Play Behaviours and Personality in Juvenile Bornean Orangutans (Pongo Pygmaeus) at an Indonesian Rehabilitation Centre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Animal Law Received Generous Support from the Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Michigan State University College of Law

JOURNAL OF ANIMAL LAW Michigan State University College of Law APRIL 2009 Volume V J O U R N A L O F A N I M A L L A W Vol. V 2009 EDITORIAL BOARD 2008-2009 Editor-in-Chief ANN A BA UMGR A S Managing Editor JENNIFER BUNKER Articles Editor RA CHEL KRISTOL Executive Editor BRITT A NY PEET Notes & Comments Editor JA NE LI Business Editor MEREDITH SH A R P Associate Editors Tabb Y MCLA IN AKISH A TOWNSEND KA TE KUNK A MA RI A GL A NCY ERIC A ARMSTRONG Faculty Advisor DA VID FA VRE J O U R N A L O F A N I M A L L A W Vol. V 2009 Pee R RE VI E W COMMITT ee 2008-2009 TA IMIE L. BRY A NT DA VID CA SSUTO DA VID FA VRE , CH A IR RE B ECC A J. HUSS PETER SA NKOFF STEVEN M. WISE The Journal of Animal Law received generous support from the Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Michigan State University College of Law. Without their generous support, the Journal would not have been able to publish and host its second speaker series. The Journal also is funded by subscription revenues. Subscription requests and article submissions may be sent to: Professor Favre, Journal of Animal Law, Michigan State University College of Law, 368 Law College Building, East Lansing MI 48824. The Journal of Animal Law is published annually by law students at ABA accredited law schools. Membership is open to any law student attending an ABA accredited law college. -

Scientific Briefing on Caged Farming Overview of Scientific Research on Caged Farming of Laying Hens, Sows, Rabbits, Ducks, Geese, Calves and Quail

February 2021 Scientific briefing on caged farming Overview of scientific research on caged farming of laying hens, sows, rabbits, ducks, geese, calves and quail Contents I. Overview .............................................................................................. 4 Space allowances ................................................................................. 4 Other species-specific needs .................................................................... 5 Fearfulness ......................................................................................... 5 Alternative systems ............................................................................... 5 In conclusion ....................................................................................... 7 II. The need to end the use of cages in EU laying hen production .............................. 8 Enriched cages cannot meet the needs of hens ................................................. 8 Space ............................................................................................... 8 Respite areas, escape distances and fearfulness ............................................. 9 Comfort behaviours such as wing flapping .................................................... 9 Perching ........................................................................................... 10 Resources for scratching and pecking ......................................................... 10 Litter for dust bathing .......................................................................... -

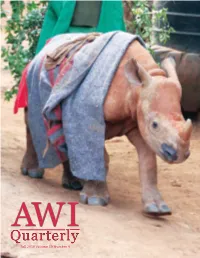

Quarterly Fall 2010 Volume 59 Number 4

AW I Quarterly Fall 2010 Volume 59 Number 4 AWI ABOUT THE COVER Quarterly ANIMAL WELFARE INSTITUTE QUARTERLY Baby black rhinoceros, Maalim, is heading in for his evening bottle and then a good night’s sleep at the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust outside Nairobi. Apparently abandoned by his FOUNDER mother, days-old Maalim (named for the ranger who rescued him) was found in the Ngulia Christine Stevens Rhino Sanctuary and taken to the Trust. Now at 20 months, he has grown quite a bit but is DIRECTORS still just hip-high! Black rhinos, critically endangered with a total wild population believed to Cynthia Wilson, Chair be around 4,200 animals, continue to be poached (along with white rhinos) for their horns. Barbara K. Buchanan “Into Africa” on p. 14 chronicles the visit to the Trust and other Kenyan conservation program John Gleiber sites by AWI’s Cathy Liss. Charles M. Jabbour Mary Lee Jensvold, Ph.D. Photo by Cathy Liss Cathy Liss 4 Michele Walter OFFICERS Cathy Liss, President Cynthia Wilson, Vice President Brutal BLM Roundups Charles M. Jabbour, CPA, Treasurer John Gleiber, Secretary THE UNNECESSARY REMOVAL OF WILD HORSES has reached an alarming rate SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE under the current administration. Thousands of horses have been and continue to Gerard Bertrand, Ph.D. be removed from their native range, and placed in short- and long-term holding Roger Fouts, Ph.D. facilities in the Roger Payne, Ph.D. Midwest. Taxpayers 10 22 Samuel Peacock, M.D. Hope Ryden pay tens of millions Robert Schmidt of dollars a year to John Walsh, M.D. -

Guinea Pigs 79 Group Housing of Males 79 Proper Diet to Prevent Obesity 81 Straw Bedding 83

Caring DiscussionsHands by the Laboratory Animal Refinement & Enrichment Forum Volume II Edited by Viktor Reinhardt Animal Welfare Institute Animal Welfare Institute 900 Pennsylvania Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20003 www.awionline.org Caring Hands Discussions by the Laboratory Animal Refinement & Enrichment Forum, Volume 2 Edited by Viktor Reinhardt Copyright ©2010 Animal Welfare Institute Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-938414-88-9 LCCN 2010910475 Cover photo: Jakub Hlavaty Design: Ava Rinehart and Cameron Creinin Copy editing: Beth Herman, Cathy Liss, Annie Reinhardt and Dave Tilford All papers used in this publication are Acid Free and Elemental Chlorine Free. They also contain 50% recycled content including 30% post consumer waste. All raw materials originate in forests run according to correct principles in full respect for high environmental, social and economic standards at all stages of production. I am dedicating this book to the innocent animal behind bars who has to endure loneliness, boredom and unnecessary distress. Table of Contents Introduction and Acknowledgements i Chapter 1: Basic Issues 2 Annual Usage of Animals in Biomedical Research 4 Cage Space 10 Inanimate Enrichment 16 Enrichment versus Enhancement 17 Behavioral Problems 22 Mood Swings 24 Radio Music/Talk 29 Construction Noise and Vibration Chapter 2: Refinement and Enrichment for Rodents and Rabbits Environmental Enrichment 34 Institutional Standards 35 Foraging Enrichment 36 Investigators’ Permission 38 Rats 40 Amazing Social Creatures 40 Are -

The Legal Guardianship of Animals.Pdf

Edna Cardozo Dias Lawyer, PhD in Law, Legal Consultant and University Professor The Legal Guardianship of Animals Belo Horizonte - Minas Gerais 2020 © 2020 EDNA CARDOZO DIAS Editor Edna Cardozo Dias Final art Aderivaldo Sousa Santos Review Maria Celia Aun Cardozo, Edna The Legal Guardianship of Animals / — Edna Cardozo Dias: Belo Horizonte/Minas Gerais - 2020 - 3ª edition. 346 p. 1. I.Título. Printed in Brazil All rights reserved Requests for this work Internet site shopping: amazon.com.br and amazon.com. Email: [email protected] 2 EDNA CARDOZO DIAS I dedicate this book To the common mother of all beings - the Earth - which contains the essence of all that lives, which feeds us from all joys, in the hope that this work may inaugurate a new era, marked by a firm purpose to restore the animal’s dignity, and the human being commitment with an ethic of life. THE LEGAL GUARDIANSHIP OF A NIMALS 3 Appreciate Professor Arthur Diniz, advisor of my doctoral thesis, defended at the Federal University of Minas Gerais - UFMG, which was the first thesis on animal law in Brazil in February 2000, introducing this new branch of law in the academic and scientific world, starting the elaboration of a “Animal Rights Theory”. 4 EDNA CARDOZO DIAS Sumário Chapter 1 - PHILOSOPHY AND ANIMALS .................................................. 15 1.1 The Greeks 1.1.1 The Pre-Socratic 1.1.2 The Sophists 1.1.3 The Socratic Philosophy 1.1.4 Plato 1.1.5 Peripathetism 1.1.6 Epicureanism 1.1.7 The Stoic Philosophy 1.2 The Biblical View - The Saints and the Animals 1.2.1 St. -

Animal Welfare Law - 2019

ANIMAL WELFARE LAW - 2019 Delcianna J. Winders, Dr. Heather Rally, Donald C. Baur Vermont Law School, Summer Session Term 3 July 8 – 18, 2019 1:00 pm – 4:00 pm SYLLABUS Required Text: Supplemental Materials, available online and by request at the Bookstore Recommended Reading: On reserve in Library or URLs1 Office Hours: 4:30-5:30 p.m., Mondays - Thursdays Exam: Open-book, take-home, anonymous grading, due 3:00 pm, July 21 Required Reading: Advance reading required for first class Volunteer Students: Requested to brief cases marked by an asterisk Week One: July 8 - 11 CLASS I: Monday, July 8: Course Introduction: Overview Animal Ethics and the Pursuit of Enhanced Welfare Required Reading: ______ Ruth Payne (2002), Animal Welfare, Animal Rights, and the Path to Social Reform: One Movement's Struggle for Coherency in the Quest for Change, 9 Va. J. Soc. Pol'y & L. 587. ______ Gary Francione (2010), Animal Welfare and the Moral Value of Nonhuman Animals. Law, Culture, and the Humanities, January 2010, Volume 6, Issue 1, pp 24 – 36. Recommended Reading: Peter Singer, Animal Liberation, (1975). Tom Regan, The Case for Animal Rights, (1983). 1 RR is not necessary for the class. These materials provide additional information and legal authority for the issues discussed in the corresponding class. 144497873.4 CLASS II: Tuesday, July 9: The Captive Animal Condition, Sentience, and Cognition Mandatory Hot Topics Lecture/Brown Bag Lunch: July 9, noon-1 p.m., Confronting America’s Captive Tiger Crisis, Oakes Hall, Room 012 Required Reading: ______ David Fraser, Animal Ethics and Animal Behavior Science: Bridging the Two Cultures, Applied Animal Behaviour Science. -

AWI 2018 Annual Report

Animal Welfare Institute 67th Annual Report July 1, 2017 – June 30, 2018 Who We Are Since 1951, the Animal Welfare Institute (AWI), a nonprofit charitable organization, has been alleviating suffering inflicted on animals by humans. Our Aims Through engagement with policymakers, scientists, industry, and the public, AWI seeks to abolish factory farms, support high- preserve species threatened with extinction, p welfare family farms, and eliminate p and protect wildlife from harmful exploitation inhumane slaughter methods for animals and destruction of critical habitat; raised for food; protect companion animals from cruelty and end the use of steel-jaw leghold traps and p violence, including suffering associated with p reform other brutal methods of capturing inhumane conditions in the pet industry; and and killing wildlife; prevent injury and death of animals caused improve the housing and handling of animals p by harsh transport conditions. p in research, and encourage the development and implementation of alternatives to experimentation on live animals; Table of Contents WILDLIFE 2 e COMPANION ANIMALS 6 e ANIMALS IN LABORATORIES 10 e FARM ANIMALS 14 e HUMANE EDUCATION 18 e MARINE ANIMALS 20 e GOVERNMENT AFFAIRS 24 e AWI QUARTERLY 28 e SPEECHES AND MEETINGS 36 e FINANCIALS 40 e Wildlife AWI seeks to reduce the detrimental impacts of human activities on wild animals. We work to strengthen national and international wildlife protection and advocate for humane solutions to confl icts with wildlife. 2 International trade Restoring habitat AWI’s D.J. Schubert and Sue Fisher participated For wildlife species depleted by habitat loss in the 69th meeting of the Standing Committee and historic hunting pressure, AWI seeks to of the Convention on International Trade in provide suitable habitat to facilitate their return. -

Re-Imagining the Animal in J.M. Coetzee's the Lives of Animals

Re-imagining the Animal in J.M. Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals A.M. Wattam 2019 Re-imagining the Animal in J.M. Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals By Amy McLeod Wattam Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium (English) in the Faculty of Arts at Nelson Mandela University Supervisor: Prof Marius Crous Co-Supervisor: Dr Jakub Siwak April 2019 Declaration by candidate Name: Amy Wattam Student number: 211257346 Qualification: Master of Arts (English) Title of project: Re-imagining the Animal in J.M. Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals Declaration: In accordance with Rule G5.6.3, I, Amy Wattam (211257346), hereby declare that the abovementioned dissertation is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. Signature: Amy McLeod Wattam Date: 15 April 2019 Contents i. Acknowledgements ii. Abstract Introduction 1 Chapter One: Studying The Lives of Animals – Situation, Reception and Theory 7 1.1. Introduction 7 1.2. Situating The Lives of Animals 8 1.3. Critical Reception 16 1.4. A Posthumanist Reading 18 1.5. Conclusion 28 Chapter Two: Coetzee and Unsettling Boundaries of (Re)presentation 30 2.1. Introduction 30 2.2. Coetzee’s Multimodal Metafiction 31 2.3. Coetzee’s Relation to The Lives of Animals 40 2.4. Coetzee’s Multi-layered Responses 51 2.5. Conclusion 62 Chapter Three: Disconnections in The Lives of Animals 64 3.1. Introduction 64 3.2. Human versus Animal 65 3.3. Reason versus Feeling 75 3.4. -

Dog Meat Trade in South Korea: a Report on the Current State of the Trade and Efforts to Eliminate It

DOG MEAT TRADE IN SOUTH KOREA: A REPORT ON THE CURRENT STATE OF THE TRADE AND EFFORTS TO ELIMINATE IT By Claire Czajkowski* Within South Korea, the dog meat trade occupies a liminal legal space— neither explicitly condoned, nor technically prohibited. As a result of ex- isting in this legal gray area, all facets of the dog meat trade within South Korea—from dog farms, to transport, to slaughter, to consumption—are poorly regulated and often obfuscated from review. In the South Korean con- text, the dog meat trade itself not only terminally impacts millions of canine lives each year, but resonates in a larger national context: raising environ- mental concerns, and standing as a proxy for cultural and political change. Part II of this Article describes the nature of the dog meat trade as it oper- ates within South Korea; Part III examines how South Korean law relates to the dog meat trade; Part IV explores potentially fruitful challenges to the dog meat trade under South Korean law; similarly, Part V discusses grow- ing social pressure being deployed against the dog meat trade. I. INTRODUCTION ......................................... 30 II. STATE OF THE ISSUE ................................... 32 A. Scope of the Dog Meat Trade in South Korea ............ 32 B. Dog Farms ............................................ 33 C. Slaughter Methods .................................... 35 D. Markets and Restaurants .............................. 37 III. SOUTH KOREAN CULTURE AND LAWS ................. 38 A. Society and Culture ................................... 38 B. Current Laws ......................................... 40 1. Overview of Korean Law ............................ 40 a. Judicial System ................................ 41 b. Sources of Law ................................. 42 2. Animal Protection Act .............................. 42 a. Recently Passed Amendments .................... 45 b. Recently Proposed Amendments ................. -

Quarterly Winter 2007 Volume 56 Number 1 About the Cover Young Jersey Cattle Graze on Lush Pastures at the Cates Family Farm in Wisconsin (Photo by Diane Halverson)

AWI Quarterly Winter 2007 Volume 56 Number 1 about the cover Young Jersey cattle graze on lush pastures at the Cates Family Farm in Wisconsin (photo by Diane Halverson). At this Animal Welfare Approved farm, Kim and Dick Cates buy male calves from local dairy farmers and raise them for beef. The Cates’ dedication to family farming and sustainable land and forest management is well- known. Considering the welfare of their calves, who would have otherwise been sent to auction houses or intensive veal operations, is a natural part of their overall commitment to caring for the earth and its inhabitants. The Animal Welfare Approved husbandry standards for all species, including animals on the farm cattle raised for beef, mandate the provision of an environment, housing and diet that is designed to allow animals to behave naturally. Each animal must be able to Introducing Animal Welfare Approved...4-7 perform behaviors that promote their physiological and psychological health and Celebrating 30 Years of Preserving Breeds...8 AWI well-being (see story pages 4-7). Smithfield in the News: Progress or Persiflage?...8 Quarterly www.WorldParrotTrust.org Winter 2007 Volume 56 Number 1 Starbucks: No More rBGH...8 Farm Owners and Worker Charged with Animal Cruelty...15 FOUNDER Texas Anti-Horse Slaughter Law Upheld...15 Christine Stevens DIRECTORS animals in the wild Cynthia Wilson, Chair Cramped quarters and extreme stress for birds Barbara K. Buchanan during transport encourage the outbreak of Biologist Robert Schmidt Joins AWI Scientific Committee...12 Marjorie Cooke infectious diseases such as avian influenza. EU Bans Import of Wild-Caught Birds; CITES Takes Issue...12 Penny Eastman page 12 Roger Fouts, Ph.D. -

Liberté, Égalité, Animalité: Human–Animal Comparisons In

Transnational Environmental Law, Page 1 of 29 © 2016 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S204710251500031X SYMPOSIUM ARTICLE Liberté, Égalité, Animalité: † Human–Animal Comparisons in Law Anne Peters* Abstract This article problematizes the discrepancy between the wealth of international law serving human needs and rights and the international regulatory deficit concerning animal welfare and animal rights. It suggests that, in the face of scientific evidence, the legal human–animal boundary (as manifest notably in the denial of rights to animals) needs to be properly justified. Unmasking the (to some extent) ‘imagined’ nature of the human–animal boundary, and shedding light on the persistence of human–animal comparisons for pernicious and beneficial purposes of the law, can offer inspirations for legal reform in the field of animal welfare and even animal rights. Keywords Animal rights, Human rights, Animal welfare, Speciesism, Discrimination, Cultural imperialism 1. introduction: civilized humans against all others Between 1879 and 1935, the Basel Zoo in Switzerland entertained the public with Völkerschauen,or‘people’s shows’, in which non-European human beings were displayed wearing traditional dress, in front of makeshift huts, performing handcrafts.1 These shows attracted more visitors at the time than the animals in the zoo. The organizers of these Völkerschauen were typically animal dealers and zoo directors, and the humans exhibited were often recruited from Sudan, a region where most of the African zoo and circus animals were also being trapped. The organizers made sure that the individuals on display did not speak any European language, so that verbal communication between them and the zoo visitors was impossible. -

Annual Report

animal welfare institute annual report 09 animal welfare institute 58th annual report july 1, 2008 - june 30, 2009 table of contents09 albert schweitzer medal 1 animals in agriculture 2-5 animals in the wild 6-9 animals in the oceans 10-13 animals in laboratories 14-16 government and legal affairs 17-19 awi quarterly 20-27 awi publications 28 speeches and meetings 29-33 financial statements 34-35 awi representatives 36 albert schweitzer medal In 1951, Dr. Albert Schweitzer granted permission to the Animal Welfare Institute , a non- to award a medal in his name to individuals who have shown outstanding The animal welfare institute achievement in the advancement of animal welfare. Dr. Schweitzer wrote, “We profit charitable organization founded in 1951, is dedicated must try to demonstrate the essential worth of life by doing all we can to alleviate suffering.” Past recipients of the Albert Schweitzer Medal include: to alleviating suffering inflicted on animals by humans. • Senator Hubert H. Humphrey, 1958, for authoring the first humane slaughter bill Our legislative division seeks passage of laws that reflect in the U.S. Congress; this purpose. • Rachel Carson, 1962, for her landmark book Silent Spring, which spurred revolutionary changes in the laws affecting our air, land, water and wildlife; • Dr. Jane Goodall, 1987, for her lifetime of leadership in the protection of The Animal Welfare Institute aims to: chimpanzees; and • Abolish factory farms, support high-welfare family farms, and achieve • Henry Spira, 1996, coordinator of Animal Rights International, for a lifetime of humane slaughter for all animals raised for meat; activism that has impacted the lives of millions of animals in laboratory research, cosmetic testing and factory farming.