Ecological Law, Interspecies Justice, and the Global Food System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nonhuman Rights to Personhood

Pace Environmental Law Review Volume 30 Issue 3 Summer 2013 Article 10 July 2013 Nonhuman Rights to Personhood Steven M. Wise Nonhuman Rights Project Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pelr Part of the Animal Law Commons, and the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven M. Wise, Nonhuman Rights to Personhood, 30 Pace Envtl. L. Rev. 1278 (2013) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pelr/vol30/iss3/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Environmental Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYSON LECTURE Nonhuman Rights to Personhood STEVEN M. WISE I. INTRODUCTION Thank you all for joining us for the second Dyson Lecture of 2012. We were very lucky to have a first Dyson Lecture, and we will have an even more successful lecture this time. We have a very distinguished person I will talk about in just a second. I’m David Cassuto, a Pace Law School professor. I teach among other things, Animal Law, and that is why I am very familiar with Professor Wise’s work. I want to say a few words about the Dyson Lecture. The Dyson Distinguished Lecture was endowed in 1982 by a gift from the Dyson Foundation, which was made possible through the generosity of the late Charles Dyson, a 1930 graduate, trustee, and long-time benefactor of Pace University. The principle aim of the Dyson Lecture is to encourage and make possible scholarly legal contributions of high quality in furtherance of Pace Law School’s educational mission and that is very much what we are going to have today. -

Grain Legumes (Pulses) for Profitable and Sustainable Cropping Systems in WA

PULSES IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA Grain legumes (pulses) for profitable and sustainable cropping systems in WA Professor Kadambot Siddique The UWA Institute of Agriculture, The University of Western Australia UN FAO Special Ambassador for the International Year of Pulses 2016 Introduction biotic stresses, increasing their risk by cultivation, and the lower grain yield potential of legumes THE IMPORTANCE of grain legumes in compared with competing cereal crops. While improving the health of humans, the livestock genetic improvement is required to address they nurture and the soil in which they grow, these problems, agronomic improvements can and in mitigating greenhouse gases (Siddique et significantly contribute to closing the yield gap al. 2012) is increasingly recognised. Legumes are induced by various stresses (Siddique et al. 2012; important because they fix atmospheric nitrogen Anderson et al. 2016). Practically, however, genetic in the soil through a symbiotic relationship with and agronomic improvements should proceed in the bacterium of the genus Rhizobium, with some a complementary manner as a new variety often of this nitrogen available for the succeeding requires a change in agronomic practice to achieve crop. Grain legumes have the added benefit of potential yields. producing grains that are rich in protein (excellent human food) and can be commercially traded. The inclusion of grain legumes in a cropping system Grain legumes in increases soil organic matter, provides a disease Australian cropping systems break for succeeding cereal and canola crops, and The value of the contribution of grain legumes improves water use efficiency. (pulses) to sustainable cropping has been amply Nevertheless, grain legumes remain poor cousins demonstrated (Siddique et al. -

COURT of APPEALS of the STATE of NEW YORK ------X in the Matter of a Proceeding Under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus

COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------x In the Matter of a Proceeding under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on Index Nos. 162358/15 behalf of TOMMY, (New York County); Petitioner-Appellant, 150149/16 (New York -against- County) PATRICK C. LAVERY, individually and as an of Circle L Trailer Sales, Inc., DIANE LAVERY, and CIRCLE L TRAILER SALES, INC., Respondents-Respondents, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on behalf of KIKO, Petitioner-Appellant, -against- CARMEN PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., CHRISTIE E. PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., and THE PRIMATE SANCTUARY, INC., Respondents-Respondents. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------x MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR PERMISSION TO APPEAL TO THE COURT OF APPEALS Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Steven M. Wise, Esq. 5 Dunhill Road (of the Bar of the State of New Hyde Park, New York Massachusetts) 11040 By Permission of the Court (516) 747-4726 5195 NW 112th Terrace [email protected] Coral Springs, Florida 33076 (954) 648-9864 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Authorities ................................................................................... iv Argument .................................................................................................... 1 I. Preliminary Statement -

Vegetables, Fruits, Whole Grains, and Beans

Vegetables, Fruits, Whole Grains, and Beans Session 2 Assessment Background Information Tips Goals Vegetables, Fruit, Assessment of Whole Grains, Current Eating Habits and Beans On an average DAY, how many servings of these Could be Needs to foods do you eat or drink? Desirable improved be improved 1. Greens and non-starchy vegetables like collard, 4+ 2-3 0-1 mustard, or turnip greens, salads made with dark- green leafy lettuces, kale, broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, carrots, okra, zucchini, squash, turnips, onions, cabbage, spinach, mushrooms, bell peppers, or tomatoes (including tomato sauce) 2. Fresh, canned (in own juice or light syrup), or 3+ 1-2 0 frozen fruit or 100% fruit juice (½ cup of juice equals a serving) 3a. Bread, rolls, wraps, or tortillas made all or mostly Never Some Most of with white flour of the time the time 3b. Bread, rolls, wraps, or tortillas made all or mostly Most Some Never with whole wheat flour of the time of the time In an average WEEK, how many servings of these foods do you eat? 4. Starchy vegetables like acorn squash, butternut 4-7 2-3 0-1 squash, beets, green peas, sweet potatoes, or yams (do not include white potatoes) 5. White potatoes, including French fries and 1 or less 2-3 4+ potato chips 6. Beans or peas like pinto beans, kidney beans, 3+ 1-2 0 black beans, lentils, butter or lima beans, or black-eyed peas Continued on next page Vegetables, Fruit, Whole Grains, and Beans 19 Vegetables, Fruit, Whole Grains, Assessment of and Beans Current Eating Habits In an average WEEK, how often or how many servings of these foods do you eat? 7a. -

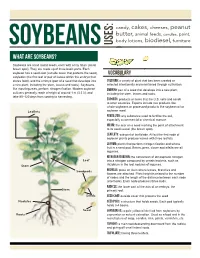

What Are Soybeans?

candy, cakes, cheeses, peanut butter, animal feeds, candles, paint, body lotions, biodiesel, furniture soybeans USES: What are soybeans? Soybeans are small round seeds, each with a tiny hilum (small brown spot). They are made up of three basic parts. Each soybean has a seed coat (outside cover that protects the seed), VOCABULARY cotyledon (the first leaf or pair of leaves within the embryo that stores food), and the embryo (part of a seed that develops into Cultivar: a variety of plant that has been created or a new plant, including the stem, leaves and roots). Soybeans, selected intentionally and maintained through cultivation. like most legumes, perform nitrogen fixation. Modern soybean Embryo: part of a seed that develops into a new plant, cultivars generally reach a height of around 1 m (3.3 ft), and including the stem, leaves and roots. take 80–120 days from sowing to harvesting. Exports: products or items that the U.S. sells and sends to other countries. Exports include raw products like whole soybeans or processed products like soybean oil or Leaflets soybean meal. Fertilizer: any substance used to fertilize the soil, especially a commercial or chemical manure. Hilum: the scar on a seed marking the point of attachment to its seed vessel (the brown spot). Leaflets: sub-part of leaf blade. All but the first node of soybean plants produce leaves with three leaflets. Legume: plants that perform nitrogen fixation and whose fruit is a seed pod. Beans, peas, clover and alfalfa are all legumes. Nitrogen Fixation: the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen Leaf into a nitrogen compound by certain bacteria, such as Stem rhizobium in the root nodules of legumes. -

Zoo Animal Welfare: the Human Dimension

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 10-2018 Zoo Animal Welfare: The Human Dimension Justine Cole University of British Columbia David Fraser University of British Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/zooaapop Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, and the Population Biology Commons Recommended Citation Justine Cole & David Fraser (2018) Zoo Animal Welfare: The Human Dimension, Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 21:sup1, 49-58, DOI: 10.1080/10888705.2018.1513839 This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOURNAL OF APPLIED ANIMAL WELFARE SCIENCE 2018, VOL. 21, NO. S1, 49–58 https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2018.1513839 Zoo Animal Welfare: The Human Dimension Justine Cole and David Fraser Faculty of Land and Food Systems, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Standards and policies intended to safeguard nonhuman animal welfare, Animal welfare; zoo animals; whether in zoos, farms, or laboratories, have tended to emphasize features keeper; stockperson; of the physical environment. However, research has now made it clear that attitudes; personality; well- very different welfare outcomes are commonly seen in facilities using being similar environments or conforming to the same animal -

Sterilization, Hunting and Culling : Combining Management Approaches for Mitigating Suburban Deer Impacts

Poster Presentation Sterilization, Hunting and Culling: Combining Management Approaches for Mitigating Suburban Deer Impacts J.R. Boulanger University of North Dakota P.D. Curtis and M.L. Ashdown Cornell University ABSTRACT: Based on decades of growing deer impacts on local biodiversity, agricultural damage, and deer-vehicle collisions, in 2007 we implemented an increasingly aggressive suburban deer research and management program on Cornell University lands in Tompkins County, New York. We initially divided Cornell lands into a suburban core campus area (1,100 acres [4.5 km2]) and adjacent outlying areas that contain lands where deer hunting was permitted (~4,000 acres [16.2 km2]). We attempted to reduce deer numbers by surgically sterilizing deer in the core campus zone and increasing harvest of female deer in the hunting zone through an Earn-a-Buck program. During the first 6 years of this study, project staff spayed 96 female deer (>90% of all deer on campus); 69 adult does were marked with radio transmitters to monitor movements and survival. From 2008 to 2013, hunters harvested >600 deer (69–165 each hunting season). By winter 2013, we stabilized the campus deer herd to approximately 100 animals (57 deer/mi2 [22 deer/km2]), a density much higher than project goals (14 deer/mi2). Although we reduced doe and fawn numbers by approximately 38% and 79%, respectfully, this decrease was offset by an increase in bucks that appeared on camera during our population study. In 2014, we supplemented efforts using deer damage permits (DDP) with archery sharpshooting over bait, and collapsible Clover traps with euthanasia by penetrating captive bolt. -

ASEBL Journal

January 2019 Volume 14, Issue 1 ASEBL Journal Association for the Study of EDITOR (Ethical Behavior)•(Evolutionary Biology) in Literature St. Francis College, Brooklyn Heights, N.Y. Gregory F. Tague, Ph.D. ▬ ~ GUEST CO-EDITOR ISSUE ON GREAT APE PERSONHOOD Christine Webb, Ph.D. ~ (To Navigate to Articles, Click on Author’s Last Name) EDITORIAL BOARD — Divya Bhatnagar, Ph.D. FROM THE EDITORS, pg. 2 Kristy Biolsi, Ph.D. ACADEMIC ESSAY Alison Dell, Ph.D. † Shawn Thompson, “Supporting Ape Rights: Tom Dolack, Ph.D Finding the Right Fit Between Science and the Law.” pg. 3 Wendy Galgan, Ph.D. COMMENTS Joe Keener, Ph.D. † Gary L. Shapiro, pg. 25 † Nicolas Delon, pg. 26 Eric Luttrell, Ph.D. † Elise Huchard, pg. 30 † Zipporah Weisberg, pg. 33 Riza Öztürk, Ph.D. † Carlo Alvaro, pg. 36 Eric Platt, Ph.D. † Peter Woodford, pg. 38 † Dustin Hellberg, pg. 41 Anja Müller-Wood, Ph.D. † Jennifer Vonk, pg. 43 † Edwin J.C. van Leeuwen and Lysanne Snijders, pg. 46 SCIENCE CONSULTANT † Leif Cocks, pg. 48 Kathleen A. Nolan, Ph.D. † RESPONSE to Comments by Shawn Thompson, pg. 48 EDITORIAL INTERN Angelica Schell † Contributor Biographies, pg. 54 Although this is an open-access journal where papers and articles are freely disseminated across the internet for personal or academic use, the rights of individual authors as well as those of the journal and its editors are none- theless asserted: no part of the journal can be used for commercial purposes whatsoever without the express written consent of the editor. Cite as: ASEBL Journal ASEBL Journal Copyright©2019 E-ISSN: 1944-401X [email protected] www.asebl.blogspot.com Member, Council of Editors of Learned Journals ASEBL Journal – Volume 14 Issue 1, January 2019 From the Editors Shawn Thompson is the first to admit that he is not a scientist, and his essay does not pretend to be a scientific paper. -

3-Grain Veggie Burger and Slider

Featuring Chef’s Line™ Veggie Burger on 9-Grain Sprouted Bun 3-Grain VeGGIE BURGER AND SLIDER Made with brown rice, quinoa and bulgur, our all-natural vegan alternative to a meaty burger is flavorful and hearty 3-Grain Veggie Burger Designed and created for chefs with high standards The savory blend of hearty grains and roasted vegetables – and neutral flavor profile – invites you to create a signature burger. Product Inspiration Ideal Use Features/Benefits To capture the growing meatless trend, we’ve A hearty vegan and kosher option with a • Made with Distinction: lightly seasoned created a winning vegan burger that is neutral flavor profile adapts to your custom and made with a blend of high-quality upscale, hearty and made without soy creations and complements your beef burger ingredients, including visible vegetables; protein. Your vegan – and even nonvegan – offerings: no soy protein customers will immediately notice the • Vegetarian/vegan menus • Performance: eats like a beef burger; difference: a larger, thicker patty with a • Appetizers neutral flavor profile lets you customize meaty bite and crispy texture when grilled or • Food trucks creatively baked. Rich in fiber and protein and made • Tacos • Cost Savings: no thawing required; cook with only high-quality ingredients, it’s a • Catering opportunities only what you need magnificent addition to your menu. • Bar and grill • Labor Savings: preformed patties are easy • Colleges and universities to prepare from frozen Ingredients Include A-Code Product Description Pack Size – Corn – Black beans 1792399 3-Grain Veggie Burger 36/4.25 oz. – Roasted peppers – Mushrooms – Onions – Quinoa 1792431 3-Grain Veggie Slider 54/1.8 oz. -

Vegetarianism and World Peace and Justice

Visit the Triangle-Wide calendar of peace events, www.trianglevegsociety.org/peacecalendar VVeeggeettaarriiaanniissmm,, WWoorrlldd PPeeaaccee,, aanndd JJuussttiiccee By moving toward vegetarianism, can we help avoid some of the reasons for fighting? We find ourselves in a world of conflict and war. Why do people fight? Some conflict is driven by a desire to impose a value system, some by intolerance, and some by pure greed and quest for power. The struggle to obtain resources to support life is another important source of conflict; all creatures have a drive to live and sustain themselves. In 1980, Richard J. Barnet, director of the Institute for Policy Studies, warned that by the end of the 20th century, anger and despair of hungry people could lead to terrorist acts and economic class war [Staten Island Advance, Susan Fogy, July 14, 1980, p.1]. Developed nations are the largest polluters in the world; according to Mother Jones (March/April 1997, http://www. motherjones.com/mother_jones/MA97/hawken2.html), for example, Americans, “have the largest material requirements in the world ... each directly or indirectly [using] an average of 125 pounds of material every day ... Americans waste more than 1 million pounds per person per year ... less than 5 percent of the total waste ... gets recycled”. In the US, we make up 6% of the world's population, but consume 30% of its resources [http://www.enough.org.uk/enough02.htm]. Relatively affluent countries are 15% of the world’s population, but consume 73% of the world’s output, while 78% of the world, in developing nations, consume 16% of the output [The New Field Guide to the U. -

Animal Rights Without Controversy

05__LESLIE_SUNSTEIN.DOC 7/20/2007 9:36 AM ANIMAL RIGHTS WITHOUT CONTROVERSY JEFF LESLIE* CASS R. SUNSTEIN** I INTRODUCTION Many consumers would be willing to pay something to reduce the suffering of animals used as food. Unfortunately, they do not and cannot, because existing markets do not disclose the relevant treatment of animals, even though that treatment would trouble many consumers. Steps should be taken to promote disclosure so as to fortify market processes and to promote democratic discussion of the treatment of animals. In the context of animal welfare, a serious problem is that people’s practices ensure outcomes that defy their existing moral commitments. A disclosure regime could improve animal welfare without making it necessary to resolve the most deeply contested questions in this domain. II OF THEORIES AND PRACTICES To all appearances, disputes over animal rights produce an extraordinary amount of polarization and acrimony. Some people believe that those who defend animal rights are zealots, showing an inexplicable willingness to sacrifice important human interests for the sake of rats, pigs, and salmon. Judge Richard Posner, for example, refers to “the siren song of animal rights,”1 while Richard Epstein complains that recognition of an “animal right to bodily integrity . Copyright © 2007 by Jeff Leslie and Cass R. Sunstein This article is also available at http://law.duke.edu/journals/lcp. * Associate Clinical Professor of Law and Director, Chicago Project on Animal Treatment Principles, University of Chicago Law School. ** Karl N. Llewellyn Distinguished Service Professor, Law School and Department of Political Science, University of Chicago. Many thanks are due to the McCormick Companions’ Fund for its support of the Chicago Project on Animal Treatment Principles, out of which this paper arises. -

Soy Products As Healthy and Functional Foods

Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 7 (1): 71-80, 2011 ISSN 1990-9233 © IDOSI Publications, 2011 Soy Products as Healthy and Functional Foods Hossein Jooyandeh Department of Food Science and Technology, Ramin Agricultural and Natural Resources University, Mollasani, Khuzestan, Iran Abstract: Over the recent decades, researchers have documented the health benefits of soy protein, especially for those who take soy protein daily. Soy products offer a considerable appeal for a growing segment of consumers with certain dietary and health concerns. It is quite evident that soy products do reduce the risks of developing various age-related chronic diseases and epidemiologic data strongly suggest that populations that regularly consume soy products have reduced incidence and prevalence of the aforementioned age-related conditions and diseases than populations that eat very little soy. The subject of what specific components is responsible for the plethora of reported health benefits of soybean remains a strong controversial issue, as the scientific community continues to understand what component(s) in soy is /are responsible for its health benefits. Soy constituents’ benefits mostly relate to the reduction of cholesterol levels and menopause symptoms and the reduction of the risk for several chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease and osteoporosis. A variety of soy products are available on the market with different flavors and textures and a low-fat, nutritionally balanced diet can be developed from them. This article summarized the beneficial health, nutritional and functional properties of the soy ingredients and intends to illustrate the most current knowledge with a consciousness to motivate further research to optimize their favorable effects.