20 Posterior Flap Hemipelvectomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Practice Guideline for Limb Salvage Or Early Amputation

Limb Salvage or Early Amputation Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline Adopted by: The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Board of Directors December 6, 2019 Endorsed by: Please cite this guideline as: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Limb Salvage or Early Amputation Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/quality-and-practice-resources/dod/ lsa-cpg-final-draft-12-10-19.pdf Published December 6, 2019 View background material via the LSA CPG eAppendix Disclaimer This clinical practice guideline was developed by a physician volunteer clinical practice guideline development group based on a formal systematic review of the available scientific and clinical information and accepted approaches to treatment and/or diagnosis. This clinical practice guideline is not intended to be a fixed protocol, as some patients may require more or less treatment or different means of diagnosis. Clinical patients may not necessarily be the same as those found in a clinical trial. Patient care and treatment should always be based on a clinician’s independent medical judgment, given the individual patient’s specific clinical circumstances. Disclosure Requirement In accordance with AAOS policy, all individuals whose names appear as authors or contributors to this clinical practice guideline filed a disclosure statement as part of the submission process. All panel members provided full disclosure of potential conflicts of interest prior to voting on the recommendations contained within this clinical practice guideline. Funding Source This clinical practice guideline was funded exclusively through a research grant provided by the United States Department of Defense with no funding from outside commercial sources to support the development of this document. -

En Bloc Resection of Extra-Peritoneal Soft Tissue Neoplasms Incorporating a Type III Internal Hemipelvectomy: a Novel Approach Sanjay S Reddy1* and Norman D Bloom2

Reddy and Bloom World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2012, 10:222 http://www.wjso.com/content/10/1/222 WORLD JOURNAL OF SURGICAL ONCOLOGY REVIEW Open Access En bloc resection of extra-peritoneal soft tissue neoplasms incorporating a type III internal hemipelvectomy: a novel approach Sanjay S Reddy1* and Norman D Bloom2 Abstract Background: A type III hemipelvectomy has been utilized for the resection of tumors arising from the superior or inferior pubic rami. Methods: In eight patients, we incorporated a type III internal hemipelvectomy to achieve an en bloc R0 resection for tumors extending through the obturator foramen or into the ischiorectal fossa. The pelvic ring was reconstructed utilizing marlex mesh. This allowed for pelvic stability and abdominal wall reconstruction with obliteration of the obturator space to prevent herniations. Results: All eight patients had an R0 resection with an overall survival of 88% and with average follow up of 9.5 years. Functional evaluation utilizing the Enneking classification system, which evaluates motion, pain, stability and strength of the affected extremity, revealed a 62% excellent result and a 37% good result. No significant complications were associated with the operative procedure. Marlex mesh reconstruction provided pelvic stability and eliminated all hernial defects. Conclusion: The superior and inferior pubic rami provide a barrier to a resection for tumors that arise in the extra-peritoneal pelvis extending through the obturator foramen or ischiorectal fossa. Incorporating a type III internal -

Reducing Amputation Rates After Severe Frostbite JENNIFER TAVES, MD, and THOMAS SATRE, MD, University of Minnesota/St

FPIN’s Help Desk Answers Reducing Amputation Rates After Severe Frostbite JENNIFER TAVES, MD, and THOMAS SATRE, MD, University of Minnesota/St. Cloud Hospital Family Medicine Resi- dency Program, St. Cloud, Minnesota Help Desk Answers pro- Clinical Question in the tPA plus iloprost group with severe vides answers to questions submitted by practicing Is tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) effec- disease and only three and nine digits in the family physicians to the tive in reducing digital amputation rates in other treatment arms. Thus, no conclusions Family Physicians Inquiries patients with severe frostbite? can be reached about the effect of tPA plus Network (FPIN). Members iloprost compared with iloprost alone. of the network select Evidence-Based Answer questions based on their A 2007 retrospective cohort trial evalu- relevance to family medi- In patients with severe frostbite, tPA plus a ated the use of tPA in six patients with severe cine. Answers are drawn prostacyclin may be used to decrease the risk of frostbite.2 After rapid rewarming, patients from an approved set of digital amputation. (Strength of Recommen- underwent digital angiography, and those evidence-based resources and undergo peer review. dation [SOR]: B, based on a single randomized with significant perfusion defects received controlled trial [RCT].) tPA can be used alone intraarterial tPA (0.5 to 1 mg per hour IV The complete database of evidence-based ques- and is associated with lower amputation rates infusion) and heparin (500 units per hour tions and answers is compared with local wound care. (SOR: C, IV infusion) for up to 48 hours. Patients who copyrighted by FPIN. -

Use of Anterolateral Thigh Flap for Reconstruction of Traumatic Bilateral Hemipelvectomy After Major Pelvic Trauma

Al‑wageeh et al. surg case rep (2020) 6:247 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792‑020‑01009‑2 CASE REPORT Open Access Use of anterolateral thigh fap for reconstruction of traumatic bilateral hemipelvectomy after major pelvic trauma: a case report Saleh Al‑wageeh1 , Faisal Ahmed2* , Khalil Al‑naggar3 , Mohammad Reza Askarpour4 and Ebrahim Al‑shami5 Abstract Background: Major pelvic trauma (MPT) with traumatic hemipelvectomy (THP) is rare, but it is a catastrophic health problem caused by high‑energy injury leading to separation of the lower extremity from the axial skeleton, which is associated with a high incidence of intra‑abdominal and multi‑systemic injuries. THP is generally performed as a lifesaving protocol to return the patient to an active life. Case report: A 12‑year male patient exposed to major pelvic trauma with bilateral THP survived the trauma and mul‑ tiple lifesaving operations. The anterolateral thigh fap is the method used for wound reconstruction. The follow‑up was ended with colostomy and cystostomy with wheelchair mobilization. To the best of our knowledge, there have been a few bilateral THP reports, and our case is the second one to be successfully treated with an anterolateral thigh fap. Conclusion: MPT with THP is the primary cause of death among trauma patients. Life‑threatening hemorrhage is the usual cause of death, which is a strong indication for THP to save life. Keywords: Amputation, Hemipelvectomy, Myocutaneous fap, Reconstruction, Trauma Introduction A few victims survive these injuries, and the actual Major pelvic trauma (MPT) associated with traumatic incidence is unknown, but it is usually underestimated hemipelvectomy (THP) was described frst by Turnbull in [3]. -

Department of Veterans Affairs 8320-01

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 02/22/2013 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2013-04134, and on FDsys.gov DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS 8320-01 38 CFR Part 17 RIN 2900-AO21 Criteria for a Catastrophically Disabled Determination for Purposes of Enrollment AGENCY: Department of Veterans Affairs. ACTION: Proposed rule. SUMMARY: The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) proposes to amend its regulation concerning the manner in which VA determines that a veteran is catastrophically disabled for purposes of enrollment in priority group 4 for VA health care. The current regulation relies on specific codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®). We propose to state the descriptions that would identify an individual as catastrophically disabled, instead of using the corresponding ICD-9-CM and CPT® codes. The revisions would ensure that our regulation is not out of date when new versions of those codes are published. The revisions would also broaden some of the descriptions for a finding of catastrophic disability. Additionally, we would eliminate the Folstein Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) as a criterion for determining whether a veteran meets the definition of catastrophically disabled, because we have determined that the MMSE is no longer a necessary clinical assessment tool. DATES: Comments on the proposed rule must be received by VA on or before [Insert date 60 days after date of publication in the FEDERAL REGISTER]. ADDRESSES: Written comments may be submitted through http://www.regulations.gov; by mail or hand-delivery to the Director, Regulations Management (02REG), Department of Veterans Affairs, 810 Vermont Avenue, NW, Room 1068, Washington, DC 20420; or by fax to (202) 273-9026. -

Lower Limb Amputation Booklet

A Resource Guide For Lower Limb Amputation Table of Contents Reasons for Amputation . 3 Emotional Adjustments to Amputation . 4 Caring for your Residual Limb . 6 Skin Care Shaping Contracture Management Pressure Relief Sound Limb Preservation Skin Problems Associated with Amputation . 8 Phantom Limb Sensation/Pain . 10 Physical Therapy Following Amputation . 12 Stretches Exercises Preparing for Prosthetic Evaluation . 18 Prosthetic Options . 19 Socket Suspension Knee Feet Caring for your Prosthetic . .. 23 Resources . 24 Websites . 26 Reasons for Amputation There are many reasons for amputations; these are some of the more common causes: Poor Circulation The most common reason for amputation is peripheral artery disease, which leads to poor circulation due to narrowing of the arteries . Without blood flowing throughout the entire limb, the tissues are deprived of oxygen and nutrients . Without oxygen and nutrients, the tissue may begin to die, and this may lead to infection . If the infection becomes too severe, there may be need for amputation . Non-healing wounds or infection People with decreased sensation in the lower extremities may develop wounds and be unaware of these wounds until the wound site has become severe and even infected . If the wound is not responding to antibiotics, the wound may become too severe and there may be need for amputation . Trauma Many types of trauma may result in limb loss, these include, but are not limited to: » Motor vehicle accident » Serious burn » Machinery Accidents » Severe fractures due to falls » Frostbite The most important aspect of many health concerns is prevention . If you have lost a limb due to complications with impaired sensation or circulation, you are at a higher risk for further injury, or new injury to your sound, or intact, limb . -

Amputation Explained Download

2 Amputation Explained CONTENTS About Amputation 03 How Common Are Amputations? 03 General Causes Explained 04 Outlook 06 Complications of Amputation 06 Psychological Impact of Amputation 07 Lower and Upper Limb Amputations 09 How an Amputation is Performed 10 Pre-Operative Assessment 10 Surgery 11 Recovering from Amputation 12 Going Home 15 Contact Us 16 About Amputation This leaflet is part of a series produced by Blesma for your general information. It is designed for anyone scheduled for amputation or further amputations, but is useful for anyone who has had surgery to remove a limb or limbs, or part of a limb or limbs. It is hoped that this information will allow people to monitor their own health and seek early advice and intervention from an appropriate medical practitioner. Any questions brought up by this leaflet should be raised with a doctor. How Common Are Amputations? Between 5,000 and 6,000 major limb amputations are carried out in the UK every year. The most common reason for amputation is a loss of blood supply to the affected limb (critical ischemia), which accounts for 70 per cent of lower limb amputations. Trauma is the most common reason for upper limb amputations, and accounts for 57 per cent. People with either Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes are particularly at risk, and are 15 times more likely to need an amputation than the general population. This is because diabetes leads to high blood glucose levels that can damage blood vessels, leading to a restriction in blood supply. More than half of all amputations are performed in people aged 70 or over, while men are twice as likely to need an amputation as women. -

Penile and Genital Injuries

Urol Clin N Am 33 (2006) 117–126 Penile and Genital Injuries Hunter Wessells, MD, FACS*, Layron Long, MD Department of Urology, University of Washington School of Medicine and Harborview Medical Center, 325 Ninth Avenue, Seattle, WA 98104, USA Genital injuries are significant because of their Mechanisms association with injuries to major pelvic and vas- The male genitalia have a tremendous capacity cular organs that result from both blunt and pen- to resist injury. The flaccidity of the pendulous etrating mechanisms, and the chronic disability portion of the penis limits the transfer of kinetic resulting from penile, scrotal, and vaginal trauma. energy during trauma. In contrast, the fixed Because trauma is predominantly a disease of portion of the genitalia (eg, the crura of the penis young persons, genital injuries may profoundly in relation to the pubic rami, and the female affect health-related quality of life and contribute external genitalia in their similar relationships to the burden of disease related to trauma. Inju- with these bony structures) are prone to blunt ries to the female genitalia have additional conse- trauma from pelvic fracture or straddle injury. quences because of the association with sexual Similarly, the erect penis becomes more prone to assault and interpersonal violence [1]. Although injury because increases in pressure within the the existing literature has many gaps, a recent penis during bending rise exponentially when the Consensus Group on Genitourinary Trauma pro- penis is rigid (up to 1500 mm Hg) as opposed to vided an overview and reference point on the sub- flaccid [6]. Injury caused by missed intromission ject [2]. -

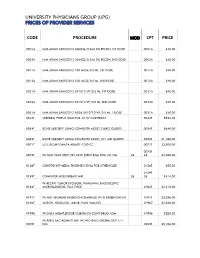

Code Procedure Cpt Price University Physicians Group

UNIVERSITY PHYSICIANS GROUP (UPG) PRICES OF PROVIDER SERVICES CODE PROCEDURE MOD CPT PRICE 0001A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 30MCG/0.3ML DIL RECON 1ST DOSE 0001A $40.00 0002A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 30MCG/0.3ML DIL RECON 2ND DOSE 0002A $40.00 0011A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 100 MCG/0.5 ML 1ST DOSE 0011A $40.00 0012A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 100 MCG/0.5 ML 2ND DOSE 0012A $40.00 0021A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 5X1010 VP/0.5 ML 1ST DOSE 0021A $40.00 0022A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 5X1010 VP/0.5 ML 2ND DOSE 0022A $40.00 0031A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 AD26 5X10^10 VP/0.5 ML 1 DOSE 0031A $40.00 0042T CEREBRAL PERFUS ANALYSIS, CT W/CONTRAST 0042T $954.00 0054T BONE SURGERY USING COMPUTER ASSIST, FLURO GUIDED 0054T $640.00 0055T BONE SURGERY USING COMPUTER ASSIST, CT/ MRI GUIDED 0055T $1,188.00 0071T U/S LEIOMYOMATA ABLATE <200 CC 0071T $2,500.00 0075T 0075T PR TCAT PLMT XTRC VRT CRTD STENT RS&I PRQ 1ST VSL 26 26 $2,208.00 0126T CAROTID INT-MEDIA THICKNESS EVAL FOR ATHERSCLER 0126T $55.00 0159T 0159T COMPUTER AIDED BREAST MRI 26 26 $314.00 PR RECTAL TUMOR EXCISION, TRANSANAL ENDOSCOPIC 0184T MICROSURGICAL, FULL THICK 0184T $2,315.00 0191T PR ANT SEGMENT INSERTION DRAINAGE W/O RESERVOIR INT 0191T $2,396.00 01967 ANESTH, NEURAXIAL LABOR, PLAN VAG DEL 01967 $2,500.00 01996 PR DAILY MGMT,EPIDUR/SUBARACH CONT DRUG ADM 01996 $285.00 PR PERQ SAC AGMNTJ UNI W/WO BALO/MCHNL DEV 1/> 0200T NDL 0200T $5,106.00 PR PERQ SAC AGMNTJ BI W/WO BALO/MCHNL DEV 2/> 0201T NDLS 0201T $9,446.00 PR INJECT PLATELET RICH PLASMA W/IMG 0232T HARVEST/PREPARATOIN 0232T $1,509.00 0234T PR TRANSLUMINAL PERIPHERAL ATHERECTOMY, RENAL -

Frostbite: a Practical Approach to Hospital Management

Handford et al. Extreme Physiology & Medicine 2014, 3:7 http://www.extremephysiolmed.com/content/3/1/7 REVIEW Open Access Frostbite: a practical approach to hospital management Charles Handford1, Pauline Buxton2, Katie Russell3, Caitlin EA Imray4, Scott E McIntosh5, Luanne Freer6,7, Amalia Cochran8 and Christopher HE Imray9,10* Abstract Frostbite presentation to hospital is relatively infrequent, and the optimal management of the more severely injured patient requires a multidisciplinary integration of specialist care. Clinicians with an interest in wilderness medicine/ freezing cold injury have the awareness of specific potential interventions but may lack the skill or experience to implement the knowledge. The on-call specialist clinician (vascular, general surgery, orthopaedic, plastic surgeon or interventional radiologist), who is likely to receive these patients, may have the skill and knowledge to administer potentially limb-saving intervention but may be unaware of the available treatment options for frostbite. Over the last 10 years, frostbite management has improved with clear guidelines and management protocols available for both the medically trained and winter sports enthusiasts. Many specialist surgeons are unaware that patients with severe frostbite injuries presenting within 24 h of the injury may be good candidates for treatment with either TPA or iloprost. In this review, we aim to give a brief overview of field frostbite care and a practical guide to the hospital management of frostbite with a stepwise approach to thrombolysis and prostacyclin administration for clinicians. Keywords: Frostbite, Hypothermia, Rewarming, Thrombolysis, Heparin, TPA, Iloprost Review physiologic response to cold injuries was similar to that of Introduction burn injuries and recognized that warming frozen tissue Frostbite is a freezing, cold thermal injury, which occurs was advantageous for recovery. -

Cross-Sectional Imaging in the Evaluation of Osteogenic Sarcoma: MRI and CT

Cross-sectional Imaging in the Evaluation of Osteogenic Sarcoma: MRI and CT By Leanne L. Seeger, Jeffrey J. Eckardt, and Lawrence W. Bassett EFORE the advent of cross-sectional scan- for treatment. Magnetic resonance imaging and B ning techniques, imaging of malignant bone CT image acquisition should address specific tumors was confined to plain radiography and issues that are important to the surgeon and radionuclide bone scanning. While radiography should be tailored according to tumor location remains the primary imaging modality for differ- and proposed surgical treatment, whether it be ential diagnosis, magnetic resonance imaging amputation or resection with limb salvage proce- (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) have dure. had a profound impact on the preoperative stag- The following discussion reflects the scanning ing evaluation of bone tumors and their response principles and techniques we use for evaluating to therapy. patients with OGS both preoperatively and post- In this article we will define the role of MRI operatively. This was derived from both our own and CT in the work-up of the patient with known experience and the experience of others as re- osteogenic sarcoma (OGS), stressing imaging ported in the literature. ‘-’ Regional differences in strategies that optimize information available to the management of patients with malignant bone the clinician and assist in therapy planning. In tumors may alter this procedure. To become order to achieve these optimal factors, communi- familiar with local treatment protocols, commu- cation with the referring physician and review of nicate directly with the surgeon who will ulti- available radiographs and radionuclide bone scans mately be responsible for treatment. -

ICD-9-CM Procedures (FY10)

2 PREFACE This sixth edition of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) is being published by the United States Government in recognition of its responsibility to promulgate this classification throughout the United States for morbidity coding. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, published by the World Health Organization (WHO) is the foundation of the ICD-9-CM and continues to be the classification employed in cause-of-death coding in the United States. The ICD-9-CM is completely comparable with the ICD-9. The WHO Collaborating Center for Classification of Diseases in North America serves as liaison between the international obligations for comparable classifications and the national health data needs of the United States. The ICD-9-CM is recommended for use in all clinical settings but is required for reporting diagnoses and diseases to all U.S. Public Health Service and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (formerly the Health Care Financing Administration) programs. Guidance in the use of this classification can be found in the section "Guidance in the Use of ICD-9-CM." ICD-9-CM extensions, interpretations, modifications, addenda, or errata other than those approved by the U.S. Public Health Service and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are not to be considered official and should not be utilized. Continuous maintenance of the ICD-9- CM is the responsibility of the Federal Government. However, because the ICD-9-CM represents the best in contemporary thinking of clinicians, nosologists, epidemiologists, and statisticians from both public and private sectors, no future modifications will be considered without extensive advice from the appropriate representatives of all major users.