Jordan's Path to Water Security Lies Through Political Reforms And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cooperating for a More Competitive, Innovative, Inclusive and Sustainable Mediterranean

COOPERATING FOR A MORE COMPETITIVE, INNOVATIVE, INCLUSIVE AND SUSTAINABLE MEDITERRANEAN Catalogue of the standard projects funded by the ENI CBC ’Mediterranean Sea Basin’ Programme 1 Publisher Managing Authority Regione Autonoma della Sardegna Cagliari, Italy Concept and editing ENI CBC Med Programme Artwork and graphics Begoña Machancoses, Laura Ojeda Printed November 2019 Disclaimer This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Un- ion. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the Managing Authority of the ENI CBC Med Programme and can under no circumstanc- es be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information in this publica- tion, the ENI CBC Med Programme cannot be held responsible for any information from external sources, technical inaccuracies, ty- pographical errors or other errors herein. Information and links may have changed without notice. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged. COOPERATING FOR A MORE COMPETITIVE, INNOVATIVE, INCLUSIVE AND SUSTAINABLE MEDITERRANEAN Catalogue of the standard projects funded by the ENI CBC ’Mediterranean Sea Basin’ Programme 3 3. SOCIAL INCLUSION AND FIGHT AGAINST POVERTY 48 3.1 Employability of young people (NEETS) and women 50-55 • HELIOS - enHancing thE sociaL Inclusion Of neetS ....................................................................................................................................... 50 ABOUT THE ENI CBC MED PROGRAMME -

PKF Jordan and Iraq PKF Progroup PKF Khattab & Co

PKF Jordan and Iraq PKF ProGroup PKF Khattab & Co. PKF Planning Tax Advisory PKF Human Resource Consulting Market Overview | Aqaba - Jordan September 2015 PKF Jordan and PKF Iraq are member firms of the PKF International Limited network of legally independent firms and do not accept any responsibility or liability for the actions or inactions on the part of any other individual member firm or firms. Country Overview The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has a very strategic location in the heart of the Middle East. It is bounded by Syria from the north, Iraq from the east, Saudi Arabia from the south and southern east and West Bank from the west. Jordan overlooks the Dead Sea from the west and Gulf of Aqaba from south which gives the country a 27 km coastline with the Red Sea. Jordan is a small country with a total area of 89,556 square kilometers. According to the Jordanian Department of Statistics, Jordan’s population reached 6,675,000 in 2014. Jordan had a rising population growth rate of more than 2.2% in 2014. The capital Amman is the biggest city in the country with an estimated population of 2,584,600 in the metropolitan area, therefore forming 38.7% of the country’s population in 2014. Jordan has a vibrant young population, 37.1 percent of the population are less than 14 years old (males form 1,279,370/females form 1,212,090), 59.4 percent are between ages 15 and 64 years (males form 2,052,560/females form 1,915,510) and 3.2 percent are above 65 years (males form 109,070/females form 106,400). -

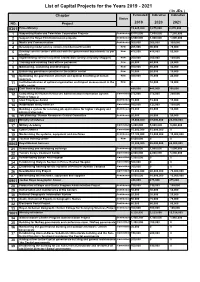

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2019 2020 2021 0301 Prime Ministry 13,625,000 9,875,000 8,870,000 1 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 8,515,000 7,650,000 7,250,000 2 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 3 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 4 Developing model service centers (middle/nourth/south) New 205,000 90,000 70,000 5 Develop service centers affiliated with the government departments as per New 475,000 415,000 50,000 priorities 6 Implementing service recipients satisfaction surveys (mystery shopper) New 200,000 200,000 100,000 7 Training and enabling front offices personnel New 20,000 40,000 20,000 8 Maintaining, sustaining and developing New 100,000 80,000 40,000 9 Enhancing governance practice in the publuc sector New 10,000 20,000 10,000 10 Optimizing the government structure and optimal benefiting of human New 300,000 70,000 20,000 resources 11 Institutionalization of optimal organization and impact measurement in the New 0 10,000 10,000 public sector 0601 Civil Service Bureau 485,000 445,000 395,000 12 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Committed 275,000 275,000 250,000 Project/ Stage 2 13 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 14 Automation and E-services Committed 160,000 125,000 100,000 15 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 15,000 10,000 10,000 administrative jobs. -

Jordan Middle East DISCUSSION PAPER and North Africa Transition Fund September 2017 Middle East and North Africa Transition Fund

Towards a new partnership between government and youth in Jordan Middle East DISCUSSION PAPER and North Africa Transition Fund September 2017 Middle East and North Africa Transition Fund ABOUT THE OECD MENA TRANSITION FUND OF THE DEAUVILLE PARTNERSHIP The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an international body that promotes In May 2011, the Deauville Partnership was launched as a policies to improve the economic and social well-being long-term global initiative that provides Arab countries in of people around the world. It is made up of 35 member transition with a framework based on technical support countries, a secretariat in Paris, and a committee, drawn to strengthen governance for transparent, accountable from experts from government and other fields, for each governments and to provide an economic framework for work area covered by the organisation. The OECD provides sustainable and inclusive growth. a forum in which governments can work together to share experiences and seek solutions to common problems. We The Deauville Partnership has committed to support collaborate with governments to understand what drives Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen and the economic, social and environmental change. We measure Transition Fund is one of the levers to implement this productivity and global flows of trade and investment. commitment. The Transition Fund demonstrates a joint commitment by G7 members, Gulf and regional partners, For more information, please visit www.oecd.org. and international and regional financial institutions to support the efforts of the people and governments of the Partnership countries as they overhaul their economic systems to promote more accountable governance, broad- based, sustainable growth, and greater employment opportunities for youth and women. -

Amman, Jordan

MINISTRY OF WATER AND IRRIGATION WATER YEAR BOOK “Our Water situation forms a strategic challenge that cannot be ignored.” His Majesty Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein “I assure you that the young people of my generation do not lack the will to take action. On the contrary, they are the most aware of the challenges facing their homelands.” His Royal Highness Hussein bin Abdullah Imprint Water Yearbook Hydrological year 2016-2017 Amman, June 2018 Publisher Ministry of Water and Irrigation Water Authority of Jordan P.O. Box 2412-5012 Laboratories & Quality Affairs Amman 1118 Jordan P.O. Box 2412 T: +962 6 5652265 / +962 6 5652267 Amman 11183 Jordan F: +962 6 5652287 T: +962 6 5864361/2 I: www.mwi.gov.jo F: +962 6 5825275 I: www.waj.gov.jo Photos © Water Authority of Jordan – Labs & Quality Affairs © Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources Authors Thair Almomani, Safa’a Al Shraydeh, Hilda Shakhatreh, Razan Alroud, Ali Brezat, Adel Obayat, Ala’a Atyeh, Mohammad Almasri, Amani Alta’ani, Hiyam Sa’aydeh, Rania Shaaban, Refaat Bani Khalaf, Lama Saleh, Feda Massadeh, Samah Al-Salhi, Rebecca Bahls, Mohammed Alhyari, Mathias Toll, Klaus Holzner The Water Yearbook is available online through the web portal of the Ministry of Water and Irrigation. http://www.mwi.gov.jo Imprint This publication was developed within the German – Jordanian technical cooperation project “Groundwater Resources Management” funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) Implemented by: Foreword It is highly evident and well known that water resources in Jordan are very scarce. -

Fact Sheet Expansion of North Aqaba Wastewater Treatment Plant

FACT SHEET EXPANSION OF NORTH AQABA WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANT 2018-2022 • $30 million • Partners: CDM International Inc., Ministry of Water and Irrigation, Water Authority of Jordan, Aqaba Water Company, Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority. BACKGROUND Jordan is one of the most water-scarce countries in the world. A rapidly growing population and changing climate strain the already shrinking water supply. Jordan’s water systems provide comprehensive service coverage throughout the Kingdom, but water supplies are not always constant. Aging infrastructure results in significant water loss. Jordan requires expansions and upgrades to water treatment plants, sewer systems, and wastewater treatment plants in order to cope with the growing demand for diminishing groundwater resources. To support Jordan in . addressing its extreme water scarcity, USAID provides architectural and engineering services to water supply projects, sewer collection systems, and wastewater treatment plants increasing drinking water availability and improving sanitation for millions of Jordanians. In partnership with the Government of Jordan, USAID will continue its six decades of work to expand water infrastructure and strengthen the country’s water sector. NTERNATIONAL INC I CDM PROJECT OVERVIEW : The Expansion and Rehabilitation of North Aqaba Wastewater treatment plant will accommodate the sanitation needs of Aqaba’s growing population and enhance sanitation for residents of Aqaba Governorate. Through this Project, USAID helps to construct new facilities and rehabilitate the existing wastewater treatment plant. The Project will increase the treatment capacity of the plant CREDITPHOTO from 12,000m3/day to 40,000m3/day. 1 USAID.GOV JANUARY 2021 | NOTEWORTHY ACHIEVEMENTS ● Designed and constructed a new plant with a capacity for an average daily flow of 28,000m³/day. -

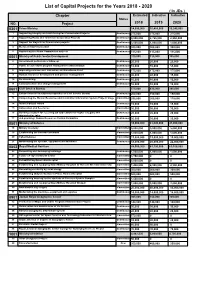

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2018 2019 2020 0301 Prime Ministry 14,090,000 10,455,000 10,240,000 1 Supporting Integrity and Anti-Corruption Commission Projects Continuous 275,000 275,000 275,000 2 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 9,900,000 8,765,000 8,550,000 3 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 4 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 5 Supporting the Media Commission projects Continuous 115,000 115,000 115,000 0501 Ministry of Public Sector Development 310,000 310,000 305,000 6 Government performance follow up Continuous 20,000 20,000 20,000 7 Public sector reform program management administration Continuous 55,000 55,000 55,000 8 Improving services and Innovation and Excellence Fund Continuous 175,000 175,000 175,000 9 Human resources development and policies management Continuous 40,000 40,000 35,000 10 Re-structuring Continuous 10,000 10,000 10,000 11 Communication and change management Continuous 10,000 10,000 10,000 0601 Civil Service Bureau 575,000 435,000 345,000 12 Enhancement of institutional capacities of Civil Service Bureau Continuous 200,000 150,000 150,000 13 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Project/ Stage Committed 290,000 200,000 110,000 2 14 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 15 Automation and E-services Committed 30,000 30,000 30,000 16 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 20,000 20,000 20,000 administrative jobs. -

THE STARTUP GUIDE Business in Jordan

Your complete guide to registering and licensing a small THE STARTUP GUIDE business in Jordan Find out what to do, where to go and what fees are required to formalize your small business in this simple, step-by-step guide Contents WHY SHOULD I REGISTER AND LICENSE MY BUSINESS? ........................................................................................ 2 WHAT ARE THE STEPS I NEED TO TAKE IN ORDER TO FORMALIZE MY BUSINESS? ............................................... 3 HOW DO I KNOW WHAT TYPE OF BUSINESS TO REGISTER? ................................................................................. 4 HOW DO I CHOOSE A BUSINESS STRUCTURE THAT’S RIGHT FOR ME? ................................................................. 6 I’VE CHOSEN MY BUSINESS STRUCTURE… WHAT NEXT? ...................................................................................... 8 I’VE GOTTEN MY PRE-APPROVALS. HOW DO I REGISTER MY BUSINESS? ............................................................. 9 A) REGISTERING AN INDIVIDUAL ESTABLISHMENT ........................................................................................ 10 B) REGISTERING A GENERAL PARTNERSHIP OR LIMITED PARTNERSHIP COMPANY ...................................... 13 C) REGISTERING A LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY ........................................................................................... 16 D) REGISTERING A PRIVATE SHAREHOLDING COMPANY................................................................................ 20 I’VE REGISTERED MY BUSINESS. HOW CAN I SET -

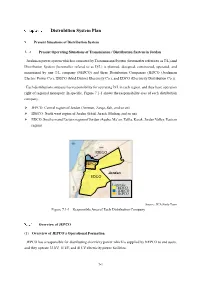

Distrubition System Plan

Distrubition System Plan Present Situations of Distribution System Present Operating Situations of Transmission / Distribution System in Jordan Jordanian power system which is consisted by Transmission System (hereinafter refered to as T/L) and Distribution System (hereinafter refered to as D/L) is planned, designed, constructed, operated, and maintained by one T/L company (NEPCO) and three Distribution Companies (JEPCO (Jordanian Electric Power Co.), IDECO (Irbid District Electricity Co.), and EDCO (Electricity Distribution Co.)). Each distribution company has responsibility for operating D/L in each region, and they have operation right of regional monopoly. In specific, Figure 7.1-1 shows the responsibility area of each distribution company. JEPCO: Central region of Jordan (Amman, Zarqa, Salt, and so on) IDECO: North west region of Jordan (Irbid, Jarash, Mufraq, and so on) EDCO: Southern and Eastern region of Jordan (Aqaba, Ma’an, Tafila, Karak, Jordan Valley, Eastern region) IDECO JEPCO Jordan EDCO Legends: ■:EDCO ■:IDECO ■:JEPCO Source: JICA Study Team Figure 7.1-1 Responsible Area of Each Distribution Company Overview of JEPCO (1) Overview of JEPCO’s Operational Formation JEPCO has a responsible for distributing electricity power which is supplied by NEPCO to end users, and they operate 33 kV, 11 kV, and 415 V electricity power facilities. 7-1 Headquarters of JEPCO is located in Amman, and they operate the distribution facilities from secondary side bus of each BSP to terminals of end user. Organization chart of JEPCO is shown in Figure 7.1-2. JEPCO buys the electricity power from NEPCO, and the boundary point of trading is secondary side of BSP. -

Environmental and Social Assessment Disi-Mudawarra to Amman Water Conveyance System

MINISTRY OF WATER & IRRIGATION Environmental and Social Assessment Disi-Mudawarra to Amman Water Conveyance System Main Report – Part C: Project Specific Environmental & Social Assessment Volume 1 of 2 June 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT DISI-MUDAWARRA TO AMMAN WATER CONVEYANCE SYSTEM TABLE OF CONTENTS ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT REPORT Page COVERING LETTER TABLE OF CONTENTS i LIST OF ANNEXES vii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ix Executive Summary S-1 Main Report – Part A: Overview 1 INTRODUCTION A-1 1.1 Background A-1 1.2 Project Objectives A-2 1.3 Organization of the ESA Study A-2 1.4 Description of Parts A, B and C of the ESA Study A-4 1.5 Relationship between Parts A, B and C of the ESA Study A-6 1.6 Consultations during the ESA Study A-6 1.7 ESA Disclosure A-8 1.8 Maps to Support Environmental and Social Management Plan A-8 2 LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK A-10 2.1 Introduction A-10 2.2 Institutional Framework A-11 2.2.1 Overview of Governmental Organizations A-11 2.2.2 Universities and Research Institutes A-21 2.2.3 Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) A-22 2.3 Major Stakeholders A-24 2.4 Applicable National Environmental Legislation A-24 2.4.1 Laws A-25 2.4.2 Regulations (By-laws) A-32 2.4.3 Strategies A-36 2.4.4 Related Environmental International and Regional Conventions and Treaties A-38 2.5 Applicable Policies of the World Bank A-41 2.6 Legal and Institutional Issues A-44 2.7 Recommendations A-46 3 PROPOSED PROJECT A-47 3.1 Origin and Scope A-47 3.2 Location A-48 3.3 Major Elements A-50 Final -

Disaster Risk Management Profile for Aqaba Special Economic Zone

Disaster Risk Management Profile for Aqaba Special Economic Zone Project: Support to Building National Capacity for Earthquake Risk Reduction at ASEZA in Jordan May, 2010 “We are determined to make Aqaba Special Economic Zone (ASEZ) a successful project and bring in more investment to the area.” King Abdulla II, Monday, 23 Aug 2004. Contents Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 Demographic, economic, social and cultural characteristics 1.2 Governance style 1.3 National hazardscape 1.4 National disaster management structure and relevant legislation 1.5 National land use management system and relevant legislations 1.6 Significance of the Aqaba Special Economic Zone to the nation 1.7 Geographical Setting of the Aqaba Special Economic Zone Chapter 2: Inter-City Linkages 2.1 Internal division of the Aqaba Special Economic Zone 2.2 Governance/management style of the Aqaba Special Economic Zone 2.3 Formal Arrangements 2.4 Relevant Legislations/Regulations Chapter 3: Land Use Management 3.1 Relevant Legislations 3.2 Responsible agents and their relationship 3.3 Effectiveness of current arrangements (German Report) Chapter 4: Vulnerability Issues 4.1 Seismicity of the region 4.2 Faulting systems 4.3 Ground motions 4.4 Seismic Zonation 4.5 Site Geology and Soil characteristics 4.6 At-Risk Groups 4.7 At-Risk Locations 4.8 Non-engineering Dwellings 4.9 Aqaba Special Economic Zone Policies on Vulnerability Alleviation Chapter 5: Disaster Risk Management Arrangement 5.1 Functional arrangements 5.2 Risk Assessment 5.3 Risk Communication Chapter 6: Disaster Risk Management Vision Chapter 7: Sound Practices (SP) Chapter 8: Issues List of Tables Table 1: Major disasters in Jordan over the past 100 years. -

Executive Summary State Party

Executive Summary State Party Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan State, Province, Region Aqaba Special Economic Zone Name of the Nominated Property Wadi Rum Protected Area Geographic Coordinates to the Nearest Second Central Management Station: N 29 38 22.60 E 35 26 02.32 Textual Description of the Boundary of the Nominated Area The Wadi Rum Protected Area is located in the southern part of Jordan and lies within the Aqaba Special Economic Zone which is part of the greater Aqaba Governorate, about 310 km south of Amman and about 60 km north east of the coastal city of Aqaba. It covers an area of 74,200 ha (seventy four thousand and two hundred hectares), out of which, 73,300 ha (seventy three thousand and three hundred hectares) are being nominated for world heritage status as mixed site for natural and cultural outstanding universal values. Wadi Rum Protected Area represents the largest protected area in Jordan and the Levant region, and covers almost one percent of the total surface area of the country. Wadi Rum Protected Area forms a major part of the Hisma desert of southern Jordan and northern Arabia, lying to the east of the Jordan Rift Valley and south of the steep escarpment of the central Jordanian plateau. The borders of the Protected Area extend from Qaa' Disi in the North-East to Jabal Al Fara’a in the South-East and to Wadi Sweibit in the South-West. 6 World Heritage Nominated Area – General Map, Topography 7 World Heritage Nominated Area – General Map 8 World Heritage Nominated Area – Map with Buffer Zone 9 Justification – Statement of Outstanding Universal Value The Wadi Rum Protected Area is a mixed property composed of scenically stunning and tightly interwoven natural and cultural attributes in a lived-in desert environment.