UMT Education Review (UER) Volume No.1, Issue No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Documentation and Description

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 17. Editor: Peter K. Austin Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan ZUBAIR TORWALI Cite this article: Torwali, Zubair. 2020. Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description 17, 44- 65. London: EL Publishing. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/181 This electronic version first published: July 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan Zubair Torwali Independent Researcher Summary Indigenous communities living in the mountainous terrain and valleys of the region of Gilgit-Baltistan and upper Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, northern -

BANJARA STASTICAL REPORT KARNATKA STATE Report

BANJARA STASTICAL REPORT KARNATKA STATE Report Submitted to Mr. Rahul Gandhi General Secretary All India Congress Committee New Delhi BY Dr. Chandrashekar Naik Dr.D Paramesha Naik B.E,M.Tech,M.B.A,M.Phil Ph.D M.Sc, M.Phil, Ph.D, FISEC Congress & Banjara – Activist Congress & Banjara – Activist Mobile: +91-9379945100 Mobile: +91-9844250997 [email protected] [email protected] 2012 About Banjaras The Banjaras are the largest and historic formed group in India and also known as Lambadi or Lambani. The Banjara people are a people who speak lambadi or Lambani. All gypsy languages are linked linguistically, stemming from ancient Sanskrit and belonging to the North Indo-Aryan language family. Lambadi is the heart language of the Banjara, but it has no written script. The Banjara speak a second language of the state they live in and adopt that script. They are listed under 53 different names. Historically, these are the root Gypsies of earth. During the British colonial rule, these gypsy nomads of India were given the name Banjara, but they call themselves Ghor. The Banjaras are a colourful, versatile and one of the largest people groups of India, inhabiting most of the districts in India. The Banjara are a sturdy, ambitious people and have a light complexion. The Banjara were historically nomadic, keeping cattle, trading salt and transporting goods. Most of these people now have settled down to farming and various types of wage labour. Their habits of living in isolated groups away from other, which was a characteristic of their nomadic days, still persist. -

O)){|P in SOCIOLOGY

SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEPRIVATION OF MUSLIMS IN LOCK AND LAC INDUSTRIES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ALIGARH AND HYDERABAD ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF IBoctor of $i)tlos;o)){|p IN SOCIOLOGY BY SADAF NASIR UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ARDUL MATIN DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND ?50CIAL WORK ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2011 ABSTRACT The title of the thesis is 'Socio-Economic Deprivation of MusUms in Lock and Lac Industries: A Comparative Study of AUgarh and Hyderabad'. The focus of the study is to examine dispossession and loss of downtrodden Muslim workers of Aligarh lock industry and Hyderabad lac industry respectively. Deprivation of Muslim workers have been examined in terms of (a) material deprivation, (b) Social deprivation, (c) multiple deprivation viz. low income, poor housing and unemployment. The present study is primarily based on field work carried out during April 2009 to March 2010 in Aligarh (U.P.) and Hyderabad (A.P.). The objectives of this study are to explore the socio-economic deprivation of Muslims in Aligarh Lock Industry (Uttar Pradesh) and Hyderabad Lac Industry (Andhra Pradesh) within the fi-amework of relative deprivation. Important issues in this study are as follows: (1) Selected socio-economic indicators viz., family backgroimd, education, income, housing status, health and hygiene and political dimension of the respondents are to be assessed in Aligarh and Hyderabad. (2) To explore the causes and consequences of socio-economic deprivation of Muslims in the lock and Lac industries. (3) To examine, whether the Muslim children supplement to their family income? (3) To assess how and why the Muslims in lock and lac industry are socially and economically deprived. -

Literature Review in India: - a Case Study of Gujjar and Bakerwals

Mukt Shabd Journal ISSN NO : 2347-3150 Literature Review in India: - A Case Study of Gujjar and Bakerwals Dr. Raja Shahid Mughal Abstract Gujjars and Bakerwals are two names of one tribe popularly known as Gujjars in Indian sub- continent. Gujjars form an important ethnic and linguistic group. A country like India is a place to a variety of population with their separate culture, traditions and living styles. India is a home to almost more than half of the world’s tribal population. Gujrat, the state of India, was once called as Gujjar- Rashtra, which indicate the meaning Kingdom of Gujjar’s. From this area Gujjar’s established their kingdom and spread over other parts of the country.In this paper I describe the almost whole review about the literature of Gujjar and Bakerwals . Keyword:- Culture, Nomadic Life, Tribals, Gujari (Gojri), Gujjar Bakarwal tribals. Introduction Various studies have been conducted to discuss and analyze the different dimensions of the tribal life in India. Therefore, available relevant studies have been critically reviewed. Hudson (1922) in his book entitled “The Primitive Culture of India” traced the complex historical evaluation of various tribes of India and Hulton (1941) examined their socio- cultural condition. Ghurye (1943) argued that the tribals were backward caste Hindus. He at that time also held that they should be given equal status like the other Hindus. Majumdar (1944) following Ghurye‟s argument suggested that the cultural identity of tribals should be secured for which he stressed that there should be 'selected integration' of the tribals. Explaining it in detail he further held that only those people should be permitted to enter in this community who have relevance with tribal life. -

Indigenous Peoples Planning Framework

Indigenous People Planning Framework (IPPF) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Pakistan Hydro-Meteorological & Ecosystem Restoration Project National Disaster Risk Management Fund Public Disclosure Authorized Pakistan Hydro-Meteorological and Ecosystem Restoration Project Acronyms and Abbreviations AKRSP Aga Khan Rural Support Programme BP Bank Policy CPS Country Partnership Strategy EA Executive Agency EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ESM Environmental and Social Management ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework FIP Fund Implementation Partner FPIC Free Prior Informed Consultation GRC Grievance Redress Committee GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism HEIS High Efficiency Irrigation System IA Implementing Agency IDA International Development Association ILO International Labor Organization IP Indigenous People IPP Indigenous Peoples Plan IPPF Indigenous Peoples Planning Framework ITP Indigenous Tribal People KP Khyber Pakhtunkhwa LAR Land Acquisition & Resettlement Error! Use the Home tab to apply Head to the text that you want to appear here. Pakistan Hydro-Meteorological and Ecosystem Restoration Project LGRC Local Grievance Redress Committee LSO Local Support Organization M&E Monitoring and Evaluation NDRA National Database Registration Authority NGO Non-Governmental Organization OFM On Farm Management OP Operational Policy PD Project Director PDO Project Development Objectives PIU Project Implementation Unit PPAF Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund RAP Resettlement Action Plan UC Union Council UN United Nation UNDRIP United Nation Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People VC Village Council Error! Use the Home tab to apply Head to the text that you want to appear here. Pakistan Hydro-Meteorological and Ecosystem Restoration Project Glossary Ancestral Domain Ancestral domain or ancestral lands refer to the lands, territories and resources of indigenous peoples. -

Shyam Singh Shashi. Nomads of India. New Delhi: National Book Trust, India, 2015

Book Reviews 145 Shyam Singh Shashi. Nomads of India. New Delhi: National Book Trust, India, 2015. PB. pp. 63. Price 45. ISBN: 978-81-237-7413-8. (Translated by C.R. Biswas and vetted by the author.) Reviewed by Vijay Kumar Roy* Padma Shri Dr. Shyam Singh Shashi is an eminent Hindi poet, anthropologist and social scientist. He has Encyclopedia of Humanities and Social Sciences (50 volumes), Encyclopedia of Indian Tribes (12 volumes), Encyclopedia of World Women (10 volumes) and Encyclopedia Indica (150 volumes); many poetry collections and other important books to his credit. The present book, Nomads of India (2015) is a great contribution to the knowledge of mankind. The book presents anthropological, historical and sociocultural studies of nomadic communities of India. This is the result of extensive studies on these communities in India and abroad by the writer. In the preface of the book the writer mentions about his amazement that we usually talk about the great world travellers – Columbus, Vasco-De-Gama, Fi-yan and When-Sang but not those nomads who have been travelling since ages from the Himalayas to Kanyakumari and also to different countries. They are neglected and disadvantaged groups of the society. The writer intends to create “an awareness among the young readers about the forgotten and neglected communities and to work for their well- being in missionary spirit.” (6) The book has ten chapters, each dealing with different groups and kinds of nomads living in different parts of India and the world. In the first chapter, the writer finds that nomads are ‘a proud and self-reliant community’. -

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads - A Literature Review Anita Sharma CREATE PATHWAYS TO ACCESS Research Monograph No. 58 January 2011 University of Sussex Centre for International Education The Consortium for Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE) is a Research Programme Consortium supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Its purpose is to undertake research designed to improve access to basic education in developing countries. It seeks to achieve this through generating new knowledge and encouraging its application through effective communication and dissemination to national and international development agencies, national governments, education and development professionals, non-government organisations and other interested stakeholders. Access to basic education lies at the heart of development. Lack of educational access, and securely acquired knowledge and skill, is both a part of the definition of poverty, and a means for its diminution. Sustained access to meaningful learning that has value is critical to long term improvements in productivity, the reduction of inter- generational cycles of poverty, demographic transition, preventive health care, the empowerment of women, and reductions in inequality. The CREATE partners CREATE is developing its research collaboratively with partners in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The lead partner of CREATE is the Centre for International Education at the University of Sussex. The partners are: -

Final Program

Institute for Anthropological Research, Zagreb, Croatia Croatian Anthropological Society Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana Slovenian Ethnological and Anthropological Association INTER CONGRESS World anthropologies and privatization of knowledge: engaging anthropology in public 4-9 May 2016 / Hotel Dubrovnik Palace / Dubrovnik, Croatia FINAL PROGRAM WELCOME ADDRESS It is our great pleasure to welcome you to the International Union of Anthropological and Ethno- logical Sciences’s (IUAES) Inter-Congress World anthropologies and privatization of knowledge: engaging anthropology in public in Dubrovnik, Croatia! This year’s IUAES Inter-congress is intended to provide participants with an opportunity to dis- cuss and develop a comprehensive insight into the diversity of ways in which scientific research and scholarship can be, has been or will be employed to understand and engage in social pro- cesses and to consider the various risks brought about by new technologies, global economic development, changes in the world’s demographic structure and the increased complexity of managing contemporary societies. In particular, it will consider the extent to which and how privatization of knowledge has become a serious global socio-political threat, not only because it often precludes the general public from knowing about or understanding important new insights in scientific research and scholarship, but also because it results in knowledge being more and more unevenly distributed around the globe to the extent that, if knowledge is privatized, the global south will increasingly be deprived of access to new knowledge and the potential to use it to improve life. The ethnological and anthropological sciences encompass an abundance of different research fields and perspectives, particularly as they develop in diverse parts of the world. -

Gujjar Bakarwals - the Eco-Friendly Tribals of Jammu and Kashmir Since Centuries

Bull.lnd.Hist.Med Vol. XXVIII - 1998 pp 139 to 145 GUJJAR BAKARWALS - THE ECO-FRIENDLY TRIBALS OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR SINCE CENTURIES ANIL KUMAR* & NARESH KUMAR** ABSTRACT According to the ecological approach, health represents the adjustment of the human organism to his environment. The man of today is living in a highly complicated environment and his health problem is more complicated as he is becoming more ingenious. But, there are people who with their strong social structure are living in healthy relationship with their environment and are enjoying the transformation of their rich genetic potentialities into phenotypic realities since centuries. They are Gujjar Bakarwal tribals of Jammu and Kashmir. Here, in this article, the traditionally hard life style of these tribals with reference to their social, physical and Biological environmental factors which make them eco-friendly has been discussed. Introduction defined as ecology and human ecology The quest for health is as old as the is concerned with the broad setting of history of mankind from the man of the man in his environment. The basic theme primitive age to the man of today, the of ecology is that everything is related to wheel of time has taken innumerable everything else. According to the turns. The values, patterns and ecological approach the health is a state technologies have changed altogether. of dynamic equilibrium or adjustment But even today every time we are faced between man and his environment. The with any harship pertaining to health or environment is not merely the air, water life - we turn back to nature to find a and soil but also the social and the suitable answer. -

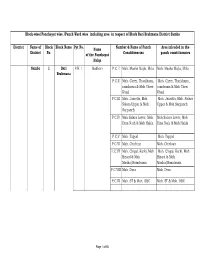

Block-Wise/Panchayat Wise /Panch Ward Wise Including Area in Respect of Block Bari Brahmana District Samba

Block-wise/Panchayat wise /Panch Ward wise including area in respect of Block Bari Brahmana District Samba District Name of Block Block Name Pyt No. Name Number & Name of Panch Area inlcuded in the District No. of the Panchayat Constituencies panch constituencies Halqa Samba 1 Bari P.H. 1 Badhori P.C. I Moh. Masha Majla, Mela Moh. Masha Majla, Mela Brahmana P.C.II Moh. Cheer, Tharkhana, Moh. Cheer, Tharkhana, ramdassia & Moh Cheer ramdassia & Moh Cheer Khad Khad P.C.III Moh. Jasrotia, Moh. Moh. Jasrotia, Moh. Salara Salara Upper & Moh Upper & Moh Sarpanch Sarpanch P.C.IV Moh Salara Lower, Moh. Moh Salara Lower, Moh. Dina Nath & Moh Hakla Dina Nath & Moh Hakla P.C.V Moh. Tapyal Moh. Tapyal P.C.VI Moh. Chichian Moh. Chichian P.C.VII Moh. Chigal, Karki, Moh Moh. Chigal, Karki, Moh Bizard & Moh. Bizard & Moh. Masha/Ramdassia Masha/Ramdassia P.C.VIII Moh. Dera Moh. Dera P.C.IX Moh. ST & Moh. OBC Moh. ST & Moh. OBC Page 1 of 58 District Name of Block Block Name Pyt No. Name Number & Name of Panch Area inlcuded in the District No. of the Panchayat Constituencies panch constituencies Halqa P.C. I Khiddia Khiddia P.C.II Moh. Masha & Moh. Baj Moh. Masha & Moh. Baj Singh Singh P.C.III Moh Khatana, Moh. Moh Khatana, Moh. Hakla , Hakla , Moh Masha & Moh Masha & Moh. Moh. Bhagata Bhagata P.C.IV Moh. Khepar. Bilal, Moh. Khepar. Bilal, Chichian Chichian P.C.V Moh. Chard Moh. Chard P.H. 2 Bari P.C.VI Moh. Maj. -

Social Science PULLOUT WORKSHEETS for CLASS IX Second Term

Based on CCE Solutions to Me ‘n’ Mine Social Science PULLOUT WORKSHEETS FOR CLASS IX Second Term By Niti Arora Kumkum Kumari B.A., Geog. Hons. B.Ed Delhi Public School Mathura Road, New Delhi New Saraswati House (India) Pvt. Ltd. EDUCATIONAL PUBLISHERS Second Floor, M.G.M. Tower, 19, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi-110002 Ph: 43556600 • Fax: 43556688 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.saraswatihouse.com Branches • Ahmedabad: (079) 22160722 • Bengaluru: (080) 26619880 • Chennai: (044) 24346531 • Dehradun: 09837452852 • Guwahati: (0361) 2457198 • Hyderabad: (040) 42615566 • Jaipur: (0141) 4006022 • Jalandhar: (0181) 4642600 • Kochi: (0484) 3925288 • Kolkata:(033) 22842222 • Lucknow: (0522) 4062517 • Mumbai: (022) 26874022 • Patna: (0612) 2570403 • Ranchi: (0651) 2210300 CONTENTS HISTORY Chapter Test .............................................................62-63 Forest Society and Colonialism Formative Assessment Worksheets 80 & 81 ...........................................63 Summative Assessment Worksheets 1 to 8 ............................................3-10 POLITICAL SCIENCE Chapter Test ..................................................................10 Electoral Politics Formative Assessment Summative Assessment Worksheets 9 & 10 .............................................11 Worksheets 82 to 88 ......................................64-69 Pastoralists in the Modern World Chapter Test .............................................................69-70 Summative Assessment Formative Assessment Worksheets 11 to -

Evolving Humanity, Emerging Worlds IUAES2013, University of Manchester, 5Th-10Th August 2013 Sponsors

The 17th World Congress of the IUAES2013 Evolving Humanity, Emerging Worlds Evolving Humanity, IUAES2013, University of Manchester, 5th-10th August 2013 Sponsors: Evolving Humanity, Emerging Worlds Monday 5th August, Bridgewater Hall (Monday only) 12.00-14.00 Registration 14.00-15.00 Opening Ceremony 15.00-16.30 Inaugural Lecture by Leslie Aiello 16.30-17.00 Coffe/Tea Break 17.00-19.00 Plenary Debate: “Humans have no nature, what they have is history” 19.00-21.00 Reception Tuesday 6th August, University Conference Centre Complex (all remaining days) 09.00-10.30 Panel Sessions 10.30-11.00 Coffee/Tea Break 11.00-12.30 Panel Sessions 12.30-14.00 Lunch (also ASA AOB meeting and ICSU presentation) 14.00-15.30 Panel Sessions 15.30-16.00 Coffee/Tea Break 16.00-17.30 Firth Lecture by Lourdes Arizpe 18.00-19.00 IUAES Commission Business Meetings and Other meetings 19.00-21.00 Presentation of bids to host future congesses and inter-congresses Wednesday 7th August 09.00-10.30 Panel Sessions 10.30-11.00 Coffee/Tea Break Hallsworth Plenary Debate: 11.00-13.00 “Justice for people must come before justice for the environment”. 13.00-14.30 Lunch (also ERCEA presentation, EASA Mobilities and AMCE meetings) 14.30-16.00 Panel Sessions 16.00-16.30 Coffee/Tea Break 16.30-18.00 Panel Sessions 18.30-19.30 WCAA Ethics Taskforce and WCAA IntDels meetings 19.30-21.00 Open Commissions Meeting Thursday 8th August 09.00-10.30 Panel Sessions 10.30-11.00 Coffee/Tea Break 11.00-12.30 Panel Sessions 12.30-14.00 Lunch (also ASA Apply meeting) 14.00-15.30 Panel Sessions 15.30-16.00 Coffee/Tea Break 16.00-17.30 Huxley Lecture by Howard Morphy 18.00-19.00 ALA, VANEASA and WCAA AOA meetings 19.00-21.00 Council of IUAES Commissions Friday 9th August 09.00-10.30 Panel Sessions 10.30-11.00 Coffee/Tea Break Plenary Debate: 11.00-13.00 “The free movement of people around the world would be utopian”.