Explorations in Sights and Sounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda Semanal FILBA

Ya no (Dir. María Angélica Gil). 20 h proyecto En el camino de los perros AGENDA Cortometraje de ficción inspirado en PRESENTACIÓN: Libro El corazón y a la movida de los slam de poesía el clásico poema de Idea Vilariño. disuelto de la selva, de Teresa Amy. oral, proponen la generación de ABRIL, 26 AL 29 Idea (Dir. Mario Jacob). Documental Editorial Lisboa. climas sonoros hipnóticos y una testimonial sobre Idea Vilariño, Uno de los secretos mejor propuesta escénica andrógina. realizado en base a entrevistas guardados de la poesía uruguaya. realizadas con la poeta por los Reconocida por Marosa Di Giorgio, POÉTICAS investigadores Rosario Peyrou y Roberto Appratto y Alfredo Fressia ACTIVIDADES ESPECIALES Pablo Rocca. como una voz polifónica y personal, MONTEVIDEANAS fue también traductora de poetas EN SALA DOMINGO FAUSTINO 18 h checos y eslavos. Editorial Lisboa SARMIENTO ZURCIDORA: Recital de la presenta en el stand Montevideo de JUEVES 26 cantautora Papina de Palma. la FIL 2018 el poemario póstumo de 17 a 18:30 h APERTURA Integrante del grupo Coralinas, Teresa Amy (1950-2017), El corazón CONFERENCIA: Marosa di Giorgio publicó en 2016 su primer álbum disuelto de la selva. Participan Isabel e Idea Vilariño: Dos poéticas en solista Instantes decisivos (Bizarro de la Fuente y Melba Guariglia. pugna. 18 h Records). El disco fue grabado entre Revisión sobre ambas poetas iNAUGURACIÓN DE LA 44ª FERIA Montevideo y Buenos Aires con 21 h montevideanas, a través de material INTERNACIONAL DEL producción artística de Juanito LECTURA: Cinco poetas. Cinco fotográfico de archivo. LIBRO DE BUENOS AIRES El Cantor. escrituras diferentes. -

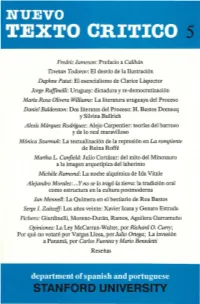

Texto Critico

NUEVO TEXTO CRITICO Fredric Jameson: Prefacio a Calibán Tzvetan Todorov: El desvío de la Ilustración Daphne Patai: El esencialismo de Clarice Lispector Jorge Ruffinelli: Uruguay: dictadura y re-democratización María Rosa Olivera Williams: La literatura uruguaya del Proceso Daniel Balderston: Dos literatos del Proceso: H. Bustos Domecq y Silvina Bullrich Alexis Márquez Rodríguez: Alejo Carpentier: teorías del barroco y de lo real maravilloso Mónica Szurmuk: La textualización de la represión en La rompiente de Reina Roffé Martha L. Canfield: Julio Cortázar: del mito del Minotauro a la imagen arquetípica del laberinto Michele Ramond: La noche alquímica de Ida Vitale Alejandro Morales: ... Y no se lo tragó la tierra: la tradición oral como estructura en la cultura postmoderna Jan Mennell: La Quimera en el bestiario de Roa Bastos Serge l. Zaitzeff: Los años veinte: Xavier Icaza y Genaro Estrada Fichero: Giardinelli, Moreno-Durán, Ramos, Aguilera Garramuño Opiniones: La Ley McCarran-Walter, por Richard O. Curry; Por qué no votaré por Vargas Llosa, por Julio Ortega; La invasión a Panamá, por Carlos Fuentes y Mario Benedetti Reseñas NUEVO TEXTO CRITICO AñoiU Primer semestre de 1990 No. S Fredric Jameson Prefacio a Calibán. ............................................................................................. 3 Tzvetan T odorov El desvío de la Ilustración .................................................................................. 9 Daphne Patai El esencialismo de Clarice Lispector ............................................................. -

Contemporary Voices Teacher Guide

Teacher Guide for High School for use with the educational DVD Contemporary Voices along the Lewis & Clark Trail First Edition The Regional Learning Project collaborates with tribal educators to produce top quality, primary resource materials about Native Americans, Montana, and regional history. Bob Boyer, Kim Lugthart, Elizabeth Sperry, Sally Thompson © 2008 Regional Learning Project, The University of Montana, Center for Continuing Education Regional Learning Project at the University of Montana–Missoula grants teachers permission to photocopy the activity pages from this book for classroom use. No other part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For more information regarding permission, write to Regional Learning Project, UM Continuing Education, Missoula, MT 59812. Acknowledgements Regional Learning Project extends grateful acknowledgement to the tribal representatives contributing to this project. The following is a list of those appearing in the DVD, from interviews conducted by Sally Thompson, Ph.D. Lewis Malatare (Yakama) Lee Bourgeau (Nez Perce) Allen Pinkham (Nez Perce) Julie Cajune (Salish) Pat Courtney Gold (Wasco) Maria Pascua (Makah) Armand Minthorn (Cayuse/Nez Perce) Cecelia Bearchum (Walla Walla/Yakama) Vernon Finley (Kootenai) Otis Halfmoon (Nez Perce) Louis Adams (Salish) Kathleen Gordon (Cayuse/Walla Walla) Felix -

Charles Eastman, Standing Bear, and Zitkala Sa

Dakota/Lakota Progressive Writers: Charles Eastman, Standing Bear, and Zitkala Sa Gretchen Eick Friends University a cold bare pole I seemed to be, planted in a strange earth1 This paper focuses on three Dakota/Lakota progressive writers: Charles Alexander Eastman (Ohiyesa) of the Santee/Dakota; Luther Standing Bear (Ota Kte) of the Brulé; and Gertrude Simmons Bonnin (Zitkala Sa) of the Yankton. All three were widely read and popular “Indian writers,” who wrote about their traumatic childhoods, about being caught between two ways of living and perceiving, and about being coerced to leave the familiar for immersion in the ways of the whites. Eastman wrote dozens of magazine articles and eleven books, two of them auto- biographies, Indian Boyhood (1902) and From the Deep Woods to Civilization (1916).2 Standing Bear wrote four books, two of them autobiographies, My People, the Sioux (1928) and My Indian Boyhood (1931).3 Zitkala Sa wrote more than a dozen articles, several auto-biographical, and nine books, one autobiographical, American Indian Stories (1921), and the others Dakota stories, such as Old Indian Legends (1901). She also co- wrote an opera The Sun Dance. 4 1 Zitkala Sa, “An Indian Teacher Among the Indians,” American Indian Stories, Legends, and Other Writings, Cathy N. Davidson and Ada Norris, eds., ( New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 112. 2The other titles are Red Hunters and the Animal People (1904), Old Indian Days (1907), Wigwam Evenings: Sioux Folk Tales Retold (1909), Smoky Day’s Wigwam Evenings: Indian Stories Retold (1910), The Soul of an Indian: An Interpretation (1911), Indian Child Life (1913), The Indian Today: The Past and Future of the First Americans (1915), Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains (1918), Indian Scout Talks: A Guide for Boy Scouts and Campfire Girls (1914), and his two autobiographies, Indian Boyhood (1902) and From the Deep Woods to Civilization (1916). -

Madrid, 21 De Diciembre De 2018 Circular 182/18 a Los Señores

Madrid, 21 de diciembre de 2018 Circular 182/18 A los señores secretarios de las Academias de la Lengua Española Francisco Javier Pérez Secretario general Luto en la Academia Salvadoreña de la Lengua por el fallecimiento, el miércoles 28 de noviembre de la académica Ana María Nafría (1947-2018). Ana María Nafría Ramos tomó posesión como académica de número en marzo de 2011 con el discurso titulado El estudio formal de la gramática y la adquisición del lenguaje. La profesora Nafría fue catedrática de tiempo completo en la Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas (UCA), donde impartió diversas materias de lingüística: Lingüística General, Lingüística de la Lengua Española, Gramática Superior de la Lengua Española, Historia de la Lengua Española, Técnicas de Redacción, Estilística, etc. Fue coordinadora del profesorado y de la licenciatura en Letras de la UCA. También fue vicerrectora adjunta de Administración Académica de dicha universidad. Entre sus publicaciones se destacan Titekitit. Esbozos de la gramática del nahuat-pipil de El Salvador (UCA, 1980), Lengua española. Elementos esenciales (UCA, 1999), para estudiantes de primer año de universidad; y, como coautora, Análisis de la enseñanza del lenguaje y la literatura en Tercer Ciclo y Bachillerato en los centros de enseñanza estatales de El Salvador (1994); Idioma nacional (UCA Editores, 1989), y los textos Lenguaje y literatura para 7.º, 8.º y 9.º grados, según los programas del Ministerio de Educación. Descanse en paz nuestra colega salvadoreña. Madrid, 21 de diciembre de 2018 Circular 183/18 A los señores secretarios de las Academias de la Lengua Española Francisco Javier Pérez Secretario general La Academia Peruana de la Lengua organizó el curso gratuito «Fonética y sus aplicaciones en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje de segundas lenguas», a cargo del profesor de la Universidad Mayor de San Marcos Rolando Rocha Martínez. -

ANGELA A. GONZALES Curriculum Vitae

ANGELA A. GONZALES Curriculum Vitae Arizona State University Email: [email protected] School of Social Transformation Office: 480.727.3671 777 Novus, Suite 310AA Mobile: 607.279.5492 Tempe, AZ 85287-4308 PERSONAL: Enrolled Hopi Tribal Citizen EDUCATION 2002 Ph.D., Sociology, Harvard University 1997 M.A., Sociology, Harvard University 1994 Ed.M., Education Policy and Management, Harvard Graduate School of Education 1990 B.A., Sociology, University of California-Riverside EMPLOYMENT Academic Appointments 2016 – present Associate Professor, Justice & Social Inquiry, School of Social Transformation, Arizona State University 2010 – 2016 Associate Professor, Department of Development Sociology, Cornell University 2009 – 2010 Ford Postdoctoral Diversity Fellow, National Academies. Fellowship site: Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC 2006 – 2007 Postdoctoral Fellow, National Institute on Aging (NIA) Native Investigator Development Program, Resource Center for Minority Aging Research/Native Elder Research Center, University of Colorado Health Science University 2002 – 2010 Assistant Professor, Department of Development Sociology, Cornell University 1999 – 2001 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Rural Sociology, Cornell University 1997 – 1999 Assistant Professor, American Indian Studies, San Francisco State University Administrative Appointments 2019 – present Associate Director, School of Social Transformation, Arizona State University 2019 – 2020 Director of Graduate Studies, Justice and Social Inquiry, School of Social Transformation, Arizona State University 2018 – 2019 Faculty Head, Justice & Social Inquiry, Arizona State University 2015 – 2016 Director of Undergraduate Studies, Department of Development Sociology, Cornell University 1997 – 1998 Chair, American Indian Studies, San Francisco State University 1994-1996 Director, Hopi Grants and Scholarship and Adult Vocational Training Program, Hopi Tribe, Kykotsmovi, AZ PUBLICATIONS Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles Kertész, J. -

Gendered Ideals in the Autobiographies of Charles Eastman and Luther Standing Bear

Compromising and Accommodating Dominant Gendered Ideologies: The Effectiveness of Using Nineteenth-century Indian Boarding school Autobiographies as Tools of Protest Sineke Elzinga S1012091 M North American Studies 24 June 2019 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Hans Bak Second Reader: Dr. Mathilde Roza NORTH AMERICAN STUDIES Teacher who will receive this document: Prof. Dr. Hans Bak and Dr. Mathilde Roza Title of document: Compromising and Accommodating Dominant Gendered Ideologies: The Effectiveness of Using Nineteenth-century Indian Boarding school Autobiographies as Tools of Protest Name of course: Master Thesis Date of submission: 25 June 2019 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Sineke Elzinga Student number: S1012091 Abstract Gendered ideals dominant in nineteenth-century America have been significantly different from gendered ideals in Native American communities. In using their Indian boarding schools autobiographies as tools of protest, these Native writers had to compromise and accommodate these gendered ideals dominant in American society. This thesis analyzes how Zitkála-Šá, Luther Standing Bear and Charles Eastman have used the gendered ideals concerning the public and domestic sphere, emotion and reason in writing, and ideas about individuality and analyzes how this has affected the effectiveness of using their autobiographies as tools of protest for their people. Keywords Indian boarding school autobiographies, -

The Santee Sioux Claims Case / Raymond Wilson

Forty Years to Judgment Raymond Wilson THE SANTEE, or Eastern Sioux (Dakota), as they first By 1858 the Santee lived on the southern side of the became known to their relati\'es to the West, consist of Minnesota on a reservation 150 miles long and only 10 four major subdi\'isions: Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Sis miles wide. The Wahpeton and Sisseton bands, served seton, and Wahpeton. They were in present-day .Minne by the Upper (Y'ellow Medicine) Agency, lived in an area sota as early as the 17th centur)- but were gi-aduall)' from Traverse and Big Stone lakes to the mouth of the forced by their Ojibway enemies from Mille Lacs and Yellow Medicine River; the Mdewakanton and Wahpe- other lakes to lands south and west along the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers. Then the)' became victims of HOMELANDS of the Santee Sioux after 1862 white eucroachinent. Much has been written about these Indians, but no one has delved very deeply into a SOUTH % il SI. Paul Santee claims case that stretched well into the 20th cen [Upper '''i/,^ tur)'. This involved the restoration of annuities tor the ,^ . i^ ^ T, . ' Sioux %, DAKOTA j Agency* ''^,^^ Hlvei Lower Santee — the Mdewakanton especially, and the Crow m Wahpekute — the subtribes held primarily responsible ^ Creek Lower Sioux Mankato Reservation Agenc- y• • for the Dakota War, or Sioux Uprising, of 1862 in Min Ftandfeau MINNESOTA nesota. (The complicated Sisseton-W'ahpetou claims case, settled in 1907, has received more attention.)' By 1862 the Santee were filled with resentment and frustration. Two hundred )'ears of contact with whites IOWA ^""^-"/?«,.. -

The Assimilation of Captives on the American Frontier in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1977 The Assimilation of Captives on the American Frontier in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Joseph Norman Heard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Heard, Joseph Norman, "The Assimilation of Captives on the American Frontier in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries." (1977). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3157. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3157 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Discussion Guide for “Living in Two Worlds” by Charles Eastman

Living in Two worLds — wisdom TaLes discussion guide Summary • From buffalo hunter to medical doctor and author, discover the fascinating life of Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa) • Award-winning editor Michael Oren Fitzgerald expertly selects passages from renowned author Charles Eastman’s (Ohiyesa) writings to tell the American Indian experience of “living in two worlds” over the last four centuries • Fully illustrated with more than 275 color and b&w photos, paintings, vignettes, historical timelines, and maps • With a Foreword by Chief James Trosper, Shoshone Sun Dance chief and features nine interviews with contemporary American Indian leaders • Contains extensive discussion questions and helpful lists of free supplementary study materials About the Book From buffalo hunter to medical doctor and author, this is the compelling story of Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa) who embraced a life of the traditional cultural ideals of his nomadic ancestors while living in the modern industrialized world. Filled with first-hand accounts, personal stories, interviews, timelines, maps, and over 275 stunning vintage photographs and paintings, this beautifully illustrated award-winning book presents a vivid account of the American Indian experience. Winner of the ForeWord Book of the Year Gold Medal in the “Social Science”category; About the Author Winner of the Benjamin Franklin Gold Award for “Multicultural” Ohiyesa, also known as Charles Alexander Eastman, was the first 3 Gold Midwest Independent Publishers Association Book great American Indian author, publishing 11 books from 1902 Awards for: “Culture,”“Interior Layout,”and “Color Cover” until 1918. Ohiyesa was raised by his grandparents in the traditional Winner in the “Multicultural Non-Fiction”category of manner until the age of 15 when he entered the “white man’s world.” The USA “Best Books 2011”Awards He graduated from Dartmouth College and Boston College with a medical degree,and he was the first doctor to treat the survivors of the Wounded Knee massacre. -

DD Native Americans.Indd

Table of Contents Publisher’s Note . vii Editor’s Introduction . ix Contributors . xiii Early Encounters and Conflicts Iroquois Thanksgiving Address . .3 Christopher Columbus: Letter to Raphael Sanxis on the Discovery of America . 11 John Smith: The Generall Historie of Virginia . 23 Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson . 33 Appeal to Choctaws and Chickasaws . 42 Memorial to Congress . 47 Cherokee Nation v. Georgia . 51 Worcester v. Georgia . 58 Western Wars and Aftermaths Battle of Sand Creek: Editorials and Congressional Testimony. 65 Treaty of Fort Laramie . 85 Status Report on the Condition of the Navajos . 93 Accounts of the Battle of Little Bighorn . 99 Address of the Lake Mohonk Conference on Indian Affairs . 104 Dawes Severalty Act . 109 Trouble on the Paiute Reservation . 119 Wounded Knee Massacre: Statements and Eyewitness Accounts . 123 New Lives and Circumstances Charles Eastman: Indian Boyhood . 135 The Surrender of Geronimo . 143 The Ghost Dance Religion – Wovoka’s “Messiah Letter” and Z.A. Parker’s “The Ghost Dance Among the Lakota” . 150 Edward S. Curtis: Introduction to The North American Indian . 157 A New Deal for American Indians . 163 Letter Recommending Navajo Enlistment . 167 v DDDD NNativeative AAmericans.inddmericans.indd v 111/5/20171/5/2017 111:20:301:20:30 PPMM Indian Civil Rights Act . 171 Indians of All Tribes Occupation of Alcatraz: Proclamation . 177 “Trail of Broken Treaties” Twenty-Point Position Paper . 182 American Indian Movement—National Operational Goal . 188 President Gerald Ford’s Statement on Signing the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 . 193 American Indian Religious Freedom Act . -

Semanario JAQUE

Semanario JAQUE A partir del triunfo del NO al proyecto militar de la dictadura, plebiscitado en 1980, se abrió un espacio público que resulta central para entender la historia de aquellos años: los semanarios. Un hito en la historia del periodismo nacional. El proceso militar tenía una gran capacidad de presionar de muchas maneras a los grandes medios de la prensa escrita, radial o televisiva, entre ellas económicamente ya que el equilibrio de dichas empresas contaba imprescindiblemente con la publicidad estatal. Recuérdese que Uruguay es un pequeño país con un Estado grande. Surgió así a través de pequeñas empresas -cuyas publicaciones no tenían publicidad estatal- una válvula de escape en el oprimido ambiente de la dictadura: los semanarios. Entre los semanarios JAQUE tuvo un enorme impacto por su fuerte impronta de periodismo cultural y de investigación que desarrollaba al servicio del arco democrático, lo que supuso un gran tiraje semanal. Había semanarios para traducir la sensibilidad de las tres corrientes de opinión del país, pero todos mostraban un pluralismo que fue imprescindible para derrotar al autoritarismo. JAQUE se destacó en este campo, pero no debe olvidarse, por ejemplo, que Opinar tenía de columnistas permanentes a ciudadanos que, dada su conocida filiación política, luego tuvieron los más altos destinos públicos desde las otras vertientes de opinión. JAQUE articuló en ese tiempo por lo menos tres operaciones intelectuales y políticas trascendentes. 1.- Arrinconar al régimen autoritario. Por un lado, fue centralmente funcional a la estrategia del arco opositor particularmente entre el casi año que transcurre entre el fracaso de las negociaciones llamadas del Parque Hotel (1983) y las negociaciones del Club Naval (1984).