Zoo Animal Welfare: the Human Dimension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animal Rights Without Controversy

05__LESLIE_SUNSTEIN.DOC 7/20/2007 9:36 AM ANIMAL RIGHTS WITHOUT CONTROVERSY JEFF LESLIE* CASS R. SUNSTEIN** I INTRODUCTION Many consumers would be willing to pay something to reduce the suffering of animals used as food. Unfortunately, they do not and cannot, because existing markets do not disclose the relevant treatment of animals, even though that treatment would trouble many consumers. Steps should be taken to promote disclosure so as to fortify market processes and to promote democratic discussion of the treatment of animals. In the context of animal welfare, a serious problem is that people’s practices ensure outcomes that defy their existing moral commitments. A disclosure regime could improve animal welfare without making it necessary to resolve the most deeply contested questions in this domain. II OF THEORIES AND PRACTICES To all appearances, disputes over animal rights produce an extraordinary amount of polarization and acrimony. Some people believe that those who defend animal rights are zealots, showing an inexplicable willingness to sacrifice important human interests for the sake of rats, pigs, and salmon. Judge Richard Posner, for example, refers to “the siren song of animal rights,”1 while Richard Epstein complains that recognition of an “animal right to bodily integrity . Copyright © 2007 by Jeff Leslie and Cass R. Sunstein This article is also available at http://law.duke.edu/journals/lcp. * Associate Clinical Professor of Law and Director, Chicago Project on Animal Treatment Principles, University of Chicago Law School. ** Karl N. Llewellyn Distinguished Service Professor, Law School and Department of Political Science, University of Chicago. Many thanks are due to the McCormick Companions’ Fund for its support of the Chicago Project on Animal Treatment Principles, out of which this paper arises. -

Death-Free Dairy? the Ethics of Clean Milk

J Agric Environ Ethics https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-018-9723-x ARTICLES Death-Free Dairy? The Ethics of Clean Milk Josh Milburn1 Accepted: 10 January 2018 Ó The Author(s) 2018. This article is an open access publication Abstract The possibility of ‘‘clean milk’’—dairy produced without the need for cows—has been championed by several charities, companies, and individuals. One can ask how those critical of the contemporary dairy industry, including especially vegans and others sympathetic to animal rights, should respond to this prospect. In this paper, I explore three kinds of challenges that such people may have to clean milk: first, that producing clean milk fails to respect animals; second, that humans should not consume dairy products; and third, that the creation of clean milk would affirm human superiority over cows. None of these challenges, I argue, gives us reason to reject clean milk. I thus conclude that the prospect is one that animal activists should both welcome and embrace. Keywords Milk Á Food technology Á Biotechnology Á Animal rights Á Animal ethics Á Veganism Introduction A number of businesses, charities, and individuals are working to develop ‘‘clean milk’’—dairy products created by biotechnological means, without the need for cows. In this paper, I complement scientific work on this possibility by offering the first normative examination of clean dairy. After explaining why this question warrants consideration, I consider three kinds of objections that vegans and animal activists may have to clean milk. First, I explore questions about the use of animals in the production of clean milk, arguing that its production does not involve the violation of & Josh Milburn [email protected] http://josh-milburn.com 1 Department of Politics, University of York, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, UK 123 J. -

Reasonable Humans and Animals: an Argument for Vegetarianism

BETWEEN THE SPECIES Issue VIII August 2008 www.cla.calpoly.edu/bts/ Reasonable Humans and Animals: An Argument for Vegetarianism Nathan Nobis Philosophy Department Morehouse College, Atlanta, GA USA www.NathanNobis.com [email protected] “It is easy for us to criticize the prejudices of our grandfathers, from which our fathers freed themselves. It is more difficult to distance ourselves from our own views, so that we can dispassionately search for prejudices among the beliefs and values we hold.” - Peter Singer “It's a matter of taking the side of the weak against the strong, something the best people have always done.” - Harriet Beecher Stowe In my experience of teaching philosophy, ethics and logic courses, I have found that no topic brings out the rational and emotional best and worst in people than ethical questions about the treatment of animals. This is not surprising since, unlike questions about social policy, generally about what other people should do, moral questions about animals are personal. As philosopher Peter Singer has observed, “For most human beings, especially in modern urban and suburban communities, the most direct form of contact with non-human animals is at mealtimes: we eat Between the Species, VIII, August 2008, cla.calpoly.edu/bts/ 1 them.”1 For most of us, then, our own daily behaviors and choices are challenged when we reflect on the reasons given to think that change is needed in our treatment of, and attitudes toward, animals. That the issue is personal presents unique challenges, and great opportunities, for intellectual and moral progress. Here I present some of the reasons given for and against taking animals seriously and reflect on the role of reason in our lives. -

Dairy Cow Unified Scorecard

DAIRY COW UNIFIED SCORECARD Breed characteristics should be considered in the application of this scorecard. Perfect MAJOR TRAIT DESCRIPTIONS Score There are four major breakdowns on which to base a cow’s evaluation. Each trait is broken down into body parts to be considered and ranked. 1) Frame - 15% The skeletal parts of the cow, with the exception of rear feet and legs. Listed in priority order, the descriptions of the traits to be considered are as follows: Rump (5 points): Should be long and wide throughout. Pin bones should be slightly lower than hip bones with adequate width between the pins. Thurls 15 should be wide apart. Vulva should be nearly vertical and the anus should not be recessed. Tail head should set slightly above and neatly between pin bones with freedom from coarseness. Front End (5 points): Adequate constitution with front legs straight, wide apart, and squarely placed. Shoulder blades and elbows set firmly against the chest wall. The crops should have adequate fullness blending into the shoulders. Back/Loin (2 points): Back should be straight and strong, with loin broad, strong, and nearly level. Stature (2 points): Height including length in the leg bones with a long bone pattern throughout the body structure. Height at withers and hips should be relatively proportionate. Age and breed stature recommendations are to be considered. Breed Characteristics (1 point): Exhibiting overall style and balance. Head should be feminine, clean-cut, slightly dished with broad muzzle, large open nostrils and strong jaw. 2) Dairy Strength - 25% A combination of dairyness and strength that supports sustained production and longevity. -

An HSUS Report: the Welfare of Animals in the Meat, Egg, and Dairy Industries

An HSUS Report: The Welfare of Animals in the Meat, Egg, and Dairy Industries Abstract Each year in the United States, approximately 11 billion animals are raised and killed for meat, eggs, and milk. These farm animals—sentient, complex, and capable of feeling pain and frustration, joy and excitement—are viewed by industrialized agriculture as commodities and suffer myriad assaults to their physical, mental, and emotional well-being, typically denied the ability to engage in their species-specific behavioral needs. Despite the routine abuses they endure, no federal law protects animals from cruelty on the farm, and the majority of states exempt customary agricultural practices—no matter how abusive—from the scope of their animal cruelty statutes. The treatment of farm animals and the conditions in which they are raised, transported, and slaughter within industrialized agriculture are incompatible with providing adequate levels of welfare. Birds Of the approximately 11 billion animals killed annually in the United States,1,2,3,4,5 86% are birds—98% of land animals in agriculture—and the overwhelming majority are “broiler” chickens raised for meat, approximately 1 million killed each hour.6 Additionally, approximately 340 million laying hens7 are raised in the egg industry (280 million birds who produce table eggs and 60 million kept for breeding), and more than 270 million turkeys8 are slaughtered for meat. On factory farms, birds raised for meat are confined by the tens of thousands9,10 in grower houses, which are commonly artificially lit, force-ventilated, and completely barren except for litter material on the floor and long rows of feeders and drinkers. -

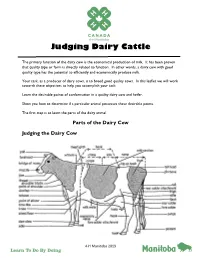

Judging Dairy Cattle

Judging Dairy Cattle The primary function of the dairy cow is the economical production of milk. It has been proven that quality type or form is directly related to function. In other words, a dairy cow with good quality type has the potential to efficiently and economically produce milk. Your task, as a producer of dairy cows, is to breed good quality cows. In this leaflet we will work towards these objectives to help you accomplish your task. Learn the desirable points of conformation in a quality dairy cow and heifer. Show you how to determine if a particular animal possesses these desirable points. The first step is to learn the parts of the dairy animal. Parts of the Dairy Cow Judging the Dairy Cow 4-H Manitoba 2019 Once you know the parts of the body, the next step to becoming a successful dairy judge is to learn what the ideal animal looks like. In this section, we will work through the parts of a dairy cow and learn the desirable and undesirable characteristics. Holstein Canada has developed a scorecard which places relative emphasis on the six areas of importance in the dairy cow. This scorecard is used by all dairy breeds in Canada. The Holstein Cow Scorecard uses these six areas: 1. Frame / Capacity 2. Rump 3. Feet and Legs 4. Mammary System 5. Dairy Character When you judge, do not assign numerical scores. Use the card for relative emphasis only. When cows are classified by the official breed classifiers, classifications and absolute scores are assigned. 2 HOLSTEIN COW SCORE CARD 18 1. -

WINNIPEG Vegetarian

www.ivu.org/wva WINNIPEG Vegetarian The Newsletter of the Winnipeg Vegetarian Association Issue 51 Fall 2005 What Would Jesus, Dairy Moses, Buddha and or Mohammed Eat? In a new pamphlet, the Society of Ethical and Religious Vegetarians surveys the veg'-friendliness of the world's major reli- Beef? gions. Here are some abridged high- lights. Read it all at serv-online.org. Which is Jainism Vegetarianism is expected practice among Jains, who Worse? hold that it is wrong to kill or harm any living being. By Dave Steele Islam It seems obvious enough. If you’re concerned about cows, It appears impossible for a faithful Muslim to con- dairy’s the way to go. Nobody gets killed, right? The cows sume meat produced by the cruel methods of facto- spend pleasant lives grazing in the fields, coming in for milking every now and then. Right? Contrast that with the ry farming. The Quran states, “There is not an ani- horrors of the slaughterhouse. mal on earth, nor a flying creature flying on two Unfortunately, things aren’t so simple. The small family wings, but they are peoples like unto you.” farms on which dairy cattle Mohammed taught, “A good deed done to a beast Most dairy cattle could roam between milk- is as good as doing good to a human being; while live out their lives ings are mostly gone now. an act of cruelty to a beast is as bad as an act of Instead, most dairy cattle cruelty to a human being.” Muslim theologian Al- in huge sheds live out their lives in huge Hafiz B. -

Sustainability: Veganism

Sustainability: Veganism Thomas Burgess, February 2020 In this report, IBISWorld analyst Thomas Burgess examines the rise of veganism, and the impact this movement has had on agriculture, food production and the consciousness of the population. Veganism was described by Claire Suddath as an the United Kingdom is rising and companies are adapting ‘extreme’ version of vegetarianism in a Time article in their practices to become more ethical. Fast-food 2008. However, veganism has since stepped out of the restaurants offering vegan options in an attempt to shadow of vegetarianism and is increasingly becoming expand their customer base has become the norm, and both a widespread, accepted diet and a political mainstay energy companies are aiming to show that they are in Western society, with campaigns such as Veganuary focused on the environment by committing to net-zero continuing to grow in popularity. In January 2020, a emissions by 2050. Health consciousness is closely tribunal ruled that ‘ethical veganism’ was a philosophical related, with the BBC reporting in January 2020 that belief under the Equality Act 2010, with these beliefs 49% of participants in a Mintel survey claimed they were deserving protection against discrimination as religious cutting down on meat consumption for health reasons. ones would. The level of environmental consciousness in Shoppers aim to live healthier lives whilst also saving Online searches in the UK* Comparing vegetarianism and veganism 80 70 60 50 Vegetarian 40 Vegan Popularity (%) 30 20 10 0 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Year *Yearly average SOURCE: GOOGLE TRENDS www.ibisworld.co.uk | 020 7222 9898 | [email protected] WWW.IBISWORLD.CO.UK 2 Sustainability: Veganism their wallets. -

Ecological Law, Interspecies Justice, and the Global Food System

DOES THE RULE OF ECOLOGICAL LAW DEMAND VEGANISM?: ECOLOGICAL LAW, INTERSPECIES JUSTICE, AND THE GLOBAL FOOD SYSTEM Heather McLeod-Kilmurray*† INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................455 I. DEFINING “ECOLOGICAL LAW” AND THE “GLOBAL (ANIMAL)FOOD SYSTEM”....................................................................................................458 II. DOES ECOLOGICAL LAW REQUIRE INTERSPECIES JUSTICE?.................464 III. DOES INTERSPECIES JUSTICE DEMAND (HUMAN)VEGANISM?...........465 IV.WOULD ENDING OR REDUCING INDUSTRIAL ANIMAL AGRICULTURE ENHANCEORCHALLENGE INTER- AND INTRAGENERATIONAL HUMAN JUSTICE?THE 10 FEATURESOFECOLOGICAL LAW AND THE INDUSTRIAL ANIMAL FOOD SYSTEM..............................................................................468 CONCLUSION:SOME SOLUTIONS THAT ECOLOGICAL LAW MIGHT POINT TOWARD.....................................................................................................479 INTRODUCTION Theconceptofecological lawchallengesmany fundamental assumptions andnorms of ourconventionalunderstandingsoflaw and requiresprofound changes to our usualapproachestosustainability.1 A somewhat less explored issueiswhether ecological lawrequiresorleadsus toward interspecies justice. To tacklethisquestion,Ihave chosen thecase study of our global industrialized food system,focusinginparticular on animal foods.Not onlydoeseatinganimalproducts directly raisethe issue of interspeciesjustice, butitacutely demonstratesthe challenges of achieving humanjustice(bothinter-and -

2017 Quiz Bowl Materials.Pages

2017 Virginia 4-H Dairy Quiz Bowl Materials ! Prepared by: David R. Winston Extension Dairy Scientist, Youth Department of Dairy Science (0315) Litton Reaves Hall, Room 2450, Virginia Tech 175 West Campus Drive Blacksburg, VA 24061 (540) 231-5693 [email protected] ! Table of Contents Chapter 1.................................................Dates in Dairy History ..............................................................3 Chapter 2 .............................................People and Organizations ...........................................................6 Chapter 3........................................................Dairy Breeds ...................................................................10 Chapter 4 .................................Dairy Cattle Judging, Fitting and Showing.............................................12 Chapter 5 ...........................................Calf and Heifer Management.......................................................16 Chapter 6 ...........................................Nutrition, Feeds and Feeding ......................................................19 Chapter 7 ......................................Lactation and Milking Management..................................................28 Chapter 8.......................................Dairy Products and Milk Marketing ..................................................35 Chapter 9.......................................................Miscellaneous ..................................................................42 Chapter 10 .....................................................Reproduction...................................................................46 -

Dairy Cattle Manual

B-6253 07/12 Lone Star Healthy Streams Dairy Cattle Manual Endorsed By: LONE STA R HEALTHY STREAMS Keeping Texas Waters Safe and Clean... Cover picture courtesy of USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Lone Star Healthy Streams Dairy Cattle Manual Authors Jennifer Peterson Extension Program Specialist Department of Soil & Crop Sciences Texas AgriLife Extension Service Ellen Jordan Professor and Extension Dairy Specialist Texas AgriLife Research and Extension Center Kevin Wagner Associate Director Texas Water Resources Institute Larry Redmon Professor and State Forage Specialist Department of Soil & Crop Sciences Texas AgriLife Extension Service © 2011 Photos.com, a division of Getty Images. All rights reserved. Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS....................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES........................................................................................................................ vii LIST OF TABLES.......................................................................................................................... ix PREFACE....................................................................................................................................... x CHAPTER 1: WATER QUALITY IN TEXAS Water Quality in Texas..................................................................................................................... 2 Value of Clean Water to Texas Agriculture...................................................................................... -

Dairy Cattle Reference

Learning About Dairy Revised September 2015 Authors Updated from the publication Learning About Dairy NCR593. Jim Paulson University of Minnesota Extension Jim Salfer University of Minnesota Extension Sherry Newell Midwest Dairy Association Elaine Santi Minnesota Department of Agriculture Tony Seykora College of Food, Agriculture and Natural Resource Sciences (CFANS), University of Minnesota Noah Litherland CFANS, University of Minnesota Marcia Endres CFANS, University of Minnesota Kevin Janni CFANS, University of Minnesota Jeff Reneau CFANS, University of Minnesota Neil Broadwater University of Minnesota Extension Chuck Schwartau University of Minnesota Extension Gretchen Rozeboom CFANS, University of Minnesota Extension Carolyn Suerth Hudson Midwest Dairy Council Lucas Salfer, Project Coordinator Meeker County 4-H Shari Schmidt, Support Staff University of Minnesota Extension 2010, revised 2015 Table of Contents Page Breed History 4 o Ayrshire 5 o Brown Swiss 6 o Guernsey 7 o Holstein 8 o Jersey 9 o Milking Shorthorn 10 o Montbeliarde 11 o Normande 12 o Red and Whites 13 o Swedish Reds 14 o Scandinavian Red Breeds 15 Dairy Cattle Genetics 16 Reproduction 21 Nutrition and Feeding 28 Herd Management and Health 35 Housing for Calves and Cows 42 Milking Management 46 The Milk Plant 53 Milk and Dairy Products 57 Dollars and Dairying 61 Cattle and Humans 70 Manure Management, Water Quality and Air Emissions 73 Proper Care of Dairy Cattle 77 Dairy Industry and Cooperative Structure 81 Careers in the Dairy Industry 84 Dairy Farm Systems Management 88 Workforce Management on the Dairy Farm 91 Parts of a Cow 94 Breed History Dairy Cattle Terms The Purebred Dairy Cattle Association (PDCA) is sponsored by the registered dairy breed associations in the United States.