond their own gardens, allotments, parks or other open spaces to find additional alternative growing sites. Workplace gardens are starting to look at new ways of using land more effectively in the spaces they work in. -

Botanical Gardens in the West Indies John Parker: the Botanic Garden of the University of Cambridge Holly H

A Publication of the Foundation for Landscape Studies A Journal of Place Volume ıı | Number ı | Fall 2006 Essay: The Botanical Garden 2 Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Introduction Fabio Gabari: The Botanical Garden of the University of Pisa Gerda van Uffelen: Hortus Botanicus Leiden Rosie Atkins: Chelsea Physic Garden Nina Antonetti: British Colonial Botanical Gardens in the West Indies John Parker: The Botanic Garden of the University of Cambridge Holly H. Shimizu: United States Botanic Garden Gregory Long: The New York Botanical Garden Mike Maunder: Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Profile 13 Kim Tripp Exhibition Review 14 Justin Spring: Dutch Watercolors: The Great Age of the Leiden Botanical Garden New York Botanical Garden Book Reviews 18 Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: The Naming of Names: The Search for Order in the World of Plants By Anna Pavord Melanie L. Simo: Henry Shaw’s Victorian Landscapes: The Missouri Botanical Garden and Tower Grove Park By Carol Grove Judith B. Tankard: Maybeck’s Landscapes By Dianne Harris Calendar 22 Contributors 23 Letter from the Editor The Botanical Garden he term ‘globaliza- botanical gardens were plant species was the prima- Because of the botanical Introduction tion’ today has established to facilitate the ry focus of botanical gardens garden’s importance to soci- The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries widespread cur- propagation and cultivation in former times, the loss of ety, the principal essay in he botanical garden is generally considered a rency. We use of new kinds of food crops species and habitats through this issue of Site/Lines treats Renaissance institution because of the establishment it to describe the and to act as holding opera- ecological destruction is a it as a historical institution in 1534 of gardens in Pisa and Padua specifically Tgrowth of multi-national tions for plants and seeds pressing concern in our as well as a landscape type dedicated to the study of plants. -

Greenwashed: Identity and Landscape at the California Missions’

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUPUIScholarWorks ‘GREENWASHED: IDENTITY AND LANDSCAPE AT THE CALIFORNIA MISSIONS’ Elizabeth KRYDER-REID Indiana University, Indianapolis (IUPUI), 410 Cavanaugh Hall, 425 University Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 56202, USA [email protected] Abstract: This paper explores the relationship of place and identity in the historical and contemporary contexts of the California mission landscapes, conceiving of identity as a category of both analysis and practice (Brubaker and Cooper 2000). The missions include twenty-one sites founded along the California coast and central valley in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The missions are all currently open to the public and regularly visited as heritage sites, while many also serve as active Catholic parish churches. This paper offers a reading of the mission landscapes over time and traces the materiality of identity narratives inscribed in them, particularly in ‘mission gardens’ planted during the late 19th and first half of the 20th century. These contested places are both celebrated as sites of California's origins and decried as spaces of oppression and even genocide for its indigenous peoples. Theorized as relational settings where identity is constituted through narrative and memory (Sommers 1994; Halbwachs 1992) and experienced as staged, performed heritage, the mission landscapes bind these contested identities into a coherent postcolonial experience of a shared past by creating a conceptual -

GARDENS and LANDSCAPES - Prof

GARDENS AND LANDSCAPES - Prof. Claudia M. Bucelli New York University - Villa La Pietra Florence Monday – Wednesday 9-12 Email: [email protected] Mobile: 347/1965439 Class lectures take place at New York University. Field trips take place from meeting points to pre-established sites and all visits will be guided, detailed information regarding the meeting points, timetables, means of transport, will be confirmed and communicated the week prior to the excursion. DESCRIPTION: Since the period of the Grand Tour Italy has been defined as the “the Garden of Europe” and up to present day it has still maintained in the contours of its own landscapes the anthropic activity of the past. Combined with its natural beauty which through the passing centuries has softened its contours, designing agricultural texture and street mapping while placing amongst the predominant urban and architectural landscapes a variety of gardens as a testimonial of a culture that since antiquity has associated nature to the design of places for intellectual, contemplative activities of man. Placed in the vicinity of eminent architectures which had both an aesthetic as well as a productive aim these gardens are an ideological translation of an earthy metaphysical vision of the world in addition to providing a formal and privileged model within the sector of technical experimentation. The garden after all also represents the place where the relationship between man and nature takes place, of which it is the image of the history of the gardens, as defined by Massimo Venturi Ferriolo as “aesthetics gardens within the aesthetic range of the landscape”, can be generally summarized as the history of the creation of environments emulating the Paradise, the Elysium, and the Myth in lay culture, the Eden for the Christian Jewish, and, even more, an environment suitable for competing and emulating extreme detailed research, offering wonder and a variety of repetition of gestures and the structural effect of the first one ,both paradigmatic and exemplary at the same time. -

The Collation and Collection of Heirloom Fruit and Vegetable Cultivars

International Specialised Skills Institute Inc THE COLLATION AND COLLECTION OF HEIRLOOM FRUIT AND VEGETABLE CULTIVARS Nicholas David Gowans The Pratt Foundation/ISS Institute Overseas Fellowship Fellowship supported by The Pratt Foundation .1 1 A 2 B ISS Institute Inc. 2009 © International Specialised Skills Institute ISS Institute Suite 101 685 Burke Road Camberwell Vic AUSTRALIA 3124 Telephone 03 9882 0055 Facsimile 03 9882 9866 Email [email protected] Web www.issinstitute.org.au Published by International Specialised Skills Institute, Melbourne. ISS Institute 101/685 Burke Road Camberwell 3124 AUSTRALIA Also extract published on www.issinstitute.org.au © Copyright ISS Institute 2009 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Whilst this report has been accepted by ISS Institute, ISS Institute cannot provide expert peer review of the report, and except as may be required by law no responsibility can be accepted by ISS Institute for the content of the report, or omissions, typographical, print or photographic errors, or inaccuracies that may occur after publication or otherwise. ISS Institute do not accept responsibility for the consequences of any action taken or omitted to be taken by any person as a consequence of anything contained in, or omitted from, this report. Executive Summary The aim of this Fellowship was to obtain first hand practical experience of heritage fruit and vegetables, and their relevance in Australian horticultural production systems. The knowledge and skills obtained overseas can be shared with others who have an interest in the practical application of these processes and the subsequent lessons to be entrenched into future horticultural programs and research and development. -

Creating a Modern Apothecary Garden

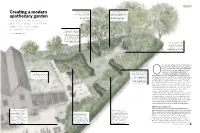

DESIGN A central area is planted with a A south-facing berry patch can be Creating a modern simple clover rich lawn mix. decorative and delightful as well Cover adds nitrogen to the lawn as packing a punch with vitamins so keeps it healthy in the for the table. A mulberry tree is a apothecary garden summer and, when in flower, is permaculture favourite, needing also forage for bees. little attention and providing What we grow can be as good for us as delicious superfood berries. gardening itself. Designer Marian Boswall suggests ways to turn your garden into a pantry of healing herbs A simple Hügelkultur mound uses woody debris and plant waste piled up and covered with a layer WORDS MARIAN BOSWALL of soil to plant directly into. The nutrients are released quickly in the first year when demanding plants such as pumpkins and potatoes will thrive, and then as the mound sinks crops such as beans and peas take over. Rhubarb is happy in a shadier spot under the large shelter trees, while herbs creep between the stepping stones leading to the herb-drying room at the end of the garden, which also doubles as a writing room and yoga studio. ur health and energy is firmly entwined with the land around us and what grows on it, including the bits we eat. We know that a little gardening is good for us, so why not combine this with Edible hedges divide the different what we grow in a health-giving garden? A green roof adds an additional areas of the garden and provide layer of green to a garden and shelter and a backdrop for each From the beautifully laid out Plan of Saint here it is planted with flowers border. -

Medieval Monastery Gardens in Iceland and Norway

religions Article Medieval Monastery Gardens in Iceland and Norway Per Arvid Åsen Natural History Museum and Botanical Garden, University of Agder, 4604 Kristiansand, Norway; [email protected] Abstract: Gardening was an important part of the daily duties within several of the religious orders in Europe during the Middle Ages. The rule of Saint Benedict specified that the monastery should, if possible, contain a garden within itself, and before and above all things, special care should be taken of the sick, so that they may be served in very deed, as Christ himself. The cultivation of medicinal and utility plants was important to meet the material needs of the monastic institutions, but no physical garden has yet been found and excavated in either Scandinavia or Iceland. The Cistercians were particularly well known for being pioneer gardeners, but other orders like the Benedictines and Augustinians also practised gardening. The monasteries and nunneries operating in Iceland during medieval times are assumed to have belonged to either the Augustinian or the Benedictine orders. In Norway, some of the orders were the Dominicans, Fransiscans, Premonstratensians and Knights Hospitallers. Based on botanical investigations at all the Icelandic and Norwegian monastery sites, it is concluded that many of the plants found may have a medieval past as medicinal and utility plants and, with all the evidence combined, they were most probably cultivated in monastery gardens. Keywords: medieval gardening; horticulture; monastery garden; herb; relict plants; medicinal plants Citation: Åsen, Per Arvid. 2021. Medieval Monastery Gardens in 1. Introduction Iceland and Norway. Religions 12: Monasticism originated in Egypt’s desert, and the earliest monastic gardens were 317.