A Brief History of Beacon Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unitarian Universalist Association Annual Report June 2008

Unitarian Universalist Association Annual Report June 2008 William G. Sinkford-President Kathleen Montgomery-Executive Vice President 1 INTRODUCTION The Association’s mission for the staff is to: 1. Support the health and vitality of Unitarian Universalist congregations as they minister in their communities. 2. Open the doors of Unitarian Universalism to people who yearn for liberal religious community. 3. Be a respected voice for liberal religious values. This report outlines for you, by staff group, the work that has been done on your behalf this year by the staff of the Unitarian Universalist Association. It comes with great appreciation for their extraordinary work in a time of many new initiatives in response to the needs of our faith and our congregations. If you have questions in response to the information contained here, please feel free to contact Kay Montgomery ([email protected]). William G. Sinkford, President Kathleen Montgomery, Executive Vice President 2 CONTENTS STAFF GROUPS: Advocacy and Witness Page 4 Congregational Services Page 6 District Services Page 13 Identity Based Ministries Page 15 Lifespan Faith Development Page 16 Ministry and Professional Leadership Page 24 Communications Page 27 Beacon Press Page 31 Stewardship and Development Page 33 Financial Services Page 36 Operations / Facilities Equal Employment Opportunity Report Page 37 3 ADVOCACY AND WITNESS STAFF GROUP The mission of the Advocacy and Witness staff group is to carry Unitarian Universalist values into the wider world by inserting UU perspectives into public debates of the day. Advocacy and Witness staff members work closely in coalitions with other organizations which share our values, as well as local UU congregations, to be effective in this ministry internationally, nationally, and in state and local efforts. -

Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004)

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Department of Professional Studies Studies 2004 Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De- Mythologizing of the American West Jennie A. Harrop George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac Recommended Citation Harrop, Jennie A., "Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004). Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies. Paper 5. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Professional Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGLING FOR REPOSE: WALLACE STEGNER AND THE DE-MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Jennie A. Camp June 2004 Advisor: Dr. Margaret Earley Whitt Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ©Copyright by Jennie A. Camp 2004 All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. GRADUATE STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF DENVER Upon the recommendation of the chairperson of the Department of English this dissertation is hereby accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Profess^inJ charge of dissertation Vice Provost for Graduate Studies / if H Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST CONGREGATION of CASTINE July 8, 2018

UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST CONGREGATION OF CASTINE July 8, 2018 “A Faith That Moves Us Now” "The purpose of the church is to heal the consequences of lovelessness and injustice in the hearts and souls of our members so they might heal the community and together heal the world." ~ Nancy Bowen READING “Saving Unitarian Universalism” ~ John T. Crestwell, Jr. [page 56, Voices from the Margins, An Anthology of Meditations, edited by Jacqui James and Mark D. Morrison-Reed. Boston: Skinner House Books, 2012] The thing that will save our faith, and that will allow us to become better lovers, fathers, mothers, daughters, sons, and friends, is building relationships – learning more about each other – seeing God in all people, places, and things. It’s rooted in experience. The more we learn and grow with liberal minds and hearts, the more we see the Spirit emanating. The more we learn about our common destiny, the more we see that we all come from the same source; that we are all capable of good; that “God don’t make no junk”; that the world we have is the world we’ve collectively created through our thoughts, words, and deeds. And when we see things differently, we can start doing things differently. READING “Love Abundant” ~ Alicia Forde [page 62, Voices from the Margins, An Anthology of Meditations, edited by Jacqui James and Mark D. Morrison-Reed. Boston: Skinner House Books, 2012] I lift my eyes up to the hills from where will my help come? My help comes from Love abundant. my help comes from the hills my help—my help, it comes from ancient Mothers whose hearts beat in mine. -

Exploring Boston's Religious History

Exploring Boston’s Religious History It is impossible to understand Boston without knowing something about its religious past. The city was founded in 1630 by settlers from England, Other Historical Destinations in popularly known as Puritans, Downtown Boston who wished to build a model Christian community. Their “city on a hill,” as Governor Old South Church Granary Burying Ground John Winthrop so memorably 645 Boylston Street Tremont Street, next to Park Street put it, was to be an example to On the corner of Dartmouth and Church, all the world. Central to this Boylston Streets Park Street T Stop goal was the establishment of Copley T Stop Burial Site of Samuel Adams and others independent local churches, in which all members had a voice New North Church (Now Saint Copp’s Hill Burying Ground and worship was simple and Stephen’s) Hull Street participatory. These Puritan 140 Hanover Street Haymarket and North Station T Stops religious ideals, which were Boston’s North End Burial Site of the Mathers later embodied in the Congregational churches, Site of Old North Church King’s Chapel Burying Ground shaped Boston’s early patterns (Second Church) Tremont Street, next to King’s Chapel of settlement and government, 2 North Square Government Center T Stop as well as its conflicts and Burial Site of John Cotton, John Winthrop controversies. Not many John Winthrop's Home Site and others original buildings remain, of Near 60 State Street course, but this tour of Boston’s “old downtown” will take you to sites important to the story of American Congregationalists, to their religious neighbors, and to one (617) 523-0470 of the nation’s oldest and most www.CongregationalLibrary.org intriguing cities. -

Historic Houses of Worship in Boston's Back Bay David R. Bains, Samford

Historic Houses of Worship in Boston’s Back Bay David R. Bains, Samford University Jeanne Halgren Kilde, University of Minnesota 1:00 Leave Hynes Convention Center Walk west (left) on Boylston to Mass. Ave. Turn left on Mass. Ave. Walk 4 blocks 1:10 Arrive First Church of Christ Scientist 2:00 Depart for Trinity Church along reflecting pool and northeast on Huntington Old South Church and Boston Public Library are visible from Copley Square 2:15 Arrive Trinity Church 3:00 Depart for First Lutheran Walk north on Clarendon St. past Trinity Church Rectory (n.e. corner of Newbury and Clarendon) First Baptist Church (s.w. corner of Commonwealth and Clarendon) Turn right on Commonwealth, Turn left on Berkley. First Church is across from First Lutheran 3:15 Arrive First Lutheran 3:50 Depart for Emmanuel Turn left on Berkeley Church of the Covenant is at the corner of Berkley and Newbury Turn left on Newbury 4:00 Arrive Emmanuel Church 4:35 Depart for Convention Center Those wishing to see Arlington Street Church should walk east on Newbury to the end of the block and then one block south on Arlington. Stops are in bold; walk-bys are underlined Eight streets that run north-to-south (perpendicular to the Charles) are In 1857, the bay began to be filled, The ground we are touring was completed by arranged alphabetically from Arlington at the East to Hereford at the West. 1882, the entire bay to near Kenmore Sq. by 1890. The filling eliminated ecologically valuable wetlands but created Boston’s premier Victorian The original city of Boston was located on the Shawmut Peninsula which was neighborhood. -

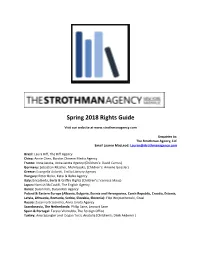

Spring 2018 Rights Guide

Spring 2018 Rights Guide Visit our website at www.strothmanagency.com Enquiries to: The Strothman Agency, LLC Email Lauren MacLeod: [email protected] Brazil: Laura Riff, The Riff Agency China: Annie Chen, Bardon Chinese Media Agency France: Anna Jarota, Anna Jarota Agency (Children’s: David Camus) Germany: Sebastian Ritscher, Mohrbooks, (Children’s: Annelie Geissler) Greece: Evangelia Avloniti, Ersilia Literary Agency Hungary: Peter Bolza, Katai & Bolza Agency Italy: Erica Berla, Berla & Griffini Rights (Children’s: Vanessa Maus) Japan: Hamish McCaskill, The English Agency Korea: Duran Kim, Duran Kim Agency Poland & Eastern Europe (Albania, Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Czech Republic, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia): Filip Wojciechowski, Graal Russia: Zuzanna Brzezinska, Anna Jarota Agency Scandanavia, The Netherlands: Philip Sane, Lennart Sane Spain & Portugal: Teresa Vilarrubla, The Foreign Office Turkey: Amy Spangler and Dogan Terzi, Anatolia (Children's: Dilek Akdemir ) Early Warning: Upcoming & Recently Sold Ruth Ben-Ghiat: Strongmen: How They Rise, Why They Succeed, When They Fall ……………………3 Kathryn Miles: Killers on the Trail: Love, Murder, and the Quest for Justice in America's Wild Places ………………………….……………………………………………………………………..……..…………………………..…4 Michelle Wilde Anderson: Left for Dead: Local Government in the Post-Industrial Age ……..………5 Richard Ford: Dress Codes: Laws of Attire and Crime of Fashion ………………………….……………………6 Now Available: Adult Titles David Kertzer: The Pope Who -

IN THIS ISSUE UUA Bookstore Has a New Name Thrive Youth

Monthly eNews from UUA Stewardship and Development e-newsletter February 2, 2016 IN THIS ISSUE UUA Bookstore Has a New Name Thrive Youth Applications Open Is Your Congregation on the #BlackLivesMatter Map? UU Reads: The Third Reconstruction Donor Feature: Steven Ballesteros Register Now — UU-UNO Spring Seminar A Turning Point for Unitarian Universalism UUA Bookstore Has a New Name The UUA Bookstore wants to share the good news of Unitarian Universalim with a wider audience and has changed its name to inSpirit: UU Book and Gift Shop. The word "inspirit" is rich in meaning. It can mean to fill with spirit, to encourage, to exhilarate, or to bestow with strength or purpose. The new name reflects the many ways inSpirit serves UUs, our congregations, and our communities. inSpirit offers a wide range of books and gifts that reflect the values of our UU movement, including titles from Skinner House Books and Beacon Press, selected titles from other publishers, and fair trade gift and clothing items. inSpirit will continue to bring in new merchandise and reading materials to attract a wide, progressive audience online and to the Boston storefront. Thrive Youth Applications Open Thrive Youth Applications are now open. Thanks to your generosity, Unitarian Universalist Youth of Color will come together for a five-day gathering to deepen their faith, lift their spirits, and build critical skills for leadership in the face of our broken, yet beautiful world. Thrive participants will be guided by experienced facilitators as they worship together, play, explore their racial and ethnic identities, develop leadership skills, and create supportive community. -

Unitarian Universalism Selected Essays 2001

Unitarian Universalism Selected Essays 2001 Published by the Unitarian Universalist Ministers’ Association Boston, Massachusetts The Reverend Craig Roshaven, Publications Repres e n t a t i v e Kristen B. Payson, editorial consultant Unitarian Universalism Selected Essays 2001 Preface . v Berry Street Lecture 2000 . .1 The Rev. Dr. Mark D. Morrison-Reed Fahs Lecture 2000 Queer(y)ing Religious Education: Teaching the R(evolutionary) S(ub)-V(ersions)! or Relax! … It’s Just Religious Ed . .13 The Rev. Elias Farajaje-Jones An Awakened, Compassionate Life in Today’s World . .39 Barbara Carlson Does a Building Matter? An Inquiry into the Effectiveness of Unitarian Universalist Church Architecture . .51 Charlotte Shivers The Law and the Spirit: Power, Sexuality, and Ministry . .67 The Rev. Sylvia Howe & The Rev. Paul L’Herrou A Theology of Power in the Ministry . .81 The Rev. Gordon B. McKeeman The Core of Unitarian Universalism . .91 Charles A. Howe ii UUMA Selected Essays — 2001 2001 — UUMA Selected Essays iii Preface This volume of essays is the creative product of many Unitarian Universalist colleagues who have challenged themselves to reflect at length on issues of impor- tance to our ministry. This year, six essays were submitted to a four-member panel of peers for rev i e w . Five were selected for publication. Most, though not all, of these essays were first presented to Unitarian Universalist gatherings or study gro u p s . In the future, we will continue to consider well-written essays of relevance and in t e r est to our ministry for publication, even if they have not been presented to a Unitarian Universalist gathering or study grou p . -

What Is Marriage For? a LEADER’S GUIDE

What Is Marriage For? A LEADER’S GUIDE Adapted from At Issue: Marriage, Exploring the Debate over Marriage Rights for Same-Sex Couples Leader’s Guide, by Scott Hirschfeld ISBN 0-8070-9143-X CONTENTS Introduction 2 Getting Started 3 SESSION I 5 Part 1: Defining Marriage and Its Purpose Part 2: Evolving Understandings of Marriage SESSION II 7 Part 1: Modern Understandings of Marriage Part 2: Attitudes toward Same-Sex Marriage Part 3: Revisiting Our Definitions Further Reading/Acknowledgments APPENDIX 10 Handout 1 Evolving Understandings of Marriage Handout 2 Evolving Understandings of Marriage (Chart) Handout 3 Modern Understandings of Marriage Handout 4 Participant Evaluation Form Leader Evaluation Form What Is Marriage For?: The Strange Social History of our Most Intimate Institution by E.J. Graff Beacon Press, 1999/$15.00/paperback/0-8070-4115-7 UUA Bookstore: 1-800-215-9076 or www.uua.org This guide was adapted from At Issue: Marriage, Exploring the Debate over Marriage Rights for Same-Sex Couples, published by the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN). The complete 6-lesson guide is available from the GLSEN Bookstore at www.atlasbooks.com/ glsen or 1-800-247-6553. Introduction In What is Marriage For?: The Strange Social History of our Most Intimate Institution, E.J. Graff describes marriage as “a kind of Jerusalem, an archaeological site on which the present is constantly building over the past, letting history’s many layers twist and tilt into today’s walls and floors.” Indeed, the institution of marriage has changed dramatically over the centuries to reflect evolving understandings of family, money, sex, love and power. -

Beacon Press and the Pentagon Papers

BEACON PRESS AND THE PENTAGON PAPERS Beacon Press 25 Beacon Street Boston, Massachusetts 02108-2892 www.beacon.org Beacon Press books are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations. Grateful acknowledgment is made to Allison Trzop, the author of this history, and to the Unitarian Universalist Veatch Program at Shelter Rock for their generous support of this project. © 2007 by Allison Trzop Originally submitted as a master’s degree project for Emerson College in May 2006 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 10 09 08 07 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the uncoated paper ANSI/NISO specifications for permanence as revised in 1992. Composition by Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services It’s tragic when a nation, dedicated and committed to the principle of freedom, reaches such a point that the greatest fear we have is from the government itself. edwin lane 1971 june 13 The New York Times publishes its first article on the Pentagon Papers under the headline “Vietnam Archive.” june 29–30 Senator Mike Gravel reads from the papers to his Senate subcommittee and enters the rest into its records. The papers are made public. august 17 Beacon Press publicly announces its intention to publish the papers. october 10 The government version of the Pentagon Papers is published. october 22 The Beacon Press edition of the Pentagon Papers is published simultaneously in cloth and paper in four volumes. october 27 FBI agents appear at the New England Merchants National Bank asking to see UUA records. -

Publishers' Introduction

PUBLISHERS' INTRODUCTION. While ve have paid due care and attention to the business department of the enterprise, which now results in a History of Nashua, we have endeavored to neglect nothing which would tend to make it a literary ,tto_,-:---:a *. hstoric value. Me-chanica''y- "IS all that high grade tiaatieria' c..,:, o--a-a h-c' -tte.-t sue a creditable work, can make it.. We thus express our appreciation of the financial support and smpathy of the public through which the production is made possible. We extend our thanks t6 'he :g:entlemen, who without compensation assumed the no light task of preparing their various portions of the work. HISTORY OF THE CITY OF NASHUA, N. H. FRO_M THE EARLIEST SETTLEMENT OF OLD DUNSTABLE TO THE YEAR 1895 WITH BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF EARLY SETTLERS, THEIR DESCENDANTS AND OTHER RESIDENTS [Iluatratcb with flflap, ngraving, aub ortrait PREPARED BV A SELECTED CORPS OF EDITORS UNDER THE BUSINESS SUPERINPENDENCE OF H. REINHEIER & CO. JUDGE EDWARD E. PARKER EDITOR-IN-CHIEF NASHUA, N. H. TELEGRAPH PUBLISHING COMPANY, PUBLISHERS ,I897 Copyright z895, by H. Peinheimer & Co. All rights reserved. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. PAGE. PAGE. Charter of Old Dunstable, Title Page Estabrook.Anderson Shoe Factory (Palm street view) 457 Editorial Group, JEstabrook-Anderson Shoe Factory, 457 The Indian Head House, 64 Estabzook-AndersonShoe Factory (Pine street view) 58 The Arms of the Priory of Dunstable, 77 Nashua Card and Glazed Paper Co. (some of the help) 459 A Venerable Witness, 93 Nashua Card and Glazed Paper Company Factory, -

Unitarian Universalist Theology Renaissance Module ONLINE

Unitarian Universalist Theology Renaissance Module ONLINE VERSION PARTICIPANT GUIDE By Lynn Ungar and Sara Lewis © 2018 by the Faith Development Office of the UUA, Boston, MA Table of Contents About the Authors; Acknowledgement 3 Overview of Sessions 4 Introduction to the Module 6 Pre-Module Assignments 16 Session 1: What Is Theology? 17 Session 2: Early Unitarianism and Universalism 34 Session 3: Expanding Beyond Christian Roots 40 Session 4: More 20th Century Influences 48 Session 5: 21st Century UU Theology 55 Session 6: Closing Session 59 UU Theology Renaissance Module, ONLINE Participant Guide 2 About the Authors Rev. Dr. Lynn Ungar holds an M.Div. from Starr King School for the Ministry and a D. Min. in religious education from McCormick Theological seminary. She has served as a parish minister in Moscow, Idaho and in Chicago, and as a director of religious education in Fremont and Hayward, California. She currently serves as minister for lifespan learning for the Church of the Larger Fellowship, our online UU congregation (www.questformeaning.org and www.clfuu.org ). Lynn is co-author of the Tapestry of Faith curricula Faithful Journeys and Love Connects Us and author of Sing to the Power. Lynn’s poetry can be found in a variety of publications, including her latest book Bread and Other Miracles. She is the composer of the round, “Come, Come, Whoever You Are,” Hymn 188 in Singing the Living Tradition. Sara Lewis, unchurched in her early years, found Unitarian Universalism in her teen years and has served as Director of Religious Education at the Olympia Unitarian Universalist Congregation in Olympia, Washington since 2008.