1 Samnites, Ligurians and Romans Revisited John R. Patterson This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONSIDERAZIONI Di Storia Ed Archeologia 2021

CONSIDERAZIONI di Storia ed Archeologia 2021 CONSIDERAZIONI DI STORIA ED ARCHEOLOGIA DIRETTORE GIANFRANCO DE BENEDITTIS Comitato di redazione Rosalba ANTONINI Paolo MAURIELLO Maria Assunta CUOZZO Antonella MINELLI Cecilia RICCI Gianluca SORICELLI Comitato Scientifico BARKER Graeme CAMBRIDGE, BISPHAM Edward OXFORD, CAPPELLETTI Loredana VIENNA. CORBIER Cecilia PARIGI , CROWFORD Michael LONDRA, D’ERCOLE Cecilia PARIGI, ESPINOSA David OVIEDO, ISAYEV Elena EXETER, LETTA Cesare PISA, OAKLEY Stephen CAMBRIDGE, PELGROM Jeremia GRONINGEN, STECK Tesse LEIDEN, TAGLIAMONTE Gianluca LECCE Segreteria Gino AMOROSA Marilena COZZOLINO Federico RUSSO Autorizzazione del Tribunale di Campobasso nr. 6/08 cr. n. 2502 del 17.09.2008 La rivista è scaricabile gratuitamente dal sito www.samnitium.com ISSN 2039-4845 (testo a stampa) ISSN 2039-4853 (testo on line) INDICE p. 3 CARTA ARCHEOLOGICA DEL MUNICIPIUM DEI LIGURES BAEBIANI (MACCHIA DI CIRCELLO, BN) Paola Guacci p. 34 ASPETTI LETTERARI DI UNA CONTROVERSA ISCRIZIONE (CIL IX 2689) Laura Fontana p. 48 NOTE SUI QUAESTORES ENTRO COLONIE LATINE Federico Russo p. 57 PER UN DOSSIER SULLA LINGUA SANNITICA DI TEANUM APULUM Gianfranco De Benedittis p. 72 FRUSTULA BARANELLENSIA 2 TESSERAE IN TERRACOTTA DAL MUSEO CIVICO “GIUSEPPE BARONE” Jessica Piccinini p. 83 FORTIFICAZIONI MEGALITICHE NEL VALLO DI DIANO CUOZZO DELLA CIVITA - TEGGIANUM LUCANA E LE SUE FORTIFICAZIONI SATELLITI DI CUOZZO DELL’UOVO E DI CIMA 760 SAGGIO DI FOTOINTERPRETAZIONE ARCHEOLOGICA Domenico Caiazza NOTE SUI QUAESTORES ENTRO COLONIE LATINE Federico Russo 1. I quaestores locali Alcune fra le più antiche testimonianze epigrafiche restituiteci dalla colonia latina di Paestum per- mettono di affrontare un problema di carattere storico-istituzionale da lungo tempo dibattuto in dot- trina, quello della funzione e del profilo giuridico dei quaestores locali dell’Italia antica, con particolare riferimento a quelli attestati nelle colonie latine. -

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N. Purcell, 1997 Introduction The landscape of central Italy has not been intrinsically stable. The steep slopes of the mountains have been deforested–several times in many cases–with consequent erosion; frane or avalanches remove large tracts of regolith, and doubly obliterate the archaeological record. In the valley-bottoms active streams have deposited and eroded successive layers of fill, sealing and destroying the evidence of settlement in many relatively favored niches. The more extensive lowlands have also seen substantial depositions of alluvial and colluvial material; the coasts have been exposed to erosion, aggradation and occasional tectonic deformation, or–spectacularly in the Bay of Naples– alternating collapse and re-elevation (“bradyseism”) at a staggeringly rapid pace. Earthquakes everywhere have accelerated the rate of change; vulcanicity in Campania has several times transformed substantial tracts of landscape beyond recognition–and reconstruction (thus no attempt is made here to re-create the contours of any of the sometimes very different forerunners of today’s Mt. Vesuvius). To this instability must be added the effect of intensive and continuous intervention by humanity. Episodes of depopulation in the Italian peninsula have arguably been neither prolonged nor pronounced within the timespan of the map and beyond. Even so, over the centuries the settlement pattern has been more than usually mutable, which has tended to obscure or damage the archaeological record. More archaeological evidence has emerged as modern urbanization spreads; but even more has been destroyed. What is available to the historical cartographer varies in quality from area to area in surprising ways. -

Relazione Tecnica

VERIFICA PREVENTIVA DI INTERESSE ARCHEOLOGICO PROGETTO PER LA REALIZZAZIONE DI UN IMPIANTO IDROELETTRICO DI REGOLAZIONE SUL BACINO DI CAMPOLATTARO COMMITTENTE: REC S.R.L VIA GIULIO UBERTI 37 MILANO ANALISI ARCHEOLOGICA – RELAZIONE TECNICA COORDINAMENTO ATTIVITÀ: APOIKIA S.R.L. – SOCIETÀ DI SERVIZI PER L’ARCHEOLOGIA CORSO VITTORIO EMANUELE 84 NAPOLI 80121 TEL. 0817901207 P. I. 07467270638 [email protected] DATA GIUGNO 2012 CONSULENZA ARCHEOLOGICA: RESPONSABILE GRUPPO DI LAVORO: DOTT.SSA FRANCESCA FRATTA DOTT.SSA AURORA LUPIA COLLABORATORI: DOTT. ANTONIO ABATE DOTT.SSA BIANCA CAVALLARO DOTT. GIANLUCA D’AVINO DOTT.SSA CONCETTA FILODEMO DOTT. NICOLA MELUZIIS DOTT. SSA RAFFAELLA PAPPALARDO DOTT. FRANCESCO PERUGINO DOTT..SSA MARIANGELA PISTILLO REC- iIMPIANTO IDROELETTRICO DI REGOLAZIONE SUL BACINO DI CAMPOLATTARO Relazione Tecnica PREMESSA 1. METODOLOGIA E PROCEDIMENTO TECNICO PP. 4-26 1.1 LA SCHEDATURA DEI SITI DA BIBLIOGRAFIA E D’ARCHIVIO PP. 4-6 1.2 LA FOTOINTERPRETAZIONE PP. 7-9 1.3 LA RICOGNIZIONE DI SUPERFICIE PP. 10-20 1.4 APPARATO CARTOGRAFOICO PP. 21-26 2. INQUADRAMENTO STORICO ARCHEOLOGICO PP. 27-53 3. L'ANALISI AEROTOPOGRAFICA PP. 54-58 4. LA RICOGNIZIONE DI SUPERFICIE - SURVEY PP. 59-61 5. CONCLUSIONI PP. 62-84 BIBLIOGRAFIA PP. 84-89 ALLEGATI SCHEDOGRAFICI: LE SCHEDE DELLE EVIDENZE DA BIBLIOGRAFIA LE SCHEDE DELLE TRACCE DA FOTOINTERPRETAZIONE LE SCHEDE DI RICOGNIZIONE: - SCHEDE UR - SCHEDE UDS - SCHEDE SITI - SCHEDE QUANTITATIVE DI MATERIALI ARCHEOLOGICI - DOCUMENTAZIONE FOTOGRAFICA SITI E REPERTI ARCHEOLOGICI UDS ALLEGATI CARTOGRAFICI: -

Tituli Honorarii, Monumentale Eregedenktekens. Ere-Inscripties Ten Tijde Van Het Principaat Op Het Italisch Schiereiland

Annelies De Bondt 2e licentie Geschiedenis Optie Oude Geschiedenis Stnr. 20030375 Faculteit van de Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Vakgroep Oude Geschiedenis van Europa Blandijnberg 2 9000 Gent Tituli honorarii, monumentale eregedenktekens. Ere-inscripties ten tijde van het Principaat op het Italisch schiereiland. Een statistisch-epigrafisch onderzoek. Fascis 3: Inventaris. Promotor: Prof. Dr. Robert DUTHOY Licentiaatsverhandeling voorgedragen tot Leescommissarissen: Prof. Dr. Dorothy PIKHAUS het behalen van de graad van A Dr. Koenraad VERBOVEN Licentiaat/Master in de geschiedenis. Inventaris 0. Inhoudsopgave 0. Inhoudsopgave 1 1. Inleiding 5 1.1. Verantwoording nummering 5 1.2. Diakritische tekens 6 1.3. Bibliografie en gebruikte afkortingen. 6 2. Inventaris 9 Regio I, Latium et Campania 9 Latium Adjectum 9 Aletrium 9 Fundi 17 Anagnia 9 Interamna Lirenas 18 Antium 10 Minturnae 19 Aquinum 11 Privernum 20 Ardea 11 Rocca d’Arce 20 Atina 12 Setia 21 Casinum 12 Signia 21 Cereatae Marianae 13 Sinuessa 21 Circeii 13 Suessa Aurunca 21 Cora 13 Sura 23 Fabrateria Vetus 14 Tarracina 23 Ferentinum 15 Velitrae 23 Formiae 16 Verulae 23 Latium Vetus 24 Albanum 24 Lavinium 28 Bovillae 24 Ostia Antica 30 Castel di Decima 25 Portus 37 Castrimoenium 25 Praeneste 37 Gabiae 26 Tibur 39 Labico 27 Tusculum 42 Lanuvium 27 Zagarollo 43 Campania 44 Abella 44 Neapolis 56 Abellinum 44 Nola 56 Acerrae 45 Nuceria 57 Afilae 45 Pompei 57 Allifae 45 Puteoli 58 Caiatia 46 Salernum 62 Cales 47 Stabiae 63 Capua 48 Suessula 63 Cubulteria 50 Surrentum 64 Cumae 50 Teanum Sidicinum -

Politics and Policy: Rome and Liguria, 200-172 B.C

Politics and policy: Rome and Liguria, 200-172 B.C. Eric Brousseau, Department of History McGill University, Montreal June, 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. ©Eric Brousseau 2010 i Abstract Stephen Dyson’s The Creation of the Roman Frontier employs various anthropological models to explain the development of Rome’s republican frontiers. His treatment of the Ligurian frontier in the second century BC posits a Ligurian ‘policy’ crafted largely by the Senate and Roman ‘frontier tacticians’ (i.e. consuls). Dyson consciously avoids incorporating the pressures of domestic politics and the dynamics of aristocratic competition. But his insistence that these factors obscure policy continuities is incorrect. Politics determined policy. This thesis deals with the Ligurian frontier from 200 to 172 BC, years in which Roman involvement in the region was most intense. It shows that individual magistrates controlled policy to a much greater extent than Dyson and other scholars have allowed. The interplay between the competing forces of aristocratic competition and Senatorial consensus best explains the continuities and shifts in regional policy. Abstrait The Creation of the Roman Frontier, l’œuvre de Stephen Dyson, utilise plusieurs modèles anthropologiques pour illuminer le développement de la frontière républicaine. Son traitement de la frontière Ligurienne durant la deuxième siècle avant J.-C. postule une ‘politique’ envers les Liguriennes déterminer par le Sénat et les ‘tacticiens de la frontière romain’ (les consuls). Dyson fais exprès de ne pas tenir compte des forces de la politique domestique et la compétition aristocratique. Mais son insistance que ces forces cachent les continuités de la politique Ligurienne est incorrecte. -

I LIGURI APUANI Storiografia, Archeologia, Antropologia E Linguistica

I LIGURI APUANI storiografia, archeologia, antropologia e linguistica di Lanfranco Sanna I Liguri Prima di affrontare la storia dei liguri apuani è bene fare alcuni riferimenti sull' etnogenesi dei Liguri. Quando compare per la prima volta il nome «ligure» nella storia? Αιθιοπας τε Λιγυς τε ιδε Σκυθας ιππηµολγους «E gli Etiopi e i Liguri e gli Sciti mungitori di cavalle» L’esametro, citato da Eratostene di Cirene e da lui attribuito a Esiodo, conserva la più antica memoria dei Liguri giunta fino a noi (VIII-VII sec. a.C.). I Liguri, secondo i Greci, erano gli abitanti dell’Occidente. Esiodo L’aggettivo «ligure» ha un carattere letterario e linguistico allogeno, perché si deve totalmente inquadrare nell’evoluzione della fonetica greco-latina Ligues > Ligures. Anche oggi nessun dialetto ligure possiede il termine dialettale per definire se stesso tale, né un abitante delle regioni vicine chiamerà mai “liguri” gli abitanti della Liguria. Ma da dove deriva questo nome? All’inizio «Liguri» avrebbe significato «abitanti della pianura alluvionale del Rodano». I contatti dei navigatori e poi dei coloni greci proprio con le tribù liguri del delta del Rodano spiegherebbero la sua estensione a tutto ethnos. Sinteticamente l’origine e l’evoluzione del nome dei Liguri avrebbe seguito questo percorso: - 700 a. C.: i primi navigatori greci prendono contatti commerciali con gli Elysici di Narbona. Gli abitanti scendono nella pianura sottostante la rocca assumendo il nome di Ligues derivato dal sustrato indigeno e attribuito loro dai Greci. - 600 a. C.: i Focesi fondano Massalia (Marsiglia) e per estensione chiamano Ligues le popolazioni indigene sia a est cha a ovest del Rodano. -

Piano Territoriale Di Coordinamento

PROVINCIA DI BENEVENTO REGION E CAMPANI A P IANO T ERRITORIALE DI C OORDINAMENTO DELLA PROVINCIA DI BENEVENTO art. 18 L.R. Campania 22.12.04, n.16 – L.R. Campania 13.10.2008, n.13 PARTE PROGRAMMATICA SEZIONE C Ottobre 2012 1 P T C P B N – P a r t e P r o g r a m m a t i c a PROVINCI A DI BENEVENT O REGION E CAMPANI A Prof . Ing . Aniell o Cimitile , Avv . Giovann i Angel o Mos è Bozzi , President e dell a Provinci a di Benevento . Assessor e all e Politich e pe r l’urbanistica . Dott . Claudio Uccelletti , President e dell a Sanni o Europ a SCp A 2 P T C P B N – P a r t e P r o g r a m m a t i c a PROVINCIA DI BENEVENTO PIAN O TERRITORIAL E DI COORDINAMENT O PROVINCIALE : Consulenz a scientifica : prof . arch . Alessandr o Dal Pia z Progetto : SANNI O EUROP A Scp A Are a Pianificazion e e Programmazion e Territoriale . Coordinamento : Giusepp e Iadarola , architetto . Dan a Vocino , architetto . Coordinament o operativo : Samanth a Calandrelli , architetto . Collaborazione : geom . Donat o Brillante , geom . Vittori o A. D’Onofrio , geom. Serena Marsullo, geom. Leonardo Lucarelli. STRUTTUR A TECNIC A DELL A PROVINCI A DI BENEVENTO : Grupp o di lavoro : dott . agr . Pasqual e Di Giambattist a (Responsabil e Servizi o Pian i e Programmi) , Coordinament o adeguament o PTCP ; arch . Michel e Orsill o (Servizi o Urbanistica) ; dott . agr . Antoni o Castellucc i (Settor e Attivit à Produttive , Svilupp o Attivit à Economich e e Agricoltura) ; ing . -

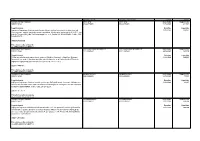

Lotto Operatori Invitati Operatori Aggiudicatari Tempi Importo

Lotto Operatori invitati Operatori aggiudicatari Tempi Importo Comune Di San Nazzaro MYO SPA MYO SPA Data inizio Aggiudicato 80001310624 03222970406 03222970406 16/12/2020 231,00€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato Impegno di spesa per fornitura carta formato A4 per ricarica fotocopiatrici in dotazione agli 31/12/2020 230,78€ uffici comunali, nonché materiale vario di cancelleria. Affidamento fornitura ditta MYO SRL con sede in Torriana (RN), alla Via Santarcangiolese, n. 6, Partita IVA: 03222970406, Codice CIG: Z652FCEDEE. CIGZ652FCEDEE Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Comune Di San Nazzaro PEPE GIOVANNI DOMENICO PEPE GIOVANNI DOMENICO Data inizio Aggiudicato 80001310624 01177360623 01177360623 22/12/2020 320,00€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato Servizi urgenti di manutenzione loculi-ossari nel Cimitero Comunale. Ditta Pepe Giovanni 31/12/2020 320,00€ Domenico, con sede in San Nazzaro (BN) alla Via Castello, n. 4, Partita IVA 01177360623. Impegno di spesa e liquidazione fattura. Codice CIG: Z112FEE0E6. CIGZ112FEE0E6 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Comune Di San Nazzaro MAGGIOLI SPA MAGGIOLI SPA Data inizio Aggiudicato 80001310624 02066400405 02066400405 23/12/2020 79,00€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato Impegno di spesa per fornitura manuale pratico per l'Ufficio Elettorale comunale. Affidamento 31/12/2020 86,20€ fornitura Società MAGGIOLI SpA con sede in Santarcangelo di Romagna in Via Del Carpino 8. Partita IVA 02066400405. Codice CIG: ZAF2FF2EC8. CIGZAF2FF2EC8 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Comune Di San Nazzaro ACHABMEDSRL ACHABMEDSRL Data inizio Aggiudicato 80001310624 01332290624 01332290624 24/12/2020 800,00€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato Impegno di spesa e affidamento fornitura calendari 2121 con personalizzazione grafica della 31/12/2020 800,00€ raccolta differenziata settimanale dei rifiuti comunali. -

Collegia Centonariorum: the Guilds of Textile Dealers in the Roman West

Collegia Centonariorum: Th e Guilds of Textile Dealers in the Roman West Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition Editorial Board William V. Harris (editor) Alan Cameron, Suzanne Said, Kathy H. Eden, Gareth D. Williams VOLUME 34 Collegia Centonariorum: Th e Guilds of Textile Dealers in the Roman West By Jinyu Liu LEIDEN • BOSTON 2009 Cover illustration: CIL V. 2864 = ILS 5406, in S. Panciera, 2003. “I numeri di Patavium.” EΡKOΣ. Studi in Onore di Franco Sartori. Padova, 2003: 187–208. Courtesy of Musei Civici di Padova. Th is book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Liu, Jinyu, 1972– Collegia centonariorum : the guilds of textile dealers in the Roman West / by Jinyu Liu. p. cm. — (Columbia studies in the classical tradition ; v. 34) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-17774-1 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Textile workers—Labor unions—Rome—History. 2. Textile industry—Rome— History. I. Title. II. Series. HD8039.T42R655 2009 381’.4567700937—dc22 2009029996 ISSN 0166-1302 ISBN 978 90 04 17774 1 Copyright 2009 by Th e Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to Th e Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Azienda Speciale Consortile B02 Ufficio Di Piano Via Giuseppe Mazzini N

AZIENDA SPECIALE CONSORTILE B02 UFFICIO DI PIANO VIA GIUSEPPE MAZZINI N. 13 82018 - SAN GIORGIO DEL SANNIO (BN) - C.F. 01752300622 Tel. e fax 0824/58214 e-mail [email protected] ; [email protected] Ai Servizi Sociali del Comune di _______________________________________ OGGETTO: RICHIESTA DI ACCESSO AL SERVIZIO DI ASSISTENZA DOMICILIARE SOCIO-ASSISTENZIALE PER ANZIANI E DISABILI. Il sottoscritto/a ____________________________________________________________________ Nato il ________________ a __________________________________________________________ Residente in ________________________________ Via______________________________ n° ___ C.F.|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___| Doc. di identità n° ______________ Rilasciato da _________________________________________ Tel./ Cellulare______________________________ Email/pec _______________________________ In qualità di: Destinatario del servizio; Tutore / Amministratore di sostegno – Sentenza n. ___________del ______________ Familiare (indicare grado) ________________________________________________ Del Sig./Sig.ra ___________________________________________________________________ Nato/a il _________________a ________________________________________________________ Residente in _______________________________Via ______________________________n°____ C.F.|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___| Azienda Speciale Consortile B02 Prot. in partenza n. 0004228 del 15-09-2020 Doc. di identità n° ______________ Rilasciato -

![An Atlas of Antient [I.E. Ancient] Geography](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8605/an-atlas-of-antient-i-e-ancient-geography-1938605.webp)

An Atlas of Antient [I.E. Ancient] Geography

'V»V\ 'X/'N^X^fX -V JV^V-V JV or A?/rfn!JyJ &EO&!AElcr K T \ ^JSlS LIBRARY OF WELLES LEY COLLEGE PRESENTED BY Ruth Campbell '27 V Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Boston Library Consortium Member Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/atlasofantientieOObutl AN ATLAS OP ANTIENT GEOGRAPHY BY SAMUEL BUTLER, D.D. AUTHOR OF MODERN AND ANTJENT GEOGRAPHY FOR THE USE OF SCHOOLS. STEREOTYPED BY J. HOWE. PHILADELPHIA: BLANQHARD AND LEA. 1851. G- PREFATORY NOTE INDEX OF DR. BUTLER'S ANTIENT ATLAS. It is to be observed in this Index, which is made for the sake of complete and easy refer- ence to the Maps, that the Latitude and Longitude of Rivers, and names of Countries, are given from the points where their names happen to be written in the Map, and not from any- remarkable point, such as their source or embouchure. The same River, Mountain, or City &c, occurs in different Maps, but is only mentioned once in the Index, except very large Rivers, the names of which are sometimes repeated in the Maps of the different countries to which they belong. The quantity of the places mentioned has been ascertained, as far as was in the Author's power, with great labor, by reference to the actual authorities, either Greek prose writers, (who often, by the help of a long vowel, a diphthong, or even an accent, afford a clue to this,) or to the Greek and Latin poets, without at all trusting to the attempts at marking the quantity in more recent works, experience having shown that they are extremely erroneous. -

TESTING the PERFORMANCE of BATS AS INDICATORS of HABITAT QUALITY in RIPARIAN ECOSYSTEMS Phd Candidate: Carmelina De Conno

UNIVESITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI FEDERICO II DOCTORAL SCHOOL OF AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SCIENCES (XXIX Cycle) TESTING THE PERFORMANCE OF BATS AS INDICATORS OF HABITAT QUALITY IN RIPARIAN ECOSYSTEMS PhD candidate: Carmelina De Conno Tutor: Danilo Russo Coordinator: Guido D’Urso Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Doctoral School of Agriculture and Food Sciences (XXIX cycle) TESTING THE PERFORMANCE OF BATS AS INDICATOR OF HABITAT QUALITY IN RIPARIAN ECOSYSTEMS PhD candidate: Carmelina De Conno Tutor: Danilo Russo Co-tutor: Salvatore De Bonis Coordinator: Guido D’Urso February 2017 2 3 AKNOWLEDGEMENTS I really have to thank all the beautiful people who helped me in this long journey called PhD. First of all, my tutor, Danilo Russo, who is showing me the amazing world of scientific research and Valentina Nardone, without whom this work would probably not have been carried out. Then I want to thank Ugo Scarpa, Iñes Jorge and Olivier Bastianelli, who were fundamental for the field work, Leonardo Ancillotto for statistics and Maria Monteverde, Ivano Nicolella and Maria Raimondo for their help. I am grateful to the Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park and to the WWF oasis “Gole del Sagittario”, “Persano”, “Lago di Serranella”, “Cascate del Rio Verde”, “Lago di Campolattaro” and “Pianeta Terra Onlus” association for hosting us. Thanks also go to Phillip Spellman, who kindly revised the English and to all the Wildlife Research Unit (WRU) members for welcoming me in their group. Last but not least, I thank my family and Francesco for always loving, supporting and bearing me. 4 INDEX 1. Introduction 6 1.1.