Compoundability of Offences: Tracing the Shift in the Priorities of Criminal Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tainted by Torture Examining the Use of Torture Evidence a Report by Fair Trials and REDRESS May 2018

Tainted by Torture Examining the Use of Torture Evidence A report by Fair Trials and REDRESS May 2018 1 Fair Trials is a global criminal justice watchdog with offices in London, Brussels and Washington, D.C., focused on improving the right to a fair trial in accordance with international standards. Fair Trials’ work is premised on the belief that fair Its work combines: (a) helping suspects to trials are one of the cornerstones of a just society: understand and exercise their rights; (b) building an they prevent lives from being ruined by miscarriages engaged and informed network of fair trial defenders of justice, and make societies safer by contributing to (including NGOs, lawyers and academics); and (c) transparent and reliable justice systems that maintain fighting the underlying causes of unfair trials through public trust. Although universally recognised in research, litigation, political advocacy and campaigns. principle, in practice the basic human right to a fair trial is being routinely abused. Contacts: Jago Russell Roseanne Burke Chief Executive Legal and Communications Assistant [email protected] [email protected] For press queries, please contact: Alex Mik Campaigns and Communications Manager [email protected] +44 (0)207 822 2370 For more information about Fair Trials: Web: www.fairtrials.net Twitter: @fairtrials 2 Tainted by Torture: Examining the Use of Torture Evidence | 2018 REDRESS is an international human rights organisation that represents victims of torture and related international crimes to obtain justice and reparation. REDRESS brings legal cases on behalf of individual Its work includes research and advocacy to identify victims of torture, and advocates for better laws to the changes in law, policy and practice that are provide effective reparations. -

Incest Statutes

Statutory Compilation Regarding Incest Statutes March 2013 Scope This document is a comprehensive compilation of incest statutes from U.S. state, territorial, and the federal jurisdictions. It is up-to-date as of March 2013. For further assistance, consult the National District Attorneys Association’s National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse at 703.549.9222, or via the free online prosecution assistance service http://www.ndaa.org/ta_form.php. *The statutes in this compilation are current as of March 2013. Please be advised that these statutes are subject to change in forthcoming legislation and Shepardizing is recommended. 1 National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse National District Attorneys Association Table of Contents ALABAMA .................................................................................................................................................................. 8 ALA. CODE § 13A-13-3 (2013). INCEST .................................................................................................................... 8 ALA. CODE § 30-1-3 (2013). LEGITIMACY OF ISSUE OF INCESTUOUS MARRIAGES ...................................................... 8 ALASKA ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 ALASKA STAT. § 11.41.450 (2013). INCEST .............................................................................................................. 8 ALASKA R. EVID. RULE 505 (2013) -

Criminal Law and Litigation CPD Update

prepared for Criminal Law and Litigation CPD Update Andrew Clemes CPD Training 2008 edition in Law ILEX CPD reference code: L22/P22 CPD © 2008 Copyright ILEX Tutorial College Limited All materials included in this ITC publication are copyright protected. All rights reserved. Any unauthorised reproduction or transmission of any part of this publication, whether electronically or otherwise, will constitute an infringement of copyright. No part of this publication may be lent, resold or hired out for any purpose without the prior written permission of ILEX Tutorial College Ltd. WARNING: Any person carrying out an unauthorised act in relation to this copyright work may be liable to both criminal prosecution and a civil claim for damages. This publication is intended only for the purpose of private study. Its contents were believed to be correct at the time of publication or any date stated in any preface, whichever is the earlier. This publication does not constitute any form of legal advice to any person or organisation. ILEX Tutorial College Ltd will not be liable for any loss or damage of any description caused by the reliance of any person on any part of the contents of this publication. Published in 2008 by: ILEX Tutorial College Ltd College House Manor Drive Kempston Bedford United Kingdom MK42 7AB Preface This update has been prepared by ILEX Tutorial College (ITC) to assist Fellows and Members of the Institute of Legal Executives (ILEX) in meeting their continuing professional development (CPD) or lifelong learning requirements for 2008. Fellows are required to complete 16 hours of CPD in 2008 and Members eight hours of CPD. -

A Comparison of R. V. Stone with R. V. Parks: Two Cases of Automatism

ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY A Comparison of R. v. Stone with R. v. Parks: Two Cases of Automatism Graham D. Glancy, MB, ChB, John M. Bradford, MB, ChB, and Larissa Fedak, BPE, MSc, LLB J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 30:541–7, 2002 Both the medical and legal professions recognize that The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Dis- some criminal actions take place in the absence of orders, fourth edition (DMS-IV),3 does not define consciousness and intent, thereby inferring that these automatism, although it does include several diag- actions are less culpable. However, experts enter a noses, such as delirium or parasomnias, that could be legal quagmire when medical expert evidence at- the basis for automatism. tempts to find some common meaning for the terms The seminal legal definition is that of Lord Den- “automatism” and “unconsciousness.” ning in Bratty v. A-G for Northern Ireland: 1 The Concise Oxford Dictionary defines autom- . .an act which is done by the muscles without any control by atism as “Involuntary action. (Psych) action per- the mind, such as a spasm, a reflex action, or a convulsion; or an formed unconsciously or subconsciously.” This act done by a person who is not conscious of what he is doing, seems precise and simple until we attempt to de- such as an act done while suffering from concussion or while 4 fine unconscious or subconscious. Fenwick2 notes sleepwalking. that consciousness is layered and that these layers This was developed by Canadian courts in R. v. Ra- largely depend on subjective behavior that is ill de- bey: fined. -

Nebraska Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS)

Nebraska Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) Manual for Automated Agencies November, 2000 Nebraska Commission on Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice 301 Centennial Mall South, P.O. Box 94946 Lincoln, Nebraska 68509-4946 (402) 471-2194 TABLE OF CONTENTS NEBRASKA INCIDENT-BASED REPORTING SYSTEM (NIBRS) ........................ 1 Definition of "Incident” ...................................................... 4 DATA REQUIREMENTS .......................................................... 7 Requirements for each Group A Offense ......................................... 8 Requirements for Arrests for Group A and Group B Offenses ......................... 15 DEFINITIONS OF BASIC CORE, ADDITIONAL DATA ELEMENT AND ARRESTEE ELEMENTS Age .................................................................... 17 Aggravated Assault / Homicide Circumstances .................................... 17 Armed With . 18 Arrest Date . 19 Arrest (Transaction) Number ................................................. 19 Arrest Offense Code ........................................................ 19 Attempted / Completed ..................................................... 19 Criminal Activity Type ..................................................... 20 Date Recovered ........................................................... 20 Disposition of Arrestee Under Age 18 .......................................... 20 Drug Type / Type Criminal Activity (Arrestee) ................................... 21 Estimated Drug Quantity / Type Drug Measurement .............................. -

Download Profile

Maryam Mir Call: 2011 Email: [email protected] Profile Maryam is a popular choice amongst lay and professional clients for her detailed preparation, fearless advocacy in court and personable nature. She is a compassionate listener who fights for her clients with determination and gets great results. Maryam has experience in a wide range of criminal offences. As a led junior, Maryam is instructed in cases involving homicide, firearms, terrorism and large scale fraud. As leading counsel, she has defended in cases of serious violence, conspiracy to supply firearms, politically motivated offending from terrorism to protest, financial crime, fraud and regulatory matters, sexual offences, drugs supply conspiracies and kidnapping. She worked on several high-profile terrorism cases during her secondment with Reprieve, representing leaders of political parties sanctioned as terrorists by the UN, US and UK. She was part of a team that brought the first due process challenge in the US against the inclusion of a US citizen on a “Kill List”, whilst reporting on the conflict in Syria. She has experience in cases involving legal challenges to the use of state extra-judicial killing by drones and/or mercenaries. She assists individuals challenging their listing by the UN Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee. Maryam is experienced in advising on appeals against conviction and sentence before the Criminal Division of the Court of Appeal. Maryam is determined to encourage other ethnic minority women to enter and stay in the profession. She -

Misprison of Felony

South Carolina Law Review Volume 6 Issue 1 Article 8 Fall 9-1-1953 Misprison of Felony E. L. Morgan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation E. Lee Morgan, Misprison of Felony, 6 S.C.L.R. 87. (1953). This Note is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Morgan: Misprison of Felony MISPRISION OF FELONY Misprision1 of felony has been defined in various ways, but per- haps its best definition is as follows: "Misprision of felony at common law is a criminal neglect either to prevent a felony from being committed or to bring the offender to justice after its com- mission, but without such previous concert with or subsequent assis- tance of him as will make the concealer an accessory before or after 12 the fact." In the modern use of the term, misprision of felony has been said to be almost, if not identically, the same offense as that of an acces- sory after the fact.3 It has also been stated that misprision is nothing more than a word used to describe a misdemeanor which does not possess a specific name.4 It is that offense of concealing a felony committed by another, but without such previous concert with or subsequent assistance to the felon as would make the concealing party an accessory before or after the fact.5 Misprision is distinguished from compounding an offense on the basis of consideration or amends; misprision is a bare concealment of crime, while compounding is a concealment for a reward by one 6 directly injured by the crime. -

INSANITY PLEA: a RETROSPECTIVE EXAMINATION of the VERDICT of "NOT GUILTY on the GROUND of INSANITY" Abstract

Document hosted at http://www.jdsupra.com/post/documentViewer.aspx?fid=34dc6c62-a9eb-49cf-b24a-f906ee2528c5 INSANITY PLEA: A RETROSPECTIVE EXAMINATION OF THE VERDICT OF "NOT GUILTY ON THE GROUND OF INSANITY" by Sally Ramage Abstract This paper argues that insanity should be eliminated as a separate defence, but that the effects of mental disorder should still carry signifcant moral weight in that mental illness should be relevant in assessing culpability only as warranted by general criminal law doctrines concerning mens rea, self-defence and duress. This study was triggered by the case R v Central Criminal Court, ex parte Peter William Young1 . Peter Young had been charged with dishonestly concealing material facts contrary to s47 (1) Financial services Act 1986. The case considered Peter Young's intentions, not in relation to dishonesty, and not in relation to the purpose of the making of the representations, but as to the state of the defendant's intention in relation to the facts. Leave to Appeal to the House of Lords was refused. Literature Review on English `insanity' caselaw No analysis of a legal issue is complete without a literature review of the subject. Stephen Gilchrist wrote a short article in 19992 in which he discussed the Court of Appeal decision in R v Antoine3 in which the defence of diminished responsibility under s.2 Homicide Act 1957 applied. In the year 2000, Sean Enright4 wrote a one- page review on the power to commit defendants acquitted on the grounds of insanity to a mental institution for an unlimited period. He reviewed two cases R v Maidstone Crown Court, ex parte Harrow London Borough Council [2001 and R v Crown Court at Snaresbrook, exparte Director of the Serious Fraud Ofce [19971. -

602KB***Composition – Legal and Theoretical Foundations

462 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (2015) 27 SAcLJ COMPOSITION Legal and Theoretical Foundations The composition of offences has been an integral part of the Singapore criminal justice system from its inception. This article sets out the legal and theoretical foundations for composition, as well as its historical genesis within our Criminal Procedure Code – from its roots in English law to its statutory entrenchment in India and the Straits Settlements. The recent amendments to the Criminal Procedure Code and its effect on composition in our penal system will also be examined. Ryan David LIM LLB (Hons) (Nott); Deputy Public Prosecutor, Attorney-General’s Chambers, Singapore. Selene YAP BA (Hons) (National University of Singapore), JD (Melb); Deputy Public Prosecutor, Attorney-General’s Chambers, Singapore. I. Historical genesis of composition A. English common law1 1 At first blush, composition appears to be an aberration in criminal law. As K S Rajah observes in his article “Composition and Due Process”:2 A crime is regarded as a wrong done to society. The offender and the victim are not normally allowed to come to an agreement to absolve the offender from criminal responsibility. 2 Indeed, the compounding of a felony – a prosecutor or a victim accepting consideration in return for not prosecuting a felony – was an offence under English common law.3 The compounding of theft 1 For a comprehensive history of the composition of offences in English law, see Percy Henry Winfield, The Present Law of Abuse of Legal Procedure (Cambridge University Press, 2013) at p 117. 2 K S Rajah, “Composition and Due Process” (2004) Law Gazette <http://www.lawgazette.com.sg/2004-1/Jan04-col.htm> (accessed 3 June 2014). -

1 PUBLIC JUSTICE OFFENCES Hindering Investigations

PUBLIC JUSTICE OFFENCES Hindering investigations; concealing offences and attempting to pervert the course of justice Reasonable Cause Criminal Law CLE Conference 28 March 2015 Part 7 of the Crimes Act 1900 was introduced as a package of Public Justice Offences inserted into the Crimes Act in 1990.1 The purpose of the package was to create a comprehensive statement of the law relating to public justice offences which, until the enactment of the amendments, was described by the then Attorney General Mr John Dowd as “fragmented and confusing, consisting of various common law and statutory provisions, with many gaps, anomalies and uncertainties”.2 Part 7 Division 2 deals broadly with offences concerning the interference in the administration of justice. This paper does not aim to cover every aspect of the package of public justice offences but focuses on the principal offences incorporated within Division 2, being Ss. 315, 316 and 319 offences, and their common law equivalents. Background Up until 25 November 1990, the various common law offences including misprision of felony, hindering an investigation, compounding a felony and perverting the course of justice, to name a few, operated, until abolished by the Crimes (Public Justice) Amendment Act 19903. From 25 November 1990, Part 7 of the Crimes Act 1900 provided for ‘public justice offences’ broadly described as offences targeting interference with the administration 1 Inserted by the Crimes (Public Justice) Amendment Act 1990 (NSW) s 3, Sch 1. 2 New South Wales, Parliamentary Debates (Hansard) Legislative Assembly, 17 May 1990, the Hon JRA Dowd, Attorney General, Second Reading Speech at 3692. -

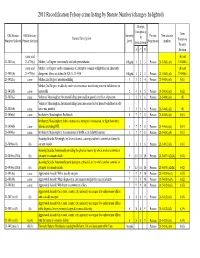

2011 Recodification Felony Crime Listing by Statute Number (Changes Hi-Lighted)

2011 Recodification Felony crime listing by Statute Number (changes hi-lighted) Attempt, Conspiracy, Old Statute Old Statutory Severity Person New statute New Statute Description & Number Violated Penalty Section Level Nonperson number Statutory Solicitation Penalty A C S Section same and (b) and 21-3401(a) 21-4706(c) Murder; 1st Degree; intentionally and with premeditation Off-grid 1 2 3 Person 21-5402(a)(1) 21-6806(c) same and Murder; 1st Degree; in the commission of, attempt to commit, or flight from an inherently (b) and 21-3401(b) 21-4706(c) dangerous felony as defined in K.S.A. 21-3436 Off-grid 1 2 3 Person 21-5402(a)(2) 21-6806(c) 21-3402(a) same Murder; 2nd Degree; intentional killing 1 3 3 4 Person 21-5403(a)(1) (b)(1) Murder; 2nd Degree; recklessly, under circumstances manifesting extreme indifference to 21-3402(b) same human life 2 4 4 5 Person 21-5403(a)(2) (b)(2) 21-3403(a) same Voluntary Manslaughter; Intentional killing upon sudden quarrel or in heat of passion 3 5 5 6 Person 21-5404(a)(1) (b) Voluntary Manslaughter; Intentional killing upon unreasonable but honest belief that deadly 21-3403(b) same force was justified 3 5 5 6 Person 21-5404(a)(2) (b) 21-3404(a) same Involuntary Manslaughter; Recklessly 5 7 7 8 Person 21-5405(a)(1) (b)(1) Involuntary Manslaughter; In the commission, attempted commission, or flight from other 21-3404(b) same felonies excluding DUI 5 7 7 8 Person 21-5405(a)(2) (b)(1) 21-3404(c) same Involuntary Manslaughter; In commission of lawful act in unlawful manner 5 7 7 8 Person 21-5405(a)(4) (b)(1) -

National Incident-Based Reporting System Volume 1: Data Collection Guidelines

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Criminal Justice Information Services Division Uniform Crime Reporting National Incident-Based Reporting System Volume 1: Data Collection Guidelines August 2000 NATIONAL INCIDENT-BASED REPORTING SYSTEM VOLUME 1: DATA COLLECTION GUIDELINES Prepared by U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Criminal Justice Information Services Division Uniform Crime Reporting Program August 2000 FOREWORD Information about the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) is contained in the four documents described below: Volume 1: Data Collection Guidelines This document is for the use of local, state, and federal Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program personnel (i.e., administrators, training instructors, report analysts, coders, data entry clerks, etc.) who are responsible for collecting and recording NIBRS crime data for submission to the FBI. It contains a system overview and descriptions of the offenses, offense codes, reports, data elements, and data values used in the system. Volume 2: Data Submission Specifications This document is for the use of local, state, and federal systems personnel (i.e., computer programmers, analysts, etc.) who are responsible for preparing magnetic media for submission to the FBI. It contains the data submission instructions for magnetic media, record layouts, and error-handling procedures that must be followed in submitting magnetic media to the FBI for NIBRS reporting purposes. Volume 3: Approaches to Implementing an Incident-Based Reporting (IBR) System This document is for the use of local, state, and federal systems personnel (i.e., computer programmers, analysts, etc.) who are responsible for developing an IBR system that will meet NIBRS’s reporting requirements.