COJ Article Clean Draft 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

103 the Music Library of the Warsaw Theatre in The

A. ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA, MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW..., ARMUD6 47/1-2 (2016) 103-116 103 THE MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW THEATRE IN THE YEARS 1788 AND 1797: AN EXPRESSION OF THE MIGRATION OF EUROPEAN REPERTOIRE ALINA ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA UDK / UDC: 78.089.62”17”WARSAW University of Warsaw, Institute of Musicology, Izvorni znanstveni rad / Research Paper ul. Krakowskie Przedmieście 32, Primljeno / Received: 31. 8. 2016. 00-325 WARSAW, Poland Prihvaćeno / Accepted: 29. 9. 2016. Abstract In the Polish–Lithuanian Common- number of works is impressive: it included 245 wealth’s fi rst public theatre, operating in War- staged Italian, French, German, and Polish saw during the reign of Stanislaus Augustus operas and a further 61 operas listed in the cata- Poniatowski, numerous stage works were logues, as well as 106 documented ballets and perform ed in the years 1765-1767 and 1774-1794: another 47 catalogued ones. Amongst operas, Italian, French, German, and Polish operas as Italian ones were most popular with 102 docu- well ballets, while public concerts, organised at mented and 20 archived titles (totalling 122 the Warsaw theatre from the mid-1770s, featured works), followed by Polish (including transla- dozens of instrumental works including sym- tions of foreign works) with 58 and 1 titles phonies, overtures, concertos, variations as well respectively; French with 44 and 34 (totalling 78 as vocal-instrumental works - oratorios, opera compositions), and German operas with 41 and arias and ensembles, cantatas, and so forth. The 6 works, respectively. author analyses the manuscript catalogues of those scores (sheet music did not survive) held Keywords: music library, Warsaw, 18th at the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych in War- century, Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, saw (Pl-Wagad), in the Archive of Prince Joseph musical repertoire, musical theatre, music mi- Poniatowski and Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz- gration Poniatowska. -

Discovery Marche.Pdf

the MARCHE region Discovering VADEMECUM FOR THE TOURIST OF THE THIRD MILLENNIUM Discovering THE MARCHE REGION MARCHE Italy’s Land of Infinite Discovery the MARCHE region “...For me the Marche is the East, the Orient, the sun that comes at dawn, the light in Urbino in Summer...” Discovering Mario Luzi (Poet, 1914-2005) Overlooking the Adriatic Sea in the centre of Italy, with slightly more than a million and a half inhabitants spread among its five provinces of Ancona, the regional seat, Pesaro and Urbino, Macerata, Fermo and Ascoli Piceno, with just one in four of its municipalities containing more than five thousand residents, the Marche, which has always been Italyʼs “Gateway to the East”, is the countryʼs only region with a plural name. Featuring the mountains of the Apennine chain, which gently slope towards the sea along parallel val- leys, the region is set apart by its rare beauty and noteworthy figures such as Giacomo Leopardi, Raphael, Giovan Battista Pergolesi, Gioachino Rossini, Gaspare Spontini, Father Matteo Ricci and Frederick II, all of whom were born here. This guidebook is meant to acquaint tourists of the third millennium with the most important features of our terri- tory, convincing them to come and visit Marche. Discovering the Marche means taking a path in search of beauty; discovering the Marche means getting to know a land of excellence, close at hand and just waiting to be enjoyed. Discovering the Marche means discovering a region where both culture and the environment are very much a part of the Made in Marche brand. 3 GEOGRAPHY On one side the Apen nines, THE CLIMATE od for beach tourism is July on the other the Adriatic The regionʼs climate is as and August. -

La Vestale Gaspare Spontini

La Vestale Gaspare Spontini NOUVELLE PRODUCTION Jérémie Rhorer direction Eric Lacascade mise en scène DU 15 AU 28 OCTOBRE 2013 6 REPRESENTATIONS Théâtre des Champs-Elysées SERVICE DE PRESSE +33 1 49 52 50 70 theatrechampselysees.fr La Caisse des Dépôts soutient l’ensemble de la RESERVATIONS programmation du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées T. +33 1 49 52 50 50 theatrechampselysees.fr Spontini 5 La Vestale La Vestale Gaspare Spontini NOUVELLE PRODUCTION Jérémie Rhorer direction Eric Lacascade mise en scène Emmanuel Clolus décors Marguerite Bordat costumes Philippe Berthomé lumières Daria Lippi dramaturgie Ermonela Jaho Julia Andrew Richards Licinius Béatrice Uria-Monzon La Grande Vestale Jean-François Borras Cinna Konstantin Gorny Le Souverain Pontife Le Cercle de l’Harmonie Chœur Aedes 160 ans après sa dernière représentation à Paris, le Théâtre des Champs-Elysées présente une nouvelle production de La Vestale de Gaspare Spontini. Spectacle en français Durée de l’ouvrage 2h10 environ Coproduction Théâtre des Champs-Elysées / Théâtre de la Monnaie, Bruxelles MARDI 15, VENDREDI 18, MERCREDI 23, VENDREDI 25, LUNDI 28 OCTOBRE 2013 19 HEURES 30 DIMANCHE 20 OCTOBRE 2013 17 HEURES SERVICE DE PRESSE Aude Haller-Bismuth +33 1 49 52 50 70 / +33 6 48 37 00 93 [email protected] www.theatrechampselysees.fr/presse Spontini 6 Dossier de presse - La Vestale 7 La Vestale La nouvelle production du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées La Vestale n’a pas été représentée à Paris en version scénique depuis 1854. On doit donner encore La Vestale... que je l’entende une seconde fois !... Quelle Le Théâtre des Champs-Elysées a choisi, pour cette nouvelle production, de œuvre ! comme l’amour y est peint !.. -

Professor Niecks on Melodrama Author(S): Frederick Niecks Source: the Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol

Professor Niecks on Melodrama Author(s): Frederick Niecks Source: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 42, No. 696 (Feb. 1, 1901), pp. 96-97 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3366388 . Accessed: 21/12/2014 00:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 00:58:46 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions L - g6 THE MUSICAL TIMES.-FEBRUARY I, I901. of any service is, of course, always undesirable. musical society as well as choir inspectorand con- But it is permissible to remind our young and ductor to the Church Choral Association for the enthusiastic present-day cathedral organists that the Archdeaconryof Coventry. In I898 he became rich store of music left to us by our old English church organistand masterof the choristersof Canterbury composers should not be passed by, even on Festival Cathedral,in succession to Dr. -

Schiller and Music COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Schiller and Music COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Schiller and Music r.m. longyear UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 54 Copyright © 1966 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Longyear, R. M. Schiller and Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469657820_Longyear Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Longyear, R. M. Title: Schiller and music / by R. M. Longyear. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 54. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1966] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 66064498 | isbn 978-1-4696-5781-3 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5782-0 (ebook) Subjects: Schiller, Friedrich, 1759-1805 — Criticism and interpretation. -

The Complete Early Variations

BEETHOVEN THE COMPLETE EARLY VARIATIONS Alessandro Commellato fortepiano Ludwig van Beethoven 1770-1827 1. 32 Variations in C minor 8. 10 Variation in B flat WoO73 14. 8 Variations in C WoO67 WoO80 on an original theme 11’43 on Salieri’s air ‘La stessa on a theme by Count Waldstein 2. 5 Variations in D WoO79 la stessissima’ 12’28 for piano four hands 8’58 on ‘Rule Britannia’ 5’36 9. 8 Variations in C WoO72 on 15. 13 Variations in A WoO66 3. 7 Variations in D WoO78 Grétry’s air ‘Un fievre brûlante’ 7’12 on Dittersdorf’s air ‘Es war on ‘God save the King’ 8’43 10. 12 Variations in A WoO71 on a einmal ein alter Mann’ 14’55 4. 6 Easy Variations in G WoO77 Russian Dance from Wranitsky’s 16. 24 Variations in D WoO65 on an original theme 7’27 ballet ‘Das Waldmädchen’ 12’20 on Righini’s air ‘Venni amore’ 23’29 5. 8 Variations in F WoO76 11. 6 Variations in G WoO70 17. 6 Easy Variations in F WoO64 from Süssmayr’s theme on Paisiello's air on a Swiss air 2’57 ‘Tändeln und Scherzen’ 9’21 ‘Nel cor più non mi sento’ 5’45 18. 9 Variations in C minor WoO63 6. 7 Variations in F WoO75 12. 9 Variations in A WoO69 on on a march by Dressler 12’41 from Winter’s opera ‘Das Paisiello’s air ‘Quant’è più bello’ 6’07 unterbrochene Opferfest’ 11’54 13. 12 Variations in C WoO68 Alessandro Commellato fortepiano 7. -

Download This Volume In

Sederi 29 2019 IN MEMORIAM MARÍA LUISA DAÑOBEITIA FERNÁNDEZ EDITOR Ana Sáez-Hidalgo MANAGING EDITOR Francisco-José Borge López REVIEW EDITOR María José Mora PRODUCTION EDITORS Sara Medina Calzada Tamara Pérez Fernández Marta Revilla Rivas We are grateful to our collaborators for SEDERI 29: Leticia Álvarez Recio (U. Sevilla, SP) Adriana Bebiano (U. Coimbra, PT) Todd Butler (Washington State U., US) Rui Carvalho (U. Porto, PT) Joan Curbet (U. Autònoma de Barcelona, SP) Anne Valérie Dulac (Sorbonne U., FR) Elizabeth Evenden (U. Oxford, UK) Manuel Gómez Lara (U. Seville, SP) Andrew Hadfield (U. Sussex, UK) Peter C. Herman (San Diego State U., US) Ton Hoensalars (U. Utrecth, NL) Douglas Lanier (U. New Hampshire, US) Zenón Luis Martínez (U. Huelva, SP) Willy Maley (U. Glasgow, UK) Irena R. Makaryk (U. Ottawa, CA) Jaqueline Pearson (U. Manchester, UK) Remedios Perni (U. Alicante, SP) Ángel Luis Pujante (U. Murcia, SP) Miguel Ramalhete Gomes (U. Lisboa, PT) Katherine Romack (U. West Florida, US) Mary Beth Rose (U. Illinois at Chicago, US) Jonathan Sell (U. Alcalá de Henares, SP) Alison Shell (U. College London, UK) Erin Sullivan (Shakespeare Institute, U. Birmingham, UK) Sonia Villegas (U. Huelva, SP) Lisa Walters (Liverpool Hope U., UK) J. Christopher Warner (Le Moyne College, US) Martin Wiggins (Shakespeare Institute, U. Birmingham, UK) R. F. Yeager (U. West Florida, US) Andrew Zurcher (U. Cambridge, UK) Sederi 29 (2019) Table of contents María Luisa Dañobeitia Fernández. In memoriam By Jesús López-Peláez Casellas ....................................................................... 5–8 Articles Manel Bellmunt-Serrano Leskov’s rewriting of Lady Macbeth and the processes of adaptation and appropriation .......................................................................................................... -

Shakespeare Y Roméo Et Julieite De Charles Gounod

SHAKESPEARE Y ROMÉO ET JULIEITE DE CHARLES GOUNOD Por RAMÓN MARÍA SERRERA "Shakespeare aplastó con su genio, con su dinámica propia, a casi todos los compositores que trataron de transformar sus dramas en óperas" (Alejo Carpentier) No podía ser de otra forma. Cuando baja el telón al final de la representación, los dos amantes yacen muertos sobre el es cenario. Él, tras ingerir el veneno, después de creer que su amada Julieta ha bebido una pócima mortal. Ella, autoinrnolándose por amor cuando descubre que Romeo ha puesto fin a su vida. Una vez más, corno en toda auténtica ópera romántica, un destino ab surdo, pero inexorable, impide a los protagonistas hallar la felici dad, la paz o la consumación de su amor en este mundo. Porque el amor romántico es -no lo olvidemos- un amor siempre imposi ble, un amor que se vive desde el sufrimiento y que se enfrenta a barreras y convenciones sociales, étnicas, políticas o familiares siempre infranqueables. En el Romanticismo la felicidad está cla ramente desacreditada. Deben sufrir hasta el límite, hasta poner fin a sus vidas, estos jóvenes amantes protagonistas de una histo ria de amor irrealizable a causa de rivalidades familiares o de clanes: capuletos y montescos, güelfos y gibelinos, zegríes y aben cerrajes ... Lo mismo da. De lo contrario, no serían los personajes principales de una historia de amor romántica. Y Shakespeare fue un gran dramaturgo romántico ... 136 RAMÓN MARÍA SERRERA - SHAKESPEARE Y EL MELODRAMA ROMÁNTICO En su autobiografía Gounod dejó escrito que "para un com positor, no hay sino un camino a seguir para hacerse de un nombre, y éste es el teatro, la ópera. -

THE REAL THING?1 ADAPTATIONS, TRANSFORMATIONS and BURLESQUES of SHAKESPEARE, HISTORIC and POST-MODERN the Practice of Adapting G

The real thing? Adaptations, transformations... 289 THE REAL THING?1 ADAPTATIONS, TRANSFORMATIONS AND BURLESQUES OF SHAKESPEARE, HISTORIC AND POST-MODERN Manfred Draudt University of Austria The practice of adapting great authors to fit current requirements is not just a recent phenomenon. The first great wave of adaptations of Shakespeare came after the period of the closing of theatres in 1642, with the advent of the Restoration in 1660. Political change was accompanied by a radical change in tastes, ideals and conditions: theatres were roofed in and artificially illuminated (like the earlier private theatres); there was also elaborate changeable scenery; and for the first time female roles were taken by professional actresses. Most importantly, French neo-classicism was adopted as the fashionable theory that shaped both the form and the language of plays. These currents of change motivated playwrights and managers to “improve on” Shakespeare by rewriting and staging his plays in accordance with the spirit of the new times. Of the hundreds of adaptations written between 1660 and the end of the eighteenth century2 I want to recall here just a few: William Davenant, born in 1606 and claiming to be Shakespeare’s “natural” or illegitimate son, appears to have started the trend in 1662 with his play Ilha do Desterro Florianópolis nº 49 p. 289-314 jul./dez. 2005 290 Manfred Draudt The Law Against Lovers, in which he combined Much Ado About Nothing with a purified Measure for Measure. Even more popular was his spectacular operatic version of a tragedy: Macbeth. With all the Alterations, Amendments, Additions, and New Songs (1663), followed in 1667 by The Tempest, or the Enchanted Island, in which a male counterpart to Miranda, sisters to her and to Caliban, as well as a female companion to Ariel are added. -

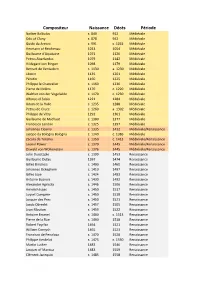

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

German Nationalism and the Allegorical Female in Karl Friedrich Schinkel's the Hall of Stars

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2012-04-17 German Nationalism and the Allegorical Female in Karl Friedrich Schinkel's The Hall of Stars Allison Slingting Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Slingting, Allison, "German Nationalism and the Allegorical Female in Karl Friedrich Schinkel's The Hall of Stars" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 3170. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3170 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. German Nationalism and the Allegorical Female in Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s The Hall of Stars Allison Sligting Mays A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Heather Belnap Jensen, Chair Robert B. McFarland Martha Moffitt Peacock Department of Visual Arts Brigham Young University August 2012 Copyright © 2012 Allison Sligting Mays All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT German Nationalism and the Allegorical Female in Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s The Hall of Stars Allison Sligting Mays Department of Visual Arts, BYU Master of Arts In this thesis I consider Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s The Hall of Stars in the Palace of the Queen of the Night (1813), a set design of Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), in relation to female audiences during a time of Germanic nationalism.