Jean-Philippe Rameau — Georg Anton Benda PYGMALION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

103 the Music Library of the Warsaw Theatre in The

A. ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA, MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW..., ARMUD6 47/1-2 (2016) 103-116 103 THE MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW THEATRE IN THE YEARS 1788 AND 1797: AN EXPRESSION OF THE MIGRATION OF EUROPEAN REPERTOIRE ALINA ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA UDK / UDC: 78.089.62”17”WARSAW University of Warsaw, Institute of Musicology, Izvorni znanstveni rad / Research Paper ul. Krakowskie Przedmieście 32, Primljeno / Received: 31. 8. 2016. 00-325 WARSAW, Poland Prihvaćeno / Accepted: 29. 9. 2016. Abstract In the Polish–Lithuanian Common- number of works is impressive: it included 245 wealth’s fi rst public theatre, operating in War- staged Italian, French, German, and Polish saw during the reign of Stanislaus Augustus operas and a further 61 operas listed in the cata- Poniatowski, numerous stage works were logues, as well as 106 documented ballets and perform ed in the years 1765-1767 and 1774-1794: another 47 catalogued ones. Amongst operas, Italian, French, German, and Polish operas as Italian ones were most popular with 102 docu- well ballets, while public concerts, organised at mented and 20 archived titles (totalling 122 the Warsaw theatre from the mid-1770s, featured works), followed by Polish (including transla- dozens of instrumental works including sym- tions of foreign works) with 58 and 1 titles phonies, overtures, concertos, variations as well respectively; French with 44 and 34 (totalling 78 as vocal-instrumental works - oratorios, opera compositions), and German operas with 41 and arias and ensembles, cantatas, and so forth. The 6 works, respectively. author analyses the manuscript catalogues of those scores (sheet music did not survive) held Keywords: music library, Warsaw, 18th at the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych in War- century, Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, saw (Pl-Wagad), in the Archive of Prince Joseph musical repertoire, musical theatre, music mi- Poniatowski and Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz- gration Poniatowska. -

La Cultura Italiana

LA CULTURA ITALIANA BALDASSARE GALUPPI (1706–1785) Thousands of English-speaking students are only familiar with this composer through a poem by Robert Browning entitled “A Toccata of Galuppi’s.” Few of these students had an inkling of who he was or had ever heard a note of his music. This is in keeping with the poem in which the toccata stands as a symbol of a vanished world. Although he was famous throughout his life and died a very rich man, soon after his death he was almost entirely forgotten until Browning resurrected his name (and memory) in his 1855 poem. He belonged to a generation of composers that included Christoph Willibald Gluck, Domenico Scarlatti, and CPE Bach, whose works were emblematic of the prevailing galant style that developed in Europe throughout the 18th century. In his early career he made a modest success in opera seria (serious opera), but from the 1740s, together with the playwright and librettist Carlo Goldoni, he became famous throughout Europe for his opera buffa (comic opera) in the new dramma giocoso (playful drama) style. To the suc- ceeding generation of composers he became known as “the father of comic opera,” although some of his mature opera seria were also widely popular. BALDASSARE GALUPPI was born on the island of Burano in the Venetian Lagoon on October 18, 1706, and from as early as age 22 was known as “Il Buranello,” a nickname which even appears in the signature on his music manuscripts, “Baldassare Galuppi, detto ‘Buranello’ (Baldassare Galuppi, called ‘Buranello’).” His father was a bar- ber, who also played the violin in theater orchestras, and is believed to have been his son’s first music teacher. -

Table 7-1 French Opera Repertory 1753–62

1 Table 12-1 French Opera Repertory 1753–63 (with Court performances of opéras- comiques in 1761–63) See Table 1-1 for the period 1742–52. This Table is an overview of commissions and revivals in the elite institutions of French opera. Académie Royale de Musique and Court premieres are listed separately for each work (albeit information is sometimes incomplete). The left-hand column includes both absolute world premieres and important earlier works new to these theatres. Works given across a New Year period are listed twice. Individual entrées are mentioned only when revived separately, or to avoid ambiguity. Prologues are mostly ignored. Sources: BrennerD, KaehlerO, LagraveTP, LajarteO, Lavallière, Mercure, NG, RiceFB, SerreARM. Italian works follow name forms etc. cited in Parisian libretti. LEGEND: ARM = Académie Royale de Musique (Paris Opéra); bal. = ballet; bouf. = bouffon; CI = Comédie-Italienne; cmda = comédie mêlée d’ariettes; com. lyr. = comédie lyrique; d. gioc.= dramma giocoso; div. scen. = divertimento scenico; FB = Fontainebleau; FSG = Foire Saint-Germain; FSL = Foire Saint-Laurent; hér. = héroïque; int. = intermezzo; NG = The New Grove Dictionary of Music; NGO = The New Grove Dictionary of Opera; op. = opéra; p. = pastorale; Vers. = Versailles; < = extract from; R = revised. 1753 ALL AT ARM EXCEPT WHERE MARKED Premieres at ARM (listed first) and Court Revivals at ARM or Court (by original date) Titon & l’Aurore (p. hér., 3: La Marre, Voisenon, Atys (Lully, 1676) FB La Motte / Mondonville, Jan. 9) Phaëton (Lully, 1683) Scaltra governatrice, La (d. gioc., 3: Palomba / Fêtes Grecques et romaines, Les (Blamont, 1723) Cocchi, Jan. 25) Danse, La (<Fêtes d’Hébé, Les)(Rameau, 1739) FB Jaloux corrigé, Le (op. -

Professor Niecks on Melodrama Author(S): Frederick Niecks Source: the Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol

Professor Niecks on Melodrama Author(s): Frederick Niecks Source: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 42, No. 696 (Feb. 1, 1901), pp. 96-97 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3366388 . Accessed: 21/12/2014 00:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 00:58:46 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions L - g6 THE MUSICAL TIMES.-FEBRUARY I, I901. of any service is, of course, always undesirable. musical society as well as choir inspectorand con- But it is permissible to remind our young and ductor to the Church Choral Association for the enthusiastic present-day cathedral organists that the Archdeaconryof Coventry. In I898 he became rich store of music left to us by our old English church organistand masterof the choristersof Canterbury composers should not be passed by, even on Festival Cathedral,in succession to Dr. -

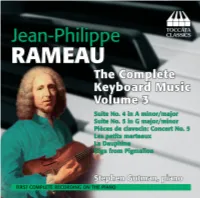

Toccata Classics TOCC0052 Notes

RAMEAU ON THE PIANO, VOLUME THREE 1 by Graham Sadler The two suites recorded on this disc are from the Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin of 1729 or 1730, Rameau’s final collection of solo keyboard music.2 Like those of his Pièces de clavessin (1724), they are contrasted both in tonality and character. The Suite in A minor and major is dominated by dances and includes only three character pieces, whereas the Suite in G major and minor consists almost exclusively of pieces with character titles. In its make-up if not its style, the latter thus follows the example of François Couperin, whose first three books of pièces de clavecin (1713, 1717 and 1722) had established the vogue for descriptive pieces. In that sense, Rameau may be regarded as somewhat conservative in devoting half of his two mature solo collections to suites of the more traditional type. Suite No. 4 in A minor and major Conservative they may be, but the dance movements of the Nouvelles suites are among the most highly P developed in the repertory, the first two particularly so. The Allemande 1 unfolds with an effortless grace, its unerring sense of direction reinforced by the many sequential passages. At the end of both sections, the duple semiquaver motion gives way unexpectedly to triplet motion, providing a memorable ‘rhyme’ to the two parts of the movement. The Courante 2, more than twice as long as its predecessors in Rameau’s output, displays a technical sophistication without parallel in the clavecin repertory. Three themes interlock in mainly three- part counterpoint – a bold motif in rising fourths, and two accompanying figures in continuous quavers, the one in sinuous stepwise movement, the other comprising cascading arpeggios. -

Schiller and Music COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Schiller and Music COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Schiller and Music r.m. longyear UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 54 Copyright © 1966 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Longyear, R. M. Schiller and Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469657820_Longyear Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Longyear, R. M. Title: Schiller and music / by R. M. Longyear. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 54. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1966] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 66064498 | isbn 978-1-4696-5781-3 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5782-0 (ebook) Subjects: Schiller, Friedrich, 1759-1805 — Criticism and interpretation. -

„A TRIBUTE to FAUSTINA BORDONI“ SONY-Release Spring 2012 Ouvertüren & Arien Von G

Christoph Müller & Stefan Pavlik artistic management GmbH Byfangweg 22 CH 4051 Basel T: +41 61 273 70 10 F: +41 61 273 70 20 [email protected] www.artisticmanagement.eu Tribute to Faustina Bordoni Cappella Gabetta Andrés Gabetta - Violine und Leitung Gabor Boldoczki - Trompete Sergei Nakariakov – Trompete Tournee auf Anfrage „A TRIBUTE TO FAUSTINA BORDONI“ SONY-Release spring 2012 Ouvertüren & Arien von G. F. Händel und J. A. Hasse Müller & Pavlik artistic management GmbH Vivica Genaux, Mezzosopran Cappella Gabetta, Andrés Gabetta, Konzertmeister JOHANN ADOLPH HASSE (1699-1783) Ouvertüre aus »Zenobia« (1740/1761) JOHANN ADOLPH HASSE Recitativo e aria: "Son morta... Nelle cupe orrende grotte aus »Senocrita« (1737) JOHANN ADOLPH HASSE Ouvertüre aus »Il ciro riconosciuto« (1748) Aria: "Quel nome se ascolto"aus »Il Ciro riconosciuto« Aria "Padre ingiusto" aus »Cajo Fabricio« (1734) GEORG FRIEDRICH HÄNDEL (1685 – 1759) Ouvertüre aus »Poro, re dell’Indie» HWV 28 (1731) Aria: "Ti pentirai, crudel" aus »Tolomeo« HWV 25 (1728) Pause GEORG FRIEDRICH HÄNDEL Müller & Pavlik Artistic Management GmbH Ouvertüre aus »Arminio« HWV 36 (1736) GEORG FRIEDRICH HÄNDEL Aria: "Lusinghe più care" aus »Alessandro« HWV 21 (1726) Aria: "Parmi che giunta in porto" aus »Radamisto« HWV 12 (1720) JOHANN ADOLPH HASSE Ouvertüre aus »Didone abbandonata« (1742) Aria "Ah! che mancar mi sento" (1781) Aria: "Qual di voi... Piange quel fonte" aus »Numa Pompilio« (1741) JOHANN ADOLPH HASSE Aria: "Va' tra le selve ircane" aus »Artaserse« (1730) Faustina Bordoni, Primadonna assoluta der Dresdner Hofoper und Frau von J. A. Hasse. Starb 1781. „Ah! Che mancar mi sento“ schrieb Hasse wenige Tage nach ihrem Tod. Cappella Gabetta Sol Gabetta erfüllte sich mit der "Cappella Gabet- ta" einen ihrer musikalischen Träume: Mit ihrem Bruder Andrès Gabetta als Konzert- meister und einer handverlesenen Schar von hoch qualifizierten Musikern aus Gabettas Umfeld kre- ieren sie Programme aus Barock und Frühklassik, die sie auf Originalinstrumenten in Konzerten und auf CD präsentieren. -

Cpo 555 156 2 Booklet.Indd 1 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Jean-Philippe Rameau

Jean-Philippe Rameau Pigmalion · Dardanus Suites & Arias Anders J. Dahlin L’Orfeo Barockorchester Michi Gaigg cpo 555 156_2 Booklet.indd 1 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Jean-Philippe Rameau cpo 555 156_2 Booklet.indd 2 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) Pigmalion Acte-de-ballet, 1748 Livret by Sylvain Ballot de Sauvot (1703–60), after ‘La Sculpture’ from Le Triomphe des arts (1700) by Houdar de la Motte (1672–1731) (selected movements: Suite & Arias) 1 Ouverture 4'41 2 [Air,] ‘Fatal Amour’ (Pigmalion) 3'22 3 Air. Très lent – Gavotte gracieuse – Menuet – Gavotte gai – Chaconne vive – 5'44 Loure – Passepied vif – Rigaudon vif – Sarabande pour la Statue – Tambourin 4 Air gai 2'19 5 Pantomime niaise 0'44 6 2e Pantomime très vive 2'07 7 Ariette, ‘Règne Amour’ (Pigmalion) 4'35 8 Air pour les Graces, Jeux et Ris 0'50 9 Rondeau Contredanse 1'37 cpo 555 156_2 Booklet.indd 3 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Dardanus Tragedie en musique, 1739 (rev. 1744, 1760) Livret by Charles-Antoine Leclerc de La Bruère (1716–54) (selected movements: Suite & Arias) 10 Ouverture 4'13 11 Prologue, sc. 1: Air pour les [Jeux et les] Plaisirs [et la Jalousie et sa Suite] 1'06 12 Air pour les [Jeux et les] Plaisirs 1'05 13 Prologue, sc. 2: Air gracieux [pour les Peuples de différentes nations] 1'30 14 Rigaudon 1'41 15 Act 1, sc. 3: Air vif 2'46 16 Rigaudons 1 et 2 3'36 17 Act 2, sc. 1: Ritournelle vive 1'08 18 Act 4, sc. -

2017-2018 Sweet Philomela

! NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Handel composed his ode L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato in 1740, as English-language works finally replaced Italian operas once and for all in English theaters (though a preference for Italian titles lingered). Not properly speaking an oratorio, this grandiose ode—more a poetic than musical category—is a dialogue between the extrovert and introvert in all of us. Its inspired libretto incorporates two John Milton poems, L’Allegro (Mirth) and Il Penseroso (Melancholy), plus Charles Jennen’s Il Moderato (Moderation), itself an homage to Milton. Though Milton’s poetry was then over 100 years old, its wide range of quintessential English imagery—from lovely pastoral scenes to stirring cathedral music—still held great sway over Handel’s audiences. Among this ode’s most fetching movements are several that evoke sounds from nature: the warbling of the nightingale, for example, features prominently in “Sweet Bird.” Our opening set, which mixes various solos from this work with Handel concerto movements, is a kind of miniaturization of the composer’s own practice: the first performance of L’Allegro in February 1740 included two of his Op. 6 concerti as intermission features. Just two decades later, Benjamin Franklin enchanted London audiences with his latest invention: the glass harmonica. This instrument mechanized the familiar practice of rubbing rims of glasses filled with varying amounts of water, thereby producing a strange, unearthly resonance. Franklin’s wondrous machine operates by means of glass bowls of varying sizes nested horizontally on a spindle, rotated steadily by a foot treadle (like a spinning wheel), and played by applying wet fingers to their rims. -

A European Singspiel

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2012 Die Zauberflöte: A urE opean Singspiel Zachary Bryant Columbus State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Zachary, "Die Zauberflöte: A urE opean Singspiel" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 116. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. r DIE ZAUBEFL5TE: A EUROPEAN SINGSPIEL Zachary Bryant Die Zauberflote: A European Singspiel by Zachary Bryant A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program for Honors in the Bachelor of Arts in Music College of the Arts Columbus State University Thesis Advisor JfAAlj LtKMrkZny Date TttZfQjQ/Aj Committee Member /1^^^^^^^C^ZL^>>^AUJJ^AJ (?YUI£^"QdJu**)^-) Date ^- /-/<£ Director, Honors Program^fSs^^/O ^J- 7^—^ Date W3//±- Through modern-day globalization, the cultures of the world are shared on a daily basis and are integrated into the lives of nearly every person. This reality seems to go unnoticed by most, but the fact remains that many individuals and their societies have formed a cultural identity from the combination of many foreign influences. Such a multicultural identity can be seen particularly in music. Composers, artists, and performers alike frequently seek to incorporate separate elements of style in their own identity. One of the earliest examples of this tradition is the German Singspiel. -

The Greatest Opera Never Written: Bengt Lidner's Medea (1784)

Western Washington University Masthead Logo Western CEDAR Music Faculty and Staff ubP lications Music 2006 The Greatest Opera Never Written: Bengt Lidner’s Medea (1784) Bertil Van Boer Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/music_facpubs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Boer, Bertil, "The Greatest Opera Never Written: Bengt Lidner’s Medea (1784)" (2006). Music Faculty and Staff Publications. 3. https://cedar.wwu.edu/music_facpubs/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Faculty and Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bertil van Boer The Greatest Opera Never Written: Bengt Lidner’s Medea (1784) hen the Gustavian opera was inaugurated on 18 January 1773 with a performance of Johan Wellander and Fran- W cesco Antonio Baldassare Uttini’s Thetis och Pelée, the an- ticipation of the new cultural establishment was palpable among the audiences in the Swedish capital. In less than a year, the new king, Gustav III, had turned the entire leadership of the kingdom topsy-turvy through his bloodless coup d’état, and in the consolida- tion of his rulership, he had embarked upon a bold, even politically risky venture, the creation of a state-sponsored public opera that was to reflect a new cultural nationalism, with which he hoped to imbue the citizenry with an understanding of the special role he hoped they would play in the years to come.