Cross-Sectional Imaging in the Evaluation of Osteogenic Sarcoma: MRI and CT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Practice Guideline for Limb Salvage Or Early Amputation

Limb Salvage or Early Amputation Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline Adopted by: The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Board of Directors December 6, 2019 Endorsed by: Please cite this guideline as: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Limb Salvage or Early Amputation Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/quality-and-practice-resources/dod/ lsa-cpg-final-draft-12-10-19.pdf Published December 6, 2019 View background material via the LSA CPG eAppendix Disclaimer This clinical practice guideline was developed by a physician volunteer clinical practice guideline development group based on a formal systematic review of the available scientific and clinical information and accepted approaches to treatment and/or diagnosis. This clinical practice guideline is not intended to be a fixed protocol, as some patients may require more or less treatment or different means of diagnosis. Clinical patients may not necessarily be the same as those found in a clinical trial. Patient care and treatment should always be based on a clinician’s independent medical judgment, given the individual patient’s specific clinical circumstances. Disclosure Requirement In accordance with AAOS policy, all individuals whose names appear as authors or contributors to this clinical practice guideline filed a disclosure statement as part of the submission process. All panel members provided full disclosure of potential conflicts of interest prior to voting on the recommendations contained within this clinical practice guideline. Funding Source This clinical practice guideline was funded exclusively through a research grant provided by the United States Department of Defense with no funding from outside commercial sources to support the development of this document. -

En Bloc Resection of Extra-Peritoneal Soft Tissue Neoplasms Incorporating a Type III Internal Hemipelvectomy: a Novel Approach Sanjay S Reddy1* and Norman D Bloom2

Reddy and Bloom World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2012, 10:222 http://www.wjso.com/content/10/1/222 WORLD JOURNAL OF SURGICAL ONCOLOGY REVIEW Open Access En bloc resection of extra-peritoneal soft tissue neoplasms incorporating a type III internal hemipelvectomy: a novel approach Sanjay S Reddy1* and Norman D Bloom2 Abstract Background: A type III hemipelvectomy has been utilized for the resection of tumors arising from the superior or inferior pubic rami. Methods: In eight patients, we incorporated a type III internal hemipelvectomy to achieve an en bloc R0 resection for tumors extending through the obturator foramen or into the ischiorectal fossa. The pelvic ring was reconstructed utilizing marlex mesh. This allowed for pelvic stability and abdominal wall reconstruction with obliteration of the obturator space to prevent herniations. Results: All eight patients had an R0 resection with an overall survival of 88% and with average follow up of 9.5 years. Functional evaluation utilizing the Enneking classification system, which evaluates motion, pain, stability and strength of the affected extremity, revealed a 62% excellent result and a 37% good result. No significant complications were associated with the operative procedure. Marlex mesh reconstruction provided pelvic stability and eliminated all hernial defects. Conclusion: The superior and inferior pubic rami provide a barrier to a resection for tumors that arise in the extra-peritoneal pelvis extending through the obturator foramen or ischiorectal fossa. Incorporating a type III internal -

Use of Anterolateral Thigh Flap for Reconstruction of Traumatic Bilateral Hemipelvectomy After Major Pelvic Trauma

Al‑wageeh et al. surg case rep (2020) 6:247 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792‑020‑01009‑2 CASE REPORT Open Access Use of anterolateral thigh fap for reconstruction of traumatic bilateral hemipelvectomy after major pelvic trauma: a case report Saleh Al‑wageeh1 , Faisal Ahmed2* , Khalil Al‑naggar3 , Mohammad Reza Askarpour4 and Ebrahim Al‑shami5 Abstract Background: Major pelvic trauma (MPT) with traumatic hemipelvectomy (THP) is rare, but it is a catastrophic health problem caused by high‑energy injury leading to separation of the lower extremity from the axial skeleton, which is associated with a high incidence of intra‑abdominal and multi‑systemic injuries. THP is generally performed as a lifesaving protocol to return the patient to an active life. Case report: A 12‑year male patient exposed to major pelvic trauma with bilateral THP survived the trauma and mul‑ tiple lifesaving operations. The anterolateral thigh fap is the method used for wound reconstruction. The follow‑up was ended with colostomy and cystostomy with wheelchair mobilization. To the best of our knowledge, there have been a few bilateral THP reports, and our case is the second one to be successfully treated with an anterolateral thigh fap. Conclusion: MPT with THP is the primary cause of death among trauma patients. Life‑threatening hemorrhage is the usual cause of death, which is a strong indication for THP to save life. Keywords: Amputation, Hemipelvectomy, Myocutaneous fap, Reconstruction, Trauma Introduction A few victims survive these injuries, and the actual Major pelvic trauma (MPT) associated with traumatic incidence is unknown, but it is usually underestimated hemipelvectomy (THP) was described frst by Turnbull in [3]. -

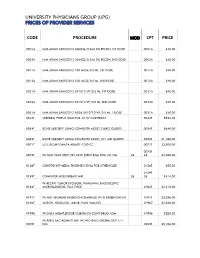

Code Procedure Cpt Price University Physicians Group

UNIVERSITY PHYSICIANS GROUP (UPG) PRICES OF PROVIDER SERVICES CODE PROCEDURE MOD CPT PRICE 0001A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 30MCG/0.3ML DIL RECON 1ST DOSE 0001A $40.00 0002A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 30MCG/0.3ML DIL RECON 2ND DOSE 0002A $40.00 0011A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 100 MCG/0.5 ML 1ST DOSE 0011A $40.00 0012A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 100 MCG/0.5 ML 2ND DOSE 0012A $40.00 0021A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 5X1010 VP/0.5 ML 1ST DOSE 0021A $40.00 0022A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 5X1010 VP/0.5 ML 2ND DOSE 0022A $40.00 0031A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 AD26 5X10^10 VP/0.5 ML 1 DOSE 0031A $40.00 0042T CEREBRAL PERFUS ANALYSIS, CT W/CONTRAST 0042T $954.00 0054T BONE SURGERY USING COMPUTER ASSIST, FLURO GUIDED 0054T $640.00 0055T BONE SURGERY USING COMPUTER ASSIST, CT/ MRI GUIDED 0055T $1,188.00 0071T U/S LEIOMYOMATA ABLATE <200 CC 0071T $2,500.00 0075T 0075T PR TCAT PLMT XTRC VRT CRTD STENT RS&I PRQ 1ST VSL 26 26 $2,208.00 0126T CAROTID INT-MEDIA THICKNESS EVAL FOR ATHERSCLER 0126T $55.00 0159T 0159T COMPUTER AIDED BREAST MRI 26 26 $314.00 PR RECTAL TUMOR EXCISION, TRANSANAL ENDOSCOPIC 0184T MICROSURGICAL, FULL THICK 0184T $2,315.00 0191T PR ANT SEGMENT INSERTION DRAINAGE W/O RESERVOIR INT 0191T $2,396.00 01967 ANESTH, NEURAXIAL LABOR, PLAN VAG DEL 01967 $2,500.00 01996 PR DAILY MGMT,EPIDUR/SUBARACH CONT DRUG ADM 01996 $285.00 PR PERQ SAC AGMNTJ UNI W/WO BALO/MCHNL DEV 1/> 0200T NDL 0200T $5,106.00 PR PERQ SAC AGMNTJ BI W/WO BALO/MCHNL DEV 2/> 0201T NDLS 0201T $9,446.00 PR INJECT PLATELET RICH PLASMA W/IMG 0232T HARVEST/PREPARATOIN 0232T $1,509.00 0234T PR TRANSLUMINAL PERIPHERAL ATHERECTOMY, RENAL -

ICD-9-CM Procedures (FY10)

2 PREFACE This sixth edition of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) is being published by the United States Government in recognition of its responsibility to promulgate this classification throughout the United States for morbidity coding. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, published by the World Health Organization (WHO) is the foundation of the ICD-9-CM and continues to be the classification employed in cause-of-death coding in the United States. The ICD-9-CM is completely comparable with the ICD-9. The WHO Collaborating Center for Classification of Diseases in North America serves as liaison between the international obligations for comparable classifications and the national health data needs of the United States. The ICD-9-CM is recommended for use in all clinical settings but is required for reporting diagnoses and diseases to all U.S. Public Health Service and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (formerly the Health Care Financing Administration) programs. Guidance in the use of this classification can be found in the section "Guidance in the Use of ICD-9-CM." ICD-9-CM extensions, interpretations, modifications, addenda, or errata other than those approved by the U.S. Public Health Service and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are not to be considered official and should not be utilized. Continuous maintenance of the ICD-9- CM is the responsibility of the Federal Government. However, because the ICD-9-CM represents the best in contemporary thinking of clinicians, nosologists, epidemiologists, and statisticians from both public and private sectors, no future modifications will be considered without extensive advice from the appropriate representatives of all major users. -

Provider Type 72 Nurse Anesthetist Reimbursement Rates

Provider Type 72 Nurse Anesthetist Reimbursement Rates Updated: May 1, 2015 The information contained in the schedule is made available to provide information and is not a guarantee by the State or the Department or its employees as to the present accuracy of the information contained herein. For example, coverage as well as an actual rate may have been revised or updated and may no longer be the same as posted on the website. Note: Procedure codes with a rate of $0.00 are reimbursed at 62% of Usual and Customary charges unless noted otherwise in Nevada Medicaid policy. CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright © 2008 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Applicable FARS/DFARS apply. CPT is a registered trademark ® of the American Medical Association. Modifier List Anesthesiology Unit Values Proc Code Description Mod Rate 01953 ANESTH BURN EACH 9 PERCENT 21.12 01996 HOSP MANAGE CONT DRUG ADMIN 63.36 10021 FNA W/O IMAGE TC 12.96 10021 FNA W/O IMAGE 26 48.11 10021 FNA W/O IMAGE 61.32 10022 FNA W/IMAGE TC 17.20 10022 FNA W/IMAGE 26 45.87 10022 FNA W/IMAGE 63.07 10040 ACNE SURGERY 45.12 10060 DRAINAGE OF SKIN ABSCESS 49.86 10061 DRAINAGE OF SKIN ABSCESS 103.70 10080 DRAINAGE OF PILONIDAL CYST 51.35 10081 DRAINAGE OF PILONIDAL CYST 108.69 10120 REMOVE FOREIGN BODY 42.87 10121 REMOVE FOREIGN BODY 122.40 10140 DRAINAGE OF HEMATOMA/FLUID 66.06 10160 PUNCTURE DRAINAGE OF LESION 44.62 10180 COMPLEX DRAINAGE WOUND 98.47 11000 DEBRIDE INFECTED SKIN 22.68 11001 DEBRIDE INFECTED SKIN ADD-ON 10.96 11010 DEBRIDE SKIN AT FX -

Compartment Syndrome in Surgical Patients Mary E

Ⅵ CASE REPORTS Anesthesiology 2001; 94:705 © 2001 American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Compartment Syndrome in Surgical Patients Mary E. Warner, M.D.,* Lisa M. LaMaster, B.A.,† Amy K. Thoeming, B.S.N.,† Mary E. Shirk Marienau, M.S., C.R.N.A.,* Mark A. Warner, M.D.‡ COMPARTMENT syndrome is a potentially devastating curred in traumatized limbs or limbs that were subject to postoperative complication that can occur during or ischemia from vascular surgical procedures were ex- after surgery. It is a tissue injury that causes pain, ery- cluded. All surgical episodes must have been performed thema, edema, and hypoesthesia of the nerves in the while patients underwent general or regional anesthesia affected area. In general, fasciotomy must follow clinical or local anesthesia with or without sedation. A single Downloaded from http://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article-pdf/94/4/705/330517/0000542-200104000-00026.pdf by guest on 01 October 2021 diagnosis quickly to prevent permanent tissue damage.1 trained reviewer abstracted all records. Outcomes of If undiagnosed or diagnosed late, it may cause severe these patients at least 2 yr after the index surgeries were rhabdomyolysis, irreversible nerve deficits, loss of limb, obtained. A survey of the impact of the syndrome on or even death. A high proportion of cases have been daily activities, rated as mild, moderate, or major, was reported to occur in patients undergoing surgical proce- obtained from all patients with persistent neurologic dures while in the lithotomy position.1–12 dysfunction of at least 2 years’ duration. Mild impact was Perioperative compartment syndrome for which there defined as “often noticeable but not associated with any is no readily apparent cause (e.g., secondary to trauma or limitation of activities of daily living.” Moderate impact arterial embolism after vascular surgery) is not well- was defined as “always noticeable and associated with understood. -

The Use of Vacuum Assisted Closure (VAC ) in Soft Tissue Injuries After High Energy Pelvic Trauma

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2007 The use of vacuum assisted closure (VAC™) in soft tissue injuries after high energy pelvic trauma Labler, Ludwig ; Trentz, Otmar Abstract: Background: Application of vacuum-assisted closure (VAC™) in soft tissue defects after high- energy pelvic trauma is described as a retrospective study in a level one trauma center. Materials and methods: Between 2002 and 2004, 13 patients were treated for severe soft tissue injuries in the pelvic region. All musculoskeletal injuries were treated with multiple irrigation and debridement procedures and broad-spectrum antibiotics. VAC™ was applied as a temporary coverage for defects and wound conditioning. Results: The injuries included three patients with traumatic hemipelvectomies. Seven patients had pelvic ring fractures with five Morel-Lavallee lesions and two open pelviperineal trauma. One patient suffered from an open iliac crest fracture and a Morel-Lavallee lesion. Two patients sustained near complete pertrochanteric amputations of the lower limb. The average injury severity score was 34.1 ± 1.4. The application of VAC™ started in average 3.8 ± 0.4days after trauma and was used for 15.5 ± 1.8days. The dressing changes were performed in average every 3days. One patient (8%) with a traumatic hemipelvectomy died in the course of treatment due to septic complications. Conclusion: High-energy trauma causing severe soft tissues injuries requires multiple operative debridements to prevent high morbidity and mortality rates. The application of VAC™ as temporary coverage of large tissue defects in pelvic regions supports wound conditioning and facilitates the definitive wound closure DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-006-0090-0 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-156487 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Labler, Ludwig; Trentz, Otmar (2007). -

Reconstruction and Management of Traumatic Hemipelvectomy: a Case Report

edicine: O M p y e Yıldırım et al., Emergency Med 2018, 8:4 c n n A e c g c r DOI: 10.4172/2165-7548.1000381 e e s Emergency Medicine: s m E ISSN: 2165-7548 Open Access Case Report Open Access Reconstruction and Management of Traumatic Hemipelvectomy: A Case Report Mehmet Emin Cem Yıldırım*, Mehmet Dadaci, Zikrullah Baycar and Bilsev İnce Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Necmettin Erbakan University, School of the Medicine, Konya, Turkey Abstract Traumatic amputation refers to loss of a part or entire organ, such as limbs, ears, penis from the body by an accident or trauma. The extremities are important for numerous activities in our daily lives. Nutrition, movement and working are just a few of daily functions. Loss of an extremity is a destructive trauma with physical and psychological effects on the patient. In addition, it has serious economic consequences due to the loss of labor, health expenditures and rehabilitation process. Keywords: Traumatic amputation; Hemipelvic The urine flow was controlled by a catheter inserted by the urology department. The bladder was visible in the area of injury, and there Introduction was no perforation. As the plastic surgery team, we also participated Major amputations are serious life-threatening injuries, and a to the operation and first, we performed debridement of the necrotic multidisciplinary approach reduces morbidity and mortality in major tissues. Scrotum defect was repaired with local flaps. For the large amputations from trauma [1-4]. Among those living with limb loss, defect in the penile urethra, the avulsedive urethral mucosa was re- the main causes are vascular disease (54%) – including diabetes and shaped, wrapped to the catheter, passed through the scrotum, and peripheral arterial disease – trauma (45%) and cancer (less than 2%) anastomosed. -

Survival Rate and Perioperative Data of Patients Who Have

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Couto et al. World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2016) 14:255 DOI 10.1186/s12957-016-1001-7 RESEARCH Open Access Survival rate and perioperative data of patients who have undergone hemipelvectomy: a retrospective case series Alfredo Guilherme Haack Couto1* , Bruno Araújo2, Roberto André Torres de Vasconcelos3, Marcos José Renni4, Clóvis Orlando Da Fonseca5 and Ismar Lima Cavalcanti1,6 Abstract Background: Hemipelvectomy is a major orthopedic surgical procedure indicated in specific situations. Although many studies discuss surgical techniques for hemipelvectomy, few studies have presented survival data, especially in underdeveloped countries. Additionally, there is limited information on anesthesia for orthopedic oncologic surgeries. The primary aim of this study was to determine the survival rate after hemipelvectomy, and the secondary aims were to evaluate anesthesia and perioperative care associated with hemipelvectomy and determine the influence of the surgical technique (external hemipelvectomy [amputation] or internal hemipelvectomy [limb sparing surgery]) on anesthesia and perioperative care in Brazil. Methods: This retrospective case series collected data from 35 adult patients who underwent hemipelvectomy between 2000 and 2013. Survival rates after surgery were determined, and group comparisons were performed using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test. Mantel–Cox test and multiple linear regression analysis with stepwise forward selection were performed for univariate and multivariate analyses, respectively. Results: Mean survival time was 32.8 ± 4.6 months and 5-year survival rate was 27 %. Of the 35 patients, 23 patients (65.7 %) underwent external hemipelvectomy and 12 patients (34.3 %) underwent internal hemipelvectomy. -

FORDS Manual 2003

ACILITY ONCOLOGY REGISTRY DATA STANDARDS FACILITY ONCOLOGY REGISTRY DATA STANDARDS © 2002 AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Preface .............................................................. vii Acknowledgments ......................................................... xiii SECTION ONE: Case Eligibility, Cancer Identification, and Overview of Coding Principles .................................... 1–28 Case Eligibility ......................................................... 3 Malignancies Required by the CoC to be Accessioned, Abstracted, and Followed ... 3 Reportable-by-Agreement Cases ........................................ 4 Cases Not Required by the CoC to be Accessioned .......................... 4 Class of Case ....................................................... 4 Cancer Identification .................................................... 7 Unique Patient Identifier Codes ......................................... 7 Cancer Identification ................................................. 7 Overview of Coding Principles ............................................. 15 Patient Address and Residency Rules ..................................... 15 Comorbidities and Complications ........................................ 15 Stage of Disease at Initial Diagnosis ...................................... 16 First Course of Treatment .............................................. 18 Case Administration .................................................. 26 SECTION TWO: Coding Instructions ........................................29–235 -

Noncyclic Chronic Pelvic Pain Therapies for Women: Comparative Effectiveness Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 41

Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 41 Noncyclic Chronic Pelvic Pain Therapies for Women: Comparative Effectiveness Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 41 Noncyclic Chronic Pelvic Pain Therapies for Women: Comparative Effectiveness Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 540 Gaither Road Rockville, MD 20850 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. 290-2007-10065-I Prepared by: Vanderbilt Evidence-based Practice Center Nashville, Tennessee Investigators: Jeff Andrews, M.D. Amanda Yunker, D.O., M.S.C.R. W. Stuart Reynolds, M.D. Frances E. Likis, Dr.P.H., N.P., C.N.M. Nila A. Sathe, M.A., M.L.I.S. Rebecca N. Jerome, M.L.I.S., M.P.H. AHRQ Publication No. 11(12)-EHC088-EF January 2012 This report is based on research conducted by the Vanderbilt Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) under contract to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD (Contract No. HHSA 290-2007-10065-I). The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors, who are responsible for its contents; the findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Therefore, no statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The information in this report is intended to help health care decisionmakers—patients and clinicians, health system leaders, and policymakers, among others—make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. This report is not intended to be a substitute for the application of clinical judgment.