The Life of the Dairy Cow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Animal Law Received Generous Support from the Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Michigan State University College of Law

JOURNAL OF ANIMAL LAW Michigan State University College of Law APRIL 2009 Volume V J O U R N A L O F A N I M A L L A W Vol. V 2009 EDITORIAL BOARD 2008-2009 Editor-in-Chief ANN A BA UMGR A S Managing Editor JENNIFER BUNKER Articles Editor RA CHEL KRISTOL Executive Editor BRITT A NY PEET Notes & Comments Editor JA NE LI Business Editor MEREDITH SH A R P Associate Editors Tabb Y MCLA IN AKISH A TOWNSEND KA TE KUNK A MA RI A GL A NCY ERIC A ARMSTRONG Faculty Advisor DA VID FA VRE J O U R N A L O F A N I M A L L A W Vol. V 2009 Pee R RE VI E W COMMITT ee 2008-2009 TA IMIE L. BRY A NT DA VID CA SSUTO DA VID FA VRE , CH A IR RE B ECC A J. HUSS PETER SA NKOFF STEVEN M. WISE The Journal of Animal Law received generous support from the Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Michigan State University College of Law. Without their generous support, the Journal would not have been able to publish and host its second speaker series. The Journal also is funded by subscription revenues. Subscription requests and article submissions may be sent to: Professor Favre, Journal of Animal Law, Michigan State University College of Law, 368 Law College Building, East Lansing MI 48824. The Journal of Animal Law is published annually by law students at ABA accredited law schools. Membership is open to any law student attending an ABA accredited law college. -

Zoo Animal Welfare: the Human Dimension

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 10-2018 Zoo Animal Welfare: The Human Dimension Justine Cole University of British Columbia David Fraser University of British Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/zooaapop Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, and the Population Biology Commons Recommended Citation Justine Cole & David Fraser (2018) Zoo Animal Welfare: The Human Dimension, Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 21:sup1, 49-58, DOI: 10.1080/10888705.2018.1513839 This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOURNAL OF APPLIED ANIMAL WELFARE SCIENCE 2018, VOL. 21, NO. S1, 49–58 https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2018.1513839 Zoo Animal Welfare: The Human Dimension Justine Cole and David Fraser Faculty of Land and Food Systems, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Standards and policies intended to safeguard nonhuman animal welfare, Animal welfare; zoo animals; whether in zoos, farms, or laboratories, have tended to emphasize features keeper; stockperson; of the physical environment. However, research has now made it clear that attitudes; personality; well- very different welfare outcomes are commonly seen in facilities using being similar environments or conforming to the same animal -

Animal Rights Without Controversy

05__LESLIE_SUNSTEIN.DOC 7/20/2007 9:36 AM ANIMAL RIGHTS WITHOUT CONTROVERSY JEFF LESLIE* CASS R. SUNSTEIN** I INTRODUCTION Many consumers would be willing to pay something to reduce the suffering of animals used as food. Unfortunately, they do not and cannot, because existing markets do not disclose the relevant treatment of animals, even though that treatment would trouble many consumers. Steps should be taken to promote disclosure so as to fortify market processes and to promote democratic discussion of the treatment of animals. In the context of animal welfare, a serious problem is that people’s practices ensure outcomes that defy their existing moral commitments. A disclosure regime could improve animal welfare without making it necessary to resolve the most deeply contested questions in this domain. II OF THEORIES AND PRACTICES To all appearances, disputes over animal rights produce an extraordinary amount of polarization and acrimony. Some people believe that those who defend animal rights are zealots, showing an inexplicable willingness to sacrifice important human interests for the sake of rats, pigs, and salmon. Judge Richard Posner, for example, refers to “the siren song of animal rights,”1 while Richard Epstein complains that recognition of an “animal right to bodily integrity . Copyright © 2007 by Jeff Leslie and Cass R. Sunstein This article is also available at http://law.duke.edu/journals/lcp. * Associate Clinical Professor of Law and Director, Chicago Project on Animal Treatment Principles, University of Chicago Law School. ** Karl N. Llewellyn Distinguished Service Professor, Law School and Department of Political Science, University of Chicago. Many thanks are due to the McCormick Companions’ Fund for its support of the Chicago Project on Animal Treatment Principles, out of which this paper arises. -

Scientific Briefing on Caged Farming Overview of Scientific Research on Caged Farming of Laying Hens, Sows, Rabbits, Ducks, Geese, Calves and Quail

February 2021 Scientific briefing on caged farming Overview of scientific research on caged farming of laying hens, sows, rabbits, ducks, geese, calves and quail Contents I. Overview .............................................................................................. 4 Space allowances ................................................................................. 4 Other species-specific needs .................................................................... 5 Fearfulness ......................................................................................... 5 Alternative systems ............................................................................... 5 In conclusion ....................................................................................... 7 II. The need to end the use of cages in EU laying hen production .............................. 8 Enriched cages cannot meet the needs of hens ................................................. 8 Space ............................................................................................... 8 Respite areas, escape distances and fearfulness ............................................. 9 Comfort behaviours such as wing flapping .................................................... 9 Perching ........................................................................................... 10 Resources for scratching and pecking ......................................................... 10 Litter for dust bathing .......................................................................... -

Death-Free Dairy? the Ethics of Clean Milk

J Agric Environ Ethics https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-018-9723-x ARTICLES Death-Free Dairy? The Ethics of Clean Milk Josh Milburn1 Accepted: 10 January 2018 Ó The Author(s) 2018. This article is an open access publication Abstract The possibility of ‘‘clean milk’’—dairy produced without the need for cows—has been championed by several charities, companies, and individuals. One can ask how those critical of the contemporary dairy industry, including especially vegans and others sympathetic to animal rights, should respond to this prospect. In this paper, I explore three kinds of challenges that such people may have to clean milk: first, that producing clean milk fails to respect animals; second, that humans should not consume dairy products; and third, that the creation of clean milk would affirm human superiority over cows. None of these challenges, I argue, gives us reason to reject clean milk. I thus conclude that the prospect is one that animal activists should both welcome and embrace. Keywords Milk Á Food technology Á Biotechnology Á Animal rights Á Animal ethics Á Veganism Introduction A number of businesses, charities, and individuals are working to develop ‘‘clean milk’’—dairy products created by biotechnological means, without the need for cows. In this paper, I complement scientific work on this possibility by offering the first normative examination of clean dairy. After explaining why this question warrants consideration, I consider three kinds of objections that vegans and animal activists may have to clean milk. First, I explore questions about the use of animals in the production of clean milk, arguing that its production does not involve the violation of & Josh Milburn [email protected] http://josh-milburn.com 1 Department of Politics, University of York, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, UK 123 J. -

Reasonable Humans and Animals: an Argument for Vegetarianism

BETWEEN THE SPECIES Issue VIII August 2008 www.cla.calpoly.edu/bts/ Reasonable Humans and Animals: An Argument for Vegetarianism Nathan Nobis Philosophy Department Morehouse College, Atlanta, GA USA www.NathanNobis.com [email protected] “It is easy for us to criticize the prejudices of our grandfathers, from which our fathers freed themselves. It is more difficult to distance ourselves from our own views, so that we can dispassionately search for prejudices among the beliefs and values we hold.” - Peter Singer “It's a matter of taking the side of the weak against the strong, something the best people have always done.” - Harriet Beecher Stowe In my experience of teaching philosophy, ethics and logic courses, I have found that no topic brings out the rational and emotional best and worst in people than ethical questions about the treatment of animals. This is not surprising since, unlike questions about social policy, generally about what other people should do, moral questions about animals are personal. As philosopher Peter Singer has observed, “For most human beings, especially in modern urban and suburban communities, the most direct form of contact with non-human animals is at mealtimes: we eat Between the Species, VIII, August 2008, cla.calpoly.edu/bts/ 1 them.”1 For most of us, then, our own daily behaviors and choices are challenged when we reflect on the reasons given to think that change is needed in our treatment of, and attitudes toward, animals. That the issue is personal presents unique challenges, and great opportunities, for intellectual and moral progress. Here I present some of the reasons given for and against taking animals seriously and reflect on the role of reason in our lives. -

Dairy Cow Unified Scorecard

DAIRY COW UNIFIED SCORECARD Breed characteristics should be considered in the application of this scorecard. Perfect MAJOR TRAIT DESCRIPTIONS Score There are four major breakdowns on which to base a cow’s evaluation. Each trait is broken down into body parts to be considered and ranked. 1) Frame - 15% The skeletal parts of the cow, with the exception of rear feet and legs. Listed in priority order, the descriptions of the traits to be considered are as follows: Rump (5 points): Should be long and wide throughout. Pin bones should be slightly lower than hip bones with adequate width between the pins. Thurls 15 should be wide apart. Vulva should be nearly vertical and the anus should not be recessed. Tail head should set slightly above and neatly between pin bones with freedom from coarseness. Front End (5 points): Adequate constitution with front legs straight, wide apart, and squarely placed. Shoulder blades and elbows set firmly against the chest wall. The crops should have adequate fullness blending into the shoulders. Back/Loin (2 points): Back should be straight and strong, with loin broad, strong, and nearly level. Stature (2 points): Height including length in the leg bones with a long bone pattern throughout the body structure. Height at withers and hips should be relatively proportionate. Age and breed stature recommendations are to be considered. Breed Characteristics (1 point): Exhibiting overall style and balance. Head should be feminine, clean-cut, slightly dished with broad muzzle, large open nostrils and strong jaw. 2) Dairy Strength - 25% A combination of dairyness and strength that supports sustained production and longevity. -

An HSUS Report: the Welfare of Animals in the Meat, Egg, and Dairy Industries

An HSUS Report: The Welfare of Animals in the Meat, Egg, and Dairy Industries Abstract Each year in the United States, approximately 11 billion animals are raised and killed for meat, eggs, and milk. These farm animals—sentient, complex, and capable of feeling pain and frustration, joy and excitement—are viewed by industrialized agriculture as commodities and suffer myriad assaults to their physical, mental, and emotional well-being, typically denied the ability to engage in their species-specific behavioral needs. Despite the routine abuses they endure, no federal law protects animals from cruelty on the farm, and the majority of states exempt customary agricultural practices—no matter how abusive—from the scope of their animal cruelty statutes. The treatment of farm animals and the conditions in which they are raised, transported, and slaughter within industrialized agriculture are incompatible with providing adequate levels of welfare. Birds Of the approximately 11 billion animals killed annually in the United States,1,2,3,4,5 86% are birds—98% of land animals in agriculture—and the overwhelming majority are “broiler” chickens raised for meat, approximately 1 million killed each hour.6 Additionally, approximately 340 million laying hens7 are raised in the egg industry (280 million birds who produce table eggs and 60 million kept for breeding), and more than 270 million turkeys8 are slaughtered for meat. On factory farms, birds raised for meat are confined by the tens of thousands9,10 in grower houses, which are commonly artificially lit, force-ventilated, and completely barren except for litter material on the floor and long rows of feeders and drinkers. -

Quarterly Fall 2010 Volume 59 Number 4

AW I Quarterly Fall 2010 Volume 59 Number 4 AWI ABOUT THE COVER Quarterly ANIMAL WELFARE INSTITUTE QUARTERLY Baby black rhinoceros, Maalim, is heading in for his evening bottle and then a good night’s sleep at the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust outside Nairobi. Apparently abandoned by his FOUNDER mother, days-old Maalim (named for the ranger who rescued him) was found in the Ngulia Christine Stevens Rhino Sanctuary and taken to the Trust. Now at 20 months, he has grown quite a bit but is DIRECTORS still just hip-high! Black rhinos, critically endangered with a total wild population believed to Cynthia Wilson, Chair be around 4,200 animals, continue to be poached (along with white rhinos) for their horns. Barbara K. Buchanan “Into Africa” on p. 14 chronicles the visit to the Trust and other Kenyan conservation program John Gleiber sites by AWI’s Cathy Liss. Charles M. Jabbour Mary Lee Jensvold, Ph.D. Photo by Cathy Liss Cathy Liss 4 Michele Walter OFFICERS Cathy Liss, President Cynthia Wilson, Vice President Brutal BLM Roundups Charles M. Jabbour, CPA, Treasurer John Gleiber, Secretary THE UNNECESSARY REMOVAL OF WILD HORSES has reached an alarming rate SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE under the current administration. Thousands of horses have been and continue to Gerard Bertrand, Ph.D. be removed from their native range, and placed in short- and long-term holding Roger Fouts, Ph.D. facilities in the Roger Payne, Ph.D. Midwest. Taxpayers 10 22 Samuel Peacock, M.D. Hope Ryden pay tens of millions Robert Schmidt of dollars a year to John Walsh, M.D. -

Guinea Pigs 79 Group Housing of Males 79 Proper Diet to Prevent Obesity 81 Straw Bedding 83

Caring DiscussionsHands by the Laboratory Animal Refinement & Enrichment Forum Volume II Edited by Viktor Reinhardt Animal Welfare Institute Animal Welfare Institute 900 Pennsylvania Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20003 www.awionline.org Caring Hands Discussions by the Laboratory Animal Refinement & Enrichment Forum, Volume 2 Edited by Viktor Reinhardt Copyright ©2010 Animal Welfare Institute Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-938414-88-9 LCCN 2010910475 Cover photo: Jakub Hlavaty Design: Ava Rinehart and Cameron Creinin Copy editing: Beth Herman, Cathy Liss, Annie Reinhardt and Dave Tilford All papers used in this publication are Acid Free and Elemental Chlorine Free. They also contain 50% recycled content including 30% post consumer waste. All raw materials originate in forests run according to correct principles in full respect for high environmental, social and economic standards at all stages of production. I am dedicating this book to the innocent animal behind bars who has to endure loneliness, boredom and unnecessary distress. Table of Contents Introduction and Acknowledgements i Chapter 1: Basic Issues 2 Annual Usage of Animals in Biomedical Research 4 Cage Space 10 Inanimate Enrichment 16 Enrichment versus Enhancement 17 Behavioral Problems 22 Mood Swings 24 Radio Music/Talk 29 Construction Noise and Vibration Chapter 2: Refinement and Enrichment for Rodents and Rabbits Environmental Enrichment 34 Institutional Standards 35 Foraging Enrichment 36 Investigators’ Permission 38 Rats 40 Amazing Social Creatures 40 Are -

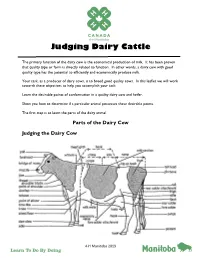

Judging Dairy Cattle

Judging Dairy Cattle The primary function of the dairy cow is the economical production of milk. It has been proven that quality type or form is directly related to function. In other words, a dairy cow with good quality type has the potential to efficiently and economically produce milk. Your task, as a producer of dairy cows, is to breed good quality cows. In this leaflet we will work towards these objectives to help you accomplish your task. Learn the desirable points of conformation in a quality dairy cow and heifer. Show you how to determine if a particular animal possesses these desirable points. The first step is to learn the parts of the dairy animal. Parts of the Dairy Cow Judging the Dairy Cow 4-H Manitoba 2019 Once you know the parts of the body, the next step to becoming a successful dairy judge is to learn what the ideal animal looks like. In this section, we will work through the parts of a dairy cow and learn the desirable and undesirable characteristics. Holstein Canada has developed a scorecard which places relative emphasis on the six areas of importance in the dairy cow. This scorecard is used by all dairy breeds in Canada. The Holstein Cow Scorecard uses these six areas: 1. Frame / Capacity 2. Rump 3. Feet and Legs 4. Mammary System 5. Dairy Character When you judge, do not assign numerical scores. Use the card for relative emphasis only. When cows are classified by the official breed classifiers, classifications and absolute scores are assigned. 2 HOLSTEIN COW SCORE CARD 18 1. -

The Legal Guardianship of Animals.Pdf

Edna Cardozo Dias Lawyer, PhD in Law, Legal Consultant and University Professor The Legal Guardianship of Animals Belo Horizonte - Minas Gerais 2020 © 2020 EDNA CARDOZO DIAS Editor Edna Cardozo Dias Final art Aderivaldo Sousa Santos Review Maria Celia Aun Cardozo, Edna The Legal Guardianship of Animals / — Edna Cardozo Dias: Belo Horizonte/Minas Gerais - 2020 - 3ª edition. 346 p. 1. I.Título. Printed in Brazil All rights reserved Requests for this work Internet site shopping: amazon.com.br and amazon.com. Email: [email protected] 2 EDNA CARDOZO DIAS I dedicate this book To the common mother of all beings - the Earth - which contains the essence of all that lives, which feeds us from all joys, in the hope that this work may inaugurate a new era, marked by a firm purpose to restore the animal’s dignity, and the human being commitment with an ethic of life. THE LEGAL GUARDIANSHIP OF A NIMALS 3 Appreciate Professor Arthur Diniz, advisor of my doctoral thesis, defended at the Federal University of Minas Gerais - UFMG, which was the first thesis on animal law in Brazil in February 2000, introducing this new branch of law in the academic and scientific world, starting the elaboration of a “Animal Rights Theory”. 4 EDNA CARDOZO DIAS Sumário Chapter 1 - PHILOSOPHY AND ANIMALS .................................................. 15 1.1 The Greeks 1.1.1 The Pre-Socratic 1.1.2 The Sophists 1.1.3 The Socratic Philosophy 1.1.4 Plato 1.1.5 Peripathetism 1.1.6 Epicureanism 1.1.7 The Stoic Philosophy 1.2 The Biblical View - The Saints and the Animals 1.2.1 St.