Liberté, Égalité, Animalité: Human–Animal Comparisons In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Progressivism Cass R

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2005 A New Progressivism Cass R. Sunstein Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Cass R. Sunstein, "A New Progressivism" (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper No. 245, 2005). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO JOHN M. OLIN LAW & ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 245 (2D SERIES) A New Progressivism Cass R. Sunstein THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO May 2005 This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Chicago Working Paper Series Index: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html and at the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=726443 A New Progressivism Cass R. Sunstein* Abstract Based on an address for a conference on Law and Transformation in South Africa, this paper explores problems with two twentieth-century approaches to government: the way of markets and the way of planning. It urge that the New Progressivism simultaneously offers (1) a distinctive conception of government’s appropriate means, an outgrowth of the late-twentieth-century critique of economic planning, and (2) a distinctive understanding of government’s appropriate ends, an outgrowth of evident failures with market arrangements and largely a product of the mid-twentieth-century critique of laissez faire. -

Journal of Animal Law Received Generous Support from the Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Michigan State University College of Law

JOURNAL OF ANIMAL LAW Michigan State University College of Law APRIL 2009 Volume V J O U R N A L O F A N I M A L L A W Vol. V 2009 EDITORIAL BOARD 2008-2009 Editor-in-Chief ANN A BA UMGR A S Managing Editor JENNIFER BUNKER Articles Editor RA CHEL KRISTOL Executive Editor BRITT A NY PEET Notes & Comments Editor JA NE LI Business Editor MEREDITH SH A R P Associate Editors Tabb Y MCLA IN AKISH A TOWNSEND KA TE KUNK A MA RI A GL A NCY ERIC A ARMSTRONG Faculty Advisor DA VID FA VRE J O U R N A L O F A N I M A L L A W Vol. V 2009 Pee R RE VI E W COMMITT ee 2008-2009 TA IMIE L. BRY A NT DA VID CA SSUTO DA VID FA VRE , CH A IR RE B ECC A J. HUSS PETER SA NKOFF STEVEN M. WISE The Journal of Animal Law received generous support from the Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Michigan State University College of Law. Without their generous support, the Journal would not have been able to publish and host its second speaker series. The Journal also is funded by subscription revenues. Subscription requests and article submissions may be sent to: Professor Favre, Journal of Animal Law, Michigan State University College of Law, 368 Law College Building, East Lansing MI 48824. The Journal of Animal Law is published annually by law students at ABA accredited law schools. Membership is open to any law student attending an ABA accredited law college. -

Animals and Ethics Fall, 2017, P

Philosophy 174a Ethics and Animals Fall 2017 Instructor: Teaching Fellow: Chris Korsgaard Ahson Azmat 205 Emerson Hall [email protected] [email protected] Office Hours: Mondays 1:30-3:30 Description: Do human beings have moral obligations to the other animals? If so, what are they, and why? Should or could non-human animals have legal rights? Should we treat wild and domestic animals differently? Do human beings have the right to eat the other animals, raise them for that purpose on factory farms, use them in experiments, display them in zoos and circuses, make them race or fight for our entertainment, make them work for us, and keep them as pets? We will examine the work of utilitarian, Kantian, and Aristotelian philosophers, and others who have tried to answer these questions. This course, when taken for a letter grade, meets the General Education requirement for Ethical Reasoning. Sources and How to Get Them: Many of the sources from we will be reading from onto the course web site, but you will need to have copies of Singer’s Animal Liberation, Regan’s The Case for Animal Rights, Mill’s Utilitarianism and Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals. I have ordered all the main books from which we will be reading (except my own book, which is not yet published) at the Coop. The main books we will be using are: Animal Liberation, by Peter Singer. Updated edition, 2009, by Harper Collins Publishers. The Case for Animal Rights, by Tom Regan. University of California Press, 2004. Fellow Creatures: Our Obligations to the Other Animals, by Christine M. -

Rattling the Cage Defended Steven M

Boston College Law Review Volume 43 Article 2 Issue 3 Number 3 5-1-2002 Rattling the Cage Defended Steven M. Wise Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Animal Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven M. Wise, Rattling the Cage Defended, 43 B.C.L. Rev. 623 (2002), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol43/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RATTLING THE CAGE DEFENDED STEVEN M. WISE* Abstract: In Rattling the Cage: Toward Levi Rights for Animals, the author advocated basic legal rights—specifically common law rights—for chimpanzees, bonobos, and other nonhuman animals. In this Article, the author responds to many of the major criticisms of Rattling the Cage. The author confronts critics of his historical arguments for legal rights for nonhuman animals, tracing those arguments through ancient philosophy and nineteenth century English statutes. The author also expands upon his legal arguments for animal rights, reexamining various theories of rights and justifications for treating animals as property, Finally, borrowing from his upcoming book Drawing the Line: Science and The Case for Animal Rights, the author defends his advocacy of legal rights for nonhuman animals based on the relative autonomy nonhuman animals possess. INTRODUCTION "The 'animal rights' movement is gathering steam and Steven Wise is one of the pistons."l Thus Judge Richard Posner began a Yale Law Journal review of my book, Rattling the Cage: Toward Legal Rights for Animals, published in 2000. -

Scientific Briefing on Caged Farming Overview of Scientific Research on Caged Farming of Laying Hens, Sows, Rabbits, Ducks, Geese, Calves and Quail

February 2021 Scientific briefing on caged farming Overview of scientific research on caged farming of laying hens, sows, rabbits, ducks, geese, calves and quail Contents I. Overview .............................................................................................. 4 Space allowances ................................................................................. 4 Other species-specific needs .................................................................... 5 Fearfulness ......................................................................................... 5 Alternative systems ............................................................................... 5 In conclusion ....................................................................................... 7 II. The need to end the use of cages in EU laying hen production .............................. 8 Enriched cages cannot meet the needs of hens ................................................. 8 Space ............................................................................................... 8 Respite areas, escape distances and fearfulness ............................................. 9 Comfort behaviours such as wing flapping .................................................... 9 Perching ........................................................................................... 10 Resources for scratching and pecking ......................................................... 10 Litter for dust bathing .......................................................................... -

An Inquiry Into Animal Rights Vegan Activists' Perception and Practice of Persuasion

An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion by Angela Gunther B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication ! Angela Gunther 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Angela Gunther Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion Examining Committee: Chair: Kathi Cross Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Robert Anderson Supervisor Professor Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: June 28, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis interrogates the persuasive practices of Animal Rights Vegan Activists (ARVAs) in order to determine why and how ARVAs fail to convince people to become and stay veg*n, and what they might do to succeed. While ARVAs and ARVAism are the focus of this inquiry, the approaches, concepts and theories used are broadly applicable and therefore this investigation is potentially useful for any activist or group of activists wishing to interrogate and improve their persuasive practices. Keywords: Persuasion; Communication for Social Change; Animal Rights; Veg*nism; Activism iv Table of Contents Approval ............................................................................................................................. ii! Partial Copyright Licence ................................................................................................. -

Lesson Eight

Class of Nonviolence – Lesson Eight Animals, My Brethren by Edgar Kupfer-Koberwitz The following pages were written in the wounded or killed for my pleasure and Concentration Camp Dachau, in the midst of all convenience? kinds of cruelties. They were furtively scrawled in • Is it not only too natural that I do not a hospital barrack where I stayed during my inflict on other creatures the same thing illness, in a time when Death grasped day by day which, I hope and fear, will never be after us, when we lost twelve thousand within inflicted on me? Would it not be most four and a half months. unfair to do such things for no other purpose than for enjoying a trifling Dear Friend: physical pleasure at the expense of others' sufferings, others' deaths? You asked me why I do not eat meat and you are wondering at the reasons of my behavior. These creatures are smaller and more helpless Perhaps you think I took a vow -- some kind of than I am, but can you imagine a reasonable man penitence -- denying me all the glorious of noble feelings who would like to base on such pleasures of eating meat. You remember juicy a difference a claim or right to abuse the steaks, succulent fishes, wonderfully tasted weakness and the smallness of others? Don't you sauces, deliciously smoked ham and thousand think that it is just the bigger, the stronger, the wonders prepared out of meat, charming superior's duty to protect the weaker creatures thousands of human palates; certainly you will instead of persecuting them, instead of killing remember the delicacy of roasted chicken. -

Animal Rights

Book Review Animal Rights Richard A. Posner' Rattling the Cage: Toward Legal Rightsfor Animals. By Steven M. Wise. Cambridge,Mass.: PerseusBooks, 2000. Pp. 362. $25.00. The "animal rights" movement is gathering steam, and Steven Wise is one of the pistons. A lawyer whose practice is the protection of animals, he has now written a book in which he urges courts in the exercise of their common-law powers of legal rulemaking to confer legally enforceable rights on animals, beginning with chimpanzees and bonobos (the two most intelligent primate species).' Although Wise is well-informed about his subject-the biological as well as legal aspects-this is not an intellectually exciting book. I do not say this in criticism. Remember who Wise is: a practicing lawyer who wants to persuade the legal profession that courts should do much more to protect animals. Judicial innovation proceeds incrementally; as Holmes put it, the courts, in their legislative capacity, "are confined from molar to molecular motions."2 Wise's practitioner's perspective is, as we shall see, both the strength and the weakness of the book. f Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit; Senior Lecturer, University of Chicago Law School. I thank Michael Boudin, Richard Epstein, Lawrence Lessig, Martha Nussbaum, Charlene Posner, and Cass Sunstein for their very helpful comments on a previous draft of this Review. * Adjunct Professor, John Marshall Law School; Adjunct Professor, Vermont Law School; President, Center for the Expansion of Fundamental Rights; Partner, Wise & Slater-Wise, Boston. 1. These are closely related species, and Wise discusses them more or less interchangeably. -

The Use of Philosophers by the Supreme Court Neomi Raot

A Backdoor to Policy Making: The Use of Philosophers by the Supreme Court Neomi Raot The Supreme Court's decisions in Vacco v Quill' and Wash- ington v Glucksberg2 held that a state can ban assisted suicide without violating the Due Process or Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. In these high profile cases, six phi- losophers filed an amicus brief ("Philosophers'Brief') that argued for the recognition of a constitutional right to die.3 Although the brief was written by six of the most prominent American philoso- phers-Ronald Dworkin, Thomas Nagel, Robert Nozick, John Rawls, Thomas Scanlon, and Judith Jarvis Thomson-the Court made no mention of the brief in unanimously reaching the oppo- site conclusion.4 In light of the Court's recent failure to engage philosophical arguments, this Comment examines the conditions under which philosophy does and should affect judicial decision making. These questions are relevant in considering the proper role of the Court in controversial political questions and are central to a recent de- bate focusing on whether the law can still be considered an autonomous discipline that relies only on traditional legal sources. Scholars concerned with law and economics and critical legal studies have argued that the law is no longer autonomous, but rather that it does and should draw on many external sources in order to resolve legal disputes. Critics of this view have main- tained that legal reasoning is distinct from other disciplines, and that the law has and should maintain its own methods, conven- tions, and conclusions. This Comment follows the latter group of scholars, and ar- gues that the Court should, as it did in the right-to-die cases, stay clear of philosophy and base its decisions on history, precedent, and a recognition of the limits of judicial authority. -

Herald of the Golden Age V4 N8 Aug 15 1899

4 **" Circulation in Twenty-two Countries and Colonies. Postage—One Halfpenny. Golde •»r TN Vol. 4, No. 8. August 15, 1899. 0NE Pennv . o E n t e r e d a t S t a t i o n e r s ' H a u l . /-v, , Edited by Sidney H. Beard Contents U- The Peace of God ... Arthur Hurvte The Realm of Thought . Harold II'. U'histon A Visit to the Shambles . Editorial Notes ... Better-World Philosophy . J . Howard Moore 93 G lim pses ot Truth ... Household Wisdom ... Cbe Order of the Golden flge. G e n e r a l C o u n c i l : Sidney H, Eeard (Provost). Henry Brice % Church Road, St. Thomas, Exeter. H aro ld W . W h isto n . Overdale, Langley, Macclesfield. The above constitute the Executive Council. F r a n c e s L . B o u lt, 12, Hilldrop Crescent, London, N. R ev . A rth u r H a r v ie , 108, Avenue Road, Gateshead. A lb e rt B ro a d b e n t, Slade Lane, Longsighi, Manchester. R e v . A . M. M itc h e ll, M .A ., The Vicarage, Burton Wood, Lancashire Jo h n S. H e rro n , 29, High Street, Belfast. R e v . A d a m R u sh to n , Swiss Cottage, Upton, Macclesfield. L y d ia A . Ir o n s , Athol, Kootenai Co., Idaho, U.S.A. R e v . W a lte r W a ls h , 4, Nelson Terrace, Dundee. -

Quarterly Fall 2010 Volume 59 Number 4

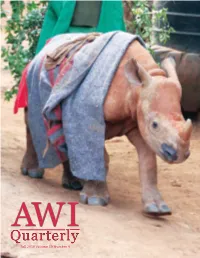

AW I Quarterly Fall 2010 Volume 59 Number 4 AWI ABOUT THE COVER Quarterly ANIMAL WELFARE INSTITUTE QUARTERLY Baby black rhinoceros, Maalim, is heading in for his evening bottle and then a good night’s sleep at the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust outside Nairobi. Apparently abandoned by his FOUNDER mother, days-old Maalim (named for the ranger who rescued him) was found in the Ngulia Christine Stevens Rhino Sanctuary and taken to the Trust. Now at 20 months, he has grown quite a bit but is DIRECTORS still just hip-high! Black rhinos, critically endangered with a total wild population believed to Cynthia Wilson, Chair be around 4,200 animals, continue to be poached (along with white rhinos) for their horns. Barbara K. Buchanan “Into Africa” on p. 14 chronicles the visit to the Trust and other Kenyan conservation program John Gleiber sites by AWI’s Cathy Liss. Charles M. Jabbour Mary Lee Jensvold, Ph.D. Photo by Cathy Liss Cathy Liss 4 Michele Walter OFFICERS Cathy Liss, President Cynthia Wilson, Vice President Brutal BLM Roundups Charles M. Jabbour, CPA, Treasurer John Gleiber, Secretary THE UNNECESSARY REMOVAL OF WILD HORSES has reached an alarming rate SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE under the current administration. Thousands of horses have been and continue to Gerard Bertrand, Ph.D. be removed from their native range, and placed in short- and long-term holding Roger Fouts, Ph.D. facilities in the Roger Payne, Ph.D. Midwest. Taxpayers 10 22 Samuel Peacock, M.D. Hope Ryden pay tens of millions Robert Schmidt of dollars a year to John Walsh, M.D. -

Guinea Pigs 79 Group Housing of Males 79 Proper Diet to Prevent Obesity 81 Straw Bedding 83

Caring DiscussionsHands by the Laboratory Animal Refinement & Enrichment Forum Volume II Edited by Viktor Reinhardt Animal Welfare Institute Animal Welfare Institute 900 Pennsylvania Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20003 www.awionline.org Caring Hands Discussions by the Laboratory Animal Refinement & Enrichment Forum, Volume 2 Edited by Viktor Reinhardt Copyright ©2010 Animal Welfare Institute Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-938414-88-9 LCCN 2010910475 Cover photo: Jakub Hlavaty Design: Ava Rinehart and Cameron Creinin Copy editing: Beth Herman, Cathy Liss, Annie Reinhardt and Dave Tilford All papers used in this publication are Acid Free and Elemental Chlorine Free. They also contain 50% recycled content including 30% post consumer waste. All raw materials originate in forests run according to correct principles in full respect for high environmental, social and economic standards at all stages of production. I am dedicating this book to the innocent animal behind bars who has to endure loneliness, boredom and unnecessary distress. Table of Contents Introduction and Acknowledgements i Chapter 1: Basic Issues 2 Annual Usage of Animals in Biomedical Research 4 Cage Space 10 Inanimate Enrichment 16 Enrichment versus Enhancement 17 Behavioral Problems 22 Mood Swings 24 Radio Music/Talk 29 Construction Noise and Vibration Chapter 2: Refinement and Enrichment for Rodents and Rabbits Environmental Enrichment 34 Institutional Standards 35 Foraging Enrichment 36 Investigators’ Permission 38 Rats 40 Amazing Social Creatures 40 Are