Musical and Dramatic Structure in the Opera Buffa Finale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antonio Salieri's Revenge

Antonio Salieri’s Revenge newyorker.com/magazine/2019/06/03/antonio-salieris-revenge By Alex Ross 1/13 Many composers are megalomaniacs or misanthropes. Salieri was neither. Illustration by Agostino Iacurci On a chilly, wet day in late November, I visited the Central Cemetery, in Vienna, where 2/13 several of the most familiar figures in musical history lie buried. In a musicians’ grove at the heart of the complex, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms rest in close proximity, with a monument to Mozart standing nearby. According to statistics compiled by the Web site Bachtrack, works by those four gentlemen appear in roughly a third of concerts presented around the world in a typical year. Beethoven, whose two-hundred-and-fiftieth birthday arrives next year, will supply a fifth of Carnegie Hall’s 2019-20 season. When I entered the cemetery, I turned left, disregarding Beethoven and company. Along the perimeter wall, I passed an array of lesser-known but not uninteresting figures: Simon Sechter, who gave a counterpoint lesson to Schubert; Theodor Puschmann, an alienist best remembered for having accused Wagner of being an erotomaniac; Carl Czerny, the composer of piano exercises that have tortured generations of students; and Eusebius Mandyczewski, a magnificently named colleague of Brahms. Amid these miscellaneous worthies, resting beneath a noble but unpretentious obelisk, is the composer Antonio Salieri, Kapellmeister to the emperor of Austria. I had brought a rose, thinking that the grave might be a neglected and cheerless place. Salieri is one of history’s all-time losers—a bystander run over by a Mack truck of malicious gossip. -

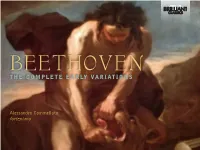

The Complete Early Variations

BEETHOVEN THE COMPLETE EARLY VARIATIONS Alessandro Commellato fortepiano Ludwig van Beethoven 1770-1827 1. 32 Variations in C minor 8. 10 Variation in B flat WoO73 14. 8 Variations in C WoO67 WoO80 on an original theme 11’43 on Salieri’s air ‘La stessa on a theme by Count Waldstein 2. 5 Variations in D WoO79 la stessissima’ 12’28 for piano four hands 8’58 on ‘Rule Britannia’ 5’36 9. 8 Variations in C WoO72 on 15. 13 Variations in A WoO66 3. 7 Variations in D WoO78 Grétry’s air ‘Un fievre brûlante’ 7’12 on Dittersdorf’s air ‘Es war on ‘God save the King’ 8’43 10. 12 Variations in A WoO71 on a einmal ein alter Mann’ 14’55 4. 6 Easy Variations in G WoO77 Russian Dance from Wranitsky’s 16. 24 Variations in D WoO65 on an original theme 7’27 ballet ‘Das Waldmädchen’ 12’20 on Righini’s air ‘Venni amore’ 23’29 5. 8 Variations in F WoO76 11. 6 Variations in G WoO70 17. 6 Easy Variations in F WoO64 from Süssmayr’s theme on Paisiello's air on a Swiss air 2’57 ‘Tändeln und Scherzen’ 9’21 ‘Nel cor più non mi sento’ 5’45 18. 9 Variations in C minor WoO63 6. 7 Variations in F WoO75 12. 9 Variations in A WoO69 on on a march by Dressler 12’41 from Winter’s opera ‘Das Paisiello’s air ‘Quant’è più bello’ 6’07 unterbrochene Opferfest’ 11’54 13. 12 Variations in C WoO68 Alessandro Commellato fortepiano 7. -

MUI Demands Restoration of RTÉ NSO Posts

Volume 10 No. 4 | Winter 2012 Sound Post | Winter 2012 INTERVAL QUIZ FIM Pursuing 1. Where are the Irish composers, Michael Balfe and William Wallace, buried? Musicians’ Grievance 2. At which venue did the Beatles appear in Dublin in the early with Airlines 1960s? 3. Which former Irish Government minister wrote a biography Despite the fact that the petition launched this summer by the entitled, The Great Melody? International Federation of Musicians (FIM) has already collected more than 40,000 signatures, EU Commissioner for Transport, 4. Who composed the well-known Siim Kallas, is still refusing to include specific provisions which waltz, Waves of the Danube? take account of problems encountered by musicians travelling by 5. With which instrument was NEWSLETTER • OF • THE • MUI: MUSICIANS’ UNION OF IRELAND plane with their instrument into the revised 261/2004 regulation George Formby associated? on passenger rights. IN THIS ISSUE: 6. Which musical instrument is MUI demands restoration of full In a letter dated 24th July, 2012, mobility is restricted and their mentioned in the title of the 2001 strength NSO he nevertheless indicates that he activity consequently curtailed. film starring Nicholas Cage and understands these problems and Pénelope Cruz? FIM is continuing in its efforts, in MUI Demands Peter Healy, former MUI RTÉ CO recognises that, on account of Officer, retires unforeseeable situations with which liaison with others, including Euro- 7. What is the stage name of the pean MP, Georges Bach, to deter- American singer and songwriter, musicians are faced during check- MUI RTÉ freelance orchestral mine the most suitable means for Stefani Joanne Angelina German- in or boarding, their professional otta? Restoration of rates making headway on this issue. -

Anathema of Venice: Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart's

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 33, Number 46, November 17, 2006 EIRFeature ANATHEMA OF VENICE Lorenzo Da Ponte: Mozart’s ‘American’ Librettist by Susan W. Bowen and made a revolution in opera, who was kicked out of Venice by the Inquisition because of his ideas, who, emigrating to The Librettist of Venice; The Remarkable America where he introduced the works of Dante Alighieri Life of Lorenzo Da Ponte; Mozart’s Poet, and Italian opera, and found himself among the circles of the Casanova’s Friend, and Italian Opera’s American System thinkers in Philadelphia and New York, Impresario in America was “not political”? It became obvious that the glaring omis- by Rodney Bolt Edinburgh, U.K.: Bloomsbury, 2006 sion in Rodney Bolt’s book is the “American hypothesis.” 428 pages, hardbound, $29.95 Any truly authentic biography of this Classi- cal scholar, arch-enemy of sophistry, and inde- As the 250th anniversary of the birth of Wolfgang Amadeus fatigable promoter of Mozart approached, I was happy to see the appearance of this creativity in science and new biography of Lorenzo Da Ponte, librettist for Mozart’s art, must needs bring to three famous operas against the European oligarchy, Mar- light that truth which riage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Cosi fan tutte. The story Venice, even today, of the life of Lorenzo Da Ponte has been entertaining students would wish to suppress: of Italian for two centuries, from his humble roots in the that Lorenzo Da Ponte, Jewish ghetto, beginning in 1749, through his days as a semi- (1749-1838), like Mo- nary student and vice rector and priest, Venetian lover and zart, (1756-91), was a gambler, poet at the Vienna Court of Emperor Joseph II, product of, and also a through his crowning achievement as Mozart’s collaborator champion of the Ameri- in revolutionizing opera; to bookseller, printer, merchant, de- can Revolution and the voted husband, and librettist in London in the 1790s, with Renaissance idea of man stops along the way in Padua, Trieste, Brussels, Holland, Flor- that it represented. -

3 – 2018 «Cave Tropone» A. Salieri to a Libretto by G. Casti

№ 3 – 2018 «Cave Tropone» A. Salieri to a libretto by G. Casti: about reason and feeling in the educational era ……………………………………………............ 56 Olga S. Poroshenkova (Moscow) — Post-graduate Student of the State Institute for Art Studies, Editor of the Literary Part of the Moscow Theater «New Opera». E-mail: [email protected] La Grotta di Trofonio on Giovanni Battista Casti’s libretto is one of the composer’s most popular operas. The librettist and the composer next to him neglect some of the opera buffa plot features and touch some important problems of XVIII century. What is stronger — human’s will or their destiny? What side of human personality is more important — urge to happiness or to wisdom? Do the feelings or the sense win? This article reviews the libretto plot characteristics and their musical embodiment. Keywords: Salieri, Casti, opera buffa, the Enlightenment, will, destiny. ЛИТЕРАТУРА 1. Горохова Р.М. Касти, Джамбаттиста // Электронные публикации Института русской литературы (Пушкинского дома) РАН. URL: http://lib.pushkinskijdom.ru/Default.aspx?tabid=313 (дата обращения: 01.07.2017). 2. Дидро Д. Систематическое опровержение книги Гельвеция «Человек» / Д. Дидро // Собр. соч. М.-Л., 1935. Т. 2. 584 с. 3. Кириллина Л.В. Галантность и чувствительность в музыке XVIII века. // Гетевские чтения. М.: Наука, 2003. URL: http://21israel-music.net/Galante.htm (дата обращения: 08.12.2017). 4. Кириллина Л.В. Пасынок истории // Музыкальная академия. 2000. № 3. С. 53–73. 5. Луканина О.Н. Проблема «женского» в философии эпохи Просвещения // Вестник Московского государственного университета культуры и искусств. М., 2010. № 2. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/v/problema-zhenskogo-v-filosofii-epohi-prosvescheniya (дата обращения: 09.08.2018). -

Les Talens Lyriques the Ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, Which Takes Its

Les Talens Lyriques The ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, which takes its name from the subtitle of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Les Fêtes d’Hébé (1739), was formed in 1991 by the harpsichordist and conductor Christophe Rousset. Championing a broad vocal and instrumental repertoire, ranging from early Baroque to the beginnings of Romanticism, the musicians of Les Talens Lyriques aim to throw light on the great masterpieces of musical history, while providing perspective by presenting rarer or little known works that are important as missing links in the European musical heritage. This musicological and editorial work, which contributes to its renown, is a priority for the ensemble. Les Talens Lyriques perform to date works by Monteverdi (L'Incoronazione di Poppea, Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, L’Orfeo), Cavalli (La Didone, La Calisto), Landi (La Morte d'Orfeo), Handel (Scipione, Riccardo Primo, Rinaldo, Admeto, Giulio Cesare, Serse, Arianna in Creta, Tamerlano, Ariodante, Semele, Alcina), Lully (Persée, Roland, Bellérophon, Phaéton, Amadis, Armide, Alceste), Desmarest (Vénus et Adonis), Mondonville (Les Fêtes de Paphos), Cimarosa (Il Mercato di Malmantile, Il Matrimonio segreto), Traetta (Antigona, Ippolito ed Aricia), Jommelli (Armida abbandonata), Martin y Soler (La Capricciosa corretta, Il Tutore burlato), Mozart (Mitridate, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Così fan tutte, Die Zauberflöte), Salieri (La Grotta di Trofonio, Les Danaïdes, Les Horaces, Tarare), Rameau (Zoroastre, Castor et Pollux, Les Indes galantes, Platée, Pygmalion), Gluck -

BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA 2018 – 25Th ANNIVERSARY SEASON NICOLÒ ISOUARD’S CINDERELLA (CENDRILLON)

BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA 2018 – 25th ANNIVERSARY SEASON NICOLÒ ISOUARD’s CINDERELLA (CENDRILLON) Performances: The Deanery Garden, Bampton, Oxfordshire: Friday, Saturday 20, 21 July The Orangery Theatre, Westonbirt School, Gloucestershire: Monday 27 August St John’s Smith Square, London: Tuesday 18 September Libretto: Charles Guillaume Etienne after the fairy-tale by Charles Perrault Sung in a new English translation by Gilly French, dialogues by Jeremy Gray Director: Jeremy Gray Conductor: Harry Sever Orchestra of Bampton Classical Opera (Bampton, Westonbirt) CHROMA (St John’s Smith Square) Bampton Classical Opera celebrates its 25th anniversary with the UK modern-times première of Nicolò Isouard’s Cinderella (1810), a charming and lyrical telling of Perrault’s much-loved fairy-tale, continuing the Company’s remarkable exploration of rarities from the classical period. The Bampton production will be sung in a new English translation by Gilly French with dialogues by Jeremy Gray. This new production also marks the bicentenary of the composer’s death in Paris in 1818. Cinderella (Cendrillon) is designated as an Opéra Féerie, and is in three acts, to a libretto by Charles Guillaume Etienne. Cinderella and her Prince share music of folktune-like simplicity, contrasting with the vain step-sisters, who battle it out with torrents of spectacular coloratura. With his gifts for unaffected melody, several appealing ensembles and always beguiling orchestration, Isouard’s Cinderella is ripe for rediscovery. Performances will be conducted by Harry Sever and directed by Jeremy Gray. Born in Malta in 1775, Isouard was renowned across Europe, composing 41 operas, many of which were published and widely performed. -

Songs of the Classical Age

Cedille Records CDR 90000 049 SONGS OF THE CLASSICAL AGE Patrice Michaels Bedi soprano David Schrader fortepiano 2 DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 049 S ONGS OF THE C LASSICAL A GE FRANZ JOSEF HAYDN MARIA THERESIA VON PARADIES 1 She Never Told Her Love.................. (3:10) br Morgenlied eines armen Mannes...........(2:47) 2 Fidelity.................................................... (4:04) WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART 3 Pleasing Pain......................................... (2:18) bs Cantata, K. 619 4 Piercing Eyes......................................... (1:44) “Die ihr des unermesslichen Weltalls”....... (7:32) 5 Sailor’s Song.......................................... (2:25) LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN VINCENZO RIGHINI bt Wonne der Wehmut, Op. 83, No. 1...... (2:11) 6 Placido zeffiretto.................................. (2:26) 7 SOPHIE WESTENHOLZ T’intendo, si, mio cor......................... (1:59) ck Morgenlied............................................. (3:24) 8 Mi lagnerò tacendo..............................(1:37) 9 Or che il cielo a me ti rende............... (3:07) FRANZ SCHUBERT bk Vorrei di te fidarmi.............................. (1:27) cl Frülingssehnsucht from Schwanengesang, D. 957..................... (4:06) CHEVALIER DE SAINT-GEORGES bl L’autre jour à l’ombrage..................... (2:46) PAULINE DUCHAMBGE cm La jalouse................................................ (2:22) NICOLA DALAYRAC FELICE BLANGINI bm Quand le bien-aimé reviendra............ (2:50) cn Il est parti!.............................................. (2:57) -

Larry Weng Piano

BEETHOVEN Larry Weng Piano Variations on themes by Grétry • Paisiello • Righini •Winter Sonata in C, WoO 51 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) relations with the changing governments of the period, as The opera Richard Coeur-de-lion (‘Richard the Lionheart’) Piano Variations on themes by Grétry, Paisiello, Righini and Winter Bourbons replaced Bonapartists and vice versa. Paisiello by André Grétry (1741–1813) was first performed at Piano Sonata in C major, WoO 51 • Waltzes, WoO 84 and 85 served at the court of Catherine II in Russia for eight years, Fontainebleau in 1785. The plot centres on the imprisonment and spent time in Vienna and Paris. His opera La molinara of Richard, taken captive as he returns from the Third Born in Bonn in 1770, Ludwig van Beethoven was the eldest 1827, his death the occasion of public mourning in Vienna. (‘The Mill Girl’), otherwise known as L’amor contrastato Crusade, and sought by his faithful minstrel, Blondel. Une son of a singer in the musical establishment of the The art of variation lies at the heart of a great deal of (‘Love Contrasted’), was originally written for carnival in fièvre brûlante (‘A Burning Fever’) has an important part to Archbishop-Elector of Cologne, and grandson of the music. Extended works may include movements consisting Naples in 1789. It was given several performances in Vienna play, heard by Richard, who joins in his favourite song, Archbishop’s former Kapellmeister, whose name he took. of variations, whether so titled or not. In improvisation in 1794, when Beethoven is said to have heard it, and he hearing Blondel sing from outside the castle where he is The household was not a happy one. -

Don Giovanni Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards

Opera Box 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards. See the Unit Overview for a detailed explanation. Before returning the box, please fill out the Evaluation Form at the end of the Teacher’s Guide. As this project is new, your feedback is imperative. Comments and ideas from you – the educators who actually use it – will help shape the content for future boxes. In addition, you are encouraged to include any original lesson plans. The Teacher’s Guide is intended to be a living reference book that will provide inspiration for other teachers. If you feel comfortable, include a name and number for future contact from teachers who might have questions regarding your lessons and to give credit for your original ideas. You may leave lesson plans in the Opera Box or mail them in separately. Before returning, please double check that everything has been assembled. The deposit money will be held until I personally check that everything has been returned (i.e. CDs having been put back in the cases). -

Scientific Comparison of Mozart and Salieri

Scientific comparison of Mozart and Salieri Mikhail Simkin "Do you feel quite sure of that, Dorian?" Our respondents failed the test. But could this be because they are a bunch of vulgar in taste "Quite sure." philistines? Fortunately, the quizzing software [2] records IP address, from which one can infer the "Ah! then it must be an illusion. The things one feels location of taker’s computer. Thus, I was able to absolutely certain about are never true. That is the fatality of faith, and the lesson of romance. How grave select the test scores received by people who you are! Don't be so serious. What have you or I to do downloaded the quiz from elite locations. For the with the superstitions of our age? … Play me something. analysis I chose Ivy League schools and Oxbridge Play me a nocturne, Dorian ..." (if not for any other reason, than because I did time in those places). The average elite score is 6.25 out -- Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray of 10 or 62.5% correct. Do you feel quite sure that Mozart was a genius and Salieri an envious mediocrity, and that their music 3000 cannot be even compared? To check whether this is an illusion I wrote the 2500 "Mozart or Salieri?" quiz [1]. It consists of ten one-minute audio clips. Some of them are from Mozart, other – from Salieri. The takers are to 2000 determine the composer. Though I selected some of the most acclaimed Mozart’s music for the quiz, people had great difficulties doing it. -

COJ Article Clean Draft 1

[THIS IS AN EARLY DRAFT (APOLOGIES!): PLEASE DO NOT CIRCULATE] ‘Sounds that float over us from the days of our ancestors’: Italian Opera and Nostalgia in Berlin, 1800-1815 Katherine Hambridge To talk of an identity crisis in Berlin at the end of the eighteenth century might sound curiously anachronistic, if not a little crass – but one writer in 1799 expressed the situation in exactly these terms, and at the level of the entire state: All parties agree that we are living in a moment when one of the greatest epochs in the revolution of humanity begins, and which, more than all previous momentous events, will be important for the spirit of the state. At such a convulsion the character of the latter emerges more than ever, [and] the truth becomes more apparent than ever, that lack of character for a state would be yet as dangerous an affliction, as it would for individual humans.1 The anxiety underlying this writer’s carefully hypothetical introduction – which resonates in several other articles in the four-year run of the Berlin publication, the Jahrbücher der preußichen Monarchie – is palpable. Not only were Prussia’s values and organising principles called into question by the convulsion referred to here – the French revolution – and its rhetoric of liberté, égalité, fraternité (not to mention the beheading of the royal family); so too was the state’s capacity to defend them. Forced to settle with France at the 1795 Peace of Basel, Prussia witnessed from the sidelines of official neutrality Napoleon’s manoeuvres around Europe over the next ten years, each victory a threat to this ‘peace’.