Parties to Crime Rollin M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Statutes Minnesota 1913

GENERAL STATUTES OF MINNESOTA 1913 PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE LEGISLATURE BY VIRTUE OF AN ACT APPROVED APRIL 20, 1911 (LAWS 19,11, CH.299) COMPILED AND EDITED BY FRANCIS B. TIFFANY ST. PAUL WEST PUBLISHING CO. 0 1913 MINNESOTA STATUTES 1913 1890 EIGHTS OF ACCUSED § 8515 8515. Acquittal on part of charge—Whenever any person indicted for fel ony is acquitted by verdict of part of the offence charged and convicted pn the residue, such verdict may be received and recorded by the court, and thereupon he shall be adjudged guilty of the offence, if any, which appears to be substantially charged by the residue of the indictment, and sentenced ac cordingly. (4791)- 8516. Acquittal—When a bar—Whenever a defendant shall be acquitted or convicted upon an indictment for a crime consisting of different degrees, he cannot thereafter be indicted or tried for the same crime in any other de gree, nor for an attempt to commit the crime so charged, or any degree there of. (4792) See note to Const, art. 1 § 7. CHAPTER 95 CRIMES AGAINST THE SOVEREIGNTY OF THE STATE 8517. Treason—Every person who shall commit treason against the state shall be punished by imprisonment in the state prison for life. (4793) Petit treason does not exist in this state (3-246, 169). 8518. Misprision of treason—Every person having knowledge of the com mission of treason, who conceals the same, and does not, as soon as may be, disclose.such treason to the governor or a judge of the supreme or a district court, shall be guilty of misprision of treason, and punished by a fine not ex ceeding one thousand dollars, or by imprisonment in the state prison not ex ceeding five years, or in a common jail not exceeding two years. -

Mandatory Minimum Penalties and Statutory Relief Mechanisms

Chapter 2 HISTORY OF MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES AND STATUTORY RELIEF MECHANISMS A. INTRODUCTION This chapter provides a detailed historical account of the development and evolution of federal mandatory minimum penalties. It then describes the development of the two statutory mechanisms for obtaining relief from mandatory minimum penalties. B. MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES IN THE EARLY REPUBLIC Congress has used mandatory minimum penalties since it enacted the first federal penal laws in the late 18th century. Mandatory minimum penalties have always been prescribed for a core set of serious offenses, such as murder and treason, and also have been enacted to address immediate problems and exigencies. The Constitution authorizes Congress to establish criminal offenses and to set the punishments for those offenses,17 but there were no federal crimes when the First Congress convened in New York in March 1789.18 Congress created the first comprehensive series of federal offenses with the passage of the 1790 Crimes Act, which specified 23 federal crimes.19 Seven of the offenses in the 1790 Crimes Act carried a mandatory death penalty: treason, murder, three offenses relating to piracy, forgery of a public security of the United States, and the rescue of a person convicted of a capital crime.20 One of the piracy offenses specified four different forms of criminal conduct, arguably increasing to 10 the number of offenses carrying a mandatory minimum penalty.21 Treason, 17 See U.S. Const. art. I, §8 (enumerating powers to “provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting the Securities and current Coin of the United States” and to “define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offences against the Law of Nations”); U.S. -

Incest Statutes

Statutory Compilation Regarding Incest Statutes March 2013 Scope This document is a comprehensive compilation of incest statutes from U.S. state, territorial, and the federal jurisdictions. It is up-to-date as of March 2013. For further assistance, consult the National District Attorneys Association’s National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse at 703.549.9222, or via the free online prosecution assistance service http://www.ndaa.org/ta_form.php. *The statutes in this compilation are current as of March 2013. Please be advised that these statutes are subject to change in forthcoming legislation and Shepardizing is recommended. 1 National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse National District Attorneys Association Table of Contents ALABAMA .................................................................................................................................................................. 8 ALA. CODE § 13A-13-3 (2013). INCEST .................................................................................................................... 8 ALA. CODE § 30-1-3 (2013). LEGITIMACY OF ISSUE OF INCESTUOUS MARRIAGES ...................................................... 8 ALASKA ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 ALASKA STAT. § 11.41.450 (2013). INCEST .............................................................................................................. 8 ALASKA R. EVID. RULE 505 (2013) -

Federal Mandatory Minimum Sentencing Statutes

Federal Mandatory Minimum Sentencing Statutes Charles Doyle Senior Specialist in American Public Law September 9, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32040 Federal Mandatory Minimum Sentencing Statutes Summary Federal mandatory minimum sentencing statutes limit the discretion of a sentencing court to impose a sentence that does not include a term of imprisonment or the death penalty. They have a long history and come in several varieties: the not-less-than, the flat sentence, and piggyback versions. Federal courts may refrain from imposing an otherwise required statutory mandatory minimum sentence when requested by the prosecution on the basis of substantial assistance toward the prosecution of others. First-time, low-level, non-violent offenders may be able to avoid the mandatory minimums under the Controlled Substances Acts, if they are completely forthcoming. The most common imposed federal mandatory minimum sentences arise under the Controlled Substance and Controlled Substance Import and Export Acts, the provisions punishing the presence of a firearm in connection with a crime of violence or drug trafficking offense, the Armed Career Criminal Act, various sex crimes include child pornography, and aggravated identity theft. Critics argue that mandatory minimums undermine the rationale and operation of the federal sentencing guidelines which are designed to eliminate unwarranted sentencing disparity. Counter arguments suggest that the guidelines themselves operate to undermine individual sentencing discretion and that the ills attributed to other mandatory minimums are more appropriately assigned to prosecutorial discretion or other sources. State and federal mandatory minimums have come under constitutional attack on several grounds over the years, and have generally survived. -

Compounding Crimes: Time for Enforcement Merek Evan Lipson

Hastings Law Journal Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 5 1-1975 Compounding Crimes: Time for Enforcement Merek Evan Lipson Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Merek Evan Lipson, Compounding Crimes: Time for Enforcement, 27 Hastings L.J. 175 (1975). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol27/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPOUNDING CRIMES: TIME FOR ENFORCEMENT? Compounding is a largely obscure part of American criminal law, and compounding statutes have become dusty weapons in the prosecu- tor's arsenal. An examination of this crime reveals few recently re- ported cases. Its formative case law evolved primarily during the nine- teenth and early twentieth centuries. As a result, one might expect to find that few states still retain compounding provisions in their stat- ute books. The truth, however, is quite to the contrary: compounding laws can be found in forty-five states.1 This note will define the compounding of crimes, offer a brief re- view of its nature and development to provide perspective, and distin- guish it from related crimes. It will analyze current American com- pounding law, explore why enforcement of compounding laws is dis- favored, and suggest that more vigorous enforcement may be appropri- ate, especially as a weapon against white collar crime. -

Nebraska Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS)

Nebraska Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) Manual for Automated Agencies November, 2000 Nebraska Commission on Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice 301 Centennial Mall South, P.O. Box 94946 Lincoln, Nebraska 68509-4946 (402) 471-2194 TABLE OF CONTENTS NEBRASKA INCIDENT-BASED REPORTING SYSTEM (NIBRS) ........................ 1 Definition of "Incident” ...................................................... 4 DATA REQUIREMENTS .......................................................... 7 Requirements for each Group A Offense ......................................... 8 Requirements for Arrests for Group A and Group B Offenses ......................... 15 DEFINITIONS OF BASIC CORE, ADDITIONAL DATA ELEMENT AND ARRESTEE ELEMENTS Age .................................................................... 17 Aggravated Assault / Homicide Circumstances .................................... 17 Armed With . 18 Arrest Date . 19 Arrest (Transaction) Number ................................................. 19 Arrest Offense Code ........................................................ 19 Attempted / Completed ..................................................... 19 Criminal Activity Type ..................................................... 20 Date Recovered ........................................................... 20 Disposition of Arrestee Under Age 18 .......................................... 20 Drug Type / Type Criminal Activity (Arrestee) ................................... 21 Estimated Drug Quantity / Type Drug Measurement .............................. -

Misprison of Felony

South Carolina Law Review Volume 6 Issue 1 Article 8 Fall 9-1-1953 Misprison of Felony E. L. Morgan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation E. Lee Morgan, Misprison of Felony, 6 S.C.L.R. 87. (1953). This Note is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Morgan: Misprison of Felony MISPRISION OF FELONY Misprision1 of felony has been defined in various ways, but per- haps its best definition is as follows: "Misprision of felony at common law is a criminal neglect either to prevent a felony from being committed or to bring the offender to justice after its com- mission, but without such previous concert with or subsequent assis- tance of him as will make the concealer an accessory before or after 12 the fact." In the modern use of the term, misprision of felony has been said to be almost, if not identically, the same offense as that of an acces- sory after the fact.3 It has also been stated that misprision is nothing more than a word used to describe a misdemeanor which does not possess a specific name.4 It is that offense of concealing a felony committed by another, but without such previous concert with or subsequent assistance to the felon as would make the concealing party an accessory before or after the fact.5 Misprision is distinguished from compounding an offense on the basis of consideration or amends; misprision is a bare concealment of crime, while compounding is a concealment for a reward by one 6 directly injured by the crime. -

Why the Eighth Amendment Bans Charging Juveniles with Felony Murder

Boston College Law Review Volume 61 Issue 8 Article 6 11-24-2020 Cruel and Unusual: Why the Eighth Amendment Bans Charging Juveniles with Felony Murder Cameron Casey Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Juvenile Law Commons, and the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Recommended Citation Cameron Casey, Cruel and Unusual: Why the Eighth Amendment Bans Charging Juveniles with Felony Murder, 61 B.C. L. Rev. 2965 (2020), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol61/iss8/6 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRUEL AND UNUSUAL: WHY THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT BANS CHARGING JUVENILES WITH FELONY MURDER Abstract: The intersection of Supreme Court jurisprudence on the Eighth Amendment, felony murder, and juvenile justice supports the conclusion that it is unconstitutional to charge juveniles who did not kill, attempt to kill, or intend to kill with felony murder—a doctrine that allows individuals who unintentionally kill while committing a felony to be charged with murder. The Supreme Court has acknowledged that juveniles are different from adults because they lack ma- turity and the ability to understand the consequences of their actions. The felony murder doctrine hinges on a defendant’s anticipation of what might occur when carrying out a felony; thus, it cannot be applied to juveniles who did not kill, at- tempt to kill, or intend to kill because juveniles, unlike adults, lack the capacity to anticipate negative results from their actions. -

Supreme Court of the United States Petition for Writ of Certiorari

18--7897 TN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STAIET FILED ' LARAEL OWENS., Larael K Owens 07 MARIA ZUCKER, MICHEL P MCDANIEL, POLK COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE, MARK MCMANN, TAMESHA SADDLERS. RESPONDENT(S) Case No. 18-12480 Case No. 8:18-cv-00552-JSM-JSS THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI Larael K Owens 2 Summer lake way Savannah GA 31407 (229)854-4989 RECE11VED 2019 I OFFICE OF THE CLERK I FLSUPREME COURT, U.sJ Z-L QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1.Does a State Judges have authority to preside over a case when He/She has a conflicts of interest Does absolute immunity apply when ajudge has acted criminally under color of law and without jurisdiction, as well as actions taken in an administrative capacity to influence cases? 2.Does Eleventh Amendment immunity apply when officers of the court have violated 31 U.S. Code § 3729 and the state has refused to provide any type of declaratory relief? 3.Does Title IV-D, Section 458 of the Social Security Act violate the United States Constitution due to the incentives it creates for the court to willfully violate civil rights of parties in child custody and support cases? 4.Has the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit erred in basing its decision on the rulings of a Federal judge who has clearly and willfully violated 28 U.S. Code § 455. .Can a state force a bill of attainder on a natural person in force you into slavery 6.Can a judge have Immunity for their non judicial activities who knowingly violate civil rights 2. -

602KB***Composition – Legal and Theoretical Foundations

462 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (2015) 27 SAcLJ COMPOSITION Legal and Theoretical Foundations The composition of offences has been an integral part of the Singapore criminal justice system from its inception. This article sets out the legal and theoretical foundations for composition, as well as its historical genesis within our Criminal Procedure Code – from its roots in English law to its statutory entrenchment in India and the Straits Settlements. The recent amendments to the Criminal Procedure Code and its effect on composition in our penal system will also be examined. Ryan David LIM LLB (Hons) (Nott); Deputy Public Prosecutor, Attorney-General’s Chambers, Singapore. Selene YAP BA (Hons) (National University of Singapore), JD (Melb); Deputy Public Prosecutor, Attorney-General’s Chambers, Singapore. I. Historical genesis of composition A. English common law1 1 At first blush, composition appears to be an aberration in criminal law. As K S Rajah observes in his article “Composition and Due Process”:2 A crime is regarded as a wrong done to society. The offender and the victim are not normally allowed to come to an agreement to absolve the offender from criminal responsibility. 2 Indeed, the compounding of a felony – a prosecutor or a victim accepting consideration in return for not prosecuting a felony – was an offence under English common law.3 The compounding of theft 1 For a comprehensive history of the composition of offences in English law, see Percy Henry Winfield, The Present Law of Abuse of Legal Procedure (Cambridge University Press, 2013) at p 117. 2 K S Rajah, “Composition and Due Process” (2004) Law Gazette <http://www.lawgazette.com.sg/2004-1/Jan04-col.htm> (accessed 3 June 2014). -

1 PUBLIC JUSTICE OFFENCES Hindering Investigations

PUBLIC JUSTICE OFFENCES Hindering investigations; concealing offences and attempting to pervert the course of justice Reasonable Cause Criminal Law CLE Conference 28 March 2015 Part 7 of the Crimes Act 1900 was introduced as a package of Public Justice Offences inserted into the Crimes Act in 1990.1 The purpose of the package was to create a comprehensive statement of the law relating to public justice offences which, until the enactment of the amendments, was described by the then Attorney General Mr John Dowd as “fragmented and confusing, consisting of various common law and statutory provisions, with many gaps, anomalies and uncertainties”.2 Part 7 Division 2 deals broadly with offences concerning the interference in the administration of justice. This paper does not aim to cover every aspect of the package of public justice offences but focuses on the principal offences incorporated within Division 2, being Ss. 315, 316 and 319 offences, and their common law equivalents. Background Up until 25 November 1990, the various common law offences including misprision of felony, hindering an investigation, compounding a felony and perverting the course of justice, to name a few, operated, until abolished by the Crimes (Public Justice) Amendment Act 19903. From 25 November 1990, Part 7 of the Crimes Act 1900 provided for ‘public justice offences’ broadly described as offences targeting interference with the administration 1 Inserted by the Crimes (Public Justice) Amendment Act 1990 (NSW) s 3, Sch 1. 2 New South Wales, Parliamentary Debates (Hansard) Legislative Assembly, 17 May 1990, the Hon JRA Dowd, Attorney General, Second Reading Speech at 3692. -

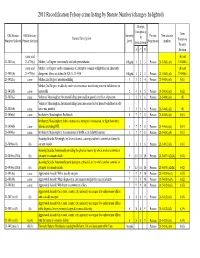

2011 Recodification Felony Crime Listing by Statute Number (Changes Hi-Lighted)

2011 Recodification Felony crime listing by Statute Number (changes hi-lighted) Attempt, Conspiracy, Old Statute Old Statutory Severity Person New statute New Statute Description & Number Violated Penalty Section Level Nonperson number Statutory Solicitation Penalty A C S Section same and (b) and 21-3401(a) 21-4706(c) Murder; 1st Degree; intentionally and with premeditation Off-grid 1 2 3 Person 21-5402(a)(1) 21-6806(c) same and Murder; 1st Degree; in the commission of, attempt to commit, or flight from an inherently (b) and 21-3401(b) 21-4706(c) dangerous felony as defined in K.S.A. 21-3436 Off-grid 1 2 3 Person 21-5402(a)(2) 21-6806(c) 21-3402(a) same Murder; 2nd Degree; intentional killing 1 3 3 4 Person 21-5403(a)(1) (b)(1) Murder; 2nd Degree; recklessly, under circumstances manifesting extreme indifference to 21-3402(b) same human life 2 4 4 5 Person 21-5403(a)(2) (b)(2) 21-3403(a) same Voluntary Manslaughter; Intentional killing upon sudden quarrel or in heat of passion 3 5 5 6 Person 21-5404(a)(1) (b) Voluntary Manslaughter; Intentional killing upon unreasonable but honest belief that deadly 21-3403(b) same force was justified 3 5 5 6 Person 21-5404(a)(2) (b) 21-3404(a) same Involuntary Manslaughter; Recklessly 5 7 7 8 Person 21-5405(a)(1) (b)(1) Involuntary Manslaughter; In the commission, attempted commission, or flight from other 21-3404(b) same felonies excluding DUI 5 7 7 8 Person 21-5405(a)(2) (b)(1) 21-3404(c) same Involuntary Manslaughter; In commission of lawful act in unlawful manner 5 7 7 8 Person 21-5405(a)(4) (b)(1)