The Power of Sound in Creating Humor: Chaplin – a Pioneer of Audio-Gags and of Sound Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charlie Chaplin, City Lights

Beeth o v en a ca d em ie . c a r l davis Charlie Chaplin, City Lights DESINGEL 17 FEBRUARI 98 Film met live orkest ism. villanella en Filmmuseum Antwerpen BEETHOVEN ACADEMIE . CARL DAVIS Charlie Chaplin, City Lights DESINGEL 17 FEBRUARI 98 Film met live orkest ism. villanella en Filmmuseum Antwerpen Beethoven Academie Charlie Chaplin, City Lights Carl Davis muzikale leiding de zwerver Charles Chaplin het blinde meisje Virginia Cherrill haar grootmoeder Florence Lee de miljonair Harry Myers bokser Hank Mann scheidsrechter Eddie Baker butler Allan Garcia burgemeester/portier Henry Bergman straatveger/inbreker Albert Austin inbreker Joe Van Meter krantenjongens Robert Parrish, Austen Jewell man op lift Tiny Ward assistente in bloemenwinkel Mrs. Hyams flik Harry Ayers vrouw die op sigaar zit Florence Wicks figurant in restaurantscène Jean Harlow boksers Tom Dempsey, Eddie McAuliffe, Willie Keeler, Victor Alexander productie Chaplin - United Artists producent/regie scenario/montage Charles Chaplin fotografie Roland Totheroh cameramannen Mark Marlatt, Gordon Pollock aanvang filmconcert 20.00 uur regie-assistenten Harry Crocker, Henry Bergman, einde 21.30 uur Albert Austin geen pauze art director Charles D. Hall muziek Charles Chaplin foto's programmaboekje © and property of arrangeur Arthur Johnston productieleider Alt Reeves Roy Export Company Establishment teksten programmaboekje Frank Van der Kinderen duur 86 min coördinatie programmaboekje deSingel Engelstalige tussentitels druk programmaboekje Tegendruk kopie Photoplay Productions SYNOPSIS Een zwerver (de 'Tramp') wordt verliefd op een blind bloe- menverkoopstertje en hoopt het geld te vinden voor de ope ratie die haar het zicht moet teruggeven. Hij papt aan met een excentrieke miljonair die in dronken toestand zeer vrij gevig is, maar eenmaal nuchter een hardvochtig mens. -

IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2008 Cineteca Del Comune Di Bologna

XXXVII Mostra Internazionale del Cinema Libero IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2008 Cineteca del Comune di Bologna XXII edizione / 22nd Edition Sabato 28 giugno - Sabato 5 luglio / Saturday 28 June - Saturday 5 July Questa edizione del festival è dedicata a Vittorio Martinelli This festival’s edition is dedicated to Vittorio Martinelli IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2008 Via Azzo Gardino, 65 - tel. 051 219 48 14 - fax 051 219 48 21 - cine- XXII edizione [email protected] Segreteria aperta dalle 9 alle 18 dal 28 giugno al 5 luglio / Secretariat Con il contributo di / With the financial support of: open June 28th - July 5th -from 9 am to 6 pm Comune di Bologna - Settore Cultura e Rapporti con l'Università •Cinema Lumière - Via Azzo Gardino, 65 - tel. 051 219 53 11 Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio in Bologna •Cinema Arlecchino - Via Lame, 57 - tel. 051 52 21 75 Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali - Direzione Generale per il Cinema Modalità di traduzione / Translation services: Regione Emilia-Romagna - Assessorato alla Cultura Tutti i film delle serate in Piazza Maggiore e le proiezioni presso il Programma MEDIA+ dell’Unione Europea Cinema Arlecchino hanno sottotitoli elettronici in italiano e inglese Tutte le proiezioni e gli incontri presso il Cinema Lumière sono tradot- Con la collaborazione di / In association with: ti in simultanea in italiano e inglese Fondazione Teatro Comunale di Bologna All evening screenings in Piazza Maggiore, as well as screenings at the L’Immagine Ritrovata Cinema Arlecchino, will be translated into Italian -

Chaplin Film Series

/' \9ti\ * ' * / ; MUSEUM OF MODERN ART MEW YORK 19 ?? WEST 53rd STREET TElEPHONEt CIRCLE 5-8900 CABLES, MODERNART, NEW.YORK For release* Tuesday, Seetesfeer £^, 19^7 So. 96 IARLY C1TAPIX? FILMS AS «Ua3UM 0? MCBSHI? AHS ffet MUSSMSJI of Modern Art, 11 Nta* 53 Street, will, present three vaakg of the. early fi&BS of Charles Chaylia, October 5 - £3* Tvrenty-five film vill too sbcnm in 6 seai-veefcly program* Beginning with selected Keystone ecrasdles of 191k, mads before 12M tossy charaetarisation ves entirely evelred, the ffiogrsas proceed through the transitional Ksaany Fi3ns of 1913 to the couplets eerier of Mutual WlsWj 1916 - lrf# in vhich Chaplin achieved full mastery of hi 3 Bedim* Included vill be Chaplin's first filsa, Uaklaa a llvinflj in vhich fas sppeari in a frock coat, high silk hat, walrus Buutaah* and monocle; his first classic, ffha Treapj and the celebrated r^yGtreet, Asjsasj featured players are Fatty Arbtte&a» Kibel Wmnismlj Ben. furs-ist* Idas Purviaaoei siin Bunaarville end the Koystoae Cops. Music for the series will bo arranged and played by Arthur Kleiner. £here vill be t^o showings dailyj at 3 end 3*30. Malsftlon to the Haseua, 75 cents for adults icd 2!) eeats for cMiSroa incier 16, ineluae.3 the fil-is. A ccaplete schedule is attached* For additional infornation please contact Herbert Broasteinj Assistant Publicity ilreotor, Museum of raflem Art, 11 Vest 53 Street, K. Y. CI-3-8200. THE EARLY FILMS OF CHARLES CHAPLIN presented at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 W, 53 Street, New York, N. -

Exe Pages DP/Mtanglais 25/04/03 15:59 Page 1

exe_pages DP/MTanglais 25/04/03 15:59 Page 1 SELECTION OFFICIELLE • FESTIVAL DE CANNES 2003 • CLÔTURE MARIN KARMITZ présente / presents Un film de / a film by CHARLES CHAPLIN USA / 1936 / 87 mn / 1.33/ mono / Visa : 16.028 DISTRIBUTION MK2 55, rue traversière 75012 Paris Tél : 33 (0)1 44 67 30 80 / Fax : 33 (0)1 43 44 20 18 PRESSE MONICA DONATI Tél : 33 (0)1 43 07 55 22 / Fax: 33 (0)1 43 07 17 97 / Mob: 33 (0)6 85 52 72 97 e-mail: [email protected] VENTES INTERNATIONALES MK2 55, rue traversière 75012 Paris Tél : 33 (0)1 43 07 55 22 / Fax: 33 (0)1 43 07 17 97 AU FESTIVAL DE CANNES RÉSIDENCE DU GRAND HOTEL 47, BD DE LA CROISETTE 06400 CANNES Tél : 33 (0)4 93 38 48 95 SORTIE FRANCE LE 04 JUIN 2003 EN DVD LE 12 JUIN 2003 exe_pages DP/MTanglais 25/04/03 15:59 Page 2 Synopsis The Tramp works on the production line in a gigantic factory. Day after day, he tightens screws. He is very soon alienated by the working conditions and finds himself first in the hospital, then in prison. Once outside, he becomes friends with a runaway orphan girl who the police are searching for. The tramp and the girl join forces to face life's hardships together... exe_pages DP/MTanglais 25/04/03 15:59 Page 4 1931 - Chaplin leaves Hollywood for an 18-month tour of the world. He The Historical Context meets Gandhi and Einstein, and travels widely in Europe. -

Chaplin Shorts

Chaplin Shorts 20 Newly-restored films showcasing the evolution of “the little tramp” 1914-1917 Now Available on DCP Presented by Flicker Alley, LLC THE MAKING OF A LEGEND 12 Chaplin Mutual films and 8 Keystones are available on DCP from Flicker Alley. Chaplin’s maturation as an artist is seen in these films, many of which are considered his best works. In the Keystone comedies, we see the birth of the Tramp. In the Mutuals, we see Chaplin further explor and develop his celebrated Little Tramp character that would soon join Falstaff and Don Quixote in the pantheon of immortal comic characters. His inventiveness shines as he stretches himself to take on new characters. In addition to playing his ‘Little Tramp’ character, he portrays a fireman, a police officer, a prisoner, and more. These shorts make an excellent program on their own or as a companion piece to the screening of a full-length film. [email protected] (323) 851-1905 HIGHLY-ACCLAIMED RELEASES Named one of “The Best “Watching Chaplin's Mutual DVDs and Blu-rays of 2014.” Comedies is a revelation because - Michael Atkinson, BFI’s one can witness a master Sight & Sound magazine filmmaker coming of age.” - Susan King, Los Angeles Times “The transfers of these films are among the most “Gorgeous presentations of stunningly clear I’ve seen the most breathtakingly of films from this era.” stunt-filled and funny - Jef Burnham, pictures from what some Film Monthly consider Charlie Chaplin's most free-wheelingly creative period; from The “These new digital reissues of Immigrant to The Rink and Chaplin’s Mutual films aren’t just beyond, these movies are labors of love. -

Charlot Soldat, De Charles Chaplin

1 CHARLOT SOLDAT, DE CHARLES CHAPLIN Fiche technique * Titre : Charlot Soldat * Titre original : Shoulder Arms * Réalisation : Charles Chaplin * Scénario : Charles Chaplin * Production : Charles Chaplin * Musique : Charles Chaplin * Photographie : Roland Totheroh * Montage : Charles Chaplin * Décors : Charles D. Hall * Pays d'origine : États-Unis * Format : Noir et blanc - 1,33:1 - Film muet - 35 mm * Genre : Comédie * Durée : 46 minutes * Dates de sortie : 20 octobre 1918 (États-Unis), 20 avril 1919 (France) Distribution * Charles Chaplin : 13e matricule * Edna Purviance : La fille française * Sydney Chaplin : Le Kaiser, le sergent * Jack Wilson : Le "Kronprinz" * Henry Bergman : Gros sergent allemand, barman américain, officier allemand * Albert Austin : Soldat américain, soldat allemand et chauffeur du Kaiser * Tom Wilson : Sergent du camp d'entraînement * John Rand : Soldat américain * J. Parks Jones : Soldat américain * Loyal Underwood: Petit officier allemand Synopsis Dans un camp militaire, de nouvelles recrues s'entraînent avant de partir à la guerre en France. L'entraînement est épuisant pour Charlot. Aussitôt l'exercice fini, il s'endort. Une fois arrivé dans les tranchées, il doit s'accommoder de l'insalubrité et du mal du pays, tandis que les obus pleuvent et que les batailles font rage… 2 Sur le réalisateur Charles Spencer Chaplin naît le 16 avril 1889 dans un quartier pauvre de londres. Son père et sa mère sont tous deux chanteurs de variétés. En 1912, il s’établit aux Etats-Unis, où il commence une nouvelle carrière dans le cinéma. En 1914, Charles Chaplin invente le plus célèbre des vagabonds : Charlot. Le public est conquis. Si le vie professionnelle de Charlie Chaplin est un succès, il n’en va pas de même avec sa vie privée : il va de mariages en divorces. -

Artistry in Motion

Artistry in Motion Charlie Chaplin’s Comedies in Historical Perspective Lecturer: PD Dr. Stefan L. Brandt, Guest Professor Winter term 2011/12 Charlie Chaplin – Select Filmography (in chronological order) Making A Living. Dir. Henry Lehrman. Perf. Charles Chaplin, Virginia Kirtley and Alice Davenport. Keystone Film Company, 1914. Kid Auto Races at Venice. Dir. Henry Lehrman. Perf. Charles Chaplin and Henry Lehrman. Keystone Film Company, 1914. The Tramp. Dir. Charlie Chaplin. Perf. Charlie Chaplin, Edna Purviance, Lloyd Bacon. Essanay Studios, 1915. The Immigrant. Dir. Charles Chaplin. Perf. Charles Chaplin, Edna Purviance, Eric Campbell. Mutual Film, 1917. A Dog’s Life. Dir. Charles Chaplin. Perf. Charles Chaplin, Edna Purviance, Dave Anderson. First National Pictures, 1918. The Kid. Dir. Charles Chaplin. Perf. Charles Chaplin, Edna Purviance, Jackie Coogan, Carl Miller. First National Pictures, 1921. Safety Last. Dir. Fred C. Newmeyer and sam Taylor. Perf. Harold Lloyd, Mildred Davis, Bill Strother, Noah Young. Hal Roach Studios, 1923. The Gold Rush. Dir. Charles Chaplin. Perf. Charles Chaplin, Mack Swain, Tom Murray, Henry Bergman. United Artists, 1925. The Circus. Dir. Charles Chaplin. Perf. Charles Chaplin, Merna Kennedy, Al Ernest Garcia, Harry Crocker. United Artists, 1928. City Lights. Dir. Charles Chaplin. Perf. Charles Chaplin, Virginia Cherrill, Florence Lee, Harry Myers. United Artists, 1931. Modern Times. Dir. Charles Chaplin. Perf. Charles Chaplin, Paulette Goddard, Herny Bergman. , 1936. The Great Dictator. Dir. Charles Chaplin. Perf. Charles Chaplin, Paulette Goddard, Jack Oakie, Reginald Gardiner, Billy Gilbert. United Artists, 1940. Monsieur Verdoux. Dir. Charles Chaplin. Perf. Charles Chaplin, Mady Correll, Allison Roddan, Robert Lewis. United Artists, 1947. A King in New York. -

The Gold Rush (United Artists Pressbook, 1925)

This book outlines poblicit)’, advertising and exploitation matter that will enable any exhibitor, in any sb^ city, to put this Charlie Chaplin feature over to big box-office results. There are many news¬ paper stories, one, two and three column advertising cuts, one, two and three column scene cuts for newspaper use, reproductions of the litho¬ graph posters, the lobby display cards and slides, and the music cue sheet. Exhibitor’s Campaign Book FOR CHARLIE CHAPLIN IN » “The Gold Rush” A DRAMATIC COMEDY Written and Directed by Charlie Chaplin c Released by United Artists Corporation Nationwide Song, Record and Radio Tie-up For Charlie Chaplin's **The Gold Rush" Biggest Thing ever put up for Exhibitors Perfect exploitation of a film means the impression of an indelible record of that film on the minds of every film-goer in the country. What Music Tie-up Means By a concerted arrangement with two of the widest mediums of pub¬ Every exhibitor should study in detail the account of the lic approach, United Artists Corporation has obtained for Charlie Chap¬ lin’s new feature comedy, “The Gold Rush” a national exploitation tie-up music exploitation tie-up on “The Gold Rush,” Charlie Chaplin’s which every exhibitor in the country can turn to direct local benefit, with greatest film comedy, consisting of two song numbers written by tremenodus box-office stimulation resulting. Chaplin to be issued in sheet form and on phonograph records. Songs and Records It is the most wide-reaching scheme for public contact ever It is a tie-up with two of the largest song publishing houses and a arranged. -

New Multimedia

Zimmerman Library July-Dec 2017 New Multimedia Michael Mosley, James Wong. "[This] is the NON-FICTION VIDEOS scientific story of your next meal. Dr. Michael Mosley and botanist James Wong celebrate the physics, chemistry, and biology hidden inside Birth of a movement: the battle against every bite."--Container. DVD 363.192 FOO America's first blockbuster, The birth of a nation. [Widescreen format]. [Arlington, Va.]: The talk: race in America. [Widescreen format]. PBS Distribution, 2017. Narrator, Danny Glover. [Arlington, Va.]: PBS Distribution, [2017]. "A ... "In 1915, African American newspaper editor film about "the talk' that parents have with their and civil rights activist William Monroe Trotter children of color, primarily boys, to teach them waged a battle against D.W. Griffith's how to act around the police in order to remain notoriously Ku Klux Klan-friendly blockbuster safe"--OCLC. DVD 363.2 TAL "The Birth of a Nation," which unleashed a fight still raging today about race relations and Kenda, Joe. Homicide hunter. Seasons 1 & representation, and the power and influence of 2. [Silver Spring, Maryland]: Discovery Hollywood. [This production] features Communications, Limited Liability Company, commentary from Spike Lee, Reginald Hudlin, 2015. Disc 1. Into thin air -- Six feet under -- A Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and DJ Spooky and killer always rings twice -- Everybody lies -- numerous clips from the technically Secret life. Disc 2. Chance encounter -- I now groundbreaking but racially astounding epic"-- pronounce you dead -- A gathering of evil -- Last Container. DVD 305.8 BIR call for murder. Disc 3. The spy who killed me -- Slaughterhouse six -- Drive thru murder -- The living weapon. -

Theorizing Film Acting

ROUTLEDGE ADVANCES IN FILM STUDIES Theorizing Film Acting Edited by Aaron Taylor Theorizing Film Acting Routledge Advances in Film Studies 1 Nation and Identity in the New 8 The Politics of Loss and Trauma German Cinema in Contemporary Israeli Cinema Homeless at Home Raz Yosef Inga Scharf 9 Neoliberalism and Global 2 Lesbianism, Cinema, Space Cinema The Sexual Life of Apartments Capital, Culture, and Marxist Lee Wallace Critique Edited by Jyotsna Kapur and 3 Post-War Italian Cinema Keith B. Wagner American Intervention, Vatican Interests 10 Korea’s Occupied Cinemas, Daniela Treveri Gennari 1893-1948 The Untold History of the Film 4 Latsploitation, Exploitation Industry Cinemas, and Latin America Brian Yecies with Ae-Gyung Shim Edited by Victoria Ruétalo and Dolores Tierney 11 Transnational Asian Identities in Pan-Paci c Cinemas 5 Cinematic Emotion in Horror The Reel Asian Exchange Films and Thrillers Edited by Philippa Gates & Lisa The Aesthetic Paradox of Funnell Pleasurable Fear Julian Hanich 12 Narratives of Gendered Dissent in South Asian Cinemas 6 Cinema, Memory, Modernity Alka Kurian The Representation of Memory from the Art Film to Transnational 13 Hollywood Melodrama and the Cinema New Deal Russell J.A. Kilbourn Public Daydreams Anna Siomopoulos 7 Distributing Silent Film Serials Local Practices, Changing Forms, 14 Theorizing Film Acting Cultural Transformation Edited by Aaron Taylor Rudmer Canjels Theorizing Film Acting Edited by Aaron Taylor NEW YORK LONDON First published 2012 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2012 Taylor & Francis The right of Aaron Taylor to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

DISTINGUISHED Residentsof

DISTINGUISHED RESI D ENTS of Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary HILLSIDE HILLSIDE ,%'!#)%3 ,%'!#)%3 1 D ISTINGUISHED RESI D ENTS OF H ILLSI D E ME M O R IAL PA R K AN D MO R TUA R Y 2008 DISTINGUISHED RESIDENTS IR VING AA R ONSON (1895 – 1963) EVE R LASTING PEACE Irving Aaronson’s career began at the age of 11 as a movie theater pianist. In the 1920’s he became a Big Band leader with the Versatile Sextette DISTINGUISHED RESI D ENTS GUI D E : A LEGACY OF LEGEN D S and Irving Aaronson & the Commanders. The Commanders recorded “I’ll Get By,” Cole Porter’s “Let’s Misbehave,” “All By Ourselves in the Moonlight,” “Don’t Look at Me That Way” and “Hi-Ho the Merrio.” Irving Aaronson His band included members Gene Krupa, Claude Thornhill and Artie Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary has provided a place to Shaw. He later worked for MGM as a music coordinator for “Arrivederci Roma” (1957), “This Could Be the Night” (1957), “Meet Me in Las Vegas” honor the accomplishments and legacies of the Jewish community (1956) and as music advisor for “The Merry Widow” (1952). since 1942. We have made it our mission to provide southern ROSLYN ALFIN –SLATE R (1916 – 2002) GA rd EN OF SA R AH California with a memorial park and mortuary dedicated to Dr. Roslyn Alfin-Slater was a highly esteemed UCLA professor and nutrition expert. Her early work honoring loved ones in a manner that is fitting and appropriate. included studies on the relationship between cholesterol and essential fatty acid metabolism. -

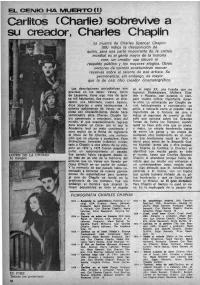

Carlitos (Charlie) Sobrevive a Su Creador, Charles Chaplin

EL GENIO HA MUERTO (I) Carlitos (Charlie) sobrevive a su creador, Charles Chaplin La muerte de Charles Spencer Chaplin (88) indica la desaparición de quien, para una parte importante de la crítica mundial es el genio mayor de la historia cine, un creador que obtuvo el respaldo público y los mayores elogios. Otros sectores de opinión acostumbran marcar reservas sobre el talento de ese artista. Su permanencia, sin embargo, es mayor que la de casi otro creador cinematográfico. Las descripciones periodísticas son en el siglo XX, una hazaña que no precisas en los datos: Vevey, cerca lograron Shakespeare, Moliere, Eins- de Lausanne, tiene algo más de quin tein o Picasso, con quienes lo com ce mil habitantes, dos museos, un cine- paró mucha crítica importante duran teatro, una biblioteca, cuatro bancos, te años. La admiración por Chaplin de doce joyerías y siete restaurantes. A rivó habitualmente a considerarlo un catorce quilómetros de Vevey, se tro genio, a indicarlo como el creador más pieza con Chatel-St-Denis, donde hace importante de la historia del cine e veinticuatro años Charles Chaplin ha indujo al equívoco de creerlo un filó bía comenzado a envejecer, lejos del sofo que opinaba sobre los Grandes mundo, al que ocasionalmente regresó Temas de Todos los Tiempos, cuando para aceptar un Oscar con el que la quizá no haya sido más que un poeta, Academia lavó su mala conciencia y o mejor, un simple hombrecito capaz para recibir de la Reina de Inglaterra de sentir las penas y las ansias de el título de Sir Charles, una nomina cualquier otro hombrecito en el mun ción que no alcanza a cualquiera.