602KB***Composition – Legal and Theoretical Foundations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incest Statutes

Statutory Compilation Regarding Incest Statutes March 2013 Scope This document is a comprehensive compilation of incest statutes from U.S. state, territorial, and the federal jurisdictions. It is up-to-date as of March 2013. For further assistance, consult the National District Attorneys Association’s National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse at 703.549.9222, or via the free online prosecution assistance service http://www.ndaa.org/ta_form.php. *The statutes in this compilation are current as of March 2013. Please be advised that these statutes are subject to change in forthcoming legislation and Shepardizing is recommended. 1 National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse National District Attorneys Association Table of Contents ALABAMA .................................................................................................................................................................. 8 ALA. CODE § 13A-13-3 (2013). INCEST .................................................................................................................... 8 ALA. CODE § 30-1-3 (2013). LEGITIMACY OF ISSUE OF INCESTUOUS MARRIAGES ...................................................... 8 ALASKA ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 ALASKA STAT. § 11.41.450 (2013). INCEST .............................................................................................................. 8 ALASKA R. EVID. RULE 505 (2013) -

Nebraska Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS)

Nebraska Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) Manual for Automated Agencies November, 2000 Nebraska Commission on Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice 301 Centennial Mall South, P.O. Box 94946 Lincoln, Nebraska 68509-4946 (402) 471-2194 TABLE OF CONTENTS NEBRASKA INCIDENT-BASED REPORTING SYSTEM (NIBRS) ........................ 1 Definition of "Incident” ...................................................... 4 DATA REQUIREMENTS .......................................................... 7 Requirements for each Group A Offense ......................................... 8 Requirements for Arrests for Group A and Group B Offenses ......................... 15 DEFINITIONS OF BASIC CORE, ADDITIONAL DATA ELEMENT AND ARRESTEE ELEMENTS Age .................................................................... 17 Aggravated Assault / Homicide Circumstances .................................... 17 Armed With . 18 Arrest Date . 19 Arrest (Transaction) Number ................................................. 19 Arrest Offense Code ........................................................ 19 Attempted / Completed ..................................................... 19 Criminal Activity Type ..................................................... 20 Date Recovered ........................................................... 20 Disposition of Arrestee Under Age 18 .......................................... 20 Drug Type / Type Criminal Activity (Arrestee) ................................... 21 Estimated Drug Quantity / Type Drug Measurement .............................. -

Misprison of Felony

South Carolina Law Review Volume 6 Issue 1 Article 8 Fall 9-1-1953 Misprison of Felony E. L. Morgan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation E. Lee Morgan, Misprison of Felony, 6 S.C.L.R. 87. (1953). This Note is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Morgan: Misprison of Felony MISPRISION OF FELONY Misprision1 of felony has been defined in various ways, but per- haps its best definition is as follows: "Misprision of felony at common law is a criminal neglect either to prevent a felony from being committed or to bring the offender to justice after its com- mission, but without such previous concert with or subsequent assis- tance of him as will make the concealer an accessory before or after 12 the fact." In the modern use of the term, misprision of felony has been said to be almost, if not identically, the same offense as that of an acces- sory after the fact.3 It has also been stated that misprision is nothing more than a word used to describe a misdemeanor which does not possess a specific name.4 It is that offense of concealing a felony committed by another, but without such previous concert with or subsequent assistance to the felon as would make the concealing party an accessory before or after the fact.5 Misprision is distinguished from compounding an offense on the basis of consideration or amends; misprision is a bare concealment of crime, while compounding is a concealment for a reward by one 6 directly injured by the crime. -

1 PUBLIC JUSTICE OFFENCES Hindering Investigations

PUBLIC JUSTICE OFFENCES Hindering investigations; concealing offences and attempting to pervert the course of justice Reasonable Cause Criminal Law CLE Conference 28 March 2015 Part 7 of the Crimes Act 1900 was introduced as a package of Public Justice Offences inserted into the Crimes Act in 1990.1 The purpose of the package was to create a comprehensive statement of the law relating to public justice offences which, until the enactment of the amendments, was described by the then Attorney General Mr John Dowd as “fragmented and confusing, consisting of various common law and statutory provisions, with many gaps, anomalies and uncertainties”.2 Part 7 Division 2 deals broadly with offences concerning the interference in the administration of justice. This paper does not aim to cover every aspect of the package of public justice offences but focuses on the principal offences incorporated within Division 2, being Ss. 315, 316 and 319 offences, and their common law equivalents. Background Up until 25 November 1990, the various common law offences including misprision of felony, hindering an investigation, compounding a felony and perverting the course of justice, to name a few, operated, until abolished by the Crimes (Public Justice) Amendment Act 19903. From 25 November 1990, Part 7 of the Crimes Act 1900 provided for ‘public justice offences’ broadly described as offences targeting interference with the administration 1 Inserted by the Crimes (Public Justice) Amendment Act 1990 (NSW) s 3, Sch 1. 2 New South Wales, Parliamentary Debates (Hansard) Legislative Assembly, 17 May 1990, the Hon JRA Dowd, Attorney General, Second Reading Speech at 3692. -

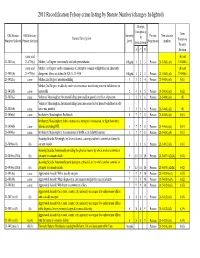

2011 Recodification Felony Crime Listing by Statute Number (Changes Hi-Lighted)

2011 Recodification Felony crime listing by Statute Number (changes hi-lighted) Attempt, Conspiracy, Old Statute Old Statutory Severity Person New statute New Statute Description & Number Violated Penalty Section Level Nonperson number Statutory Solicitation Penalty A C S Section same and (b) and 21-3401(a) 21-4706(c) Murder; 1st Degree; intentionally and with premeditation Off-grid 1 2 3 Person 21-5402(a)(1) 21-6806(c) same and Murder; 1st Degree; in the commission of, attempt to commit, or flight from an inherently (b) and 21-3401(b) 21-4706(c) dangerous felony as defined in K.S.A. 21-3436 Off-grid 1 2 3 Person 21-5402(a)(2) 21-6806(c) 21-3402(a) same Murder; 2nd Degree; intentional killing 1 3 3 4 Person 21-5403(a)(1) (b)(1) Murder; 2nd Degree; recklessly, under circumstances manifesting extreme indifference to 21-3402(b) same human life 2 4 4 5 Person 21-5403(a)(2) (b)(2) 21-3403(a) same Voluntary Manslaughter; Intentional killing upon sudden quarrel or in heat of passion 3 5 5 6 Person 21-5404(a)(1) (b) Voluntary Manslaughter; Intentional killing upon unreasonable but honest belief that deadly 21-3403(b) same force was justified 3 5 5 6 Person 21-5404(a)(2) (b) 21-3404(a) same Involuntary Manslaughter; Recklessly 5 7 7 8 Person 21-5405(a)(1) (b)(1) Involuntary Manslaughter; In the commission, attempted commission, or flight from other 21-3404(b) same felonies excluding DUI 5 7 7 8 Person 21-5405(a)(2) (b)(1) 21-3404(c) same Involuntary Manslaughter; In commission of lawful act in unlawful manner 5 7 7 8 Person 21-5405(a)(4) (b)(1) -

National Incident-Based Reporting System Volume 1: Data Collection Guidelines

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Criminal Justice Information Services Division Uniform Crime Reporting National Incident-Based Reporting System Volume 1: Data Collection Guidelines August 2000 NATIONAL INCIDENT-BASED REPORTING SYSTEM VOLUME 1: DATA COLLECTION GUIDELINES Prepared by U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Criminal Justice Information Services Division Uniform Crime Reporting Program August 2000 FOREWORD Information about the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) is contained in the four documents described below: Volume 1: Data Collection Guidelines This document is for the use of local, state, and federal Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program personnel (i.e., administrators, training instructors, report analysts, coders, data entry clerks, etc.) who are responsible for collecting and recording NIBRS crime data for submission to the FBI. It contains a system overview and descriptions of the offenses, offense codes, reports, data elements, and data values used in the system. Volume 2: Data Submission Specifications This document is for the use of local, state, and federal systems personnel (i.e., computer programmers, analysts, etc.) who are responsible for preparing magnetic media for submission to the FBI. It contains the data submission instructions for magnetic media, record layouts, and error-handling procedures that must be followed in submitting magnetic media to the FBI for NIBRS reporting purposes. Volume 3: Approaches to Implementing an Incident-Based Reporting (IBR) System This document is for the use of local, state, and federal systems personnel (i.e., computer programmers, analysts, etc.) who are responsible for developing an IBR system that will meet NIBRS’s reporting requirements. -

Criminal Law

The Law Commission Working Paper No 62 Criminal Law Offences relating to the Administration of Justice LONDON HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 0 Crown copyright 7975 First published 7975 ISBN 0 11 730093 4 17-2 6-2 6 THE LAW COMMISSXON WORKING PAPER NO. 62 CRIMINAL LAW OFFENCES RELATING TO THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE CONTENTS Paras. I INTRODUCTION 1- 7 1 I1 PRESENT LAW 8- 25 5 Common Law 8- 17 5 Perverting the course of justice 8- 11 5 Examples of conspiracy charges 12- 13 8 Contempt of Court 14- 15 10 Escape and avoiding trial 16 11 Agreeing to indemnify bail 17 11 Statute ~aw 19- 25 12 Perjury 19- 20 12 Other statutory offences 21- 24 13 Summary 25 15 I11 PROPOSALS FOR REFORM 26-116 16 General 26- 33 16 Relationship with contempt of court 27- 29 17 Criminal and civil proceedings 30- 33 18 Outline of proposed offences 34- 37 20 1. Offences relating to all proceedings 38- 88 21 (i) Perjury 38- 60 21 iii Paras. Page Ihtroductory 38- 45 21 Should perjury be confined to false statements? 46 24 Oral evidence not on oath 47- 53 25 Extra-curial unsworn statements admissible as evidence 51- 59 28 Summary 60 31 (ii) Tampering with or fabricating evidence 61- 65 32 (iii)Preventing the attendance of witnesses 66- 67 34 (iv) Intimidation of a party 68- 84 35 (v) Improperly influencing a court 85- 91 43 2. Offences relating only to criminal matters 92-107 45 (i) Impeding the investigation of crime 93-101 45 (ii) Avoiding trial 102-105 50 (iii)Agreeing to indemnify bail 106-110 52 3. -

Parties to Crime Rollin M

March, i941 PARTIES TO CRIME ROLLIN M. PERKINS t I. TERMINOLOGY In the field of felony the common law divided guilty parties into principals and accessories.1 According to the ancient analysis only the actual perpetrator of the felonious deed was a principal. Other guilty parties were called "accessories", and to distinguish among these with reference to time and place they were divided into three classes: (I) accessories before the fact, (2) accessories at the fact,2 and (3) acces- sories after the fact. At a relatively early time the party who was originally considered an accessory at the fact, ceased to be classed in the accessorial group and was labeled a principal. To distinguish him from the actual perpetrator of the crime he was called a principal in the second degree. 3 Thereafter, in felony cases there were two kinds of principals, first degree and second degree, and two kinds of accessories, before the fact and after the fact. As applied to homicide cases, the common law of parties was summarized in this form by the Supreme Court of North Carolina: "The parties to a homicide are: (I) principals in the first degree, being those whose unlawful acts or omissions cause the death of the victim, without the intervention of any responsible agent; (2) principals in the second degree, being those who are actually or constructively present at the scene of the crime, aiding and abetting therein, but not directly causing the death; (3)acces- sories before the fact, being those who have conspired with the actual perpetrator to commit the homicide, or some other unlawful act that would naturally result in a homicide, or who have pro- cured, instigated, encouraged, or advised him to commit it, but who were neither actually nor constructively present when it was committed; and (4) accessories after the fact, being those who, t-A.B., I9IO, University of Kansas; J.D., 1912, Stanford University; S.J.D., 191i6, Harvard University; Professor of Law, State University of Iowa; author, Iowa Criminal Justice (1932), Cases on Criminal Procedure (3d ed. -

Criminal Code Recodification for North Carolinai the Problem

Criminal Code Recodification for North Carolinai The Problem North Carolina’s lack of a streamlined, comprehensive, orderly, and principled criminal code creates costly inefficiencies in the criminal justice system, opportunities for unfairness, and undermines the effectiveness of the criminal law. Although many of the state’s crimes are codified in Chapter 14 of the General Statutes (entitled “Criminal Law”), criminal offenses are peppered throughout the General Statutes. Felony offenses are found in fifty-three separate Chapters of the General Statutes.1 Misdemeanors are spread throughout one hundred and forty-two Chapters.2 Additionally, the law delegates to administrative bodies and boards the authority to proscribe crimes. For example, provisions in the General Statutes make it a misdemeanor to violate any rule or regulation promulgated by the Board of Agriculture concerning the marketing and branding of farm products or any regulation promulgated by the Board of Dental Examiners.3 Thus, “a dentist who runs an advertisement but neglects to include a statement regarding whether he or she is a general dentist or a specialist is a criminal, as is one who permits a dental hygienist to engage in the ‘[i]ntraoral use of a high speed handpiece.’"4 Counties, cities, towns, and metropolitan sewerage districts also have the authority to create crimes though local ordinances.5 Thus, because a local ordinance of Ahoskie, NC makes it unlawful for a person to allow “chickens and other domestic fowl . to be at large in the town,”6 such conduct constitutes a misdemeanor in that jurisdiction. Given that no central statewide database exists collecting all crimes created by administrative bodies, boards, and local government units, it is impossible to state how many crimes exist at any given time in North Carolina. -

Criminal Law

The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 96) CRIMINAL LAW OFFENCES RELATING TO INTERFERENCE WITH THE COURSE OF JUSTICE Laid before Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to heprinted 7th November 1979 LONDON HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE 213 24.50 net k The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are- The Honourable Mr. Justice Kerr, Chairman. Mr. Stephen M. Cretney. Mr. Stephen Edell. Mr. W. A. B. Forbes, Q.C. Dr. Peter M. North. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr. J. C. R. Fieldsend and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London, WClN 2BQ. 11 THE LAW COMMISSION CRIMINAL LAW CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION .......... 1.1-1.9 1 PART 11: PERJURY A . PRESENT LAW AND WORKING PAPER PROPOSALS ............. 2.1-2.7 4 1. Thelaw .............. 2.1-2.3 4 2 . The incidence of offences under the Perjury Act 1911 .............. 2.4-2.5 5 3. Working paper proposals ........ 2.6-2.7 7 B . RECOMMENDATIONS AS TO PERJURY IN JUDICIAL PROCEEDINGS ........ 2.8-2.93 8 1. The problem of false evidence not given on oath and the meaning of “judicial proceedings” ............ 2.8-2.43 8 (a) Working paperproposals ...... 2.9-2.10 8 (b) The present law .......... 2.1 1-2.25 10 (i) The Evidence Act 1851. section 16 2.12-2.16 10 (ii) Express statutory powers of tribunals ......... -

(PUBLIC JUSTICE) AMENDMENT ACT 1990 No. 51

CRIMES (PUBLIC JUSTICE) AMENDMENT ACT 1990 No. 51 NEW SOUTH WALES TABLE OF PROVISIONS 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Amendment of Crimes Act 1900 No. 40 4. Consequential amendment of other Acts SCHEDULE 1 - AMENDMENT OF CRIMES ACT 1900 SCHEDULE 2 - CONSEQUENTIAL AMENDMENT OFOTHER ACTS CRIMES (PUBLIC JUSTICE) AMENDMENT ACT 1990 No. 51 NEW SOUTH WALES Act No. 51, 1990 An Act to amend the Crimes Act 1900 to make further provision with respect to public justice offences; and for other purposes. [Assented to 18 September 1990] Crimes (Public Justice) Amendment 1990 The Legislature of New South Wales enacts: Short title 1. This Act may be cited as the Crimes (Public Justice) Amendment Act 1990. Commencement 2. This Act commences on a day or days to be appointed by proclamation. Amendment of Crimes Act 1900 No. 40 3. The Crimes Act 1900 is amended as set out in Schedule 1. Consequential amendment of other Acts 4. Each Act specified in Schedule 2 is amended as set out in that Schedule. SCHEDULE l - AMENDMENT OF CRIMES ACT 1900 (Sec. 3) (1) Section 1 (Short title and contents of Act): Omit the matter relating to Parts 7 and 8, insert instead: PART 7 - PUBLIC JUSTICE OFFENCES: CHAPTER 1 - Definitions - ss. 311-313 CHAPTER 2 - Interference with the administration of justice - ss. 314-319 CHAPTER 3 - Interference with judicial officers, witnesses, jurors etc. - ss. 320-326 CHAPTER 4 - Perjury, false statements etc. - ss. 324-339 CHAPTER 5 - Miscellaneous - ss. 340-343A. (2) Parts 7 and 8: Omit the Parts, insert instead: 2 Crimes (Public Justice) Amendment 1990 SCHEDULE 1 - AMENDMENT OF CRIMES ACT 1900 - continued PART 7 - PUBLIC JUSTICE OFFENCES CHAPTER 1 - Definitions Definitions 311. -

4140 Compounding Or Concealing a Felony

Page 1 Instruction 4.140 2009 Edition COMPOUNDING OR CONCEALING A FELONY COMPOUNDING OR CONCEALING A FELONY The defendant is charged with having violated section 36 of chapter 268 of our General Laws, which provides that: “Whoever, having knowledge of the commission of a felony, takes money, or a gratuity or reward, or an engagement therefor, upon an agreement or understanding, express or implied, to compound or conceal such felony, or not to prosecute therefor, or not to give evidence thereof shall . be punished . .” In order to prove that the defendant is guilty of this offense, the Commonwealth must prove three things beyond a reasonable doubt: First: That the defendant knew that a felony had been committed; Second: That the defendant made an agreement, either expressly or by a silent understanding, either to conceal that felony, or not to prosecute it, or not to give evidence about it; and Third: That the defendant made such an agreement in exchange for Instruction 4.140 Page 2 COMPOUNDING OR CONCEALING A FELONY 2009 Edition something of value or a promise of something of value. The essence of this offense is taking or agreeing to take money or something else of value in return for not prosecuting or giving evidence of a felony. In this Commonwealth, offenses that are punishable by imprisonment in the state prison are called “felonies”; lesser offenses are called “misdemeanors.” I instruct you as a matter of law that [alleged felony] is a felony. See, e.g., Commonwealth v. Pease, 16 Mass. 91 (1819) (acceptance of promissory note not to prosecute constitutes compounding a felony); Chester Glass Co.